White Noise vs Pink Noise

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I live in a large city and even late at night there is always a bit of background noise. While I am pretty used to it by now, I find I don’t sleep nearly as well in the city as I do in the country. I have seen some stuff about “white noise” generators. I was wondering whether you have any thoughts about the science behind these, and whether it is something I should try out – or maybe I should be trying something completly different.❞

The science says…

❝Our data show that white noise significantly improved sleep based on subjective and objective measurements in subjects complaining of difficulty sleeping due to high levels of environmental noise. This suggests that the application of white noise may be an effective tool in helping to improve sleep in those settings.❞

That said, you might also consider “pink noise”, which is very similar to white noise (having all frequencies normally audible to the human ear), but has greater intensity of lower frequencies, creating a more deep and even sound. While white noise and pink noise are both great at “muting” external sounds like those that have been disturbing your sleep, pink noise may have an advantage in helping to stimulate deep and restful sleep:

❝This study demonstrates that steady pink noise has significant effect on reducing brain wave complexity and inducing more stable sleep time to improve sleep quality of individuals.❞

Source: Pink noise: effect on complexity synchronization of brain activity and sleep consolidation

There may be extra benefits to pink noise, too:

Acoustic Enhancement of Sleep Slow Oscillations and Concomitant Memory Improvement in Older Adults

Rest well!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What’s the difference between Alzheimer’s and dementia?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

Changes in thinking and memory as we age can occur for a variety of reasons. These changes are not always cause for concern. But when they begin to disrupt daily life, it could indicate the first signs of dementia.

Another term that can crop up when we’re talking about dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, or Alzheimer’s for short.

So what’s the difference?

Lightspring/Shutterstock What is dementia?

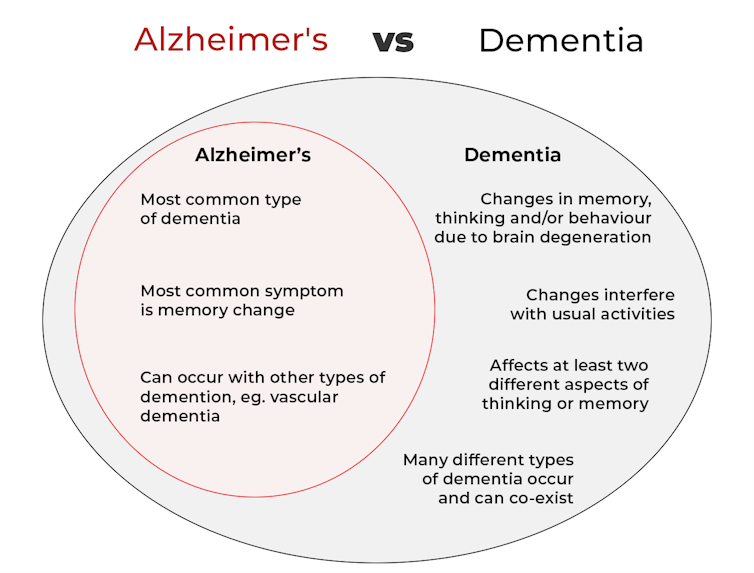

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of syndromes that result in changes in memory, thinking and/or behaviour due to degeneration in the brain.

To meet the criteria for dementia these changes must be sufficiently pronounced to interfere with usual activities and are present in at least two different aspects of thinking or memory.

For example, someone might have trouble remembering to pay bills and become lost in previously familiar areas.

It’s less-well known that dementia can also occur in children. This is due to progressive brain damage associated with more than 100 rare genetic disorders. This can result in similar cognitive changes as we see in adults.

So what’s Alzheimer’s then?

Alzheimer’s is the most common type of dementia, accounting for about 60-80% of cases.

So it’s not surprising many people use the terms dementia and Alzheimer’s interchangeably.

Changes in memory are the most common sign of Alzheimer’s and it’s what the public most often associates with it. For instance, someone with Alzheimer’s may have trouble recalling recent events or keeping track of what day or month it is.

People with dementia may have trouble keeping track of dates. Daisy Daisy/Shutterstock We still don’t know exactly what causes Alzheimer’s. However, we do know it is associated with a build-up in the brain of two types of protein called amyloid-β and tau.

While we all have some amyloid-β, when too much builds up in the brain it clumps together, forming plaques in the spaces between cells. These plaques cause damage (inflammation) to surrounding brain cells and leads to disruption in tau. Tau forms part of the structure of brain cells but in Alzheimer’s tau proteins become “tangled”. This is toxic to the cells, causing them to die. A feedback loop is then thought to occur, triggering production of more amyloid-β and more abnormal tau, perpetuating damage to brain cells.

Alzheimer’s can also occur with other forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia. This combination is the most common example of a mixed dementia.

Vascular dementia

The second most common type of dementia is vascular dementia. This results from disrupted blood flow to the brain.

Because the changes in blood flow can occur throughout the brain, signs of vascular dementia can be more varied than the memory changes typically seen in Alzheimer’s.

For example, vascular dementia may present as general confusion, slowed thinking, or difficulty organising thoughts and actions.

Your risk of vascular dementia is greater if you have heart disease or high blood pressure.

Frontotemporal dementia

Some people may not realise that dementia can also affect behaviour and/or language. We see this in different forms of frontotemporal dementia.

The behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia is the second most common form (after Alzheimer’s disease) of younger onset dementia (dementia in people under 65).

People living with this may have difficulties in interpreting and appropriately responding to social situations. For example, they may make uncharacteristically rude or offensive comments or invade people’s personal space.

Semantic dementia is also a type of frontotemporal dementia and results in difficulty with understanding the meaning of words and naming everyday objects.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies results from dysregulation of a different type of protein known as α-synuclein. We often see this in people with Parkinson’s disease.

So people with this type of dementia may have altered movement, such as a stooped posture, shuffling walk, and changes in handwriting. Other symptoms include changes in alertness, visual hallucinations and significant disruption to sleep.

Do I have dementia and if so, which type?

If you or someone close to you is concerned, the first thing to do is to speak to your GP. They will likely ask you some questions about your medical history and what changes you have noticed.

Sometimes it might not be clear if you have dementia when you first speak to your doctor. They may suggest you watch for changes or they may refer you to a specialist for further tests.

There is no single test to clearly show if you have dementia, or the type of dementia. A diagnosis comes after multiple tests, including brain scans, tests of memory and thinking, and consideration of how these changes impact your daily life.

Not knowing what is happening can be a challenging time so it is important to speak to someone about how you are feeling or to reach out to support services.

Dementia is diverse

As well as the different forms of dementia, everyone experiences dementia in different ways. For example, the speed dementia progresses varies a lot from person to person. Some people will continue to live well with dementia for some time while others may decline more quickly.

There is still significant stigma surrounding dementia. So by learning more about the various types of dementia and understanding differences in how dementia progresses we can all do our part to create a more dementia-friendly community.

The National Dementia Helpline (1800 100 500) provides information and support for people living with dementia and their carers. To learn more about dementia, you can take this free online course.

Nikki-Anne Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

The Web That Has No Weaver – by Ted Kaptchuk

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

At 10almonds we have a strong “stick with the science” policy, and that means peer-reviewed studies and (where such exists) scientific consensus.

However, in the spirit of open-minded skepticism (i.e., acknowledging what we don’t necessarily know), it can be worth looking at alternatives to popular Western medicine. Indeed, many things have made their way from Traditional Chinese Medicine (or Ayurveda, or other systems) into Western medicine in any case.

“The Web That Has No Weaver” sounds like quite a mystical title, but the content is presented in the cold light of day, with constant “in Western terms, this works by…” notes.

The author walks a fine line of on the one hand, looking at where TCM and Western medicine may start and end up at the same place, by a different route; and on the other hand, noting that (in a very Daoist fashion), the route is where TCM places more of the focus, in contrast to Western medicine’s focus on the start and end.

He makes the case for TCM being more holistic, and it is, though Western medicine has been catching up in this regard since this book’s publication more than 20 years ago.

The style of the writing is very easy to follow, and is not esoteric in either mysticism or scientific jargon. There are diagrams and other illustrations, for ease of comprehension, and chapter endnotes make sure we didn’t miss important things.

Bottom line: if you’re curious about Traditional Chinese Medicine, this book is the US’s most popular introduction to such, and as such, is quite a seminal text.

Click here to check out The Web That Has No Weaver, and enjoy learning about something new!

Share This Post

-

Shame and blame can create barriers to vaccination

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Understanding the stigma surrounding infectious diseases like HIV and mpox may help community health workers break down barriers that hinder access to care.

Looking back in history can provide valuable lessons to confront stigma in health care today, especially toward Black, Latine, LGBTQ+, and other historically underserved communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and HIV.

Public Good News spoke with Sam Brown, HIV prevention and wellness program manager at Civic Heart, a community-based organization in Houston’s historic Third Ward, to understand the effects of stigma around sexual health and vaccine uptake.

Brown shared more about Civic Heart’s efforts to provide free confidential testing for sexually transmitted infections, counseling and referrals, and information about COVID-19, flu, and mpox vaccinations, as well as the lessons they’re learning as they strive for vaccine equity.

Here’s what Brown said.

[Editor’s note: This content has been edited for clarity and length.]

PGN: Some people on social media have spread the myth that vaccines cause AIDS or other immune deficiencies when the opposite is true: Vaccines strengthen our immune systems to help protect against disease. Despite being frequently debunked, how do false claims like these impact the communities you serve?

Sam Brown: Misinformation like that is so hard to combat. And it makes the work and the path to overall community health hard because people will believe it. In the work that we do, 80 percent of it is changing people’s perspective on something they thought they knew.

You know, people don’t even transmit AIDS. People transmit HIV. So, a vaccine causing immunodeficiency doesn’t make sense.

With the communities we serve, we might have a person that will believe the myth, and because they believe it, they won’t get vaccinated. Then later, they may test positive for COVID-19.

And depending on social determinants of health, it can impact them in a whole heap of ways: That person is now missing work, they’re not able to provide for their family—if they have a family. It’s this mindset that can impact a person’s life, their income, their ability to function.

So, to not take advantage of something like a vaccine that’s affordable, or free for the most part, just because of misinformation or a misunderstanding—that’s detrimental, you know.

For example, when we talk to people in the community, many don’t know that they can get mpox from their pet, or that it’s zoonotic—that means that it can be transferred between different species or different beings, from animals to people. I see a lot of surprise and shock [when people learn this].

It’s difficult because we have to fight the misinformation and the stigma that comes with it. And it can be a big barrier.

People misunderstand. [They] think that “this is something that gay people or the LGBTQ+ community get,” which is stigmatizing and comes off as blaming. And blaming is the thing that leads us to be misinformed.

PGN: In the last couple years, your organization’s HIV Wellness program has taken on promoting COVID-19, flu, and mpox vaccines to the communities you serve. How do you navigate conversations between sexual health and infectious diseases? Can you share more about your messaging strategies?

S.B.: As we promoted positive sexual health and HIV prevention, we saw people were tired of hearing about HIV. They were tired of hearing about how PrEP works, or how to prevent HIV.

But, when we had an outbreak of syphilis in Houston just last year, people were more inclined to test because of the severity of the outbreak.

So, what our team learned is that sometimes you have to change the message to get people what they need.

We changed our message to highlight more syphilis information and saw that we were able to get more people tested for HIV because we correlated how syphilis and HIV are connected and how a person can be susceptible to both.

Using messages that the community wants and pairing them with what the community needs has been better for us. And we see that same thing with COVID-19, the flu, and RSV. Sometimes you just can’t be married to a message. We’ve had to be flexible to meet our clients where they are to help them move from unsafe practices to practices that are healthy and good for them and their communities.

PGN: You’ve mentioned how hard it is to combat stigma in your work. How do you effectively address it when talking to people one-on-one?

S.B.: What I understand is that no one wants to feel shame. What I see people respond to is, “Here’s an opportunity to do something different. Maybe there was information that you didn’t know that caused you to make a bad decision. And now here’s an opportunity to gain information so that you can make a better decision.”

People want to do what they want to do; they want to live how they want to live. And we all should be able to do that as long as it’s not hurting anyone, but also being responsible enough to understand that, you know, COVID-19 is here.

So, instead of shaming and blaming, it’s best to make yourself aware and understand what it is and how to treat it. Because the real enemy is the virus—it’s the infection, not the people.

When we do our work, we want to make sure that we come from a strengths-based approach. We always look at what a client can do, what that client has. We want to make sure that we’re empowering them from that point. So, even if they choose not to prioritize our message right now, we can’t take that personally. We’ll just use it as a chance to try a new way of framing it to help people understand what we’re trying to say.

And sometimes that can be difficult, even for organizations. But getting past that difficulty comes with a greater opportunity to impact someone else.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How To Improve Your Heart Rate Variability

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How’s your heart rate variability?

The hallmarks of a good, strong cardiovascular system include a medium-to-low resting heart rate (for adults: under 60 beats per minute is good; under 50 is typical of athletes), and healthy blood pressure (for adults: under 120/80, while still above 90/60, is generally considered good).

Less talked-about is heart rate variability, but it’s important too…

What is heart rate variability?

Heart rate variability is a measure of how quickly and easily your heart responds to changes in demands placed upon it. For example:

- If you’re at rest and then start running your fastest (be it for leisure or survival or anything in between), your heart rate should be able to jump from its resting rate to about 180% of that as quickly as possible

- When you stop, your heart rate should be able to shift gears back to your resting rate as quickly as possible

The same goes, to a commensurately lesser extent, to changes in activity between low and moderate, or between moderate and high.

- When your heart can change gears quickly, that’s called a high heart rate variability

- When your heart is sluggish to get going and then takes a while to return to normal after exertion, that’s called a low heart rate variability.

The rate of change (i.e., the variability) is measured in microseconds per beat, and the actual numbers will vary depending on a lot of factors, but for everyone, higher is better than lower.

Aside from quick response to crises, why does it matter?

If heart rate variability is low, it means the sympathetic nervous system is dominating the parasympathetic nervous system, which means, in lay terms, your fight-or-flight response is overriding your ability to relax.

See for example: Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature

This has a lot of knock-on effects for both physical and mental health! Your heart and brain will take the worst of this damage, so it’s good to improve things for them impossible.

This Saturday’s Life Hacks: how to improve your HRV!

Firstly, the Usual Five Things™:

- A good diet (that avoids processed foods)

- Good exercise (that includes daily physical activity—more often is more important than more intense!)

- Good sleep (7–9 hours of good quality sleep per night)

- Reduce or eliminate alcohol consumption (this is dose-dependent; any reduction is an improvement)

- Don’t smoke (just don’t)

Additional regular habits that help a lot:

- Breathing exercises, mindfulness, meditation

- Therapy, especially CBT and DBT

- Stress-avoidance strategies, for example:

- Get (and maintain) your finances in good order

- Get (and maintain) your relationship(s) in good order

- Get (and maintain) your working* life in good order

*Whatever this means to you. If you’re perhaps retired, or otherwise a home-maker, or even a student, the things you “need to do” on a daily basis are your working life, for these purposes.

In terms of simple, quick-fix, physical tweaks to focus on if you’re already broadly leading a good life, two great ones are:

- Exercise: get moving! Walk to the store even if you buy nothing but a snack or drink to enjoy while walking back. If you drove, make more trips with the shopping bags rather than fewer. If you like to watch TV, consider an exercise bike or treadmill to use while watching. If you have a partner, double-up and make it a thing you do together! Take the stairs instead of the elevator. Take the scenic route when walking someplace. Go to the bathroom that’s further away. Every little helps!

- Breathe: even just a couple of times a day, practice mindful breathing. Start with even just a minute a day, to get the habit going. What breathing exercise you do isn’t so important as that you do it. Notice your breathing; count how long each breath takes. Don’t worry about “doing it right”—you’re doing great, just observe, just notice, just slowly count. We promise that regular practice of this will have you feeling amazing

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Many Health Benefits of Garlic

We’re quite confident you already know what garlic is, so we’re going to leap straight in there with some science today:

First, let’s talk about allicin

Allicin is a compound in garlic that gives most of its health benefits. A downside of allicin is that it’s not very stable, so what this means is:

- Garlic is best fresh—allicin breaks down soon after garlic is cut/crushed

- So while doing the paperwork isn’t fun, buying it as bulbs is better than buying it as granules or similar

- Allicin also breaks down somewhat in cooking, so raw garlic is best

- Our philosophy is: still use it in cooking as well; just use more!

- Supplements (capsule form etc) use typically use extracts and potency varies (from not great to actually very good)

Read more about that:

- Short-term heating reduces the anti-inflammatory effects of fresh raw garlic extracts

- Allicin Bioavailability and Bioequivalence from Garlic Supplements and Garlic Foods

Now, let’s talk benefits…

Benefits to heart health

Garlic has been found to be as effective as the drug Atenolol at reducing blood pressure:

It also lowers LDL (bad cholesterol):

Benefits to the gut

We weren’t even looking for this, but as it turns out, as an add-on to the heart benefits…

Benefits to the immune system

Whether against the common cold or bringing out the heavy guns, garlic is a booster:

- Preventing the common cold with a garlic supplement: a double-blind, placebo-controlled survey

- Supplementation with aged garlic extract improves both NK and γδ-T cell function and reduces the severity of cold and flu symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled nutrition intervention

Benefits to the youthfulness of body and brain

Garlic is high in antioxidants that, by virtue of reducing oxidative stress, help slow aging. This effect, combined with the cholesterol and blood pressure benefits, means it may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia:

- Antioxidant health effects of aged garlic extract

- Effects of garlic consumption on plasma and erythrocyte antioxidant parameters in elderly subjects

- Garlic reduces heart disease and dementia risk

There are more benefits too…

That’s all we have time to dive into study-wise today, but for the visually-inclined, here are yet more benefits to garlic (at a rate of 3–4 cloves per day):

An incredible awesome recipe using lots of garlic:

- Take small potatoes (still in their skins), cut in half

- Add enough peeled cloves of garlic so that you have perhaps a 1:10 ratio of garlic to potato by mass

- Boil (pressure-cooking is ideal) until soft, and drain

- Keeping them in the pan, add a lashing of olive oil, and any additional seasonings per your preference (consider black pepper, rosemary, thyme, parsley)

- Put a lid on the pan, and holding it closed, shake the pan vigorously

- Note: if you didn’t leave the skins on, or you chopped much larger potatoes smaller instead of cutting in half, the potatoes will break up into a rough mash now. This is actually also fine and still tastes (and honestly, looks) great, but it is different, so just be aware, so that you get the outcome you want.

- The garlic, which—unlike the potatoes—didn’t have a skin to hold it together, will now have melted over the potatoes like butter

You can serve like this (it’s delicious already) or finish up in the oven or air-fryer or under the grill, if you prefer a roasted style dish (an amazing option too).

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

- Garlic is best fresh—allicin breaks down soon after garlic is cut/crushed

-

How To Lower Your Blood Pressure (Cardiologists Explain)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Today we enjoy the benefit of input from Dr. Zalzal, Dr. Weeing, and Dr. Hefferman!

If the thought of being in an operating room with three cardiologists in scrubs doesn’t raise your blood pressure too much, the doctors in question have a lot to offer for bringing those numbers down and keeping them down! They recommend…

150 mins of Exercise

This isn’t exactly controversial, but: move your body!

See also: Exercise Less; Move More

Reduce salt

Most people eating the Standard American Diet (SAD) are getting far too much—mostly because it’s in so many processed foods already.

See also: How Too Much Salt May Lead To Organ Failure

Eating habits

There’s a lot more to eating healthily for the heart than just reducing salt, and over all, the Mediterranean diet comes out scoring highest:

- What Is The Mediterranean Diet Anyway? ← a primer for the uncertain

- Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean ← includes a heart-specialized version!

Reduce alcohol

According to the WHO, the only healthy amount of alcohol is zero. According to these cardiologists: at the very least cut down. However much or little you’re drinking right now, less is better.

See also: How To Reduce Or Quit Alcohol

Maintain healthy weight

While the doctors agree that BMI isn’t a great method of measuring metabolic health, it is clear that carrying excessive weight isn’t good for the heart.

See also: Lose Weight (Healthily!)

No smoking

This one’s pretty straight forward: just don’t.

See also: Addiction Myths That Are Hard To Quit

Reduce stress

Chronic stress has a big impact on chronic health in general and that includes its effect on blood pressure. So, improving one improves the other.

See also: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

Good sleep

Quality matters as much as quantity, and that goes for its effect on your blood pressure too, so take the time to invest in your good health!

See also: The 6 Dimensions Of Sleep (And Why They Matter)

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: