A Guide to the Good Life – by Dr. William Irvine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Living well” is a surprisingly underrated part of wellness. We spend much of our lives in turmoil. Some of us, windswept and battered by the storms of life; others, up in quietly crumbling towers, seemingly “great” but definitely not feeling it. Diet and exercise etc will only get us so far. What else, then, can we do?

For Dr. Irvine, the key lies in two main things:

- Deciding how we intend to live our life (and doing so)

- Remaining tranquil in the face of external stressors

In Japanese terms, these things can be seen in ikigai and zen, respectively. This book puts them in Western terms, specifically, that of Stoic philosophy. But the goals and methods are very similar.

Far from being an abstract tome of wishy-washy philosophy, this book offers down-to-earth practical exercises and easily applicable advice. There was even an exercise that was new to this reviewer who has been reading such things for decades.

The writing style is also, true to Stoic principles, unpretentious and simple. This is an easy book to read, while being nonethless very engaging from start to finish—and thereafter!

Bottom line: so far as we know, we only get one shot at life, so we might as well make it a good one. Applying the ideas found in this book can help any reader to live better, and take more joy in it along the way.

Click here to check out a Guide to the Good Life, and live your best!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How To Nap Like A Pro (No More “Sleep Hangovers”!)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How To Be An Expert Nap-Artist

There’s a lot of science to say that napping can bring us health benefits—but mistiming it can just make us more tired. So, how to get some refreshing shut-eye, without ending up with a case of the midday melatonin blues?

First, why do we want to nap?

Well, maybe we’re just tired, but there are specific benefits even if we’re not. For example:

- Increased alertness

- Helps with learning

- Improved memory

- Boost to immunity

- Enhance athletic performance

What can go wrong?

There are two main things that can go wrong, physiologically speaking:

- We can overdo it, and not sleep well at night

- We can awake groggy and confused and tired

The first is self-explanatory—it messes with the circadian rhythm. For this reason, we should not sleep more than 90 minutes during the day. If that seems like a lot, and maybe you’ve heard that we shouldn’t sleep more than half an hour, there is science here, so read on…

The second is a matter of sleep cycles. Our brain naturally organizes our sleep into multiples of 20-minute segments, with a slight break of a few minutes between each. Consequently, naps should be:

- 25ish minutes

- 40–45 minutes

- 90ish minutes

If you wake up mid-cycle—for example, because your alarm went off, or someone disturbed you, or even because you needed to pee, you will be groggy, disoriented, and exhausted.

For this reason, a nap of one hour (a common choice, since people like “round” numbers) is a recipe for disaster, and will only work if you take 15 minutes to fall asleep. In which case, it’d really be a nap of 45 minutes, made up of two 20-minute sleep cycles.

Some interruptions are better/worse than others

If you’re in light or REM sleep, a disruption will leave you not very refreshed, but not wiped out either. And as a bonus, if you’re interrupted during a REM cycle, you’re more likely to remember your dreams.

If you’re in deep sleep, a disruption will leave you with what feels like an incredible hangover, minus the headache, and you’ll be far more tired than you were before you started the nap.

The best way to nap

Taking these factors into account, one of the “safest” ways to nap is to set your alarm for the top end of the time-bracket above the one you actually want to nap for (e.g., if you want to nap for 25ish minutes, set your alarm for 45).

Unless you’re very sleep-deprived, you’ll probably wake up briefly after 20–25 minutes of sleep. This may seem like nearer 30 minutes, if it took you some minutes to fall asleep!

If you don’t wake up then, or otherwise fail to get up, your alarm will catch you later at what will hopefully be between your next sleep cycles, or at the very least not right in the middle of one.

When you wake up from a nap before your alarm, get up. This is not the time for “5 more minutes” because “5 more minutes” will never, ever, be refreshing.

Rest well!

Share This Post

-

How to Permanently Loosen a Tight Psoas

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Is Your Psoas?

Your psoas is a deep muscle in your lower back and hip area that connects your spine to your thigh bone. It helps you bend your hips and spine, making it a hip flexor.

In today’s video, Your Wellness Nerd (the YouTube channel behind the video below) has revealed some great tips on loosening said tight hip flexors!

How to loosen them

First off, the big reveal…your tight psoas is likely stemming from an overlooked cause: your lower back! The video kicks off with a simple technique to loosen up that stiff area in your lower back. All you need is a foam roller.

But, before diving into the exercises, it’s essential to gauge your current flexibility. A basic hip flexor stretch serves as a pre-test.

Note: the goal here isn’t to stretch, but rather to feel how tight you are.

After testing, it’s time to roll…literally. Working through the lower back, use your roller or tennis ball to any find stiff spots and loosen them out; those spots are likely increasing the tension on your psoas.

After some rolling, retest with the hip flexor stretch. Chances are, you’ll feel more mobility and less tightness right away.

Note: this video focuses on chronic psoas issues. If you have sore psoas from a muscular workout, you may want to read our piece on speeding up muscle recovery.

Is That All?

But wait, there’s more! The video also covers two more exercises specifically targeting the psoas. This one’s hard to describe, so we recommend watching the video. However, to provide an overview, you’re doing the “classic couch stretch”, but with a few alterations.

Next, the tennis ball technique zeroes in on specific tight spots in the psoas. By lying on the ball and adjusting its position around the hip area, you can likely release some deeply held tension.

Additionally, some of our readers advocate for acupuncture for psoas relief – we’ve done an acupuncture myth-busting article here for reference.

Other Sources

If you’re looking for some more in-depth guides on stretching your psoas, and your body in general, we’ve made a range of 1-minute summaries of books that specifically target stretching:

- 11 Minutes to Pain-Free Hips (perfect for psoas muscles)

- Stretching Scientifically

- Stretching & Mobility

- Stretching to Stay Young

The final takeaway? If you’re constantly battling tight psoas muscles despite trying different exercises and stretches, it might be time to look at your lower back and your daily habits. This video isn’t just a band-aid fix; it’s about addressing the root cause for long-term relief:

How did you find that video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

CBD Against Diabetes!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝CBD for diabetes! I’ve taken CBD for body pain. Did no good. Didn’t pay attention as to diabetes. I’m type 1 for 62 years. Any ideas?❞

Thanks for asking! First up, for reference, here’s our previous main feature on the topic of CBD:

CBD Oil: What Does The Science Say?

There, we touched on CBD’s effects re diabetes:

in mice / in vitro / in humans

In summary, according to the above studies, it…

- lowered incidence of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. By this they mean that pancreatic function improved (reduced insulitis and reduced inflammatory Th1-associated cytokine production). Obviously this has strong implications for Type 1 Diabetes in humans—but so far, just that, implications (because you are not a mouse).

- attenuated high glucose-induced endothelial cell inflammatory response and barrier disruption. Again, this is promising, but it was an in vitro study in very controlled lab conditions, and sometimes “what happens in the Petri dish, stays in the Petri dish”—in order words, these results may or may not translate to actual living humans.

- Improved insulin response ← is the main take-away that we got from reading through their numerical results, since there was no convenient conclusion given. Superficially, this may be of more interest to those with type 2 diabetes, but then again, if you have T1D and then acquire insulin resistance on top of that, you stand a good chance of dying on account of your exogenous insulin no longer working. In the case of T2D, “the pancreas will provide” (more or less), T1D, not so much.

So, what else is there out there?

The American Diabetes Association does not give a glowing review:

❝There’s a lot of hype surrounding CBD oil and diabetes. There is no noticeable effect on blood glucose (blood sugar) or insulin levels in people with type 2 diabetes. Researchers continue to study the effects of CBD on diabetes in animal studies. ❞

~ American Diabetes Association

Source: ADA | CBD & Diabetes

Of course, that’s type 2, but most research out there is for type 2, or else have been in vitro or rodent studies (and not many of those, at that).

Here’s a relatively more recent study that echoes the results of the previous mouse study we mentioned; it found:

❝CBD-treated non-obese diabetic mice developed T1D later and showed significantly reduced leukocyte activation and increased FCD in the pancreatic microcirculation.

Conclusions: Experimental CBD treatment reduced markers of inflammation in the microcirculation of the pancreas studied by intravital microscopy. ❞

~ Dr. Christian Lehmann et al.

Read more: Experimental cannabidiol treatment reduces early pancreatic inflammation in type 1 diabetes

…and here’s a 2020 study (so, more recent again) that was this time rats, and/but still more promising, insofar as it was with rats that had full-blown T1D already:

Read in full: Two-weeks treatment with cannabidiol improves biophysical and behavioral deficits associated with experimental type-1 diabetes

Finally, a paper in July 2023 (so, since our previous article about CBD), looked at the benefits of CBD against diabetes-related complications (so, applicable to most people with any kind of diabetes), and concluded:

❝CBDis of great value in the treatment of diabetes and its complications. CBD can improve pancreatic islet function, reduce pancreatic inflammation and improve insulin resistance. For diabetic complications, CBD not only has a preventive effect but also has a therapeutic value for existing diabetic complications and improves the function of target organs❞

…before continuing:

❝However, the safety and effectiveness of CBD are still needed to prove. It should be acknowledged that the clinical application of CBD in the treatment of diabetes and its complications has a long way to go.

The dissecting of the pharmacology and therapeutic role of CBD in diabetes would guide the future development of CBD-based therapeutics for treating diabetes and diabetic complications❞

~ Ibid.

Now, the first part of that is standard ass-covering, and the second part of that is standard “please fund more studies please”. Nevertheless, we must also not fail to take heed—little is guaranteed, especially when it comes to an area of research where the science is still very young.

In summary…

It seems well worth a try, and with ostensibly nothing to lose except the financial cost of the CBD.

If you do, you might want to keep careful track of a) your usual diabetes metrics (blood sugar levels before and after meals, insulin taken), and b) when you took CBD, what dose, etc, so you can do some citizen science here.

Lastly: please remember our standard disclaimer; we are not doctors, let alone your doctors, so please do check with your endocrinologist before undertaking any such changes!

Want to read more?

You might like our previous main feature:

How To Prevent And Reverse Type 2 Diabetes ← obviously this will not prevent or reverse Type 1 Diabetes, but avoiding insulin resistance is good in any case!

If you’re not diabetic and you’ve perhaps been confused throughout this article, then firstly thank you for your patience, and secondly you might like this quick primer:

The Sweet Truth About Diabetes: Debunking Diabetes Myths! ← this gives a simplified but fair overview of types 1 & 2

(for space, we didn’t cover the much less common types 3 & 4; perhaps another time we will)

Meanwhile, take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Support For Long COVID & Chronic Fatigue

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Long COVID and Chronic Fatigue

Getting COVID-19 can be very physically draining, so it’s no surprise that getting Long COVID can (and usually does) result in chronic fatigue.

But, what does this mean and what can we do about it?

What makes Long COVID “long”

Long COVID is generally defined as COVID-19 whose symptoms last longer than 28 days, but in reality the symptoms not only tend to last for much longer than that, but also, they can be quite distinct.

Here’s a large (3,762 participants) study of Long COVID, which looked at 203 symptoms:

Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact

Three symptoms stood at out as most prevalent:

- Chronic fatigue (CFS)

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Post-exertional malaise (PEM)

The latter means “the symptoms get worse following physical or mental exertion”.

CFS, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, is also called Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME).

What can be done about it?

The main “thing that people do about it” is to reduce their workload to what they can do, but this is not viable for everyone. Note that work doesn’t just mean “one’s profession”, but anything that requires physical or mental energy, including:

- Childcare

- Housework

- Errand-running

- Personal hygiene/maintenance

For many, this means having to get someone else to do the things—either with support of family and friends, or by hiring help. For many who don’t have those safety nets available, this means things simply not getting done.

That seems bleak; isn’t there anything more we can do?

Doctors’ recommendations are chiefly “wait it out and hope for the best”, which is not encouraging. Some people do recover from Long COVID; for others, it so far appears it might be lifelong. We just don’t know yet.

Doctors also recommend to journal, not for the usual mental health benefits, but because that is data collection. Patients who journal about their symptoms and then discuss those symptoms with their doctors, are contributing to the “big picture” of what Long COVID and its associated ME/CFS look like.

You may notice that that’s not so much saying what doctors can do for you, so much as what you can do for doctors (and in the big picture, eventually help them help people, which might include you).

So, is there any support for individuals with Long COVID ME/CFS?

Medically, no. Not that we could find.

However! Socially, there are grassroots support networks, that may be able to offer direct assistance, or at least point individuals to useful local resources.

Grassroots initiatives include Long COVID SOS and the Patient-Led Research Collaborative.

The patient-led organization Body Politic also used to have such a group, until it shut down due to lack of funding, but they do still have a good resource list:

Click here to check out the Body Politic resource list (it has eight more specific resources)

Stay strong!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

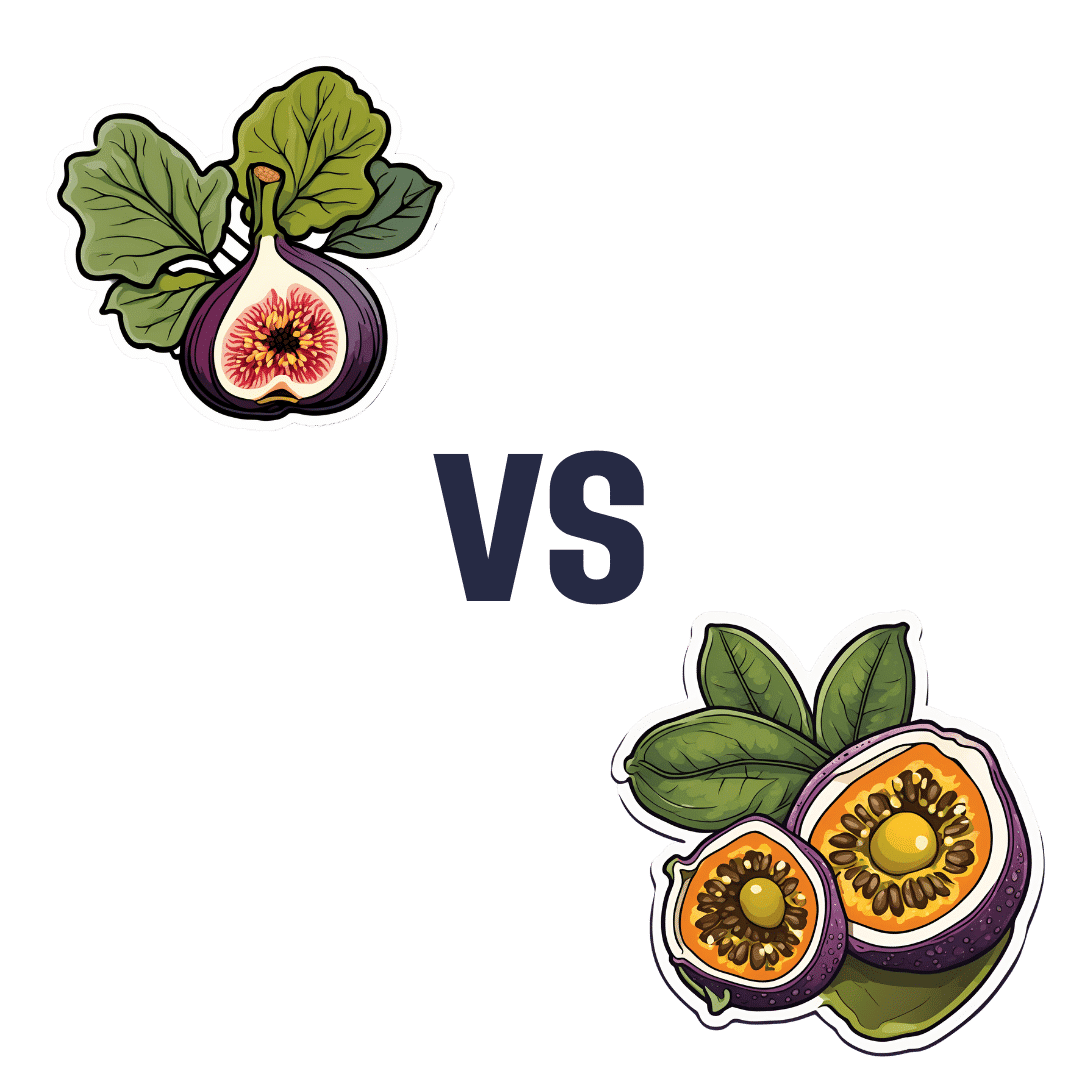

Figs vs Passion Fruit – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing figs to passion fruit, we picked the passion fruit.

Why?

Both are top-tier fruits! But the passion fruit is just that bit more passionate about delivering healthy nutrients:

In terms of macros, passion fruit has slightly more carbs, notably more protein, and a lot more fiber, giving it the win in this category.

In the category of vitamins, figs have more of vitamins B1, B5, B6, E, and K, while passion fruit has more of vitamins A, B2, B3, B9, C, and choline, making for a marginal win by the numbers for passion fruit here.

When it comes to minerals, figs have more calcium, manganese, and zinc, while passion fruit has more copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium. A clearer win for passion fruit this time.

Adding up the sections makes for an easy overall win for passion fruit, but again, figs are really a top-tier fruit too; passion fruit just beats them! By all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer ← figs have antitumor effects specifically, while removing carcinogens too, and additionally sensitizing cancer cells to light therapy

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Crispy Tofu Pad Thai

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Easy to make, delicious to enjoy, and packed with phytonutrients, this dish is a great one to add to your repertoire:

You will need

- 10 oz ready-to-wok rice noodles, or 6 oz dry

- 5 oz silken tofu

- 5 oz firm or extra firm tofu, cut into small cubes

- 1 oz arrowroot (or cornstarch if you don’t have arrowroot)

- 4 scallions, sliced

- ¼ bulb garlic, finely chopped

- 1″ piece fresh ginger, grated

- 1 red chili, chopped (multiply per your heat preferences)

- 1 red bell pepper, deseeded and thinly sliced

- 4 oz bok choi, thinly sliced

- 4 oz mung bean sprouts

- 1 tbsp tamari (or other, but tamari is traditional) soy sauce

- 1 tbsp sweet chili sauce

- Juice of ½ lime

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Avocado oil, or your preferred oil for stir-frying

- To serve: lime wedges

- Optional garnish: crushed roasted peanuts (if allergic, substitute sesame seeds; peanuts are simply traditional, that’s all)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Scramble the silken tofu. For guidance and also additional seasoning pointers, see our Tasty Tofu Scramble recipe, but omit the thyme.

2) Cook the noodles if necessary (i.e. if they are the dry type and need boiling, as opposed to “ready-to-wok” noodles that don’t), drain, and set aside.

4) Prepare the tofu cubes: if the tofu cubes are dry to the touch, toss them gently in a little oil to coat. If they’re wet to the touch, no need. Dust the tofu cubes with the arrowroot and MSG/salt; you can do this in a bowl, tossing gently to distribute the coating evenly.

4) Heat some oil in a wok over a high heat, and fry the tofu on each side until golden and crispy all over, and set aside.

5) Stir-fry the scallions, garlic, ginger, chili, and bell pepper for about 2 minutes.

6) Add the bean sprouts and bok choi, and keep stir-frying for another 2 minutes.

7) Add everything that’s not already in the pan except the lime wedges and peanuts (i.e., add the things you set aside, plus the remaining as-yet-untouched ingredients) and stir-fry for a further 2 minutes.

8) Serve hot, garnished with the crushed peanuts if using, and with the lime wedges on the side:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Sprout Your Seeds, Grains, Beans, Etc

- Which Bell Peppers To Pick? A Spectrum Of Specialties

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: