HBD: The Human Being Diet – by Petronella Ravenshear

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We don’t often review diet books, so why did this one catch our attention? The answer lies in its comprehensive nature without being excessively long and complex.

Ravenshear (a nutritionist) brings a focus on metabolic balance, and what will and won’t work for keeping it healthy.

The first part of the book is mostly informational; covering such things as blood sugar balance, gut health, hormones, and circadian rhythm considerations, amongst others.

The second, larger part of the book is mostly instructional; do this and that, don’t do the other, guidelines on quantities and timings, and what things may be different for some people, and what to do about those.

The style is conversational and light, but well-grounded in good science.

Bottom line: if you’d like a “one-stop shop” for giving your diet an overhaul, this book is a fine choice.

Click here to check out the Human Being Diet, and enjoy the best of health!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Are Brain Chips Safe?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ready For Cyborgization?

In yesterday’s newsletter, we asked you for your views on Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), such as the Utah Array and Neuralink’s chips on/in brains that allow direct communication between brains and computers, so that (for example) a paralysed person can use a device to communicate, or manipulate a prosthetic limb or two.

We didn’t get as many votes as usual; it’s possible that yesterday’s newsletter ended up in a lot of spam filters due to repeated use of a word in “extra ______ olive oil” in its main feature!

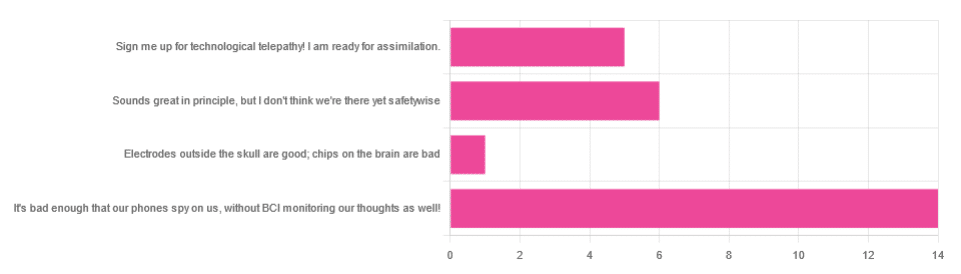

However, of the answers we did get…

- About 54% said “It’s bad enough that our phones spy on us, without BCI monitoring our thoughts as well!”

- About 23% said “Sounds great in principle, but I don’t think we’re there yet safetywise”

- About 19% said “Sign me up for technological telepathy! I am ready for assimilation”

- One (1) person said “Electrode outside the skull are good; chips on the brain are bad”

But what does the science say?

We’re not there yet safetywise: True or False?

True, in our opinion, when it comes to the latest implants, anyway. While it’s very difficult to prove a negative (it could be that everything goes perfectly in human trials), “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, and so far this seems to be lacking.

The stage before human trials is usually animal trials, starting with small creatures and working up to non-human primates if appropriate, before finally humans.

- Good news: the latest hot-topic BCI device (Neuralink) was tested on animals!

- Bad news: to say it did not go well would be an understatement

The Gruesome Story of How Neuralink’s Monkeys Actually Died

The above is a Wired article, and we tend to go for more objective sources, however we chose this one because it links to very many objective sources, including an open letter from the Physicians’ Committee for Responsible Medicine, which basically confirms everything in the Wired article. There are lots of links to primary (medical and legal) sources, too.

Electrodes outside the skull are good; chips on/in the brain are bad: True or False?

True or False depending on how they’re done. The Utah Array (an older BCI implant, now 20 years old, though it’s been updated many times since) has had a good safety record, after being used by a few dozen people with paralysis to control devices:

How the Utah Array is advancing BCI science

The Utah Array works on the same general principle as Neuralink, but the mechanics of its implementation are very different:

- The Utah Array involves a tiny bundle of microelectrodes (held together by a rigid structure that looks a bit like a nanoscale hairbrush) put in place by a brain surgeon, and that’s that.

- The Neuralink has a dynamic web of electrodes, implanted by a little robot that acts like a tiny sewing machine to implant many polymer threads, each containing its own a bunch of electrodes.

In theory, the latter is much more advanced. In practice, so far, the former has a much better safety record.

I am right to be a little worried about giving companies access to my brain: True or False?

True or False, depending on the nature of your concern.

For privacy: current BCI devices have quite simple switches operated consciously by the user. So while technically any such device that then runs its data through Bluetooth or WiFi could be hacked, this risk is no greater than using a wireless mouse and/or keyboard, because it has access to about the same amount of information.

For safety: yes, probably there is cause to be worried. Likely the first waves of commercial users of any given BCI device will be severely disabled people who are more likely to waive their rights in the hope of a life-changing assistance device, and likely some of those will suffer if things go wrong.

Which on the one hand, is their gamble to make. And on the other hand, makes rushing to human trials, for companies that do that, a little more predatory.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Gut-Healthy Sunset Soup

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

So-called for its gut-healthy ingredients, and its flavor profile being from the Maghreb (“Sunset”) region, the western half of the N. African coast.

You will need

- 1 can chickpeas (do not drain)

- 1 cup low-sodium vegetable stock

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 1 carrot, finely chopped

- 2 tbsp sauerkraut, drained and chopped (yes, it is already chopped, but we want it chopped smaller so it can disperse evenly in the soup)

- 2 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tbsp harissa paste (adjust per your heat preference)

- 1 tbsp ras el-hanout

- ¼ bulb garlic, crushed

- Juice of ½ lemon

- ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Optional: herb garnish; we recommend cilantro or flat-leaf parsley

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat a little oil in a sauté pan or similar (something suitable for combination cooking, as we’ll be frying first and then adding liquids), and fry the onion and carrot until the onion is soft and translucent; about 5 minutes.

2) Stir in the garlic, tomato paste, harissa paste, and ras el-hanout, and fry for a further 1 minute.

3) Add the remaining ingredients* except the lemon juice. Bring to the boil and then simmer for 5 minutes.

*So yes, this includes adding the “chickpea water” also called “aquafaba”; it adds flavor and also gut-healthy fiber in the form of oligosaccharides and resistant starches, which your gut microbiota can use to make short-chain fatty acids, which improve immune function and benefit the health in more ways than we can reasonably mention as a by-the-way in a recipe.

4) Stir in the lemon juice, and serve, adding a herb garnish if you wish.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← today’s recipe scored 5/5 of these, plus quite a few more! Remember that ras el-hanout is a spice blend, so if you’re thinking “wait, where’s the…?” then it’s in the ras el-hanout 😉

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More ← not to be underestimated!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

How To Unchoke Yourself If You Are Dying Alone

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The first things that most people think of, won’t work. This firefighter advises on how to actually do it:

Steps to take

Zero’th step: he doesn’t mention this, but try coughing first. You might think coughing will be a natural reaction anyway, but that tends only to happen automatically with small partial obstructions, not a complete blockage. Either way, try to cough forcefully to see if it dislodges whatever you’re choking on. If that doesn’t work…

Firstly: don’t rely on calling for help if you’re alone and cannot speak; you’re unlikely to be able to communicate and you will just waste time (when you don’t have time to waste). Even if you call emergency services and they trace your location, chances are that, at most, a cop car will show up some hours later to see what it was about. They will not dispatch an ambulance on the strength of “someone called and said nothing”.

Secondly, it is probable that will not be able to perform an abdominal thrust (also called Heimlich maneuvre in the US) on yourself the way you could on another person, and hitting your chest with your hand will produce insufficient force even if you’re quite strong. Nor are you likely to be able to slap yourself on the back to way you might another person.

Instead, he advises:

- Find a sturdy object: use a chair, table, countertop, or another firm surface that has an edge.

- Use gravity to perform self-Heimlich: position yourself with the edge of the object just below your sternum (he says ribcage, but the visuals show he clearly means the bottom of the sternum, where the diaphragm is, not the lower ribs). Fall onto the object forcefully to create pressure and dislodge the obstruction. This will not be fun.

- If it doesn’t work indoors: move to a visible outdoor location like your yard or a neighbor’s lawn. Falling visibly on the ground will likely alert someone to call for help.

While doing the above, remain as calm as possible, as this will not only increase the length of time you have before passing out, but will also help avoid your throat muscles tightening even more, worsening the choking.

After doing the above, seek medical attention now that you can communicate; you’ve probably broken some ribs and you might have organ damage.

For more on all this plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

How To Survive A Heart Attack When You’re Alone ← very different advice for this scenario!

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How To Avoid Age-Related Macular Degeneration

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Avoiding Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Eye problems can strike at any age, but as we get older, it becomes a lot more likely. In particular, age-related macular degeneration is, as the name suggests, an age-bound disease.

Is there no escaping it, then?

The risk factors for age-related macular degeneration are as follows:

- Being over the age of 55 (can’t do much about this one)

- Being over the age of 65 (risk climbs sharply now)

- Having a genetic predisposition (can’t do much about this one)

- Having high cholesterol (this one we can tackle)

- Having cardiovascular disease (this one we can tackle)

- Smoking (so, just don’t)

Genes predispose; they don’t predetermine. Or to put it another way: genes load the gun, but lifestyle pulls the trigger.

Preventative interventions against age-related macular degeneration

Prevention is better than a cure in general, and this especially goes for things like age-related macular degeneration, because the most common form of it has no known cure.

So first, look after your heart (because your heart feeds your eyes).

See also: The Mediterranean Diet

Next, eat to feed your eyes specifically. There’s a lot of research to show that lutein helps avoid age-related diseases in the eyes and the rest of the brain, too:

See also: Brain Food? The Eyes Have It

Do supplements help?

They can! There was a multiple-part landmark study by the National Eye Institute, a formula was developed that reduced the 5-year risk of intermediate disease progressing to late disease by 25–30%. It also reduced the risk of vision loss by 19%.

You can read about both parts of the study here:

Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS/AREDS2): major findings

As you can see, an improvement was made between the initial study and the second one, by replacing beta-carotene with lutein and zeaxanthin.

The AREDS2 formula contains:

- 500 mg vitamin C

- 180 mg vitamin E

- 80 mg zinc

- 10 mg lutein

- 2 mg copper

You can learn more about these supplements, and where to get them, here on the NEI’s corner of the official NIH website:

AREDS 2 Supplements for Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Take care of yourself!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Brazil Nuts vs Pecans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing Brazil nuts to pecans, we picked the pecans.

Why?

In terms of macros, Brazil nuts have more protein while pecans have more fiber. Both of these nuts are equally fatty, though Brazil nuts have much more saturated fat per 100g, which still isn’t terrible, but it does make pecans’ profile (mostly monounsaturated with some polyunsaturated) the healthier. They’re about equal in carbs. All in all, a win for pecans here.

In the category of vitamins, Brazil nuts have more vitamin E, while pecans have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, C, K, and choline. An easy win for pecans.

The category of minerals is an interesting one. Brazil nuts have more calcium, copper, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while pecans have more iron, manganese, and zinc. Before we crown Brazil nuts with the win in this category, though, let’s take a closer look at those selenium levels:

- A cup of pecans contains 21% of the RDA of selenium. Your hair will be luscious and shiny.

- A cup of Brazil nuts contains 10,456% of the RDA of selenium. This is way past the point of selenium toxicity, and your (luscious, shiny) hair will fall out.

For this reason, it’s recommended to eat no more than 3–4 Brazil nuts per day.

We consider that a point against Brazil nuts.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for pecans; of course, enjoy either or both, just be sure to practise moderation when it comes to the Brazil nuts!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Chetna’s Healthy Indian – by Chetna Makan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Indian food is wonderful—a subjective opinion perhaps, but a popular view, and one this reviewer certainly shares. And of course, cooking with plenty of vegetables and spices is a great way to get a lot of health benefits.

There are usually downsides though, such as that in a lot of Indian cookbooks, every second thing is deep-fried, and what’s not deep-fried contains an entire day or more’s saturated fat content in ghee, and a lot of sides have more than their fair share of sugar.

This book fixes all that, by offering 80 recipes that prioritize health without sacrificing flavor.

The recipes are, as the title suggests, vegetarian, though many are not vegan (yogurt and cheese featuring in many recipes). That said, even if you are vegan, it’s pretty easy to veganize those with the obvious plant-based substitutions. If you have soy yogurt and can whip up vegan paneer yourself (here’s our own recipe for that), you’re pretty much sorted.

The cookbook strikes a good balance of being neither complicated nor “did we really need a recipe for this?” basic, and delivers value in all of its recipes. The ingredients, often a worry for many Westerners, should be easily found if you have a well-stocked supermarket near you; there’s nothing obscure here.

Bottom line: if you’d like to cook more Indian food and want your food to be exciting without also making your blood pressure exciting, then this is an excellent book for keeping you well-nourished, body and soul.

Click here to check out Chetna’s Healthy Indian, and spice up your culinary repertoire!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: