Top 5 Foods Seniors Should Eat To Sleep Better Tonight (And 5 To Avoid)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Michael Breus, a sleep specialist, advises:

A prescription for rest

Dr. Breus’s top 5 foods to eat for a good night’s sleep are:

1) Chia seeds: high in fiber, protein, omega-3s, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and tryptophan, they help raise melatonin levels for better sleep. The high fiber content also reduces late-night snacking, and in any case, it’s recommended to eat them 2–3 hours before bed. As for how, they can be added to smoothies, baked goods, salads, or made into chia seed pudding.

2) Nuts (especially pistachios & almonds): both of these nuts are rich in B vitamins and melatonin, so take your pick! He does recommend, however, no more than ¼ cup about 1.5 hours before bed. Either can be eaten as-is or with an unsweetened Greek yogurt.

3) Bananas (especially banana tea): contain magnesium, especially in the peel. Boil an organic banana (with peel) in water and drink the water, which provides magnesium and helps improve sleep. It’s recommended to drink it about an hour before bed.

10almonds tip: he doesn’t mention this, but if you prefer, you can also simply eat it—banana peel is perfectly edible, and is not tough when cooked. If you’ve ever had plantains, you’ll know how they are, and bananas (and their peel) are much softer than plantains. Boiling is fine, or alternatively you can wrap them in foil and bake them. The traditional way is to cook them in the leaves, but chances are you live somewhere that doesn’t grow bananas locally and so they didn’t come with leaves, so foil is fine.

4) Tart cherries: are rich in melatonin, antioxidants, and other anti-inflammatory compounds, which all help with falling asleep faster and reducing night awakenings. Can be consumed as juice, dried fruit, or tart cherry extract capsules. Suggested intake: once in the morning and once an hour before bed.

5) Kiwis: are high in serotonin, which aids melatonin production and sleep. This also helps regulate cortisol levels (lower cortisol promotes sleep). He recommends eating kiwi fruit about 2 hours before bed.

Also, in the category of foods (or rather: food types) to avoid before bed…

- High quantities of red meat: can disrupt sleep-related amino acid balance.

- Acidic foods: can cause acid reflux.

- High sugar foods: can slow melatonin production when consumed in the evening.

- Caffeine-rich foods & drinks: includes chocolate and coffee; avoid in the evening.

- Large meals before bed: digestion is less efficient when lying down, causing sleep disruption.

For more on all of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Calculate (And Enjoy) The Perfect Night’s Sleep ← Our “Expert Insights” main feature on Dr. Breus

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The first pig kidney has been transplanted into a living person. But we’re still a long way from solving organ shortages

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In a world first, we heard last week that US surgeons had transplanted a kidney from a gene-edited pig into a living human. News reports said the procedure was a breakthrough in xenotransplantation – when an organ, cells or tissues are transplanted from one species to another. https://www.youtube.com/embed/cisOFfBPZk0?wmode=transparent&start=0 The world’s first transplant of a gene-edited pig kidney into a live human was announced last week.

Champions of xenotransplantation regard it as the solution to organ shortages across the world. In December 2023, 1,445 people in Australia were on the waiting list for donor kidneys. In the United States, more than 89,000 are waiting for kidneys.

One biotech CEO says gene-edited pigs promise “an unlimited supply of transplantable organs”.

Not, everyone, though, is convinced transplanting animal organs into humans is really the answer to organ shortages, or even if it’s right to use organs from other animals this way.

There are two critical barriers to the procedure’s success: organ rejection and the transmission of animal viruses to recipients.

But in the past decade, a new platform and technique known as CRISPR/Cas9 – often shortened to CRISPR – has promised to mitigate these issues.

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR gene editing takes advantage of a system already found in nature. CRISPR’s “genetic scissors” evolved in bacteria and other microbes to help them fend off viruses. Their cellular machinery allows them to integrate and ultimately destroy viral DNA by cutting it.

In 2012, two teams of scientists discovered how to harness this bacterial immune system. This is made up of repeating arrays of DNA and associated proteins, known as “Cas” (CRISPR-associated) proteins.

When they used a particular Cas protein (Cas9) with a “guide RNA” made up of a singular molecule, they found they could program the CRISPR/Cas9 complex to break and repair DNA at precise locations as they desired. The system could even “knock in” new genes at the repair site.

In 2020, the two scientists leading these teams were awarded a Nobel prize for their work.

In the case of the latest xenotransplantation, CRISPR technology was used to edit 69 genes in the donor pig to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and knock out harmful pig genes. https://www.youtube.com/embed/UKbrwPL3wXE?wmode=transparent&start=0 How does CRISPR work?

A busy time for gene-edited xenotransplantation

While CRISPR editing has brought new hope to the possibility of xenotransplantation, even recent trials show great caution is still warranted.

In 2022 and 2023, two patients with terminal heart diseases, who were ineligible for traditional heart transplants, were granted regulatory permission to receive a gene-edited pig heart. These pig hearts had ten genome edits to make them more suitable for transplanting into humans. However, both patients died within several weeks of the procedures.

Earlier this month, we heard a team of surgeons in China transplanted a gene-edited pig liver into a clinically dead man (with family consent). The liver functioned well up until the ten-day limit of the trial.

How is this latest example different?

The gene-edited pig kidney was transplanted into a relatively young, living, legally competent and consenting adult.

The total number of gene edits edits made to the donor pig is very high. The researchers report making 69 edits to inactivate viral genes, “humanise” the pig with human genes, and to knockout harmful pig genes.

Clearly, the race to transform these organs into viable products for transplantation is ramping up.

From biotech dream to clinical reality

Only a few months ago, CRISPR gene editing made its debut in mainstream medicine.

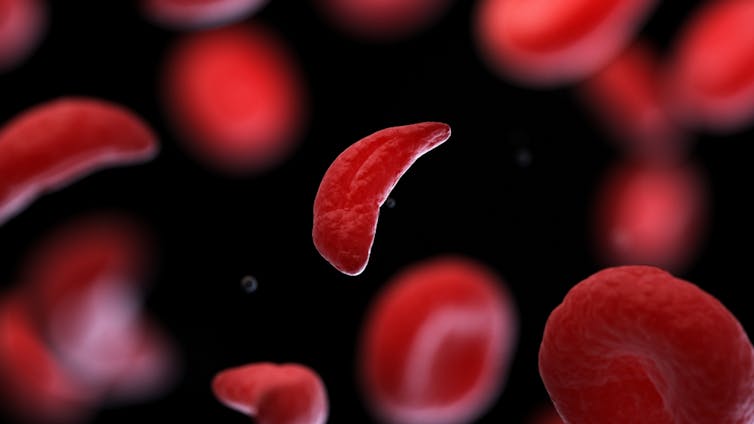

In November, drug regulators in the United Kingdom and US approved the world’s first CRISPR-based genome-editing therapy for human use – a treatment for life-threatening forms of sickle-cell disease.

The treatment, known as Casgevy, uses CRISPR/Cas-9 to edit the patient’s own blood (bone-marrow) stem cells. By disrupting the unhealthy gene that gives red blood cells their “sickle” shape, the aim is to produce red blood cells with a healthy spherical shape.

Although the treatment uses the patient’s own cells, the same underlying principle applies to recent clinical xenotransplants: unsuitable cellular materials may be edited to make them therapeutically beneficial in the patient.

CRISPR technology is aiming to restore diseased red blood cells to their healthy round shape. Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock We’ll be talking more about gene-editing

Medicine and gene technology regulators are increasingly asked to approve new experimental trials using gene editing and CRISPR.

However, neither xenotransplantation nor the therapeutic applications of this technology lead to changes to the genome that can be inherited.

For this to occur, CRISPR edits would need to be applied to the cells at the earliest stages of their life, such as to early-stage embryonic cells in vitro (in the lab).

In Australia, intentionally creating heritable alterations to the human genome is a criminal offence carrying 15 years’ imprisonment.

No jurisdiction in the world has laws that expressly permits heritable human genome editing. However, some countries lack specific regulations about the procedure.

Is this the future?

Even without creating inheritable gene changes, however, xenotransplantation using CRISPR is in its infancy.

For all the promise of the headlines, there is not yet one example of a stable xenotransplantation in a living human lasting beyond seven months.

While authorisation for this recent US transplant has been granted under the so-called “compassionate use” exemption, conventional clinical trials of pig-human xenotransplantation have yet to commence.

But the prospect of such trials would likely require significant improvements in current outcomes to gain regulatory approval in the US or elsewhere.

By the same token, regulatory approval of any “off-the-shelf” xenotransplantation organs, including gene-edited kidneys, would seem some way off.

Christopher Rudge, Law lecturer, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We speak often about the importance of dietary diversity, and of that, especially diversity of plants in one’s diet, but we’ve never really focused on it as a main feature, so that’s what we’re going to do today.

Specifically, you may have heard the advice to “eat 30 different kinds of plants per week”. But where does that come from, and is it just a number out of a hat?

The magic number?

It is not, in fact, a number out of a hat. It’s from a big (n=11,336) study into what things affect the gut microbiome for better or for worse. It was an observational population study, championing “citizen science” in which volunteers tracked various things and collected and sent in various samples for analysis.

The most significant finding of this study was that those who consumed more than 30 different kinds of plants per week, had a much better gut microbiome than those who consumed fewer than 10 different kinds of plants per week (there is a bell curve at play, and it gets steep around 10 and 30):

American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research

Why do I care about having a good gut microbiome?

Gut health affects almost every other kind of health; it’s been called “the second brain” for the various neurotransmitters and other hormones it directly makes or indirectly regulates (which in turn affect every part of your body), and of course there is the vagus nerve connecting it directly to the brain, impacting everything from food cravings to mood swings to sleep habits.

See also:

Any other benefits?

Yes there are! Let’s not forget: as we see often in our “This or That” section, different foods can be strong or weak in different areas of nutrition, so unless we want to whip out a calculator and database every time we make food choices, a good way to cover everything is to simply eat a diverse diet.

And that goes not just for vitamins and minerals (which would be true of animal products also), but in the case of plants, a wide range of health-giving phytochemicals too:

Measuring Dietary Botanical Diversity as a Proxy for Phytochemical Exposure

Ok, I’m sold, but 30 is a lot!

It is, but you don’t have to do all 30 in your first week of focusing on this, if you’re not already accustomed to such diversity. You can add in one or two new ones each time you go shopping, and build it up.

As for “what counts”: we’re counting unprocessed or minimally-processed plants. So for example, an apple is an apple, as are dried apple slices, as is apple sauce. Any or all of those would count as 1 plant type.

Note also that we’re counting types, not totals. If you’re having apple slices with apple sauce, for some reason? That still only counts as 1.

However, while apple sauce still counts as apples (minimally processed), you cannot eat a cake and say “that’s 2 because there was wheat and sugar cane somewhere in its dim and distant history”.

Nor is your morning espresso a fruit (by virtue of coffee beans being the fruit of the plant, botanically speaking). However, it would count as 1 plant type if you eat actual coffee beans—this writer has been known to snack on such; they’re only healthy in very small portions though, because their saturated fat content is a little high.

You, however, count grains in general, as well as nuts and seeds, not just fruits and vegetables. As for herbs and spices, they count for ¼ each, except for salt, which might get lumped in with spices but is of course not a plant.

How to do it

There’s a reason we’re doing this in our Saturday Life Hacks edition. Here are some tips for getting in far more plants than you might think, a lot more easily than you might think:

- Buy things ready-mixed. This means buying the frozen mixed veg, the frozen mixed chopped fruit, the mixed nuts, the mixed salad greens etc. This way, when you’re reaching for one pack of something, you’re getting 3–5 different plants instead of one.

- Buy things individually, and mix them for storage. This is a more customized version of the above, but in the case of things that keep for at least a while, it can make lazy options a lot more plentiful. Suddenly, instead of rice with your salad you’re having sorghum, millet, buckwheat, and quinoa. This trick also works great for dried berries that can just be tipped into one’s morning oatmeal. Or, you know, millet, oats, rye, and barley. Suddenly, instead of 1 or 2 plants for breakfast you have maybe 7 or 8.

- Keep a well-stocked pantry of shelf-stable items. This is good practice anyway, in case of another supply-lines shutdown like at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. But for plant diversity, it means that if you’re making enchiladas, then instead using kidney beans because that’s what’s in the cupboard, you can raid your pantry for kidney beans, black beans, pinto beans, fava beans, etc etc. Yes, all of them; that’s a list, not a menu.

- Shop in the discount section of the supermarket. You don’t have shop exclusively there, but swing by that area, see what plants are available for next to nothing, and buy at least one of each. Figure out what to do with it later, but the point here is that it’s a good way to get suggestions of plants that you weren’t actively looking for—and novelty is invariably a step into diversity.

- Shop in a different store. You won’t be able to beeline the products you want on autopilot, so you’ll see other things on the way. Also, they may have things your usual store doesn’t.

- Shop in person, not online—at least as often as is practical. This is because when shopping for groceries online, the store will tend to prioritize showing you items you’ve bought before, or similar items to those (i.e. actually the same item, just a different brand). Not good for trying new things!

- Consider a meal kit delivery service. Because unlike online grocery shopping, this kind of delivery service will (usually) provide you with things you wouldn’t normally buy. Our sometimes-sponsor Purple Carrot is a fine option for this, but there are plenty of others too.

- Try new recipes, especially if they have plants you don’t normally use. Make a note of the recipe, and go out of your way to get the ingredients; if it seems like a chore, reframe it as a little adventure instead. Honestly, it’s things like this that keep us young in more ways than just what polyphenols can do!

- Hide the plants. Whether or not you like them; hide them just because it works in culinary terms. By this we mean; blend beans into that meaty sauce; thicken the soup with red lentils, blend cauliflower into the gravy. And so on.

One more “magic 30”, while we’re at it…

30g fiber per day makes a big (positive) difference to many aspects of health. Obviously, plants are where that comes from, so there’s a big degree of overlap here, but most of the tips we gave are different, so for double the effectiveness, check out:

Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

I’m a medical forensic examiner. Here’s what people can expect from a health response after a sexual assault

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

An estimated one in five women and one in 16 men in Australia have experienced sexual violence.

After such a traumatic experience, it’s understandable many are unsure if they want to report it to the police. In fact, less than 10% of Australian women who experience sexual assault ever make a police report.

In Australia there is no time limit on reporting sexual assault to police. However, there are tight time frames for collecting forensic evidence, which can sometimes be an important part of the police investigation, whether it’s commenced at the time or later.

This means the decision of whether or not to undergo a medical forensic examination needs to be made quite quickly after an assault.

I work as a medical forensic examiner. Here’s what you can expect if you present for a medical forensic examination after a sexual assault.

fizkes/Shutterstock A team of specialists

There are about 100 sexual assault services throughout Australia providing 24-hour care. As with other areas of health care, there are extra challenges in regional and rural areas, where there are often further distances to travel and staff shortages.

Sexual assault services in Australia are free regardless of Medicare status. To find your nearest service you can call 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) or Full Stop Australia (1800 385 578) who can also provide immediate telephone counselling support.

It’s important to call the local sexual assault service before turning up. They can provide the victim-survivor with information and advice to prevent delays and make the process as helpful as possible.

The consultation usually occurs in a hospital emergency department which has a designated forensic suite, or in a specialised forensic service.

The victim-survivor is seen by a doctor or nurse trained in medical and forensic care. There’s a sexual assault counsellor, crisis worker or social worker present to support the patient and offer counselling advice. This is called an “integrated response” with medical and psychosocial staff working together.

In most cases the victim-survivor can have their own support person present too.

Depending on what the victim-survivor wants, the doctor or nurse will take a history of the assault to guide any medical care which may be needed (such as emergency contraception) and to guide the examination.

Sexual assault services are always very aware of giving victim-survivors a choice about having a medical forensic examination. If a person presents to a sexual assault service, they can receive counselling and medical care without undergoing a forensic examination if they do not wish to. https://www.youtube.com/embed/CGlbTgia0Ek?wmode=transparent&start=0 Sexual assault services are inclusive of all genders.

Collecting forensic samples

Samples collected during a medical forensic examination can sometimes identify the perpetrator’s DNA or intoxicating substances (alcohol or drugs that might be relevant to the investigation). The window of opportunity to collect these samples can be as short as 12 hours, or up to 5–7 days, depending on the nature of the sexual assault.

In most of Australia, an adult who has experienced a recent sexual assault can be offered a medical forensic examination without making a report to police.

Depending on the state or territory, the forensic samples can usually be stored for 3 to 12 months (up to 100 years in Tasmania). This allows the victim-survivor time to decide if they want to release them to police for processing.

The doctor or nurse will collect the samples using a sexual assault investigation kit, or a “rape kit”.

Collecting these samples might involve taking swabs to try to detect DNA from external and internal genital areas and anywhere there may have been DNA transfer. This can be from skin cells, where the perpetrator touched the victim-survivor, or from bodily fluids including semen or saliva.

The doctor or nurse carrying out the examination do their best to minimise re-traumatisation, by providing the victim-survivor information, choices and control at every step of the process.

The victim-survivor can usually have a support person with them. Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock How about STIs and pregnancy?

During the consultation, the doctor or nurse will address any concerns about sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancy, if applicable.

In most cases the risk of STIs is small. But follow-up testing at 1–2 weeks for infections such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea, and at 6–12 weeks for infections such as syphilis and HIV, is usually recommended.

Emergency contraception (sometimes called the “morning after pill”) can be provided to prevent pregnancy. It can be taken up to five days after sexual assault (but the sooner the better) with follow-up pregnancy testing recommended at 2–3 weeks.

Things have improved over time

When I was a junior doctor in the late 90s, taking forensic swabs was usually the responsibility of the busy obstetrics and gynaecology trainee in the emergency department, who was often managing multiple patients and had little training in forensics. There was also usually no supportive counsellor.

Anecdotally, both the doctor and the patient were traumatised by this experience. Research shows that when specialised, integrated services are not provided, victim-survivors’ feelings of powerlessness are magnified.

But the way we carry out medical forensic examinations after sexual assault in Australia has improved over the years.

With patient-centred practices, and designated forensic and counselling staff, the experience for the patient is thought to be empowering rather than re-traumatising.

Our research

In new research published in the Australian Journal of General Practice, my colleagues and I explored the experience of the medical forensic examination from the victim-survivor’s perspective.

We surveyed 291 patients presenting to a sexual assault service in New South Wales (where I work) over four years.

Some 75% of patients reported the examination was reassuring and another 20% reported it was OK. Only 2% reported that it was traumatising. The majority (98%) said they would recommend a friend present to a sexual assault service if they were in a similar situation.

While patients spoke positively about the care they received, many commented that the sexual assault service was not visible enough. They didn’t know how to find it or even that it existed.

We know many victim-survivors don’t present to a sexual assault service or undergo a medical forensic examination after a sexual assault. So we need to do more to increase the visibility of these services.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Mary Louise Stewart, Senior Career Medical Officer, Northern Sydney Local Health District; PhD Candidate, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Ashwagandha: The Root of All Even-Mindedness?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ashwagandha: The Root Of All Even-Mindedness?

In the past few years, Ashwagandha root has been enjoying popular use in consumer products ranging from specialist nootropic supplement stacks, to supermarket teas and hot chocolates.

This herb is considered to have a calming effect, but the science goes a lot deeper than that. Let’s take a look!

Last summer, a systematic review was conducted, that asked the question:

Does Ashwagandha supplementation have a beneficial effect on the management of anxiety and stress?

While they broadly found the answer was “yes”, they expressed low confidence, and even went so far as to say there was contradictory evidence. We (10almonds) were not able to find any contradictory evidence, and their own full article had been made inaccessible to the public, so we couldn’t double-check theirs.

We promptly did our own research review, and we found many studies this year supporting Ashwaghanda’s use for the management of anxiety and stress, amongst other benefits.

First, know: Ashwagandha’s scientific name is “Withania somnifera”, so if you see that (or a derivative of it) mentioned in a paper or extract, it’s the same thing.

Onto the benefits…

A study from the same summer investigated “the efficacy of Withania somnifera supplementation on adults’ cognition and mood”, and declared that:

“in conclusion, Ashwagandha supplementation may improve the physiological, cognitive, and psychological effects of stress.”

We notice the legalistic “may improve”, but the data itself seems more compelling than that, because the study showed that it in fact “did improve” those things. Specifically, Ashwagandha out-performed placebo in most things they measured, and most (statistically) significantly, reduced cortisol output measurably. Cortisol, for any unfamiliar, is “the stress hormone”.

Another study that looked into its anti-stress properties is this one:

Ashwagandha Modulates Stress, Sleep Dynamics, and Mental Clarity

This study showed that Ashwagandha significantly outperformed placebo in many ways, including:

- sleep quality

- cognitive function

- energy, and

- perceptions of stress management.

Ashwagandha is popular among students, because it alleviates stress while also promising benefits to memory, attention, and thinking. So, this study on students caught our eye:

Their findings demonstrated that Ashwagandha increased college students’ perceived well-being through supporting sustained energy, heightened mental clarity, and enhanced sleep quality.

That was about perceived well-being and based on self-reports, though

So: what about hard science?

A later study (in September) found supplementation with 400 mg of Ashwagandha improved executive function, helped sustain attention, and increased short-term/working memory.

Read the study: Effects of Acute Ashwagandha Ingestion on Cognitive Function

❝But aside from the benefits regarding stress, anxiety, sleep quality, cognitive function, energy levels, attention, executive function, and memory, what has Ashwagandha ever done for us?❞

Well, there have been studies investigating its worth against depression, like this one:

Can Traditional Treatment Such as Ashwagandha Be Beneficial in Treating Depression?

Their broad answer: Ashwagandha works against depression, but they don’t know how it works.

They did add: “Studies also show that ashwagandha may bolster the immune system, increase stamina, fight inflammation and infection, combat tumors*, reduce stress, revive the libido, protect the liver and soothe jangled nerves.

That’s quite a lot, including a lot of physical benefits we’ve not explored in this research review which was more about Ashwagandha’s use as a nootropic!

We’ve been focusing on the more mainstream, well-studied benefits, but for any interested in Ashwagandha’s anti-cancer potential, here’s an example:

Evaluating anticancer properties of [Ashwagandha Extract]-a potent phytochemical

In summary:

There is a huge weight of evidence (of which we’ve barely skimmed the surface here in this newsletter, but there’s only so much we can include, so we try to whittle it down to the highest quality most recent most relevant research) to indicate that Ashwagandha is effective…

- Against stress

- Against anxiety

- Against depression

- For sleep quality

- For memory (working, short-term, and long-term)

- For mental clarity

- For attention

- For stamina

- For energy levels

- For libido

- For immune response

- Against inflammation

- Against cancer

- And more*

*(seriously, this is not hyperbole… We didn’t even look at its liver-protective functions, for instance)

Bottom line:

You’d probably like some Ashwagandha now, right? We know we would.

We don’t sell it (or anything else, for that matter), but happily the Internet does:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Undoing The Damage Of Life’s Hard Knocks

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sometimes, What Doesn’t Kill Us Makes Us Insecure

We’ve written before about Complex PTSD, which is much more common than the more popularly understood kind:

Given that C-PTSD affects so many people (around 1 in 5, but really, do read the article above! It explains it better than we have room to repeat today), it seems like a good idea to share tips for managing it.

(Last time, we took all the space for explaining it, so we just linked to some external resources at the end)

What happened to you?

PTSD has (as a necessity, as part of its diagnostic criteria) a clear event that caused it, which makes the above question easy to answer.

C-PTSD often takes more examination to figure out what tapestry of circumstances (and likely but not necessarily: treatment by other people) caused it.

Often it will feel like “but it can’t be that; that’s not that bad”, or “everyone has things like that” (in which case, you’re probably one of the one in five).

The deeper questions

Start by asking yourself: what are you most afraid of, and why? What are you most ashamed of? What do you fear that other people might say about you?

Often there is a core pattern of insecurity that can be summed up in a simple, harmful, I-message, e.g:

- I am a bad person

- I am unloveable

- I am a fake

- I am easy to hurt

- I cannot keep my loved ones safe

…and so forth.

For a bigger list of common insecurities to see what resonates, check out:

Basic Fears/Insecurities, And Their Corresponding Needs/Desires

Find where they came from

You probably learned bad beliefs, and consequently bad coping strategies, because of bad circumstances, and/or bad advice.

- When a parent exclaimed in anger about how stupid you are

- When a partner exclaimed in frustration that always mess everything up

- When an employer told you you weren’t good enough

…or maybe they told you one thing, and showed you the opposite. Or maybe it was entirely non-verbal circumstances:

- When you gambled on a good idea and lost everything

- When you tried so hard at some important endeavour and failed

- When you thought someone could be trusted, and learned the hard way that you were wrong

These are “life’s difficult bits”, but when we’ve lived through a whole stack of them, it’s less like a single shattering hammer-blow of PTSD, and more like the consistent non-stop tap tap tap that ends up doing just as much damage in the long run.

Resolve them

That may sound a bit like a “and quickly create world peace” level of task, but we have tools:

Ask yourself: what if…

…it had been different? Take some time and indulge in a full-blown fantasy of a life that was better. Explore it. How would those different life lessons, different messages, have impacted who you are, your personality, your behaviour?

This is useful, because the brain is famously bad at telling real memories from false ones. Consciously, you’ll know that one was an exploratory fantasy, but to your brain, it’s still doing the appropriate rewiring. So, little by little, neuroplasticity will do its thing.

Tell yourself a better lie

We borrowed this one from the title of a very good book which we’ve reviewed previously.

This idea is not about self-delusion, but rather that we already express our own experiences as a sort of narrative, and that narrative tends to contain value judgements that are often not useful, e.g. “I am stupid”, “I am useless”, and all the other insecurities we mentioned earlier. Some simple examples might be:

- “I had a terrible childhood” → “I have come so far”

- “I should have known better” → “I am wiser now”

- “I have lost so much” → “I have experienced so much”

So, replacing that self-talk can go a long way to re-writing how secure we feel, and therefore how much trauma-response (ideally: none!) we have to stimuli that are not really as threatening as we sometimes feel they are (a hallmark of PTSD in general).

Here’s a guide to more ways:

How To Get Your Brain On A More Positive Track (Without Toxic Positivity)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Walking… Better.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Walking… Better.

We recently reviewed “52 Ways To Walk” by Annabel Streets. You asked us to share some more of our learnings from that book, and… Obviously we can’t do all 52, nor go into such detail, but here are three top tips inspired by that book…

Walk in the cold!

While cold weather is often seen as a reason to not walk, in fact, it has numerous health benefits, the most exciting of which might be:

Walking in the cold causes us to convert white and yellow fat into the healthier brown fat. If you didn’t know about this, neither did scientists until about 15 years ago.

In fact, scientists didn’t even know that adult humans could even have brown adipose tissue! It was really quite groundbreaking.

In case you missed it: The Changed Metabolic World with Human Brown Adipose Tissue: Therapeutic Visions

Work while you walk!

Obviously this is only appropriate for some kinds of work… but if in your life you have any kind of work that is chiefly thinking, a bunch of it can be done while walking.

Open your phone’s note-taking app, lock the screen and pocket your phone, and think on some problem that you need to solve. Whenever you have an “aha” moment, take out your phone and make a quick note on the go.

For that matter, if you have the money and space (or are fortunate to have an employer disposed towards facilitating such), you could even set up a treadmill desk… At worst, it wouldn’t harm your work (and it’ll be a LOT better than sitting for so long).

Walk within an hour of waking!

No, this doesn’t mean that if you don’t get out of the house within 60 minutes you say “Oh no, missed the window, guess it’s a day in today”

But it does mean: in the evening, make preparations to head out first thing in the morning. Set out your clothes and appropriate footwear, find your flask to fill with the beverage of your choice in the morning and set that with them.

Then, when morning arrives… do your morning necessaries (e.g. some manner of morning ablutions and perhaps a light breakfast), make that drink for your flask, and hit the road.

Why? We’ll tell you a secret:

You ever wondered why some people seem to be more able to keep a daylight-regulated circadian rhythm than others? It’s not just about smartphones and coffees…

This study found that getting sunlight (not electric light, not artificial sunlight, but actual sunlight, from the sun, even if filtered through partial cloud) between 08:30—09:00 resulted in higher levels of a protein called PER2. PER2 is critical for setting circadian rhythms, improving metabolism, and fortifying blood vessels.

Besides, on a more simplistic level, it’s also a wonderful and energizing start to a healthy and productive day!

Read: Beneficial effects of daytime light exposure on daily rhythms, metabolic state and affect

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: