Hypertension: Factors Far More Relevant Than Salt

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hypertension: Factors Far More Relevant Than Salt

Firstly, what is high blood pressure vs normal, and what do those blood pressure readings mean?

Rather than take up undue space here, we’ll just quickly link to…

Blood Pressure Readings Explained (With A Colorful Chart)

More details of specifics, at:

Hypotension | Normal | Elevated | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Danger zone

Keeping Blood Pressure Down

As with most health-related things (and in fact, much of life in general), prevention is better than cure.

People usually know “limit salt” and “manage stress”, but there’s a lot more to it!

Salt isn’t as big a factor as you probably think

That doesn’t mean go crazy on the salt, as it can cause a lot of other problems, including organ failure. But it does mean that you can’t skip the salt and assume your blood pressure will take care of itself.

This paper, for example, considers “high” sodium consumption to be more than 5g per day, and urinary excretion under 3g per day is considered to represent a low sodium dietary intake:

Sodium Intake and Hypertension

Meanwhile, health organizations often recommend to keep sodium intake to under 2g or under 1.5g

Top tip: if you replace your table salt with “reduced sodium” salt, this is usually sodium chloride (regular table salt) cut with potassium chloride, which is almost as “salty” tastewise, but obviously contains less sodium. Not only that, but potassium actually helps the body eliminate sodium, too.

The rest of what you eat is important too

The Mediterranean Diet is as great for this as it is for most health conditions.

If you sometimes see the DASH diet mentioned, that stands for “Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension”, and is basically the Mediterranean Diet with a few tweaks.

What are the tweaks?

- Beans went down a bit in priority

- Red meat got removed entirely instead of “limit to a tiny amount”

- Olive oil was deprioritized, and/but vegetable oil is at the bottom of the list (i.e., use sparingly)

You can check out the details here, with an overview and examples:

DASH Eating Plan—Description, Charts, and Recipes

Don’t drink or smoke

And no, a glass of red a day will not help your heart. Alcohol does make us feel relaxed, but that is because of what it does to our brain, not what it does to our heart.

In reality, even a single drink will increase blood pressure. Yes, really:

And smoking? It’s so bad that even second-hand smoke increases blood pressure:

Get those Zs in

Sleep is a commonly underestimated/forgotten part of health, precisely because in a way, we’re not there for it when it happens. We sleep through it! But it is important, including to protect against hypertension:

Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption

Move your body!

Moving your body often is far more important for your heart than running marathons or bench-pressing your spouse.

Those 150 minutes “moderate exercise” (e.g. walking) per week are important, and can be for example:

- 22 minutes per day, 7 days per week

- 25 minutes per day, 6 days per week

- 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week

- 75 minutes per day, 2 days per week

If you’d like to know more about the science and evidence for this, as well as practical suggestions, you can download the complete second edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans here (it’s free, and no sign-up required!)

If you prefer a bite-size summary, then here’s their own:

Top 10 Things to Know About the Second Edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

PS: Want a blood pressure monitor? We don’t sell them (or anything else), but for your convenience, here’s a good one you might want to consider.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

In Crisis, She Went to an Illinois Facility. Two Years Later, She Still Isn’t Able to Leave.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Series: Culture of Cruelty:Inside Illinois’ Mental Health System

State-run facilities in Illinois are supposed to care for people with mental and developmental disabilities. But patients have been subjected to abuse, neglect and staff misconduct for decades, despite calls for change.

Kaleigh Rogers was in crisis when she checked into a state-run institution on Illinois’ northern border two years ago. Rogers, who has cerebral palsy, had a mental health breakdown during the pandemic and was acting aggressively toward herself and others.

Before COVID-19, she had been living in a small group home; she had been taking college classes online and enjoyed going out with friends, volunteering and going to church. But when her aggression escalated, she needed more medical help than her community setting could provide.

With few viable options for intervention, she moved into Kiley Developmental Center in Waukegan, a much larger facility. There, she says she has fewer freedoms and almost nothing to do, and was placed in a unit with six other residents, all of whom are unable to speak. Although the stay was meant to be short term, she’s been there for two years.

The predicament facing Rogers and others like her is proof, advocates say, that the state is failing to live up to the promise it made in a 13-year-old federal consent decree to serve people in the community.

Rogers, 26, said she has lost so much at Kiley: her privacy, her autonomy and her purpose. During dark times, she cries on the phone to her mom, who has reduced the frequency of her visits because it is so upsetting for Rogers when her mom has to leave.

The 220-bed developmental center about an hour north of Chicago is one of seven in the state that have been plagued by allegations of abuse and other staff misconduct. The facilities have been the subject of a monthslong investigation by Capitol News Illinois and ProPublica about the state’s failures to correct poor conditions for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The news organizations uncovered instances of staff who had beaten, choked, thrown, dragged and humiliated residents inside the state-run facilities.

Advocates hoped the state would become less reliant on large institutions like these when they filed a lawsuit in 2005, alleging that Illinois’ failure to adequately fund community living options ended up segregating people with intellectual and developmental disabilities from society by forcing them to live in institutions. The suit claimed Illinois was in direct violation of a 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision in another case, which found that states had to serve people in the most integrated setting of their choosing.

Negotiations resulted in a consent decree, a court-supervised improvement plan. The state agreed to find and fund community placements and services for individuals covered by the consent decree, thousands of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities across Illinois who have put their names on waiting lists to receive them.

Now, the state has asked a judge to consider ending the consent decree, citing significant increases in the number of people receiving community-based services. In a court filing in December, Illinois argued that while its system is “not and never will be perfect,” it is “much more than legally adequate.”

But advocates say the consent decree should not be considered fulfilled as long as people with disabilities continue to live without the services and choices that the state promised.

Across the country, states have significantly downsized or closed their large-scale institutions for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities in favor of smaller, more integrated and more homelike settings.

But in Illinois, a national outlier, such efforts have foundered. Efforts to close state-operated developmental centers have been met with strong opposition from labor unions, the communities where the centers are located, local politicians and some parents.

U.S. District Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman in Chicago is scheduled in late summer to decide whether the state has made enough progress in building up community supports to end the court’s oversight.

For some individuals like Rogers, who are in crisis or have higher medical or behavioral challenges, the state itself acknowledges that it has struggled to serve them in community settings. Rogers said she’d like to send this message on behalf of those in state-operated developmental centers: “Please, please get us out once and for all.”

“Living Inside a Box”

Without a robust system of community-based resources and living arrangements to intervene during a crisis, state-operated developmental centers become a last resort for people with disabilities. But under the consent decree agreement, the state, Equip for Equality argues, is expected to offer sufficient alternative crisis supports to keep people who want them out of these institutions.

In a written response to questions, Rachel Otwell, a spokesperson for the Illinois Department of Human Services, said the state has sought to expand the menu of services it offers people experiencing a crisis, in an effort to keep them from going into institutions. But Andrea Rizor, a lawyer with Equip for Equality, said, “They just don’t have enough to meet the demand.”

For example, the state offers stabilization homes where people can live for 90 days while they receive more intensive support from staff serving the homes, including medication reviews and behavioral interventions. But there are only 32 placements available — only four of them for women — and the beds are always full, Rizor said.

Too many people, she said, enter a state-run institution for short-term treatment and end up stuck there for years for various reasons, including shortcomings with the state’s discharge planning and concerns from providers who may assume those residents to be disruptive or difficult to serve without adequate resources.

That’s what happened to Rogers. Interruptions to her routine and isolation during the pandemic sent her anxiety and aggressive behaviors into overdrive. The staff at her community group home in Machesney Park, unsure of what to do when she acted out, had called the police on several occasions.

Doctors also tried to intervene, but the cocktail of medications she was prescribed turned her into a “zombie,” Rogers said. Stacey Rogers, her mom and legal guardian, said she didn’t know where else to turn for help. Kiley, she said, “was pretty much the last resort for us,” but she never intended for her daughter to be there for this long. She’s helped her daughter apply to dozens of group homes over the past year. A few put her on waitlists; most have turned her down.

“Right now, all she’s doing is living inside a box,” Stacey Rogers said.

Although Rogers gave the news organizations permission to ask about her situation, IDHS declined to comment, citing privacy restrictions. In general, the IDHS spokesperson said that timelines for leaving institutions are “specific to each individual” and their unique preferences, such as where they want to live and speciality services they may require in a group home.

Equip for Equality points to people like Rogers to argue that the consent decree has not been sufficiently fulfilled. She’s one of several hundred in that predicament, the organization said.

“If the state doesn’t have capacity to serve folks in the community, then the time is not right to terminate this consent decree, which requires community capacity,” Rizor said.

Equip for Equality has said that ongoing safety issues in these facilities make it even more important that people covered by the consent decree not be placed in state-run institutions. In an October court brief, citing the news organizations’ reporting, Equip for Equality said that individuals with disabilities who were transferred from community to institutional care in crisis have “died, been raped, and been physically and mentally abused.”

Over the summer, an independent court monitor assigned to provide expert opinions in the consent decree, in a memo to the court, asked a judge to bar the state from admitting those individuals into its institutions.

In its December court filing, the state acknowledged that there are some safety concerns inside its state-run centers, “which the state is diligently working on,” as well as conditions inside privately operated facilities and group homes “that need to be addressed.” But it also argued that conditions inside its facilities are outside the scope of the consent decree. The lawsuit and consent decree specifically aimed to help people who wanted to move out of large private institutions, but plaintiffs’ attorneys argue that the consent decree prohibits the state from using state-run institutions as backup crisis centers.

In arguing to end the consent decree, the state pointed to significant increases in the number of people served since it went into effect. There were about 13,500 people receiving home- and community-based services in 2011 compared with more than 23,000 in 2023, it told the court.

The state also said it has significantly increased funding that is earmarked to pay front-line direct support professionals who assist individuals with daily living needs in the community, such as eating and grooming.

In a statement to reporters, the human services department called these and other improvements to the system “extraordinary.”

Lawyers for the state argued that those improvements are enough to end court oversight.

“The systemic barriers that were in place in 2011 no longer exist,” the state’s court filing said.

Among those who were able to find homes in the community is Stanley Ligas, the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit that led to the consent decree. When it was filed in 2005, he was living in a roughly 100-bed private facility but wanted to move into a community home closer to his sister. The state refused to fund his move.

Today, the 56-year-old lives in Oswego with three roommates in a house they rent. All of them receive services to help their daily living needs through a nonprofit, and Ligas has held jobs in the community: He previously worked in a bowling alley and is now paid to make public appearances to advocate for others with disabilities. He lives near his sister, says he goes on family beach vacations and enjoys watching professional wrestling with friends. During an interview with reporters, Ligas hugged his caregiver and said he’s “very happy” and hopes others can receive the same opportunities he’s been given.

While much of that progress has come only in recent years, under Gov. JB Pritzker’s administration, it has proven to be vulnerable to political and economic changes. After a prolonged budget stalemate, the court in 2017 found Illinois out of compliance with the Ligas consent decree.

At the time, late and insufficient payments from the state had resulted in a staffing crisis inside community group homes, leading to escalating claims of abuse and neglect and failures to provide routine services that residents relied on, such as help getting to work, social engagements and medical appointments in the community. Advocates worry about what could happen under a different administration, or this one, if Illinois’ finances continue to decline as projected.

“I acknowledge the commitments that this administration has made. However, because we had so far to come, we still have far to go,” said Kathy Carmody, chief executive of The Institute on Public Policy for People with Disabilities, which represents providers.

While the wait for services is significantly shorter than it was when the consent decree went into effect in 2011, there are still more than 5,000 adults who have told the state they want community services but have yet to receive them, most of them in a family home. Most people spend about five years waiting to get the services they request. And Illinois continues to rank near the bottom in terms of the investment it makes in community-based services, according to a University of Kansas analysis of states’ spending on services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Advocates who believe the consent decree has not been fulfilled contend that Illinois’ continued reliance on congregate settings has tied up funds that could go into building up more community living options. Each year, Illinois spends about $347,000 per person to care for those in state-run institutions compared with roughly $91,000 per person spent to support those living in the community.

For Rogers, the days inside Kiley are long, tedious and sometimes chaotic. It can be stressful, but Rogers told reporters that she uses soothing self-talk to calm herself when she feels sad or anxious.

“I tell myself: ‘You are doing good. You are doing great. You have people outside of here that care about you and cherish you.’”

This article is republished from ProPublica under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Mineral-Rich Mung Bean Pancakes

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mung beans are rich in an assortment of minerals, especially iron, copper, phosphorus, and magnesium. They’re also full of protein and fiber! What better way to make pancakes healthy?

You will need

- ½ cup dried green mung beans

- ½ cup chopped fresh parsley

- ½ cup chopped fresh dill

- ¼ cup uncooked wholegrain rice

- ¼ cup nutritional yeast

- 1 tsp MSG, or 2 tsp low-sodium salt

- 2 green onions, finely sliced

- 1 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Soak the mung beans and rice together overnight.

2) Drain and rinse, and blend them in a blender with ¼ cup of water, to the consistency of regular pancake batter, adding more water (sparingly) if necessary.

3) Transfer to a bowl and add the rest of the ingredients except for the olive oil, which latter you can now heat in a skillet over a medium-high heat.

4) Add a few spoonfuls of batter to the pan, depending on how big you want the pancakes to be. Cook on both sides until you get a golden-brown crust, and repeat for the rest of the pancakes.

5) Serve! As these are savory pancakes, you might consider serving them with a little salad—tomatoes, olives, and cucumbers go especially well.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

- What’s The Deal With MSG?

- All About Olive Oils: Is “Extra Virgin” Worth It?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Biggest Cause Of Back Pain

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Will Harlow, specialist over-50s physiotherapist, shares the most common cause (and its remedy) in this video:

The seat of the problem

The issue (for most people, anyway) is not in the back itself, nor the core in general, but rather, in the glutes. That is to say: the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus. They assist in bending forwards (collaborating half-and-half with your back muscles), and help control pelvic alignment while walking.

Sitting for long periods weakens the glutes, causing the back to overcompensate, leading to pain. So, obviously don’t do that, if you can help it. Weak glutes shift the work to your back muscles during bending and walking, increasing strain and—as a result—back pain.

The solution (besides “sit less”) is to do specific exercises to strengthen the glutes. When you do, focus on good form and do not try to push through pain. If the exercises themselves all cause pain, then stop and consult a local physiotherapist to figure out your next step.

With that in mind, the five exercises recommended in this video to strengthen glutes and reduce back pain are:

- Hip abduction (isometric): use a heavy resistance band or belt around legs above the knees, push outwards.

- The clam: lie on your side, bend your knees 90°, and lift your top knee while keeping your body forward. Focus on glute engagement.

- Clam with resistance band: use a light resistance band above your knees and perform the same clam exercise.

- Hip abduction (straight leg): lie on your side, keep legs straight, lift your top leg diagonally backward. Lead with your heel to target your glutes and avoid back strain.

- Hip abduction with resistance band: place a resistance band around your ankles, and lift leg as in the previous exercise.

For more on all these, plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- 6 Ways To Look After Your Back

- Strong Curves: A Woman’s Guide To Building A Better Butt And Body – by Bret Contreras & Kellie Davis

- How To Stop Pain From Spreading

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

A Supplement To Rival St. John’s Wort Against Depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Do You Feel The SAMe?

S-Adeonsyl-L-Methionone (SAMe) is a chemical found naturally in the body, and/but enjoyed widely as a supplement. The main reasons people take it are:

- Improve mood (antidepressant effect)

- Improve joints (reduce osteoarthritis symptoms)

- Improve liver (detoxifying effect)

Let’s see what the science says for each of those claims…

Does it improve mood?

It seems to perform comparably to St. John’s Wort (which is good; it performs comparably to Prozac).

Best of all, it does this with fewer contraindications (St. John’s Wort has so many contraindications).

Here’s how they stack up:

This looks very promising, though it’d be nice to see a larger body of research, to be sure.

Does it reduce osteoarthritis symptoms?

The good news: it performs comparably to ibuprofen, with fewer side effects!

The bad news: it also performs comparably to placebo!

Read into that what you will about ibuprofen’s usefulness vs OA symptoms.

Read all about it:

S-Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip

If you were hoping for something for OA or similar symptoms, you might like our previous main features:

- Avoiding/Managing Osteoarthritis

- Managing Chronic Pain (Realistically!)

- The 7 Approaches To Pain Management

- (Science-Based) Alternative Pain Relief

Does it help against liver disease?

According to adverts for SAMe: absolutely!

According to science: we don’t know

The science for this is so weak that it’d be unworthy of mention if it weren’t for the fact that SAMe is so widely sold as good against hepatotoxicity.

To be clear: maybe it really is great! Science hasn’t yet disproved its usefulness either.

It is popularly assumed to be beneficial due to there being an association between lower levels of SAMe in the body (remember, it is also produced inside our bodies) and development of liver disease, especially cholestasis.

Here’s an example of what pretty much every study we found was like (inconclusive research based mostly on mice):

S-adenosylmethionine in liver health, injury, and cancer

For other options for liver health, consider:

Is it safe?

Safety trials have been done ranging from 3 months to 2 years, with no serious side effects coming to light. So, it appears quite safe.

That said, as with anything, there are contraindications, such as:

- if you have bipolar disorder, skip this unless directed by your health care provider, because it may worsen the symptoms of mania

- if you are on SSRIs or other serotonergic drugs, it may interact with those

- if you are immunocompromised, you might want to skip it can increase the risk of P. carinii growth in such cases

As always, do speak with your doctor/pharmacist for personalized advice.

Summary

SAMe’s evidence-based qualities seem to stack up as follows:

- Against depression: good

- Against osteoarthritis: weak

- Against liver disease: unknown

As for safety, it has been found quite safe for most people.

Where can I get it?

We don’t sell it, but here is an example product on Amazon, for your convenience

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Fix Your Upper Back With These Three Steps

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When it comes to back pain, the lower back gets a lot of attention, but what about when it’s nearer the neck and shoulders?

Reaching for better health

In this short video, Liv describes and shows three exercises:

Exercise 1: Thoracic Pullover (Dumbbell Pullover)

Purpose: Improves overhead reach and shoulder mobility.

Equipment: light weight, yoga block, or foam roller.

Steps:- Lie on the floor with the foam roller/block beneath the upper back.

- Hold the weight in both hands, arms extended upward.

- Inhale deeply and reach the weight toward the ceiling.

- Exhale and arc your spine over the block, moving the weight backward.

- Keep core tension to maintain a neutral lower back position.

- Perform 10 repetitions.

Exercise 2: Rotational Mobility Stretch

Purpose: enhances torso rotation, core strength, and hip mobility.

Equipment: none (or a mat)

Steps:- Lie on your side with knees stacked at 90° and arms extended in front.

- Hold a weight in the top hand.

- Inhale and lift the top arm toward the ceiling, extending the shoulder blade.

- Exhale and twist your torso, allowing the arm to move toward the floor.

- Modify by extending the bottom leg for a deeper twist if needed.

- Perform 6 reps per side, switching legs and repeating on the other side.

Exercise 3: Doorway/Pole Side Stretch

Purpose: targets multiple areas for a deep, satisfying stretch.

Equipment: door frame, pole, or wall.

Steps:- Stand at arm’s length from the wall or frame.

- Cross the outer leg (furthest from the wall) behind the inner leg.

- Place the closest hand on the wall and reach the other arm overhead.

- Grip the wall or frame with the top hand, pressing away with the bottom hand.

- Lean into a banana-shaped curve and rotate your chest upward for a deeper stretch.

- Hold for 20–30 seconds per side and repeat 2–3 times.

For more on all of these, plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

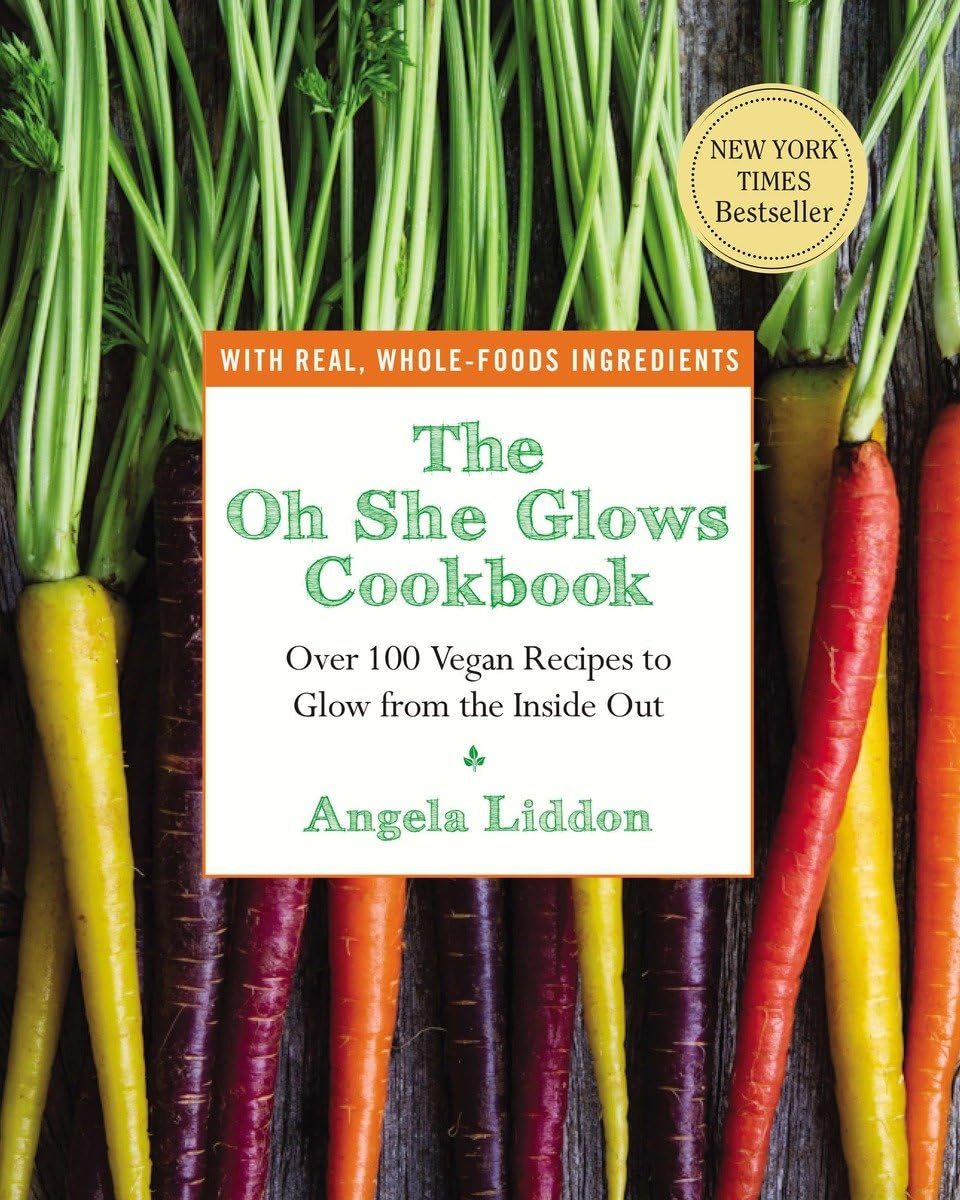

The Oh She Glows Cookbook – by Angela Liddon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Let’s get the criticism out of the way first: notwithstanding the subtitle promising over 100 recipes, there are about 80-odd here, if we discount recipes that are no-brainer things like smoothies, sides such as for example “roasted garlic”, or meta-ingredients such as oat flour (instructions: blend the oats and you get oat flour).

The other criticism is more subjective: if you are like this reviewer, you will want to add more seasonings than recommended to most of the recipes. But that’s easy enough to do.

As for the rest: this is a very healthy cookbook, and quite wide-ranging and versatile, with recipes that are homely, with a lot of emphasis on comfort foods (but still, healthy), though certainly some are perfectly worthy of entertaining too.

A nice bonus of this book is that it offers a lot of available substitutions (much like we do at 10almonds), and also ways of turning the recipe into something else entirely with just a small change. This trait more than makes up for the slight swindle in terms of number of recipes, since some of the recipes have bonus recipes snuck in.

Bottom line: if you’d like to broaden your plant-based cooking range, this book is a fine option for expanding your repertoire.

Click here to check out The Oh She Glows Cookbook, and indeed glow!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: