5 Steps To Quit Sugar Easily

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sugar is one of the least healthy things that most people consume, yet because it’s so prevalent, it can also be tricky to avoid at first, and the cravings can also be a challenge. So, how to quit it?

Step by step

Dr. Mike Hansen recommends the following steps:

- Be aware: a lot of sugar consumption is without realizing it or thinking about it, because of how common it is for there to be added sugar in things we might purchase ready-made, even supposedly healthy things like yogurts, or easy-to-disregard things like condiments.

- Recognize sugar addiction: a controversial topic, but Dr. Hansen comes down squarely on the side of “yes, it’s an addiction”. He wants us to understand more about the mechanics of how this happens, and what it does to us.

- Reduce gradually: instead of going “cold turkey”, he recommends we avoid withdrawal symptoms by first cutting back on liquid sugars like sodas, juices, and syrups, before eliminating solid sugar-heavy things like candy, sugar cookies, etc, and finally the more insidious “why did they put sugar in this?” added-sugar products.

- Find healthy alternatives: simple like-for-like substitutions; whole fruits instead of juices/smoothies, for example. 10almonds tip: stuffing dates with an almond each makes it very much like eating chocolate, experientially!

- Manage cravings: Dr. Hansen recommends distraction, and focusing on upping other healthy habits such as hydration, exercise, and getting more vegetables.

For more on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

- Mythbusting The Not-So-Sweet Science Of Sugar Addiction

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Would a Second Trump Presidency Look Like for Health Care?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

On the presidential campaign trail, former President Donald Trump is, once again, promising to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act — a nebulous goal that became one of his administration’s splashiest policy failures.

“We’re going to fight for much better health care than Obamacare. Obamacare is a catastrophe,” Trump said at a campaign stop in Iowa on Jan. 6.

The perplexing revival of one of Trump’s most politically damaging crusades comes at a time when the Obama-era health law is even more popular and widely used than it was in 2017, when Trump and congressional Republicans proved unable to pass their own plan to replace it. That failed effort was a big part of why Republicans lost control of the House of Representatives in the 2018 midterms.

Despite repeated promises, Trump never presented his own Obamacare replacement. And much of what Trump’s administration actually accomplished in health care has been reversed by the Biden administration.

Still, Trump secured some significant policy changes that remain in place today, including efforts to bring more transparency to prices charged by hospitals and paid by health insurers.

Trying to predict Trump’s priorities in a second term is even more difficult given that he frequently changes his positions on issues, sometimes multiple times.

The Trump campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Perhaps Trump’s biggest achievement is something he rarely talks about on the campaign trail. His administration’s “Operation Warp Speed” managed to create, test, and bring to market a covid-19 vaccine in less than a year, far faster than even the most optimistic predictions.

Many of Trump’s supporters, though, don’t support — and some even vehemently oppose — covid vaccines.

Here is a recap of Trump’s health care record:

Public Health

Trump’s pandemic response dominates his overall record on health care.

More than 400,000 Americans died from covid over Trump’s last year in office. His travel bans and other efforts to prevent the global spread of the virus were ineffective, his administration was slower than other countries’ governments to develop a diagnostic test, and he publicly clashed with his own government’s health officials over the response.

Ahead of the 2020 election, Trump resumed large rallies and other public campaign events that many public health experts regarded as reckless in the face of a highly contagious, deadly virus. He personally flouted public health guidance after contracting covid himself and ending up hospitalized.

At the same time, despite what many saw as a politicization of public health by the White House, Trump signed a massive covid relief bill (after first threatening to veto it). He also presided over some of the largest boosts for the National Institutes of Health’s budget since the turn of the century. And the mRNA-based vaccines Operation Warp Speed helped develop were an astounding scientific breakthrough credited with helping save millions of lives while laying the groundwork for future shots to fight other diseases including cancer.

Abortion

Trump’s biggest contribution to abortion policy was indirect: He appointed three Supreme Court justices, who were instrumental in overturning the constitutional right to an abortion.

During his 2024 campaign, Trump has been all over the place on the red-hot issue. Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, Trump has bemoaned the issue as politically bad for Republicans; criticized one of his rivals, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for signing a six-week abortion ban; and vowed to broker a compromise with “both sides” on abortion, promising that “for the first time in 52 years, you’ll have an issue that we can put behind us.”

He has so far avoided spelling out how he’d do that, or whether he’d support a national abortion ban after any number of weeks.

More recently, however, Trump appears to have mended fences over his criticism of Florida’s six-week ban and more with key abortion opponents, whose support helped him get elected in 2016 — and whom he repaid with a long list of policy changes during his presidency.

Among the anti-abortion actions taken by the Trump administration were a reinstatement of the “Mexico City Policy” that bars giving federal funds to international organizations that support abortion rights; a regulation to bar Planned Parenthood and other organizations that provide abortions from the federal family planning program, Title X; regulatory changes designed to make it easier for health care providers and employers to decline to participate in activities that violate their religious and moral beliefs; and other changes that made it harder for NIH scientists to conduct research using fetal tissue from elective abortions.

All of those policies have since been overturned by the Biden administration.

Health Insurance

Unlike Trump’s policies on reproductive health, many of his administration’s moves related to health insurance still stand.

For example, in 2020, Trump signed into law the No Surprises Act, a bipartisan measure aimed at protecting patients from unexpected medical bills stemming from payment disputes between health care providers and insurers. The bill was included in the $900 billion covid relief package he opposed before signing, though Trump had expressed support for ending surprise medical bills.

His administration also pushed — over the vehement objections of health industry officials — price transparency regulations that require hospitals to post prices and insurers to provide estimated costs for procedures. Those requirements also remain in place, although hospitals in particular have been slow to comply.

Medicaid

While first-time candidate Trump vowed not to cut popular entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, his administration did not stick to that promise. The Affordable Care Act repeal legislation Trump supported in 2017 would have imposed major cuts to Medicaid, and his Department of Health and Human Services later encouraged states to require Medicaid recipients to prove they work in order to receive health insurance.

Drug Prices

One of the issues the Trump administration was most active on was reducing the price of prescription drugs for consumers — a top priority for both Democratic and Republican voters. But many of those proposals were blocked by the courts.

One Trump-era plan that never took effect would have pegged the price of some expensive drugs covered by Medicare to prices in other countries. Another would have required drug companies to include prices in their television advertisements.

A regulation allowing states to import cheaper drugs from Canada did take effect, in November 2020. However, it took until January 2024 for the FDA, under Trump’s successor, to approve the first importation plan, from Florida. Canada has said it won’t allow exports that risk causing drug shortages in that country, leaving unclear whether the policy is workable.

Trump also signed into law measures allowing pharmacists to disclose to patients when the cash price of a drug is lower than the cost using their insurance. Previously pharmacists could be barred from doing so under their contracts with insurers and pharmacy benefit managers.

Veterans’ Health

Trump is credited by some advocates for overhauling Department of Veterans Affairs health care. However, while he did sign a major bill allowing veterans to obtain care outside VA facilities, White House officials also tried to scuttle passage of the spending needed to pay for the initiative.

Medical Freedom

Trump scored a big win for the libertarian wing of the Republican Party when he signed into law the “Right to Try Act,” intended to make it easier for patients with terminal diseases to access drugs or treatments not yet approved by the FDA.

But it is not clear how many patients have managed to obtain treatment using the law because it is aimed at the FDA, which has traditionally granted requests for “compassionate use” of not-yet-approved drugs anyway. The stumbling block, which the law does not address, is getting drug companies to release doses of medicines that are still being tested and may be in short supply.

Trump said in a Jan. 10 Fox News town hall that the law had “saved thousands and thousands” of lives. There’s no evidence for the claim.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

-

Sun-dried Tomatoes vs Black Olives – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing sun-dried tomatoes to black olives, we picked the sun-dried tomatoes.

Why?

These common snack-salad items may seem similar in consistency, but their macros are very different: the tomatoes, being dried, have proportionally a lot more protein, carbs, and fiber. The olives, meanwhile, have more fat (and/but yes, a very healthy blend of fats). Note that these comments are true for the things themselves; be aware that sun-dried tomatoes are often sold in vegetable oil, which would obviously change the macros considerably and be much less healthy. So, for the sake of statistics, we’re assuming you got sun-dried tomatoes that aren’t soaked in oil. All in all, we’re calling this category a win for the tomatoes, but those fats from the olives are very good too.

In terms of vitamins, the sun-dried tomatoes being dried again means that the loss of water weight means the vitamin content is proportionally much higher; the tomatoes are higher in vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, and K, while olives are higher only in vitamin E (but in their defence, olives have 165x more vitamin E than sun-dried tomatoes). Still, a win for sun-dried tomatoes here.

When it comes to minerals, it’s a similar story for the same reason; the loss of water weight in the sun-dried tomatoes makes them much more nutritionally dense; they are higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while the olives are higher only in sodium. Note, we’re looking at black olives today; green olives would be even higher in sodium than black ones, as they are “cured” for longer.

Lastly, in terms of polyphenols, they both have a lot of great things to bring, but sun-dried tomatoes are pretty much the richest natural source of lycopene, which itself a very powerful polyphenol even my general polyphenol standards, so we’d call this one a win for the sun-dried tomatoes too.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Brain-Gut Highway: A Two-Way Street

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Brain-Gut Two-Way Highway

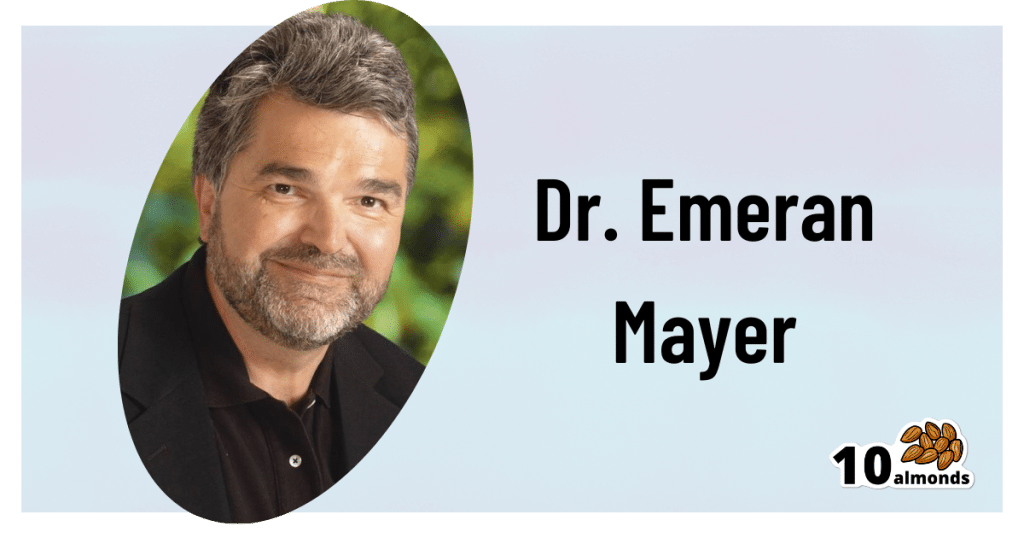

This is Dr. Emeran Mayer. He has the rather niche dual specialty of being a gastroenterologist and a neurologist. He has published over 353 peer reviewed scientific articles, and he’s a professor in the Departments of Medicine, Physiology, and Psychiatry at UCLA. Much of his work has been pioneering medical research into gut-brain interactions.

We know the brain and gut are connected. What else does he want us to know?

First, that it is a two-way interaction. It’s about 90% “gut tells the brain things”, but it’s also 10% “brain tells the gut things”, and that 10% can make more like a 20% difference, if for example we look at the swing between “brain using that 10% communication to tell gut to do things worse” or “brain using that 10% communication to tell gut to do things better”, vs the midpoint null hypothesis of “what the gut would be doing with no direction from the brain”.

For example, if we are experiencing unmanaged chronic stress, that is going to tell our gut to do things that had an evolutionary advantage 20,000–200,000 years ago. Those things will not help us now. We do not need cortisol highs and adrenal dumping because we ate a piece of bread while stressed.

Read more (by Dr. Mayer): The Stress That Evolution Has Not Prepared Us For

With this in mind, if we want to look after our gut, then we can start before we even put anything in our mouths. Dr. Mayer recommends managing stress, anxiety, and depression from the head downwards as well as from the gut upwards.

Here’s what we at 10almonds have written previously on how to manage those things:

- No-Frills, Evidence-Based Mindfulness

- How To Set Anxiety Aside

- The Mental Health First-Aid You’ll Hopefully Never Need

Do eat for gut health! Yes, even if…

Unsurprisingly, Dr. Mayer advocates for a gut-friendly, anti-inflammatory diet. We’ve written about these things before:

…but there’s just one problem:

For some people, such as with IBS, Crohn’s, and colitis, the Mediterranean diet that we (10almonds and Dr. Mayer) generally advocate for, is inaccessible. If you (if you have those conditions) eat as we describe, a combination of the fiber in many vegetables and the FODMAPs* in many fruits, will give you a very bad time indeed.

*Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Monosaccharides And Polyols

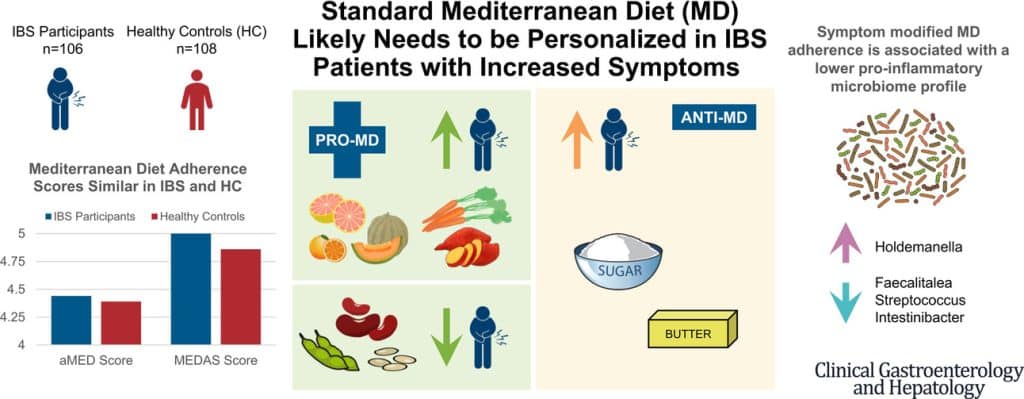

Dr. Mayer has the answer to this riddle, and he’s not just guessing; he and his team did science to it. In a study with hundreds of participants, he measured what happened with adherence (or not) to the Mediterranean diet (or modified Mediterranean diet) (or not), in participants with IBS (or not).

The results and conclusions from that study included:

❝Among IBS participants, a higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, sugar, and butter was associated with a greater severity of IBS symptoms. Multivariate analysis identified several Mediterranean Diet foods to be associated with increased IBS symptoms.

A higher adherence to symptom-modified Mediterranean Diet was associated with a lower abundance of potentially harmful Faecalitalea, Streptococcus, and Intestinibacter, and higher abundance of potentially beneficial Holdemanella from the Firmicutes phylum.

A standard Mediterranean Diet was not associated with IBS symptom severity, although certain Mediterranean Diet foods were associated with increased IBS symptoms. Our study suggests that standard Mediterranean Diet may not be suitable for all patients with IBS and likely needs to be personalized in those with increased symptoms.❞

In graphical form:

And if you’d like to read more about this (along with more details on which specific foods to include or exclude to get these results), you can do so…

- The study itself (full article): The Association Between a Mediterranean Diet and Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Dr. Mayer’s blog (lay explanation): The Benefits of a Modified Mediterranean Diet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Want to know more?

Dr. Mayer offers many resources, including a blog, books, recipes, podcasts, and even a YouTube channel:

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Ideal Blood Pressure Numbers Explained

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Maybe I missed it but the study on blood pressure did it say what the 2 numbers should read ideally?❞

We linked it at the top of the article rather than including it inline, as we were short on space (and there was a chart rather than a “these two numbers” quick answer), but we have a little more space today, so:

Category Systolic (mm Hg) Diastolic (mm Hg) Normal < 120 AND < 80 Elevated 120 – 129 AND < 80 Stage 1 – High Blood Pressure 130 – 139 OR 80 – 89 Stage 2 – High Blood Pressure 140 or higher OR 90 or higher Hypertensive Crisis Above 180 AND/OR Above 120 To oversimplify for a “these two numbers” answer, under 120/80 is generally considered good, unless it is under 90/60, in which case that becomes hypotension.

Hypotension, the blood pressure being too low, means your organs may not get enough oxygen and if they don’t, they will start shutting down.

To give you an idea how serious this, this is the closed-circuit equivalent of the hypovolemic shock that occurs when someone is bleeding out onto the floor. Technically, bleeding to death also results in low blood pressure, of course, hence the similarity.

So: just a little under 120/80 is great.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Kiwi vs Grapefruit – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kiwi to grapefruit, we picked the kiwi.

Why?

In terms of macros, kiwi has nearly 2x the protein, slightly more carbs, and 2x the fiber; both fruits are low glycemic index foods, however.

When it comes to vitamins, kiwi has more of vitamins B3, B6, B7, B9, C, E, K, and choline, while grapefruit has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, and B5. An easy win for kiwi.

In the category of minerals, kiwi is higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while grapefruit is not higher in any minerals. So, no surprises for guessing which wins this category.

One thing that grapefruit is a rich source of: furanocoumarin, which can inhibit cytochrome P-450 3A4 isoenzyme and P-glycoptrotein transporters in the intestine and liver—slowing down their drug metabolism capabilities, thus effectively increasing the bioavailability of many drugs manifold.

This may sound superficially like a good thing (improving bioavailability of things we want), but in practice it means that in the case of many drugs, if you take them with (or near in time to) grapefruit or grapefruit juice, then congratulations, you just took an overdose. This happens with a lot of meds for blood pressure, cholesterol (including statins), calcium channel-blockers, anti-depressants, benzo-family drugs, beta-blockers, and more. Oh, and Viagra, too. Which latter might sound funny, but remember, Viagra’s mechanism of action is blood pressure modulation, and that is not something you want to mess around with unduly. So, do check with your pharmacist to know if you’re on any meds that would be affected by grapefruit or grapefruit juice!

All in all, adding up the categories makes for an overwhelming total win for kiwis.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer ← kiwi is top of the list!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Felt Time – by Dr. Marc Wittmann

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book goes far beyond the obvious “time flies when you’re having fun / passes slowly when bored”, or “time seems quicker as we get older”. It does address those topics too, but even in doing so, unravels deeper intricacies within.

The author, a research psychologist, includes plenty of reference to actual hard science here, and even beyond subjective self-reports. For example, you know how time seems to slow down upon immediate apparent threat of violent death (e.g. while crashing, while falling, or other more “violent human” options)? We learn of an experiment conducted in an amusement park, where during a fear-inducing (but actually safe) plummet, subjective time slows down yes, but measures of objective perception and cognition remained the same. So much for adrenal superpowers when it comes to the brain!

We also learn about what we can change, to change our perception of time—in either direction, which is a neat collection of tricks to know.

The style is on the dryer end of pop-sci; we suspect that being translated from German didn’t help its levity. That said, it’s not scientifically dense either (i.e. not a lot of jargon), though it does have many references (which we like to see).

Bottom line: if you’ve ever wished time could go more quickly or more slowly, this book can help with that.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: