Why scrapping the term ‘long COVID’ would be harmful for people with the condition

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The assertion from Queensland’s chief health officer John Gerrard that it’s time to stop using the term “long COVID” has made waves in Australian and international media over recent days.

Gerrard’s comments were related to new research from his team finding long-term symptoms of COVID are similar to the ongoing symptoms following other viral infections.

But there are limitations in this research, and problems with Gerrard’s argument we should drop the term “long COVID”. Here’s why.

A bit about the research

The study involved texting a survey to 5,112 Queensland adults who had experienced respiratory symptoms and had sought a PCR test in 2022. Respondents were contacted 12 months after the PCR test. Some had tested positive to COVID, while others had tested positive to influenza or had not tested positive to either disease.

Survey respondents were asked if they had experienced ongoing symptoms or any functional impairment over the previous year.

The study found people with respiratory symptoms can suffer long-term symptoms and impairment, regardless of whether they had COVID, influenza or another respiratory disease. These symptoms are often referred to as “post-viral”, as they linger after a viral infection.

Gerrard’s research will be presented in April at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. It hasn’t been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

After the research was publicised last Friday, some experts highlighted flaws in the study design. For example, Steven Faux, a long COVID clinician interviewed on ABC’s television news, said the study excluded people who were hospitalised with COVID (therefore leaving out people who had the most severe symptoms). He also noted differing levels of vaccination against COVID and influenza may have influenced the findings.

In addition, Faux pointed out the survey would have excluded many older people who may not use smartphones.

The authors of the research have acknowledged some of these and other limitations in their study.

Ditching the term ‘long COVID’

Based on the research findings, Gerrard said in a press release:

We believe it is time to stop using terms like ‘long COVID’. They wrongly imply there is something unique and exceptional about longer term symptoms associated with this virus. This terminology can cause unnecessary fear, and in some cases, hypervigilance to longer symptoms that can impede recovery.

But Gerrard and his team’s findings cannot substantiate these assertions. Their survey only documented symptoms and impairment after respiratory infections. It didn’t ask people how fearful they were, or whether a term such as long COVID made them especially vigilant, for example.

New Africa/Shutterstock

In discussing Gerrard’s conclusions about the terminology, Faux noted that even if only 3% of people develop long COVID (the survey found 3% of people had functional limitations after a year), this would equate to some 150,000 Queenslanders with the condition. He said:

To suggest that by not calling it long COVID you would be […] somehow helping those people not to focus on their symptoms is a curious conclusion from that study.

Another clinician and researcher, Philip Britton, criticised Gerrard’s conclusion about the language as “overstated and potentially unhelpful”. He noted the term “long COVID” is recognised by the World Health Organization as a valid description of the condition.

A cruel irony

An ever-growing body of research continues to show how COVID can cause harm to the body across organ systems and cells.

We know from the experiences shared by people with long COVID that the condition can be highly disabling, preventing them from engaging in study or paid work. It can also harm relationships with their friends, family members, and even their partners.

Despite all this, people with long COVID have often felt gaslit and unheard. When seeking treatment from health-care professionals, many people with long COVID report they have been dismissed or turned away.

Last Friday – the day Gerrard’s comments were made public – was actually International Long COVID Awareness Day, organised by activists to draw attention to the condition.

The response from people with long COVID was immediate. They shared their anger on social media about Gerrard’s comments, especially their timing, on a day designed to generate greater recognition for their illness.

Since the start of the COVID pandemic, patient communities have fought for recognition of the long-term symptoms many people faced.

The term “long COVID” was in fact coined by people suffering persistent symptoms after a COVID infection, who were seeking words to describe what they were going through.

The role people with long COVID have played in defining their condition and bringing medical and public attention to it demonstrates the possibilities of patient-led expertise. For decades, people with invisible or “silent” conditions such as ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) have had to fight ignorance from health-care professionals and stigma from others in their lives. They have often been told their disabling symptoms are psychosomatic.

Gerrard’s comments, and the media’s amplification of them, repudiates the term “long COVID” that community members have chosen to give their condition an identity and support each other. This is likely to cause distress and exacerbate feelings of abandonment.

Terminology matters

The words we use to describe illnesses and conditions are incredibly powerful. Naming a new condition is a step towards better recognition of people’s suffering, and hopefully, better diagnosis, health care, treatment and acceptance by others.

The term “long COVID” provides an easily understandable label to convey patients’ experiences to others. It is well known to the public. It has been routinely used in news media reporting and and in many reputable medical journal articles.

Most importantly, scrapping the label would further marginalise a large group of people with a chronic illness who have often been left to struggle behind closed doors.

Deborah Lupton, SHARP Professor, Vitalities Lab, Centre for Social Research in Health and Social Policy Centre, and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Stop Trying To Lose Weight (And Do This Instead)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Lose weight” is a common goal of many people, and it’s especially a common goal handed down from medical authority figures, often as a manner of “kicking the can down the road” with regard to the doctor actually having to do some work. “Lose 20 pounds and then we’ll talk”, etc.

The thing is, it’s often not a very good or helpful goal… Even if it would be healthy for a given person to lose weight. Instead, biochemist Jessie Inchauspé argues, one should set a directly health-giving goal instead, and let any weight loss, if the body agrees it is appropriate, be a by-product of that

She recommends focusing on metabolic health, specifically, her own specialism is blood glucose maintenance. This is something that diabetics deal with (to one degree or another) every day, but it’s something whose importance should not be underestimated for non-diabetics too.

Keep our blood sugar levels healthy, she says, and a lot of the rest of good health will fall into place by itself—precisely because we’re not constantly sabotaging our body (first the pancreas and liver, then the rest of the body like dominoes).

To that end, she offers a multitude of “hacks” that really work.

Her magnum opus, “Glucose Revolution“, explains the science in great detail and does it very well! Not to be mistaken for her shorter, simpler, and entirely pragmatic “do this, then this”-style book, “The Glucose Goddess Method”, which is also great, but doesn’t go into the science more than absolutely necessary; it’s more for the “I’ll trust you; just tell me what I need to know” crowd.

In her own words:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Prefer text?

We’ve covered Inchauspé’s top 10 recommended hacks here:

10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Running or yoga can help beat depression, research shows – even if exercise is the last thing you feel like

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

At least one in ten people have depression at some point in their lives, with some estimates closer to one in four. It’s one of the worst things for someone’s wellbeing – worse than debt, divorce or diabetes.

One in seven Australians take antidepressants. Psychologists are in high demand. Still, only half of people with depression in high-income countries get treatment.

Our new research shows that exercise should be considered alongside therapy and antidepressants. It can be just as impactful in treating depression as therapy, but it matters what type of exercise you do and how you do it.

Walk, run, lift, or dance away depression

We found 218 randomised trials on exercise for depression, with 14,170 participants. We analysed them using a method called a network meta-analysis. This allowed us to see how different types of exercise compared, instead of lumping all types together.

We found walking, running, strength training, yoga and mixed aerobic exercise were about as effective as cognitive behaviour therapy – one of the gold-standard treatments for depression. The effects of dancing were also powerful. However, this came from analysing just five studies, mostly involving young women. Other exercise types had more evidence to back them.

Walking, running, strength training, yoga and mixed aerobic exercise seemed more effective than antidepressant medication alone, and were about as effective as exercise alongside antidepressants.

But of these exercises, people were most likely to stick with strength training and yoga.

Antidepressants certainly help some people. And of course, anyone getting treatment for depression should talk to their doctor before changing what they are doing.

Still, our evidence shows that if you have depression, you should get a psychologist and an exercise plan, whether or not you’re taking antidepressants.

Join a program and go hard (with support)

Before we analysed the data, we thought people with depression might need to “ease into it” with generic advice, such as “some physical activity is better than doing none.”

But we found it was far better to have a clear program that aimed to push you, at least a little. Programs with clear structure worked better, compared with those that gave people lots of freedom. Exercising by yourself might also make it hard to set the bar at the right level, given low self-esteem is a symptom of depression.

We also found it didn’t matter how much people exercised, in terms of sessions or minutes a week. It also didn’t really matter how long the exercise program lasted. What mattered was the intensity of the exercise: the higher the intensity, the better the results.

Yes, it’s hard to keep motivated

We should exercise caution in interpreting the findings. Unlike drug trials, participants in exercise trials know which “treatment” they’ve been randomised to receive, so this may skew the results.

Many people with depression have physical, psychological or social barriers to participating in formal exercise programs. And getting support to exercise isn’t free.

We also still don’t know the best way to stay motivated to exercise, which can be even harder if you have depression.

Our study tried to find out whether things like setting exercise goals helped, but we couldn’t get a clear result.

Other reviews found it’s important to have a clear action plan (for example, putting exercise in your calendar) and to track your progress (for example, using an app or smartwatch). But predicting which of these interventions work is notoriously difficult.

A 2021 mega-study of more than 60,000 gym-goers found experts struggled to predict which strategies might get people into the gym more often. Even making workouts fun didn’t seem to motivate people. However, listening to audiobooks while exercising helped a lot, which no experts predicted.

Still, we can be confident that people benefit from personalised support and accountability. The support helps overcome the hurdles they’re sure to hit. The accountability keeps people going even when their brains are telling them to avoid it.

So, when starting out, it seems wise to avoid going it alone. Instead:

- join a fitness group or yoga studio

get a trainer or an exercise physiologist

- ask a friend or family member to go for a walk with you.

Taking a few steps towards getting that support makes it more likely you’ll keep exercising.

Let’s make this official

Some countries see exercise as a backup plan for treating depression. For example, the American Psychological Association only conditionally recommends exercise as a “complementary and alternative treatment” when “psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy is either ineffective or unacceptable”.

Based on our research, this recommendation is withholding a potent treatment from many people who need it.

In contrast, The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists recommends vigorous aerobic activity at least two to three times a week for all people with depression.

Given how common depression is, and the number failing to receive care, other countries should follow suit and recommend exercise alongside front-line treatments for depression.

I would like to acknowledge my colleagues Taren Sanders, Chris Lonsdale and the rest of the coauthors of the paper on which this article is based.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Michael Noetel, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Good Health From Head To Toe

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

This newsletter has been growing a lot lately, and so have the questions/requests, and we love that! In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

Q: I am now in the “aging” population. A great concern for me is Alzheimers. My father had it and I am so worried. What is the latest research on prevention?

Very important stuff! We wrote about this not long back:

- See: How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

- See also: Brain Food? The Eyes Have It!

(one good thing to note is that while Alzheimer’s has a genetic component, it doesn’t appear to be hereditary per se. Still, good to be on top of these things, and it’s never too early to start with preventive measures!)

Q: Foods that help build stronger bones and cut inflammation? Thank you!

We’ve got you…

For stronger bones / To cut inflammation

That “stronger bones” article is about the benefits of collagen supplementation for bones, but there’s definitely more to say on the topic of stronger bones, so we’ll do a main feature on it sometime soon!

Q: Veganism, staying mentally sharp, best exercises for weight gain?

All great stuff! Let’s do a run-down:

- Veganism? As a health and productivity newsletter, we’ll only be focusing veganism’s health considerations, but it does crop up from time to time! For example:

- Which Plant Milk? (entirely about such)

- Plant vs Animal Protein (mostly about such)

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later) (discusses one benefit of such)

- Staying mentally sharp? You might like the things-against-dementia pieces we linked to in the previous response!

- It’s also worth noting that some kinds of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s, can begin the neurodegenerative process 20 years before symptoms show, and can be influenced by lifestyle choices 20 years before that, so it’s definitely never too early be on top of these things!

- Best exercises for weight gain? We’ll do a main feature one of these days (filled with good science and evidence), but in few words meanwhile: core exercises, large muscle groups, heavy weights, few reps, build up slowly. Squats are King.

Q: I am interested in the following: Aging, Exercise, Diet, Relationships, Purpose, Lowering Stress

You’re going to love our Psychology Sunday editions of 10almonds! You might like some of these…

- Relationships: Seriously Useful Communication Skills!

- Purpose: Are You Flourishing? (There’s a Scale)

- Managing stress: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

- Also about managing stress: Sunday Stress-Buster

- Also applicable to stress: How To Set Your Anxiety Aside

Q: I’d like to know more about type 2 diabetic foot problems

You probably know that the “foot problems” thing has less to do with the feet and more to do with blood and nerves. So, why the feet?

The reason feet often get something like the worst of it, is because they are extremities, and in the case of blood sugars being too high for too long too often, they’re getting more damage as blood has to fight its way back up your body. Diabetic neuropathy happens when nerves are malnourished because the blood that should be keeping them healthy, is instead syrupy and sluggish.

We’ll definitely do a main feature sometime soon on keeping blood sugars healthy, for both types of diabetes plus pre-diabetes and just general advice for all.

In the meantime, here’s some very good advice on keeping your feet healthy in the context of diabetes. This one’s focussed on Type 1 Diabetes, but the advice goes for both:

! Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Loaded Mocha Chocolate Parfait

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Packed with nutrients, including a healthy dose of protein and fiber, these parfait pots can be a healthy dessert, snack, or even breakfast!

You will need (for 4 servings)

For the mocha cream:

- ½ cup almond milk

- ½ cup raw cashews

- ⅓ cup espresso

- 2 tbsp maple syrup

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

For the chocolate sauce:

- 4 tbsp coconut oil, melted

- 2 tbsp unsweetened cocoa powder

- 1 tbsp maple syrup

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

For the other layers:

- 1 banana, sliced

- 1 cup granola, no added sugar

Garnish (optional): 3 coffee beans per serving

Note about the maple syrup: since its viscosity is similar to the overall viscosity of the mocha cream and chocolate sauce, you can adjust this per your tastes, without affecting the composition of the dish much besides sweetness (and sugar content). If you don’t like sweetness, the maple syrup be reduced or even omitted entirely (your writer here is known for her enjoyment of very strong bitter flavors and rarely wants anything sweeter than a banana); if you prefer more sweetness than the recipe called for, that’s your choice too.

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Blend all the mocha cream ingredients. If you have time, doing this in advance and keeping it in the fridge for a few hours (or even up to a week) will make the flavor richer. But if you don’t have time, that’s fine too.

2) Stir all the chocolate sauce ingredients together in a small bowl, and set it aside. This one should definitely not be refrigerated, or else the coconut oil will solidify and separate itself.

3) Gently swirl the the mocha cream and chocolate sauce together. You want a marble effect, not a full mixing. Omit this step if you want clearer layers.

4) Assemble in dessert glasses, alternating layers of banana, mocha chocolate marble mixture (or the two parts, if you didn’t swirl them together), and granola.

5) Add the coffee-bean garnish, if using, and serve!

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

- The Bitter Truth About Coffee (Or Is It?)

- Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

- Cashew Nuts vs Coconut – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

Shockingly, we’ve not previously covered this in a main feature here at 10almonds… Mostly we tend to focus on less well-known supplements. However, in this case, the supplement may be well known, while some of its benefits, we suspect, may come as a surprise.

So…

What is it?

In this case, it’s more of a “what are they?”, because omega-3 fatty acids come in multiple forms, most notably:

- Alpha-linoleic acid (ALA)

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)

- Docosahexanoic acid (DHA)

ALA is most readily found in certain seeds and nuts (chia seeds and walnuts are top contenders), while EPA and DHA are most readily found in certain fish (hence “cod liver oil” being a commonly available supplement, though actually cod aren’t even the best source—salmon and mackerel are better; cod is just cheaper to overfish, making it the cheaper supplement to manufacture).

Which of the three is best, or do we need them all?

There are two ways of looking at this:

- ALA is sufficient alone, because it is a precursor to EPA and DHA, meaning that the body will take ALA and convert it into EPA and DHA as required

- EPA and DHA are superior because they’re already in the forms the body will use, which makes them more efficient

As with most things in health, diversity is good, so you really can’t go wrong by getting some from each source.

Unless you have an allergy to fish or nuts, in which case, definitely avoid those!

What do omega-3 fatty acids do for us, according to actual research?

Against inflammation

Most people know it’s good for joints, as this is perhaps what it’s most marketed for. Indeed, it’s good against inflammation of the joints (and elsewhere), and autoimmune diseases in general. So this means it is indeed good against common forms of arthritis, amongst others:

Read: Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune disease

Against menstrual pain

Linked to the above-referenced anti-inflammatory effects, omega-3s were also found to be better than ibuprofen for the treatment of severe menstrual pain:

Don’t take our word for it: Comparison of the effect of fish oil and ibuprofen on treatment of severe pain in primary dysmenorrhea

Against cognitive decline

This one’s a heavy-hitter. It’s perhaps to be expected of something so good against inflammation (bearing in mind that, for example, a large part of Alzheimer’s is effectively a form of inflammation of the brain); as this one’s so important and such a clear benefit, here are three particularly illustrative studies:

- Inadequate supply of vitamins and DHA in the elderly: implications for brain aging and Alzheimer-type dementia

- Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study

- Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease

Against heart disease

The title says it all in this one:

But what about in patients who do have heart disease?

Mozaffarian and Wu did a huge meta-review of available evidence, and found that in fact, of all the studied heart-related effects, reducing mortality rate in cases of cardiovascular disease was the single most well-evidenced benefit:

How much should we take?

There’s quite a bit of science on this, and—which is unusual for something so well-studied—not a lot of consensus.

However, to summarize the position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics on dietary fatty acids for healthy adults, they recommend a minimum of 250–500 mg combined EPA and DHA each day for healthy adults. This can be obtained from about 8 ounces (230g) of fatty fish per week, for example.

If going for ALA, on the other hand, the recommendation becomes 1.1g/day for women or 1.6g/day for men.

Want to know how to get more from your diet?

Here’s a well-sourced article about different high-density dietary sources:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Yes, you still need to use sunscreen, despite what you’ve heard on TikTok

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Summer is nearly here. But rather than getting out the sunscreen, some TikTokers are urging followers to chuck it out and go sunscreen-free.

They claim it’s healthier to forgo sunscreen to get the full benefits of sunshine.

Here’s the science really says.

Karolina Grabowska/Pexels How does sunscreen work?

Because of Australia’s extreme UV environment, most people with pale to olive skin or other risk factors for skin cancer need to protect themselves. Applying sunscreen is a key method of protecting areas not easily covered by clothes.

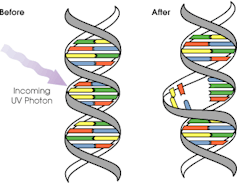

Sunscreen works by absorbing or scattering UV rays before they can enter your skin and damage DNA or supportive structures such as collagen.

When UV particles hit DNA, the excess energy can damage our DNA. This damage can be repaired, but if the cell divides before the mistake is fixed, it causes a mutation that can lead to skin cancers.

The energy from a particle of UV (a photon) causes DNA strands to break apart and reconnect incorrectly. This causes a bump in the DNA strand that makes it difficult to copy accurately and can introduce mutations. NASA/David Herring The most common skin cancers are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Melanoma is less common, but is the most likely to spread around the body; this process is called metastasis.

Two in three Australians will have at least one skin cancer in their lifetime, and they make up 80% of all cancers in Australia.

Around 99% of skin cancers in Australia are caused by excessive exposure to UV radiation.

Excessive exposure to UV radiation also affects the appearance of your skin. UVA rays are able to penetrate deep into the skin, where they break down supportive structures such as elastin and collagen.

This causes signs of premature ageing, such as deep wrinkling, brown or white blotches, and broken capillaries.

Sunscreen can help prevent skin cancers

Used consistently, sunscreen reduces your risk of skin cancer and slows skin ageing.

In a Queensland study, participants either used sunscreen daily for almost five years, or continued their usual use.

At the end of five years, the daily-use group had reduced their risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 40% compared to the other group.

Ten years later, the daily use group had reduced their risk of invasive melanoma by 73%

Does sunscreen block the health-promoting properties of sunlight?

The answer is a bit more complicated, and involves personalised risk versus benefit trade-offs.

First, the good news: there are many health benefits of spending time in the sun that don’t rely on exposure to UV radiation and aren’t affected by sunscreen use.

Sunscreen only filters UV rays, not all light. Ron Lach/Pexels Sunscreen only filters UV rays, not visible light or infrared light (which we feel as heat). And importantly, some of the benefits of sunlight are obtained via the eyes.

Visible light improves mood and regulates circadian rhythm (which influences your sleep-wake cycle), and probably reduces myopia (short-sightedness) in children.

Infrared light is being investigated as a treatment for several skin, neurological, psychiatric and autoimmune disorders.

So what is the benefit of exposing skin to UV radiation?

Exposing the skin to the sun produces vitamin D, which is critical for healthy bones and muscles.

Vitamin D deficiency is surprisingly common among Australians, peaking in Victoria at 49% in winter and being lowest in Queensland at 6% in summer.

Luckily, people who are careful about sun protection can avoid vitamin D deficiency by taking a supplement.

Exposing the skin to UV radiation might have benefits independent of vitamin D production, but these are not proven. It might reduce the risk of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis or cause release of a chemical that could reduce blood pressure. However, there is not enough detail about these benefits to know whether sunscreen would be a problem.

What does this mean for you?

There are some benefits of exposing the skin to UV radiation that might be blunted by sunscreen. Whether it’s worth foregoing those benefits to avoid skin cancer depends on how susceptible you are to skin cancer.

If you have pale skin or other factors that increase you risk of skin cancer, you should aim to apply sunscreen daily on all days when the UV index is forecast to reach 3.

If you have darker skin that rarely or never burns, you can go without daily sunscreen – although you will still need protection during extended times outdoors.

For now, the balance of evidence suggests it’s better for people who are susceptible to skin cancer to continue with sun protection practices, with vitamin D supplementation if needed.

Katie Lee, PhD Candidate, Dermatology Research Centre, The University of Queensland and Rachel Neale, Principal research fellow, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: