4 things ancient Greeks and Romans got right about mental health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

According to the World Health Organization, about 280 million people worldwide have depression and about one billion have a mental health problem of any kind.

People living in the ancient world also had mental health problems. So, how did they deal with them?

As we’ll see, some of their insights about mental health are still relevant today, even though we might question some of their methods.

1. Our mental state is important

Mental health problems such as depression were familiar to people in the ancient world. Homer, the poet famous for the Iliad and Odyssey who lived around the eighth century BC, apparently died after wasting away from depression.

Already in the late fifth century BC, ancient Greek doctors recognised that our health partly depends on the state of our thoughts.

In the Epidemics, a medical text written in around 400BC, an anonymous doctor wrote that our habits about our thinking (as well as our lifestyle, clothing and housing, physical activity and sex) are the main determinants of our health.

2. Mental health problems can make us ill

Also writing in the Epidemics, an anonymous doctor described one of his patients, Parmeniscus, whose mental state became so bad he grew delirious, and eventually could not speak. He stayed in bed for 14 days before he was cured. We’re not told how.

Later, the famous doctor Galen of Pergamum (129-216AD) observed that people often become sick because of a bad mental state:

It may be that under certain circumstances ‘thinking’ is one of the causes that bring about health or disease because people who get angry about everything and become confused, distressed and frightened for the slightest reason often fall ill for this reason and have a hard time getting over these illnesses.

Galen also described some of his patients who suffered with their mental health, including some who became seriously ill and died. One man had lost money:

He developed a fever that stayed with him for a long time. In his sleep he scolded himself for his loss, regretted it and was agitated until he woke up. While he was awake he continued to waste away from grief. He then became delirious and developed brain fever. He finally fell into a delirium that was obvious from what he said, and he remained in this state until he died.

3. Mental illness can be prevented and treated

In the ancient world, people had many different ways to prevent or treat mental illness.

The philosopher Aristippus, who lived in the fifth century BC, used to advise people to focus on the present to avoid mental disturbance:

concentrate one’s mind on the day, and indeed on that part of the day in which one is acting or thinking. Only the present belongs to us, not the past nor what is anticipated. The former has ceased to exist, and it is uncertain if the latter will exist.

The philosopher Clinias, who lived in the fourth century BC, said that whenever he realised he was becoming angry, he would go and play music on his lyre to calm himself.

Doctors had their own approaches to dealing with mental health problems. Many recommended patients change their lifestyles to adjust their mental states. They advised people to take up a new regime of exercise, adopt a different diet, go travelling by sea, listen to the lectures of philosophers, play games (such as draughts/checkers), and do mental exercises equivalent to the modern crossword or sudoku.

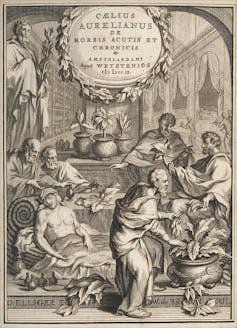

For instance, the physician Caelius Aurelianus (fifth century AD) thought patients suffering from insanity could benefit from a varied diet including fruit and mild wine.

Doctors also advised people to take plant-based medications. For example, the herb hellebore was given to people suffering from paranoia. However, ancient doctors recognised that hellebore could be dangerous as it sometimes induced toxic spasms, killing patients.

Other doctors, such as Galen, had a slightly different view. He believed mental problems were caused by some idea that had taken hold of the mind. He believed mental problems could be cured if this idea was removed from the mind and wrote:

a person whose illness is caused by thinking is only cured by taking care of the false idea that has taken over his mind, not by foods, drinks, [clothing, housing], baths, walking and other such (measures).

Galen thought it was best to deflect his patients’ thoughts away from these false ideas by putting new ideas and emotions in their minds:

I put fear of losing money, political intrigue, drinking poison or other such things in the hearts of others to deflect their thoughts to these things […] In others one should arouse indignation about an injustice, love of rivalry, and the desire to beat others depending on each person’s interest.

4. Addressing mental health needs effort

Generally speaking, the ancients believed keeping our mental state healthy required effort. If we were anxious or angry or despondent, then we needed to do something that brought us the opposite of those emotions.

This can be achieved, they thought, by doing some activity that directly countered the emotions we are experiencing.

For example, Caelius Aurelianus said people suffering from depression should do activities that caused them to laugh and be happy, such as going to see a comedy at the theatre.

However, the ancients did not believe any single activity was enough to make our mental state become healthy. The important thing was to make a wholesale change to one’s way of living and thinking.

When it comes to experiencing mental health problems, we clearly have a lot in common with our ancient ancestors. Much of what they said seems as relevant now as it did 2,000 years ago, even if we use different methods and medicines today.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Konstantine Panegyres, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, researching Greco-Roman antiquity, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It

We’ve talked before about how waist circumference is a much more useful indicator of metabolic health than BMI.

So, let’s say you’ve a bit more around the middle than you’d like, but it stubbornly stays there. What’s going on underneath what you can see, why is it going on, and how can you get it to change?

What is visceral fat?

First, let’s talk about subcutaneous fat. That’s the fat directly under your skin. Women usually have more than men, and that’s perfectly healthy (up to a point); it’s supposed to be that way. We (women) will tend to accumulate this mostly in places such as our breasts, hips, and butt, and work outwards from there. Men will tend to put it on more to the belly and face.

Side-note: if you’re undergoing (untreated) menopause, the changes in your hormone levels will tend to result in more subcutaneous fat to the belly and face too. That’s normal, and/but normal is not always good, and treatment options are great (with hormone replacement therapy, HRT, topping the list).

Visceral fat (also called visceral adipose tissue), on the other hand, is the fat of the viscera—the internal organs of the abdomen.

So, this is fat that goes under your abdominal muscles—you can’t squeeze this (directly).

So what can we do?

Famously “you can’t do spot reduction” (lose fat from a particular part of your body by focusing exercises on that area), but that’s about subcutaneous fat. There are things you can do that will reduce your visceral fat in particular.

Some of these advices you may think “that’s just good advice for losing fat in general” and it is, yes. But these are things that have the biggest impact on visceral fat.

Cut alcohol use

This is the biggie. By numerous mechanisms, some of which we’ve talked about before, alcohol causes weight gain in general yes, but especially for visceral fat.

Get better sleep

You might think that hitting the gym is most important, but this one ranks higher. Yes, you can trim visceral fat without leaving your bed (and even without getting athletic in bed, for that matter). Not convinced?

- Here’s a study of 101 people looking at sleep quality and abdominal adiposity

- Oh, and here’s a meta-analysis with 56,000 people (finding the same thing), in case that one study didn’t convince you.

So, the verdict is clear: you snooze, you lose (visceral fat)!

Tweak your diet

You don’t have to do a complete overhaul (unless you want to), but a few changes can make a big difference, especially:

- Getting more fiber (this is the biggie when it comes to diet)

- Eating less sugar (not really a surprise, but relevant to mention)

- Eat whole foods (skip the highly processed stuff)

If you’d like to learn more and enjoy videos, here’s an informative one to get you going!

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically! Share This Post

-

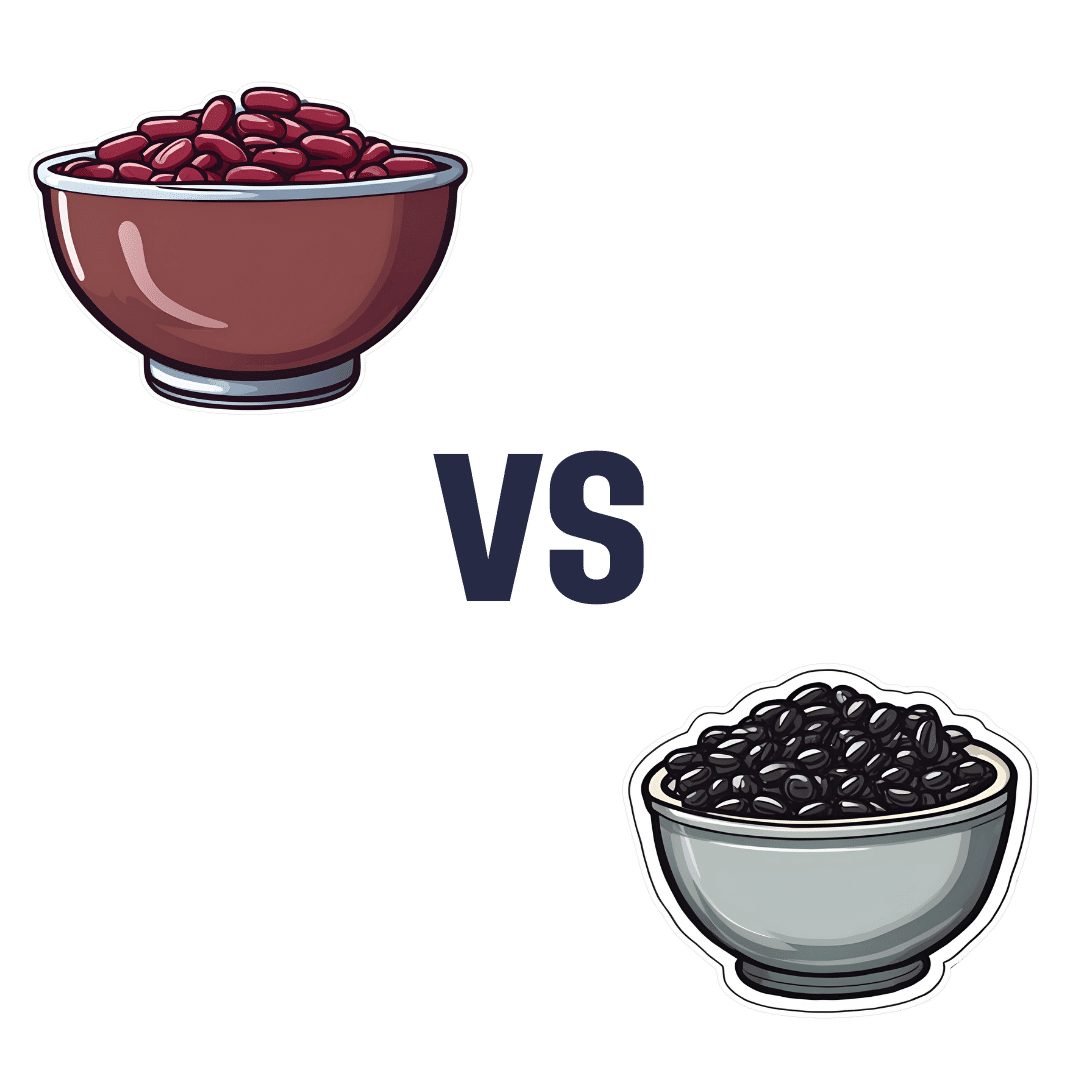

Kidney Beans or Black Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kidney beans to black beans, we picked the black beans.

Why?

First, do note that black beans are also known as turtle beans, or if one wants to hedge one’s bets, black turtle beans. It’s all the same bean. As a small linguistic note, kidney beans are known as “red beans” in many languages, so we could have called this “red beans vs black beans”, but that wouldn’t have landed so well with our largely anglophone readership. So, kidney beans vs black beans it is!

They’re certainly both great, and this is a close one today…

In terms of macros, they’re equal on protein and black beans have more carbs and/but also more fiber. So far, so equal—or rather, if one pulls ahead of the other here, it’s a matter of subjective priorities.

In the category of vitamins, they’re equal on vitamins B2, B3, and choline, while kidney beans have more of vitamins B6, B9, C, and K, and black beans have more of vitamins A, B1, B5, and E. In other words, the two beans are still tied with a 4:4 split, unless we want to take into account that that vitamin E difference is that black beans have 29x more vitamin E, in which case, black beans move ahead.

When it comes to minerals, finally the winner becomes apparent; while kidney beans have a little more manganese and zinc, on the other hand black beans have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium. However, it should be noted that honestly, the margins aren’t huge here and kidney beans are almost as good for all of these minerals.

In short, black beans win the day, but kidney beans are very close behind, so enjoy whichever you prefer, or better yet, both! They go great together in tacos, burritos, or similar, by the way.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Kidney Beans vs Fava Beans – Which is Healthier?

- Chickpeas vs Black Beans – Which is Healthier?

- Bold Beans – by Amelia Christie-Miller ← this is a recipe book; if you’re looking to incorporate more beans into your diet and want to make it good, this cookbook can lead the way!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Why Diets Make Us Fat – by Dr. Sandra Aamodt

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s well-known that crash-dieting doesn’t work. Restrictive diets will achieve short-term weight loss, but it’ll come back later. In the long term, weight creeps slowly upwards. Why?

Dr. Sandra Aamodt explores the science and sociology behind this phenomenon, and offers an evidence-based alternative.

A lot of the book is given over to explanations of what is typically going wrong—that is the title of the book, after all. From metabolic starvation responses to genetics to the negative feedback loop of poor body image, there’s a lot to address.

However, what alternative does she propose?

The book takes us on a shift away from focusing on the numbers on the scale, and more on building consistent healthy habits. It might not feel like it if you desperately want to lose weight, but it’s better to have healthy habits at any weight, than to have a wreck of physical and mental health for the sake of a lower body mass.

Dr. Aamodt lays out a plan for shifting perspectives, building health, and letting weight loss come by itself—as a side effect, not a goal.

In fact, as she argues (in agreement with the best current science, science that we’ve covered before at 10almonds, for that matter), that over a certain age, people in the “overweight” category of BMI have a reduced mortality risk compared to those in the “healthy weight” category. It really underlines how there’s no point in making oneself miserably unhealthy with the end goal of having a lighter coffin—and getting it sooner.

Bottom line: will this book make you hit those glossy-magazine weight goals by your next vacation? Quite possibly not, but it will set you up for actually healthier living, for life, at any weight.

Click here to check out Why Diets Make Us Fat, and live healthier and better!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Overdosing on Chemo: A Common Gene Test Could Save Hundreds of Lives Each Year

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One January morning in 2021, Carol Rosen took a standard treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Three gruesome weeks later, she died in excruciating pain from the very drug meant to prolong her life.

Rosen, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher, passed her final days in anguish, enduring severe diarrhea and nausea and terrible sores in her mouth that kept her from eating, drinking, and, eventually, speaking. Skin peeled off her body. Her kidneys and liver failed. “Your body burns from the inside out,” said Rosen’s daughter, Lindsay Murray, of Andover, Massachusetts.

Rosen was one of more than 275,000 cancer patients in the United States who are infused each year with fluorouracil, known as 5-FU, or, as in Rosen’s case, take a nearly identical drug in pill form called capecitabine. These common types of chemotherapy are no picnic for anyone, but for patients who are deficient in an enzyme that metabolizes the drugs, they can be torturous or deadly.

Those patients essentially overdose because the drugs stay in the body for hours rather than being quickly metabolized and excreted. The drugs kill an estimated 1 in 1,000 patients who take them — hundreds each year — and severely sicken or hospitalize 1 in 50. Doctors can test for the deficiency and get results within a week — and then either switch drugs or lower the dosage if patients have a genetic variant that carries risk.

Yet a recent survey found that only 3% of U.S. oncologists routinely order the tests before dosing patients with 5-FU or capecitabine. That’s because the most widely followed U.S. cancer treatment guidelines — issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network — don’t recommend preemptive testing.

The FDA added new warnings about the lethal risks of 5-FU to the drug’s label on March 21 following queries from KFF Health News about its policy. However, it did not require doctors to administer the test before prescribing the chemotherapy.

The agency, whose plan to expand its oversight of laboratory testing was the subject of a House hearing, also March 21, has said it could not endorse the 5-FU toxicity tests because it’s never reviewed them.

But the FDA at present does not review most diagnostic tests, said Daniel Hertz, an associate professor at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy. For years, with other doctors and pharmacists, he has petitioned the FDA to put a black box warning on the drug’s label urging prescribers to test for the deficiency.

“FDA has responsibility to assure that drugs are used safely and effectively,” he said. The failure to warn, he said, “is an abdication of their responsibility.”

The update is “a small step in the right direction, but not the sea change we need,” he said.

Europe Ahead on Safety

British and European Union drug authorities have recommended the testing since 2020. A small but growing number of U.S. hospital systems, professional groups, and health advocates, including the American Cancer Society, also endorse routine testing. Most U.S. insurers, private and public, will cover the tests, which Medicare reimburses for $175, although tests may cost more depending on how many variants they screen for.

In its latest guidelines on colon cancer, the Cancer Network panel noted that not everyone with a risky gene variant gets sick from the drug, and that lower dosing for patients carrying such a variant could rob them of a cure or remission. Many doctors on the panel, including the University of Colorado oncologist Wells Messersmith, have said they have never witnessed a 5-FU death.

In European hospitals, the practice is to start patients with a half- or quarter-dose of 5-FU if tests show a patient is a poor metabolizer, then raise the dose if the patient responds well to the drug. Advocates for the approach say American oncology leaders are dragging their feet unnecessarily, and harming people in the process.

“I think it’s the intransigence of people sitting on these panels, the mindset of ‘We are oncologists, drugs are our tools, we don’t want to go looking for reasons not to use our tools,’” said Gabriel Brooks, an oncologist and researcher at the Dartmouth Cancer Center.

Oncologists are accustomed to chemotherapy’s toxicity and tend to have a “no pain, no gain” attitude, he said. 5-FU has been in use since the 1950s.

Yet “anybody who’s had a patient die like this will want to test everyone,” said Robert Diasio of the Mayo Clinic, who helped carry out major studies of the genetic deficiency in 1988.

Oncologists often deploy genetic tests to match tumors in cancer patients with the expensive drugs used to shrink them. But the same can’t always be said for gene tests aimed at improving safety, said Mark Fleury, policy director at the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network.

When a test can show whether a new drug is appropriate, “there are a lot more forces aligned to ensure that testing is done,” he said. “The same stakeholders and forces are not involved” with a generic like 5-FU, first approved in 1962, and costing roughly $17 for a month’s treatment.

Oncology is not the only area in medicine in which scientific advances, many of them taxpayer-funded, lag in implementation. For instance, few cardiologists test patients before they go on Plavix, a brand name for the anti-blood-clotting agent clopidogrel, although it doesn’t prevent blood clots as it’s supposed to in a quarter of the 4 million Americans prescribed it each year. In 2021, the state of Hawaii won an $834 million judgment from drugmakers it accused of falsely advertising the drug as safe and effective for Native Hawaiians, more than half of whom lack the main enzyme to process clopidogrel.

The fluoropyrimidine enzyme deficiency numbers are smaller — and people with the deficiency aren’t at severe risk if they use topical cream forms of the drug for skin cancers. Yet even a single miserable, medically caused death was meaningful to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where Carol Rosen was among more than 1,000 patients treated with fluoropyrimidine in 2021.

Her daughter was grief-stricken and furious after Rosen’s death. “I wanted to sue the hospital. I wanted to sue the oncologist,” Murray said. “But I realized that wasn’t what my mom would want.”

Instead, she wrote Dana-Farber’s chief quality officer, Joe Jacobson, urging routine testing. He responded the same day, and the hospital quickly adopted a testing system that now covers more than 90% of prospective fluoropyrimidine patients. About 50 patients with risky variants were detected in the first 10 months, Jacobson said.

Dana-Farber uses a Mayo Clinic test that searches for eight potentially dangerous variants of the relevant gene. Veterans Affairs hospitals use a 11-variant test, while most others check for only four variants.

Different Tests May Be Needed for Different Ancestries

The more variants a test screens for, the better the chance of finding rarer gene forms in ethnically diverse populations. For example, different variants are responsible for the worst deficiencies in people of African and European ancestry, respectively. There are tests that scan for hundreds of variants that might slow metabolism of the drug, but they take longer and cost more.

These are bitter facts for Scott Kapoor, a Toronto-area emergency room physician whose brother, Anil Kapoor, died in February 2023 of 5-FU poisoning.

Anil Kapoor was a well-known urologist and surgeon, an outgoing speaker, researcher, clinician, and irreverent friend whose funeral drew hundreds. His death at age 58, only weeks after he was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer, stunned and infuriated his family.

In Ontario, where Kapoor was treated, the health system had just begun testing for four gene variants discovered in studies of mostly European populations. Anil Kapoor and his siblings, the Canadian-born children of Indian immigrants, carry a gene form that’s apparently associated with South Asian ancestry.

Scott Kapoor supports broader testing for the defect — only about half of Toronto’s inhabitants are of European descent — and argues that an antidote to fluoropyrimidine poisoning, approved by the FDA in 2015, should be on hand. However, it works only for a few days after ingestion of the drug and definitive symptoms often take longer to emerge.

Most importantly, he said, patients must be aware of the risk. “You tell them, ‘I am going to give you a drug with a 1 in 1,000 chance of killing you. You can take this test. Most patients would be, ‘I want to get that test and I’ll pay for it,’ or they’d just say, ‘Cut the dose in half.’”

Alan Venook, the University of California-San Francisco oncologist who co-chairs the panel that sets guidelines for colorectal cancers at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, has led resistance to mandatory testing because the answers provided by the test, in his view, are often murky and could lead to undertreatment.

“If one patient is not cured, then you giveth and you taketh away,” he said. “Maybe you took it away by not giving adequate treatment.”

Instead of testing and potentially cutting a first dose of curative therapy, “I err on the latter, acknowledging they will get sick,” he said. About 25 years ago, one of his patients died of 5-FU toxicity and “I regret that dearly,” he said. “But unhelpful information may lead us in the wrong direction.”

In September, seven months after his brother’s death, Kapoor was boarding a cruise ship on the Tyrrhenian Sea near Rome when he happened to meet a woman whose husband, Atlanta municipal judge Gary Markwell, had died the year before after taking a single 5-FU dose at age 77.

“I was like … that’s exactly what happened to my brother.”

Murray senses momentum toward mandatory testing. In 2022, the Oregon Health & Science University paid $1 million to settle a suit after an overdose death.

“What’s going to break that barrier is the lawsuits, and the big institutions like Dana-Farber who are implementing programs and seeing them succeed,” she said. “I think providers are going to feel kind of bullied into a corner. They’re going to continue to hear from families and they are going to have to do something about it.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Ideal Blood Pressure Numbers Explained

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Maybe I missed it but the study on blood pressure did it say what the 2 numbers should read ideally?❞

We linked it at the top of the article rather than including it inline, as we were short on space (and there was a chart rather than a “these two numbers” quick answer), but we have a little more space today, so:

Category Systolic (mm Hg) Diastolic (mm Hg) Normal < 120 AND < 80 Elevated 120 – 129 AND < 80 Stage 1 – High Blood Pressure 130 – 139 OR 80 – 89 Stage 2 – High Blood Pressure 140 or higher OR 90 or higher Hypertensive Crisis Above 180 AND/OR Above 120 To oversimplify for a “these two numbers” answer, under 120/80 is generally considered good, unless it is under 90/60, in which case that becomes hypotension.

Hypotension, the blood pressure being too low, means your organs may not get enough oxygen and if they don’t, they will start shutting down.

To give you an idea how serious this, this is the closed-circuit equivalent of the hypovolemic shock that occurs when someone is bleeding out onto the floor. Technically, bleeding to death also results in low blood pressure, of course, hence the similarity.

So: just a little under 120/80 is great.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Here’s how to help protect babies and kids from RSV

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- RSV is a respiratory virus that is especially dangerous for babies and young children.

- There are two ways to help protect babies from RSV: vaccination during pregnancy and giving babies nirsevimab, an RSV antibody shot.

- If someone in your household has RSV, watch for signs of severe illness and take steps to help prevent it from spreading.

Respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, is a very contagious seasonal respiratory illness that is especially dangerous for infants and young children. Cases rose dramatically last month, and an increasing number of kids and older adults with RSV are being hospitalized across the United States.

Fortunately, pregnant people can get vaccinated during pregnancy or get their infants and young children an RSV antibody shot to help them stay healthy.

Read on to learn about symptoms of RSV, how to help prevent infants and children from getting very sick, and what families should do if someone in their household is sick with the virus.

What are the symptoms of RSV in babies and young children?

RSV symptoms in young children may include a runny nose, decreased eating and drinking, and coughing, which may lead to wheezing and difficulty breathing.

Infants with RSV may show symptoms like irritability, decreased activity and appetite, and life-threatening pauses in breathing (apnea) that last for more than 10 seconds. Most infants with RSV will not develop a fever, but babies who are born prematurely, have weakened immune systems, or have chronic lung disease are more likely to become very sick.

Who is eligible for an RSV antibody shot?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that babies younger than 8 months whose gestational parent did not receive an RSV vaccine during pregnancy receive nirsevimab between October and March, when RSV typically peaks. This antibody shot delivers proteins that can help protect them against RSV.

Nirsevimab is also recommended for children between 8 and 19 months who are at increased risk of severe RSV, including children who are born prematurely, have chronic lung disease or severe cystic fibrosis, are immunocompromised, or are American Indians or Alaska Natives.

Nirsevimab is typically covered by insurance or costs $495 out of pocket. Children who are eligible for the CDC’s Vaccines for Children Program can receive nirsevimab at no cost.

How can families help prevent RSV from spreading?

It’s recommended that children and adults who are sick with RSV stay home and away from others. If your infant or child has difficulty breathing or develops blue or gray skin, take them to an emergency room right away.

People who are infected with RSV can spread the disease when they cough or sneeze; have close contact with others; or touch, cough, or sneeze on shared surfaces. Help protect your family from catching and spreading RSV at home and in public places by ensuring that everyone covers their mouths during coughing and sneezing, washes their hands often, and wears a high-quality, well-fitting mask.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: