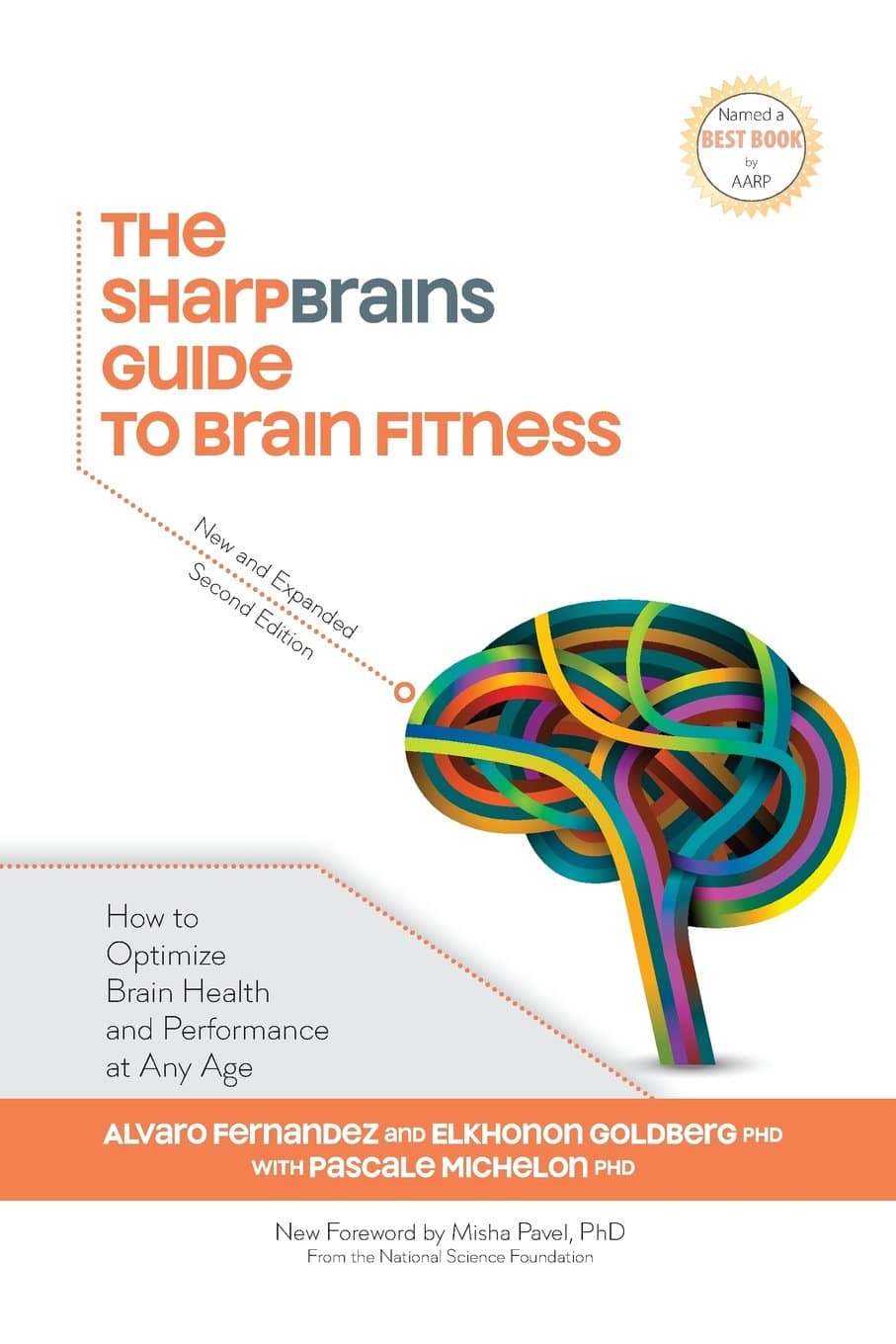

The SharpBrains Guide to Brain Fitness – by Alvaro Fernandez et al.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We say “et al.” in the by-line, because this one has a flock of authors, including Dr. Pascale Michelon, Dr. Sandra Bond Chapman, Dr. Elkehon Goldberg, and various others if we include the foreword, introduction, etc.

This is relevant, because those who contributed to the meat of the book (i.e., those listed above), it makes the work a lot more scientifically reliable; one skilled science writer might make a mistake; it’s much less likely to make it through to publication when there are a bevy of doctors in the mix, each staking their reputation on the book’s content, and thus having a vested interest in checking each other’s work as well as their own.

As for what this multidisciplinary team have to offer? The book covers such things as:

- how the brain works (especially the possibilities of neuroplasticity), and what that means for such things as memory and attention

- being “a coach not a patient”; i.e., being active rather than passive in one’s approach to brain health

- the relevance of physical exercise, how much, and what kind

- the relevance (and limitations) of diet choices for brain health

- the relevance of such things as learning new languages and musical training

- the relevance of social engagement, and how some (but not all) social engagement can boost cognition

- methods for managing stress and building resilience to same (critical for maintaining a healthy brain)

- “cross-fit for your brain”, that is to say, a multi-vector collection of tools to explore, ranging from meditation to CBT to biofeedback and more.

The style is pop-science without being sensationalist, just communicating ideas clearly, with enough padding to feel casual, and not like a dense read. Importantly, it’s also practical and applicable too, which is something we always look for here.

Bottom line: if you’d like to be given a good overview of what things work (and how much they can be expected to work), along with a good framework to put that knowledge into practice, then this is a great book for you.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Parent Effectiveness Training – by Dr. Thomas Gordon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Do you want your home (or workplace, for that matter) to be a place of peace? This book literally got the author nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. Can’t really get much higher praise than that.

The title is “Parent Effectiveness Training”, but in reality, the advice in the book is applicable to all manner of relationships, including:

- romantic relationships

- friends

- colleagues

- …and really any human interaction.

It covers some of the same topics we did today (and more) in much more detail than we ever could in a newsletter. It lays out formulae to use, gives plenty of examples, and/but is free from undue padding.

- Pros: this isn’t one of those “should have been an article” books. It has so much valuable content.

- Cons: It is from the 1970s* so examples may feel “dated” now.

In addition to going into much more detail on some of the topics covered in today’s issue of 10almonds, Dr. Gordon also talks in-depth about the concept of “problem-ownership”.

In a nutshell, that means: whose problem is a given thing? Who “has” what problem? Everyone needs to be on the same page about everyone else’s problems in the situation… as well as their own, which is not always a given!

Dr. Gordon presents, in short, tools not just to resolve conflict, but also to pre-empt it entirely. With these techniques, we can identify and deal with problems (together!) well before they arise.

Everybody wins.

Get your copy of “Parent Effectiveness Training” from Amazon today!

*Note: There is an updated edition on the market, and that’s what you’ll find upon following the above link. This reviewer (hi!) has a battered old paperback from the 1970s and cannot speak for what was changed in the new edition. However: if the 70s one is worth more than its weight in gold (and it is), the new edition is surely just as good, if not better!

Share This Post

-

Lies I Taught in Medical School – by Dr. Robert Lufkin

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There seems to be a pattern of doctors who practice medicine one way, get a serious disease personally, and then completely change their practice of medicine afterwards. This is one of those cases.

Dr. Lufkin here presents, on a chapter-by-chapter basis, the titularly promised “lies” or, in more legally compliant speak (as he acknowledges in his preface), flawed hypotheses that are generally taught as truths. In many cases, the “lie” is some manner of “xyz is normal and nothing to worry about”, and/or “there is nothing to be done about xyz; suck it up”.

The end result of the information is not complicated—enjoy a plants-forward whole foods low-carb diet to avoid metabolic diseases and all the other things to branch off from same (Dr. Lufkin makes a fair case for metabolic disease leading to a lot of secondary diseases that aren’t considered metabolic diseases per se). But, the journey there is actually important, as it answers a lot of questions that are much less commonly understood, and often not even especially talked-about, despite their great import and how they may affect health decisions beyond the dietary. Things like understanding the downsides of statins, or the statistical models that can be used to skew studies, per relative risk reduction and so forth.

Bottom line: this book gives the ins and outs of what can go right or wrong with metabolic health and why, and how to make sure you don’t sabotage your health through missing information.

Click here to check out Lies I Taught In Medical School, and arm yourself with knowledge!

Share This Post

-

Applesauce vs Cranberry Sauce – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing applesauce to cranberry sauce, we picked the applesauce.

Why?

It mostly comes down to the fact that apples are sweeter than cranberries:

In terms of macros, they are both equal on fiber (both languishing at a paltry 1.1g/100g), and/but cranberry sauce has 4x the carbs, of which, more than 3x the sugar. Simply, cranberry sauce recipes invariably have a lot of added sugar, while applesauce recipes don’t need that. So this is a huge relative win for applesauce (we say “relative” because it’s still not great, but cranberry sauce is far worse).

In the category of vitamins, applesauce has more of vitamins B1, B2, B5, B6, B9, and C, while cranberry sauce has more of vitamins E, K, and choline. A more moderate win for applesauce this time.

When it comes to minerals, applesauce has more calcium, copper, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium, while cranberry sauce has more iron, manganese, and selenium. Another moderate win for applesauce.

Since we’ve discussed relative amounts rather than actual quantities, it’s worth noting that neither sauce is a good source of vitamins or minerals, and neither are close to just eating the actual fruits. Just, cranberry sauce is the relatively more barren of the two.

While cranberries famously have some UTI-fighting properties, you cannot usefully gain this benefit from a sauce that (with its very high sugar content and minimal fiber) actively feeds the very C. albicans you are likely trying to kill.

All in all, a pitiful show of nutritional inadequacy from these two products today, but one is relatively less bad than the other, and that’s the applesauce.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Good Health From Head To Toe

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

This newsletter has been growing a lot lately, and so have the questions/requests, and we love that! In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

Q: I am now in the “aging” population. A great concern for me is Alzheimers. My father had it and I am so worried. What is the latest research on prevention?

Very important stuff! We wrote about this not long back:

- See: How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

- See also: Brain Food? The Eyes Have It!

(one good thing to note is that while Alzheimer’s has a genetic component, it doesn’t appear to be hereditary per se. Still, good to be on top of these things, and it’s never too early to start with preventive measures!)

Q: Foods that help build stronger bones and cut inflammation? Thank you!

We’ve got you…

For stronger bones / To cut inflammation

That “stronger bones” article is about the benefits of collagen supplementation for bones, but there’s definitely more to say on the topic of stronger bones, so we’ll do a main feature on it sometime soon!

Q: Veganism, staying mentally sharp, best exercises for weight gain?

All great stuff! Let’s do a run-down:

- Veganism? As a health and productivity newsletter, we’ll only be focusing veganism’s health considerations, but it does crop up from time to time! For example:

- Which Plant Milk? (entirely about such)

- Plant vs Animal Protein (mostly about such)

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later) (discusses one benefit of such)

- Staying mentally sharp? You might like the things-against-dementia pieces we linked to in the previous response!

- It’s also worth noting that some kinds of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s, can begin the neurodegenerative process 20 years before symptoms show, and can be influenced by lifestyle choices 20 years before that, so it’s definitely never too early be on top of these things!

- Best exercises for weight gain? We’ll do a main feature one of these days (filled with good science and evidence), but in few words meanwhile: core exercises, large muscle groups, heavy weights, few reps, build up slowly. Squats are King.

Q: I am interested in the following: Aging, Exercise, Diet, Relationships, Purpose, Lowering Stress

You’re going to love our Psychology Sunday editions of 10almonds! You might like some of these…

- Relationships: Seriously Useful Communication Skills!

- Purpose: Are You Flourishing? (There’s a Scale)

- Managing stress: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

- Also about managing stress: Sunday Stress-Buster

- Also applicable to stress: How To Set Your Anxiety Aside

Q: I’d like to know more about type 2 diabetic foot problems

You probably know that the “foot problems” thing has less to do with the feet and more to do with blood and nerves. So, why the feet?

The reason feet often get something like the worst of it, is because they are extremities, and in the case of blood sugars being too high for too long too often, they’re getting more damage as blood has to fight its way back up your body. Diabetic neuropathy happens when nerves are malnourished because the blood that should be keeping them healthy, is instead syrupy and sluggish.

We’ll definitely do a main feature sometime soon on keeping blood sugars healthy, for both types of diabetes plus pre-diabetes and just general advice for all.

In the meantime, here’s some very good advice on keeping your feet healthy in the context of diabetes. This one’s focussed on Type 1 Diabetes, but the advice goes for both:

! Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why You Can’t Skimp On Amino Acids

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our body requires 20 amino acids (the building blocks of protein), 9 of which it can’t synthesize (thus called: “essential”) and absolutely must get from food. Normally, we get these amino acids from protein in our diet, and we can also supplement them by taking amino acid supplements if we wish.

Specifically, we require (per kg of bodyweight) a daily average of:

- Histidine: 10 mg

- Isoleucine: 20 mg

- Leucine: 39 mg

- Lysine: 30 mg

- Methionine: 10.4 mg

- Phenylalanine*: 25 mg

- Threonine: 15 mg

- Tryptophan: 4 mg

- Valine: 26 mg

*combined with the non-essential amino acid tyrosine

Source: Protein and Amino Acid Requirements In Human Nutrition: WHO Technical Report

Why this matters

A lot of attention is given to protein, and making sure we get enough of it, especially as we get older, because the risk of sarcopenia (muscle mass loss) increases with age:

However, not every protein comes with a complete set of essential amino acids, and/or have only trace amounts of of some amino acids, meaning that a dietary deficiency can arrive if one’s diet is too restrictive.

And, if we become deficient in even just one amino acid, then bad things start to happen quite soon. We only have so much space, so we’re going to oversimplify here, but:

- Histidine: is needed to produce histamine (vital for immune responses, amongst other things), and is also important for maintaining the myelin sheaths on nerve cells.

- Isoleucine: is very involved in muscle metabolism and makes up the bulk of muscle tissue.

- Leucine: is critical for muscle synthesis and repair, as well as wound healing in general, and blood sugar regulation.

- Lysine: is also critical in muscle synthesis, as well as calcium absorption and hormone production, as well as making collagen.

- Methionine: is very important for energy metabolism, zinc absorption, and detoxification.

- Phenylalanine: is a necessary building block of a lot of neurotransmitters, as well as being a building block of some amino acids not listed here (i.e., the ones your body synthesizes, but can’t without phenylalanine).

- Threonine: is mostly about collagen and elastin production, and is also very important for your joints, as well as fat metabolism.

- Tryptophan: is the body’s primary precursor to serotonin, so good luck making the latter without the former.

- Valine: is mostly about muscle growth and regeneration.

So there you see, the ill effects of deficiency can range from “muscle atrophy” to “brain stops working” and “bones fall apart” and more. In short, any essential amino acid deficiency not remedied will ultimately result in death; we literally become non-viable as organisms without these 9 things.

What to do about it (the “life hack” part)

Firstly, if you eat a lot of animal products, those are “complete” proteins, meaning that they contain all 9 essential amino acids in sensible quantities. The reason that all animal products have these, is because they are just as essential for the other animals as they are for us, so they, just like us, must consume (and thus contain) them.

However, a lot of animal products come with other health risks:

Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy? ← this covers which animal products are definitely very health-risky, and which are probably fine according to current best science

…so many people may prefer to get more (or possibly all) dietary protein from plants.

However, plants, unlike us, do not need to consume all 9 essential amino acids, and this may or may not contain them all.

Soy is famously a “complete” protein insofar as it has all the amino acids we need.

But what if you’re allergic to soy?

Good news! Peas are also a “complete” protein and will do the job just fine. They’re also usually cheaper.

Final note

An oft-forgotten thing is that some other amino acids are “conditionally essential”, meaning that while we can technically synthesize them, sometimes we can’t synthesize enough and must get them from our diet.

The conditions that trigger this “conditionally essential” status are usually such things as fighting a serious illness, recovering from a serious injury, or pregnancy—basically, things where your body has to work at 110% efficiency if it wants to get through it in one piece, and that extra 10% has to come from somewhere outside the body.

Examples of commonly conditionally essential amino acids are arginine and glycine.

Arginine is critical for a lot of cell-signalling processes as well as mitochondrial function, as well as being a precursor to other amino acids, including creatine.

As for glycine?

Check out: The Sweet Truth About Glycine

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

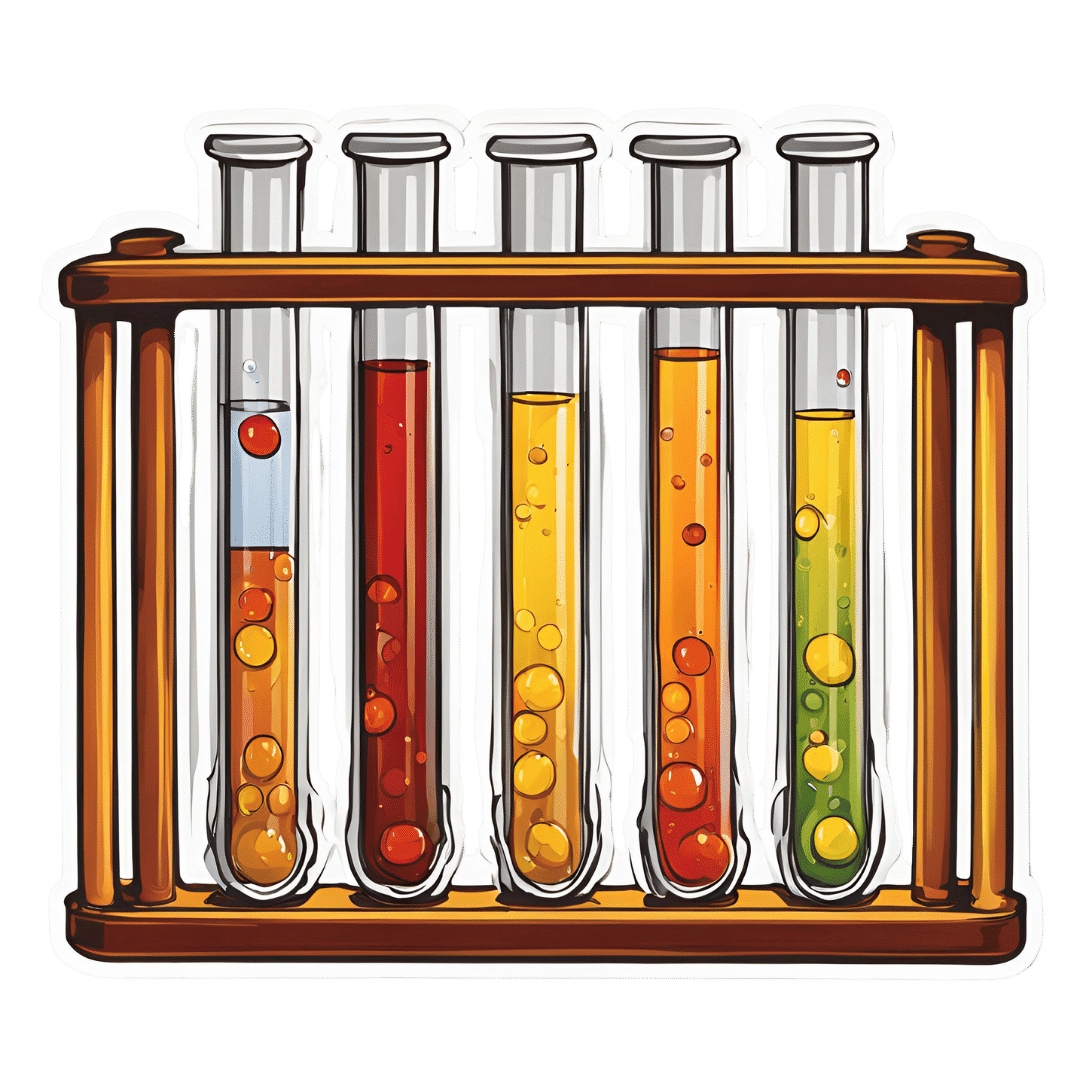

12 Things Your Urine Says About Your Health (Test At Home)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Urine has been used to assess health since Ancient Egypt (fun fact: because of Egyptian language having multiple sounds that get transliterated to “a” in English, the condition of passing blood in one’s urine was known as “Aaaaa” ← this word has three syllables; “Aa-a-aa”).

Modern techniques are more advanced than those of times past (for example, diabetes is no longer diagnosed by a urine taste-test), but basic urine inspection is still a very useful indicator of many things. Recognizing changes in urine can even help detect life-threatening conditions early:

Traffic lights?

How urine works: water that we consume is absorbed into the bloodstream and filtered by the kidneys. Urine is essentially blood with actual the blood cells filtered out and/or broken down. The yellow color comes from urochrome, produced during red blood cell breakdown. Here’s how things can happen a little differently:

- Fluorescent yellow: caused by excess vitamin B2 from supplements; harmless.

- Red urine: can indicate blood (bladder cancer, UTIs), hemoglobin, or myoglobin; seek medical attention.

- Dark brown/tea-colored urine: may result from muscle damage or blood cell destruction; requires evaluation.

- Orange urine: caused by dehydration, medications, or liver/bile duct issues (if paired with pale stools).

- Purple urine: UTI bacteria produce pigments that can cause this; treatable with antibiotics.

- Green urine: rare; caused by medications or dyes like methylene blue.

- Frothy/foamy urine: indicates high protein levels, often from kidney damage (e.g. per diabetes and/or hypertension).

- Crystal-clear urine: suggests overhydration, which can dangerously lower sodium levels.

- Dark yellow/amber urine: may mean dehydration; drink more water to maintain a light yellow color.

- Not peeing enough: may indicate severe dehydration or kidney failure; urgent medical attention needed.

- Peeing too much: often linked to diabetes or excessive water intake; can lead to dehydration or low sodium.

- Color-changing urine: port wine color signals porphyria; black urine indicates alkaptonuria (oxidation of homogentisic acid). Both are serious.

Bonus: if you eat a lot of beetroot and then your urine is pink/red/purple, that’s probably just the pigments passing through. If it persists though, then of course, see above.

For more on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Why You Don’t Need 8 Glasses Of Water Per Day

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: