Natural Tips for Falling Asleep

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Questions and Answers at 10almonds

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

This newsletter has been growing a lot lately, and so have the questions/requests, and we love that! In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

How to get to sleep at night as fast and as naturally as possible? Thank you!

We’ll definitely write more on that! You might like these articles we wrote already, meanwhile:

- Beating The Insomnia Blues ← this one is general advice and tips

- Time For Some Pillow Talk ← this one compares and reviews some popular sleep apps

- Insomnia? High Blood Pressure? Try these! ← this one tackles the matter from a dietary angle

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gut-Healthy Sunset Soup

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

So-called for its gut-healthy ingredients, and its flavor profile being from the Maghreb (“Sunset”) region, the western half of the N. African coast.

You will need

- 1 can chickpeas (do not drain)

- 1 cup low-sodium vegetable stock

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 1 carrot, finely chopped

- 2 tbsp sauerkraut, drained and chopped (yes, it is already chopped, but we want it chopped smaller so it can disperse evenly in the soup)

- 2 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tbsp harissa paste (adjust per your heat preference)

- 1 tbsp ras el-hanout

- ¼ bulb garlic, crushed

- Juice of ½ lemon

- ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Optional: herb garnish; we recommend cilantro or flat-leaf parsley

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat a little oil in a sauté pan or similar (something suitable for combination cooking, as we’ll be frying first and then adding liquids), and fry the onion and carrot until the onion is soft and translucent; about 5 minutes.

2) Stir in the garlic, tomato paste, harissa paste, and ras el-hanout, and fry for a further 1 minute.

3) Add the remaining ingredients* except the lemon juice. Bring to the boil and then simmer for 5 minutes.

*So yes, this includes adding the “chickpea water” also called “aquafaba”; it adds flavor and also gut-healthy fiber in the form of oligosaccharides and resistant starches, which your gut microbiota can use to make short-chain fatty acids, which improve immune function and benefit the health in more ways than we can reasonably mention as a by-the-way in a recipe.

4) Stir in the lemon juice, and serve, adding a herb garnish if you wish.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← today’s recipe scored 5/5 of these, plus quite a few more! Remember that ras el-hanout is a spice blend, so if you’re thinking “wait, where’s the…?” then it’s in the ras el-hanout 😉

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More ← not to be underestimated!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

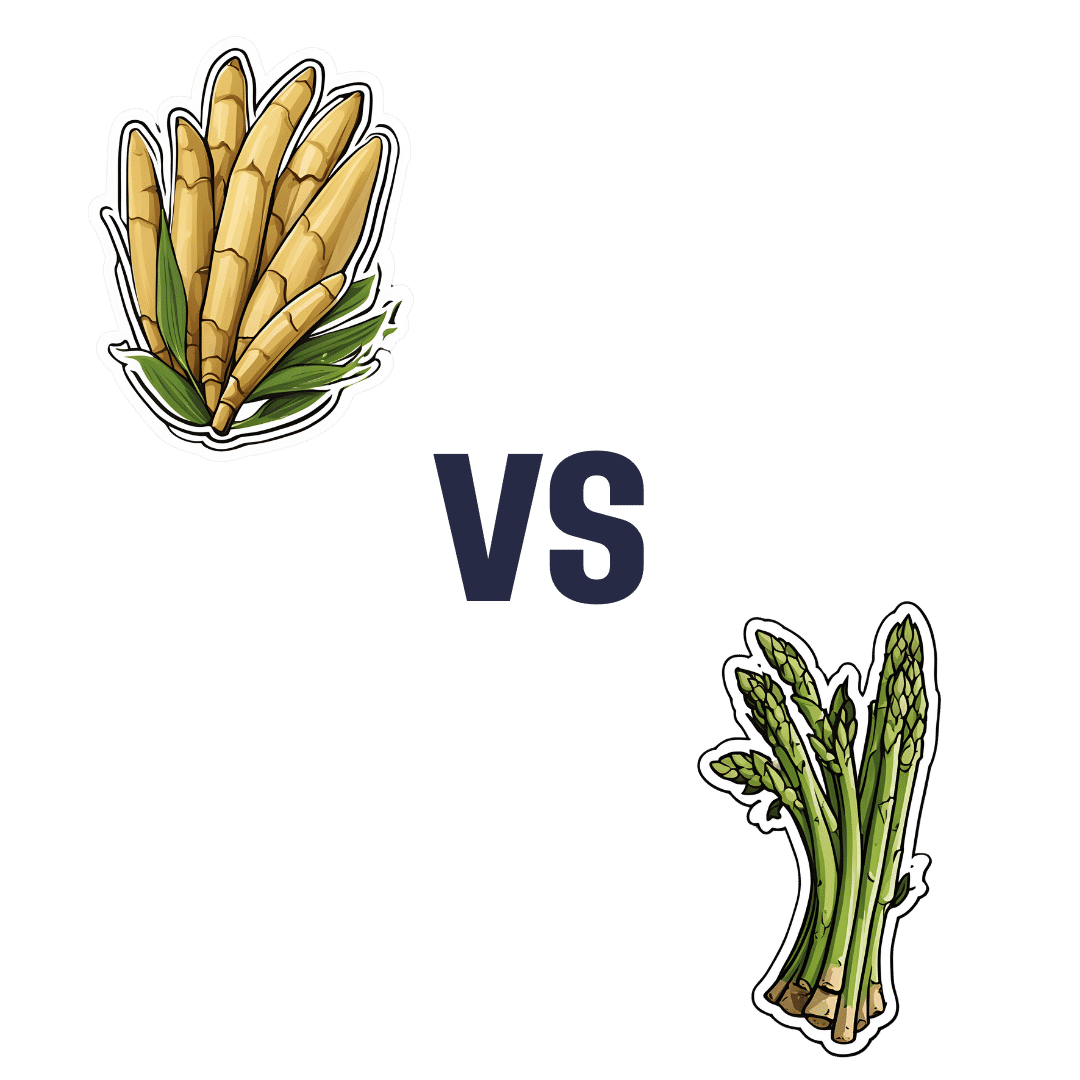

Bamboo Shoots vs Asparagus – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing bamboo shoots to asparagus, we picked the asparagus.

Why?

Both are great! But asparagus does distinguish itself on nutritional density.

In terms of macros, bamboo starts strong with more protein and fiber, but it’s not a huge amount more; the margins of difference are quite small.

In the category of vitamins, asparagus wins easily with more of vitamins A, B2, B3, B5, B9, C, E, K, and choline. In contrast, bamboo boasts only more vitamin B6. A clear win for asparagus.

The minerals line-up is closer; asparagus has more calcium, iron, magnesium, and selenium, while bamboo shoots have more manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc. That’s a 4:4 tie, but asparagus’s margins of difference are larger, and if we need a further tiebreaker, bamboo also contains more sodium, which most people in the industrialized world could do with less of rather than more. So, a small win for asparagus.

In short, adding up the sections… Bamboo shoots, but asparagus scores, and wins the day. Enjoy both, of course, but if making a pick, then asparagus has more bang-for-buck.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Asparagus vs Eggplant – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Give Us This Day Our Daily Dozen

This is Dr. Michael Greger. He’s a physician-turned-author-educator, and we’ve featured him and his work occasionally over the past year or so:

- Brain Food? The Eyes Have It! ← this is about dark leafy greens, lutein, & avoiding Alzheimer’s

- Twenty-One, No Wait, Twenty Tweaks For Better Health ← he says 21, but we say one of them is very skippable. Check it out and decide what you think!

- Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight ← his top well-evidenced interventions specifically for slowing aging

But what we’ve not covered, astonishingly, is one of the things for which he’s most famous, which is…

Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen

Based on the research in the very information-dense tome that his his magnum opus How Not To Die (while it doesn’t confer immortality, it does help avoid the most common causes of death), Dr. Greger recommends that we take care to enjoy each of the following things per day:

Beans

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: ½ cup cooked beans, ¼ cup hummus

Greens

- Servings: 2 per day

- Examples: 1 cup raw, ½ cup cooked

Cruciferous vegetables

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ½ cup chopped, 1 tablespoon horseradish

Other vegetables

- Servings: 2 per day

- Examples: ½ cup non-leafy vegetables

Whole grains

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: ½ cup hot cereal, 1 slice of bread

Berries

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ½ cup fresh or frozen, ¼ cup dried

Other fruits

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: 1 medium fruit, ¼ cup dried fruit

Flaxseed

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: 1 tablespoon ground

Nuts & (other) seeds

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ¼ cup nuts, 2 tablespoons nut butter

Herbs & spices

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ¼ teaspoon turmeric

Hydrating drinks

- Servings: 60 oz per day

- Examples: Water, green tea, hibiscus tea

Exercise

- Servings: Once per day

- Examples: 90 minutes moderate or 40 minutes vigorous

Superficially it seems an interesting choice to, after listing 11 foods and drinks, have the 12th item as exercise but not add a 13th one of sleep—but perhaps he quite reasonably expects that people get a dose of sleep with more consistency than people get a dose of exercise. After all, exercise is mostly optional, whereas if we try to skip sleep for too long, our body will force the matter for us.

Further 10almonds notes:

- We’d consider chia superior to flax, but you do you. Flax is a fine choice also.

- We recommend trying to get each of these top 5 most health-giving spices in daily if you can.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Truth About Chocolate & Skin Health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝What’s the science on chocolate and acne? Asking for a family member❞

The science is: these two things are broadly unrelated to each other.

There was a very illustrative study done specifically for this, though!

❝65 subjects with moderate acne ate either a bar containing ten times the amount of chocolate in a typical bar, or an identical-appearing bar which contained no chocolate. Counting of all the lesions on one side of the face before and after each ingestion period indicated no difference between the bars.

Five normal subjects ingested two enriched chocolate bars daily for one month; this represented a daily addition of the diet of 1,200 calories, of which about half was vegetable fat. This excessive intake of chocolate and fat did not alter the composition or output of sebum.

A review of studies purporting to show that diets high in carbohydrate or fat stimulate sebaceous secretion and adversely affect acne vulgaris indicates that these claims are unproved.❞

Source: Effect of Chocolate on Acne Vulgaris

As for what might help against acne more than needlessly abstaining from chocolate:

Why Do We Have Pores, And Could We Not?

…as well as:

Of Brains & Breakouts: The Neuroscience Of Your Skin

And here are some other articles that might interest you about chocolate:

- Chocolate & Health: Fact or Fiction?

- The “Love Drug”: Get PEA-Brained!

- Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

Enjoy! And while we have your attention… Would you like this section to be bigger? If so, send us more questions!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Alzheimer’s may have once spread from person to person, but the risk of that happening today is incredibly low

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

An article published this week in the prestigious journal Nature Medicine documents what is believed to be the first evidence that Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted from person to person.

The finding arose from long-term follow up of patients who received human growth hormone (hGH) that was taken from brain tissue of deceased donors.

Preparations of donated hGH were used in medicine to treat a variety of conditions from 1959 onwards – including in Australia from the mid 60s.

The practice stopped in 1985 when it was discovered around 200 patients worldwide who had received these donations went on to develop Creuztfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which causes a rapidly progressive dementia. This is an otherwise extremely rare condition, affecting roughly one person in a million.

What’s CJD got to do with Alzehimer’s?

CJD is caused by prions: infective particles that are neither bacterial or viral, but consist of abnormally folded proteins that can be transmitted from cell to cell.

Other prion diseases include kuru, a dementia seen in New Guinea tribespeople caused by eating human tissue, scrapie (a disease of sheep) and variant CJD or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, otherwise known as mad cow disease. This raised public health concerns over the eating of beef products in the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

Human growth hormone used to come from donated organs

Human growth hormone (hGH) is produced in the brain by the pituitary gland. Treatments were originally prepared from purified human pituitary tissue.

But because the amount of hGH contained in a single gland is extremely small, any single dose given to any one patient could contain material from around 16,000 donated glands.

An average course of hGH treatment lasts around four years, so the chances of receiving contaminated material – even for a very rare condition such as CJD – became quite high for such people.

hGH is now manufactured synthetically in a laboratory, rather than from human tissue. So this particular mode of CJD transmission is no longer a risk.

Human growth hormone is now produced in a lab.

National Cancer Institute/UnsplashWhat are the latest findings about Alzheimer’s disease?

The Nature Medicine paper provides the first evidence that transmission of Alzheimer’s disease can occur via human-to-human transmission.

The authors examined the outcomes of people who received donated hGH until 1985. They found five such recipients had developed early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

They considered other explanations for the findings but concluded donated hGH was the likely cause.

Given Alzheimer’s disease is a much more common illness than CJD, the authors presume those who received donated hGH before 1985 may be at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is caused by presence of two abnormally folded proteins: amyloid and tau. There is increasing evidence these proteins spread in the brain in a similar way to prion diseases. So the mode of transmission the authors propose is certainly plausible.

However, given the amyloid protein deposits in the brain at least 20 years before clinical Alzheimer’s disease develops, there is likely to be a considerable time lag before cases that might arise from the receipt of donated hGH become evident.

When was this process used in Australia?

In Australia, donated pituitary material was used from 1967 to 1985 to treat people with short stature and infertility.

More than 2,000 people received such treatment. Four developed CJD, the last case identified in 1991. All four cases were likely linked to a single contaminated batch.

The risks of any other cases of CJD developing now in pituitary material recipients, so long after the occurrence of the last identified case in Australia, are considered to be incredibly small.

Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (defined as occurring before the age of 65) is uncommon, accounting for around 5% of all cases. Below the age of 50 it’s rare and likely to have a genetic contribution.

Early onset Alzheimer’s means it occurs before age 65.

perfectlab/ShutterstockThe risk is very low – and you can’t ‘catch’ it like a virus

The Nature Medicine paper identified five cases which were diagnosed in people aged 38 to 55. This is more than could be expected by chance, but still very low in comparison to the total number of patients treated worldwide.

Although the long “incubation period” of Alzheimer’s disease may mean more similar cases may be identified in the future, the absolute risk remains very low. The main scientific interest of the article lies in the fact it’s first to demonstrate that Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted from person to person in a similar way to prion diseases, rather than in any public health risk.

The authors were keen to emphasise, as I will, that Alzheimer’s cannot be contracted via contact with or providing care to people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Steve Macfarlane, Head of Clinical Services, Dementia Support Australia, & Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Eat More, Live Well – by Dr. Megan Rossi

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Often, eating healthily can feel restrictive. Don’t eat this, skip that, eliminate the other. Where is the joy?

Dr. Megan Rossi brings a scientific angle on positive dieting, that is to say, looking at what to add, rather than what to subtract. Now, the idea isn’t to have sugar-laden chocolate cake with berries on top and call it a net positive because of the berries, though. Rather, Dr. Rossi lays out how to include as many diverse vegetables and fruits as possible, with tasty recipes so that we’re too busy with those to crave junk food.

Speaking of recipes, there are 80, and they are easy to follow. She describes them as “plant-based”, and by this what she really means is “plant-centric” or such; she does include the use of some animal products.

This is important to note, because general convention is to use “plant-based” to mean functionally vegan, but being about the food rather than the ideology; a relevant distinction in both society and science. In the case of this book, it’s neither, but it is very healthy.

Bottom line: if you’d like to introduce more healthy diversity to your diet, rather than eating the same three fruits and five vegetables, but you’re not sure how, this book will get you where you need to be.

Click here to check out Eat More, Live Well, and diversify your diet!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: