You Are Not Broken – by Dr. Kelly Casperson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many women express “I think I’m broken down there”, and it turns out simply that neither they nor their partners had the right knowledge, that’s all. The good news is: bedroom competence is an entirely learnable skill!

Dr. Casperson is a urologist, and over the years has expanded her work into all things pelvic, including the relevant use of both systemic and topical hormones (as in, hormones to increase overall blood serum levels of that hormone, like most HRT, and also, creams and lotions to increase levels of a given hormone in one particular place).

However, this is not 200 pages to say “take hormones”. Rather, she covers many areas of female sexual health and wellbeing, including yes, simply pleasure. From the physiological to the psychological, Dr. Casperson talks the reader through avoiding blame games and “getting out of your head and into your body”.

Bottom line: if you (or a loved one) are one of the many women who have doubts about being entirely correctly set up down there, then this book is definitely for you.

Click here to check out You Are Not Broken, and indeed stop “should-ing” all over your sex life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight

This is Dr. Michael Greger. We’ve featured him before: Brain Food? The Eyes Have It!

This time, we’re working from his latest book, the excellent “How Not To Age”, which we reviewed all so recently. It is very information-dense, but we’re going to be focussing on one part, his “anti-aging eight”, that is to say, eight interventions he rates the most highly to slow aging in general (other parts of the book pertained to slowing eleven specific pathways of aging, or preserving specific bodily functions against aging, for example).

Without further ado, his “anti-aging eight” are…

- Nuts

- Greens

- Berries

- Xenohormesis & microRNA manipulation

- Prebiotics & postbiotics

- Caloric restriction / IF

- Protein restriction

- NAD+

As you may have noticed, some of these are things might appear already on your grocery shopping list; others don’t seem so “household”. Let’s break them down:

Nuts, greens, berries

These are amongst the most nutrient-dense and phytochemical-useful parts of the diet that Dr. Greger advocates for in his already-famous “Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen”.

For brevity, we’ll not go into the science of these here, but will advise you: eat a daily portion of nuts, a daily portion of berries, and a couple of daily portions of greens.

Xenohormesis & microRNA manipulation

You might, actually, have these on your grocery shopping list too!

Hormesis, you may recall from previous editions of 10almonds, is about engaging in a small amount of eustress to trigger the body’s self-strengthening response, for example:

Xenohormesis is about getting similar benefits, second-hand.

For example, plants that have been grown to “organic” standards (i.e. without artificial pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers) have had to adapt to their relatively harsher environment by upping their levels of protective polyphenols and other phytochemicals that, as it turns out, are as beneficial to us as they are to the plants:

Hormetic Effects of Phytochemicals on Health and Longevity

Additionally, the flip side of xenohormesis is that some plant compounds can themselves act as a source of hormetic stress that end up bolstering us. For example:

In essence, it’s not just that it has anti-oxidant effect; it also provides a tiny oxidative-stress immunization against serious sources of oxidative stress—and thus, aging.

MicroRNA manipulation is, alas, too complex to truly summarize an entire chapter in a line or two, but it has to do with genetic information from the food that we eat having a beneficial or deleterious effect to our own health:

Diet-derived microRNAs: unicorn or silver bullet?

A couple of quick takeaways (out of very many) from Dr. Greger’s chapter on this is to spring for the better quality olive oil, and skip the cow’s milk:

- Impact of Phenol-Enriched Virgin Olive Oils on the Postprandial Levels of Circulating microRNAs Related to Cardiovascular Disease

- MicroRNA exosomes of pasteurized milk: potential pathogens of Western diseases

Prebiotics & Postbiotics

We’re short on space, so we’ll link you to a previous article, and tell you that it’s important against aging too:

Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

An example of how one of Dr. Greger’s most-recommended postbiotics helps against aging, by the way:

- The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans

- Urolithin A improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults

(Urolithin can be found in many plants, and especially those containing tannins)

See also: How to Make Urolithin Postbiotics from Tannins

Caloric restriction / Intermittent fasting

This is about lowering metabolic load and promoting cellular apoptosis (programmed cell death; sounds bad; is good) and autophagy (self-consumption; again, sounds bad; is good).

For example, he cites the intermittent fasters’ 46% lower risk of dying in the subsequent years of follow-up in this longitudinal study:

For brevity we’ll link to our previous IF article, but we’ll revisit caloric restriction in a main feature on of these days:

Fasting Without Crashing? We sort the science from the hype!

Dr. Greger favours caloric restriction over intermittent fasting, arguing that it is easier to adhere to and harder to get wrong if one has some confounding factor (e.g. diabetes, or a medication that requires food at certain times, etc). If adhered to healthily, the benefits appear to be comparable for each, though.

Protein restriction

In contrast to our recent main feature Protein vs Sarcopenia, in which that week’s featured expert argued for high protein consumption levels, protein restriction can, on the other hand, have anti-aging effects. A reminder that our body is a complex organism, and sometimes what’s good for one thing is bad for another!

Dr. Greger offers protein restriction as a way to get many of the benefits of caloric restriction, without caloric restriction. He further notes that caloric restriction without protein restriction doesn’t decrease IGF-1 levels (a marker of aging).

However, for FGF21 levels (these are good and we want them higher to stay younger), what matters more than lowering proteins in general is lowering levels of the amino acid methionine—found mostly in animal products, not plants—so the source of the protein matters:

For example, legumes deliver only 5–10% of the methionine that meat does, for the same amount of protein, so that’s a factor to bear in mind.

NAD+

This is about nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or NAD+ to its friends.

NAD+ levels decline with age, and that decline is a causal factor in aging, and boosting the levels can slow aging:

Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence

Can we get NAD+ from food? We can, but not in useful quantities or with sufficient bioavailability.

Supplements, then? Dr. Greger finds the evidence for their usefulness lacking, in interventional trials.

How to boost NAD+, then? Dr. Greger prescribes…

Exercise! It boosts levels by 127% (i.e., it more than doubles the levels), based on a modest three-week exercise bike regimen:

Skeletal muscle NAMPT is induced by exercise in humans

Another study on resistance training found the same 127% boost:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Egg Noodles vs Soba Noodles – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

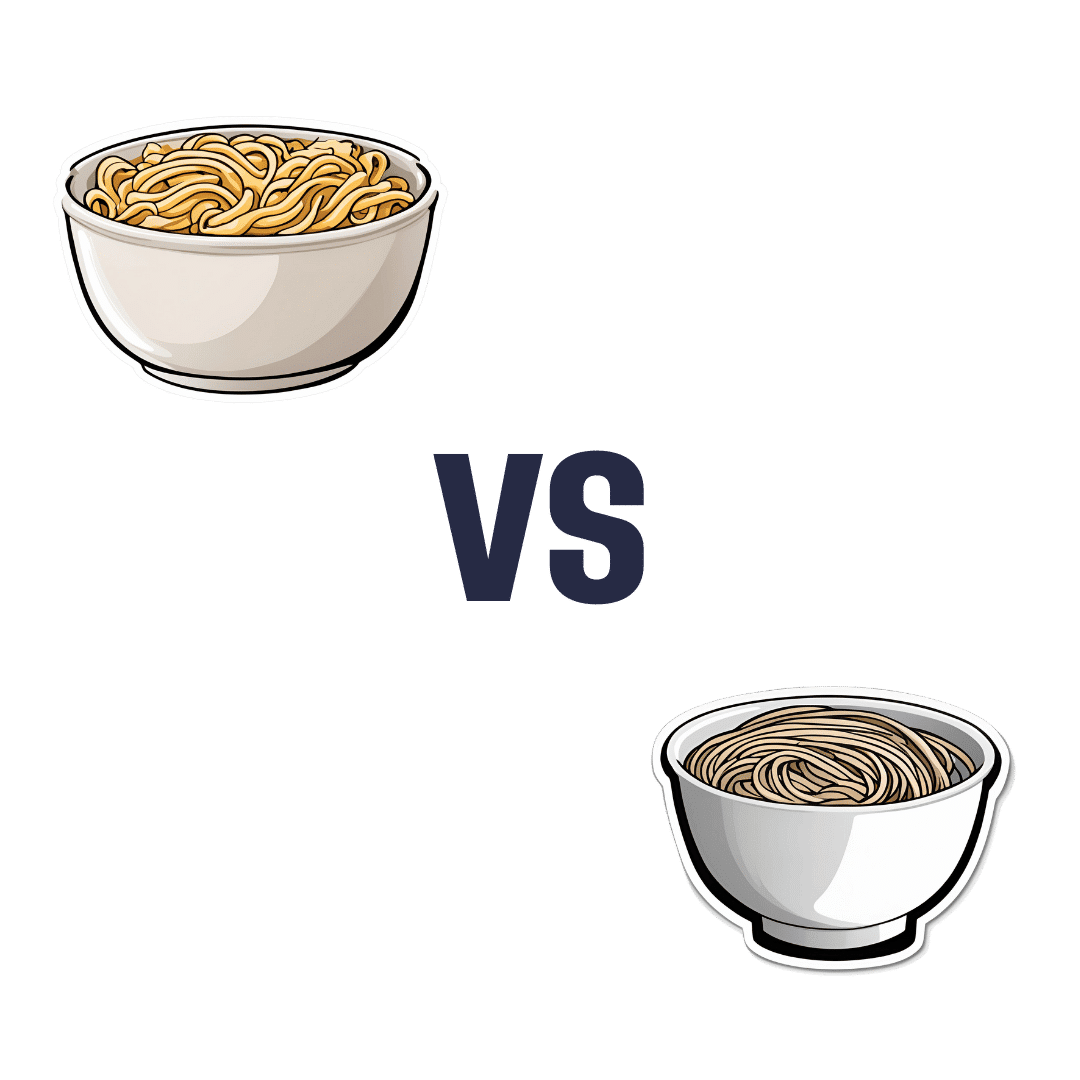

When comparing egg noodles to soba noodles, we picked the soba.

Why?

First of all, for any unfamiliar, soba noodles are made with buckwheat. Buckwheat, for any unfamiliar, is not wheat and does not contain gluten; it’s just the name of a flowering plant that gets used as though a grain, even though it’s technically not.

In terms of macros, egg noodles have slightly more protein 2x the fat (of which, some cholesterol) while soba noodles have very slightly more carbs and 3x the fiber (and, being plant-based, no cholesterol). Given that the carbs are almost equal, it’s a case of which do we care about more: slightly more protein, or 3x the fiber? We’re going with 3x the fiber, and so are calling this category a win for soba.

In the category of vitamins, egg noodles have more of vitamins A, B12, C, D, E, K, and choline, while soba noodles have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, and B9. That’s a 6:6 tie. One could argue that egg noodles’ vitamins are the ones more likely to be a deficiency in people, but on the other hand, soba noodles’ vitamins have the greater margins of difference. So, still a tie.

When it comes to minerals, egg noodles have more calcium and selenium, while soba noodles have more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc. So, this one’s not close; it’s an easy win for soba noodles.

Adding up the sections makes for a clear win for soba noodles, but by all means, enjoy moderate portions of either or both (unless you are vegan or allergic to eggs, in which case, skip the egg noodles and just enjoy the soba!).

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Egg Noodles vs Rice Noodles – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

What Harm Can One Sleepless Night Do?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ll not bury the lede: a study found that just one night of 24-hour sleep deprivation can alter immune cell profiles in young, lean, healthy people to resemble those of people with obesity and chronic inflammation.

Chronic inflammation, in turn, causes very many other chronic diseases, and worsens most of the ones it doesn’t outright cause.

The reason this happens is because in principle, inflammation is supposed to be good for us—it’s our body’s defenses coming to the rescue. However, if we imagine our immune cells as firefighters, then compare:

- A team of firefighters who are in great shape and ready to deploy at a moment’s notice, are mostly allowed to rest, sometimes get training, and get called out to a fire from time time, just enough to keep them on their toes. Today, something in your house caught fire, and they showed up in 5 minutes and put it out safely.

- A team of firefighters who have been pulling 24-hour shifts every day for the past 20 years, getting called out constantly for lost cats, burned toast, wrong numbers, the neighbor’s music, a broken fridge, and even the occasional fire. Today, your printer got jammed so they broke down your door and also your windows just for good measure, and blasted your general desk area with a fire hose, which did not resolve the problem but now your computer itself is broken.

Which team would you rather have?

The former team is a healthy immune system; the latter is the immune system of someone with chronic inflammation.

But if it’s one night, it’s not chronic, right?

Contingently true. However, the problem is that because the immune profile was made to be like the bad team we described (imagine that chaos in your house, now remember that for this metaphor, it’s your body that that’s happening to), the immediate strong negative health impact will already have knock-on effects, which in turn make it more likely that you’ll struggle to get your sleep back on track quickly.

For example, the next night you may oversleep “to compensate”, but then the following day your sleep schedule is now slid back considerably; one thing leads to another, and a month later you’re thinking “I really must sort my sleep out”.

See also: How Regularity Of Sleep Can Be Even More Important Than Duration ← A recent, large (n=72,269) 8-year prospective* observational study of adults aged 40-79 found a strong association between irregular sleep and major cardiovascular events, to such an extent that it was worse than undersleeping.

*this means they started the study at a given point, and measured what happened for the next eight years—as opposed to a retrospective study, which would look at what had happened during the previous 8 years.

What about sleep fragmentation?

In other words: getting sleep, but heavily disrupted sleep.

The answer is: basically the same deal as with missed sleep.

Specifically, elevated proinflammatory cytokines (in this context, that’s bad) and an increase in nonclassical monocytes—as are typically seen in people with obesity and chronic inflammation.

Remember: these were young, lean, healthy participants going into the study, who signed up for a controlled sleep deprivation experiment.

This is important, because the unhealthy inflammatory profile means that people with such are a lot more likely to develop diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and many more things besides. And, famously, most people in the industrialized world are not sleeping that well.

Even amongst 10almonds readers, a health-conscious demographic by nature, 62% of 10almonds readers do not regularly get the prescribed 7–9 hours sleep (i.e. they get under 7 hours).

You can see the data on this one, here: Why You Probably Need More Sleep ← yes, including if you are in the older age range; we bust that myth in the article too!*

*Unless you have a (rare!) mutated ADRB1 gene, which reduces that. But we also cover that in the article, and how to know whether you have it.

With regard to “most people in the industrialized world are not sleeping that well”, this means that most people in the industrialized world are subject to an unseen epidemic of sleep-deprivation-induced inflammation that is creating vulnerability to many other diseases. In short, the lifestyle of the industrialized world (especially: having to work certain hours) is making most of the working population sick.

Dr. Fatema Al-Rashed, lead researcher, concluded:

❝In the long term, we aim for this research to drive policies and strategies that recognize the critical role of sleep in public health.

We envision workplace reforms and educational campaigns promoting better sleep practices, particularly for populations at risk of sleep disruption due to technological and occupational demands.

Ultimately, this could help mitigate the burden of inflammatory diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.❞

You can read the paper in full here: Impact of sleep deprivation on monocyte subclasses and function

What can we do about it?

With regard to sleep, we’ve written so much about this, but here are three key articles that contain a lot of valuable information:

- Get Better Sleep: Beyond The Basics

- Calculate (And Enjoy) The Perfect Night’s Sleep

- Safe Effective Sleep Aids For Seniors

…and with regard to inflammation, a good concise overview of how to dial it down is:

How To Prevent Or Reduce Inflammation

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Cassava vs Parsnip – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cassava to parsnips, we picked the parsnips.

Why?

This one wasn’t close!

In terms of macros, cassava has more than 2x the carbs while parsnips have nearly 3x the fiber, making for a very clear win for parsnips.

In the category of vitamins, cassava has more of vitamins B3 and C, while parsnips have more of vitamins B1, B2, B5, B6, B9, E, and K, with very large margins of difference in the latter two cases. Another overwhelming win for parsnips.

Looking at minerals, cassava is not higher in any minerals, while parsnips have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc; a very one-sided win for parsnips!

So, by all means enjoy either or both (diversity is good), but there’s a clear winner here today, and it’s parsnips.

Want to learn more?

You might like:

What Do The Different Kinds Of Fiber Do? 30 Foods That Rank Highest

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Scarcity Brain – by Michael Easter

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

After a brief overview of theevolutionary psychology underpinnings of the scarcity brain, the author grounds the rest of this book firmly in the present. He explains how the scarcity loop hooks us and why we crave more, and what factors can increase or lessen its hold over us.

As for what things we are wired to consider “potentially scarce any time now” no matter how saturated we are in them, he looks at an array of categories, each with their nuances. From the obvious such as “food” and “stuff“, to understandable “information” and “happiness“, to abstractions like “influence“, he goes to many sources—experts of various kinds from around the world—to explore how we can know “how much is enough”, and—which can be harder—act accordingly.

The key, he argues, is not in simply wanting less, but in understanding why we crave more in the first place, get rid of our worst habits, and use what we already have, better.

Bottom line: if you feel a gnawing sense of needing more “to be on the safe side”, this book can help you to be a little more strategic (and at the same time, less stressed!) about that.

Click here to check out Scarcity Brain, and manage yours more mindfully!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Glycemic Index vs Glycemic Load vs Insulin Index

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How To Actually Use Those Indices

Carbohydrates are essential for our life, and/but often bring about our early demise. It would be a very conveniently simple world if it were simply a matter of “enjoy in moderation”, but the truth is, it’s not that simple.

To take an extreme example, for the sake of clearest illustration: The person who eats an 80% whole fruit diet (and makes up the necessary protein and fats etc in the other 20%) will probably be healthier than the person who eats a “standard American diet”, despite not practising moderation in their fruit-eating activities. The “standard American diet” has many faults, and one of those faults is how it promotes sporadic insulin spikes leading to metabolic disease.

If your breakfast is a glass of orange juice, this is a supremely “moderate” consumption, but an insulin spike is an insulin spike.

Quick sidenote: if you’re wondering why eating immoderate amounts of fruit is unlikely to cause such spikes, but a single glass of orange juice is, check out:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Glycemic Index

The first tool in our toolbox here is glycemic index, or GI.

GI measures how much a carb-containing food raises blood glucose levels, also called blood sugar levels, but it’s just glucose that’s actually measured, bearing in mind that more complex carbs will generally get broken down to glucose.

Pure glucose has a GI of 100, and other foods are ranked from 0 to 100 based on how they compare.

Sometimes, what we do to foods changes its GI.

- Some is because it changed form, like the above example of whole fruit (low GI) vs fruit juice (high GI).

- Some is because of more “industrial” refinement processes, such as whole grain wheat (medium GI) vs white flour and white flour products (high GI)

- Some is because of other changes, like starches that were allowed to cool before being reheated (or eaten cold).

Broadly speaking, a daily average GI of 45 is considered great.

But that’s not the whole story…

Glycemic Load

Glycemic Load, or GL, takes the GI and says “ok, but how much of it was there?”, because this is often relevant information.

Refined sugar may have a high GI, but half a teaspoon of sugar in your coffee isn’t going to move your blood sugar levels as much as a glass of Coke, say—the latter simply has more sugar in, and just the same zero fiber.

GL is calculated by (grams of carbs / 100) x GI, by the way.

But it still misses some important things, so now let’s look at…

Insulin Index

Insulin Index, which does not get an abbreviation (probably because of the potentially confusing appearance of “II”), measures the rise in insulin levels, regardless of glucose levels.

This is important, because a lot of insulin response is independent of blood glucose:

- Some is because of other sugars, some some is in response to fats, and yes, even proteins.

- Some is a function of metabolic base rate.

- Some is a stress response.

- Some remains a mystery!

Another reason it’s important is that insulin drives weight gain and metabolic disorders far more than glucose.

Note: the indices of foods are calculated based on average non-diabetic response. If for example you have Type 1 Diabetes, then when you take a certain food, your rise in insulin is going to be whatever insulin you then take, because your body’s insulin response is disrupted by being too busy fighting a civil war in your pancreas.

If your diabetes is type 2, or you are prediabetic, then a lot of different things could happen depending on the stage and state of your diabetes, but the insulin index is still a very good thing to be aware of, because you want to resensitize your body to insulin, which means (barring any urgent actions for immediate management of hyper- or hypoglycemia, obviously) you want to eat foods with a low insulin index where possible.

Great! What foods have a low insulin index?

Many factors affect insulin index, but to speak in general terms:

- Whole plant foods are usually top-tier options

- Lean and/or white meats generally have lower insulin index than red and/or fatty ones

- Unprocessed is generally lower than processed

- The more solid a food is, generally the lower its insulin index compared to a less solid version of the same food (e.g. baked potatoes vs mashed potatoes; cheese vs milk, etc)

But do remember the non-food factors too! This means where possible:

- reducing/managing stress

- getting frequent exercise

- getting good sleep

- practising intermittent fasting

See for example (we promise you it’s relevant):

Fix Chronic Fatigue & Regain Your Energy, By Science

…as are (especially recommendable!) the two links we drop at the bottom of that page; do check them out if you can

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: