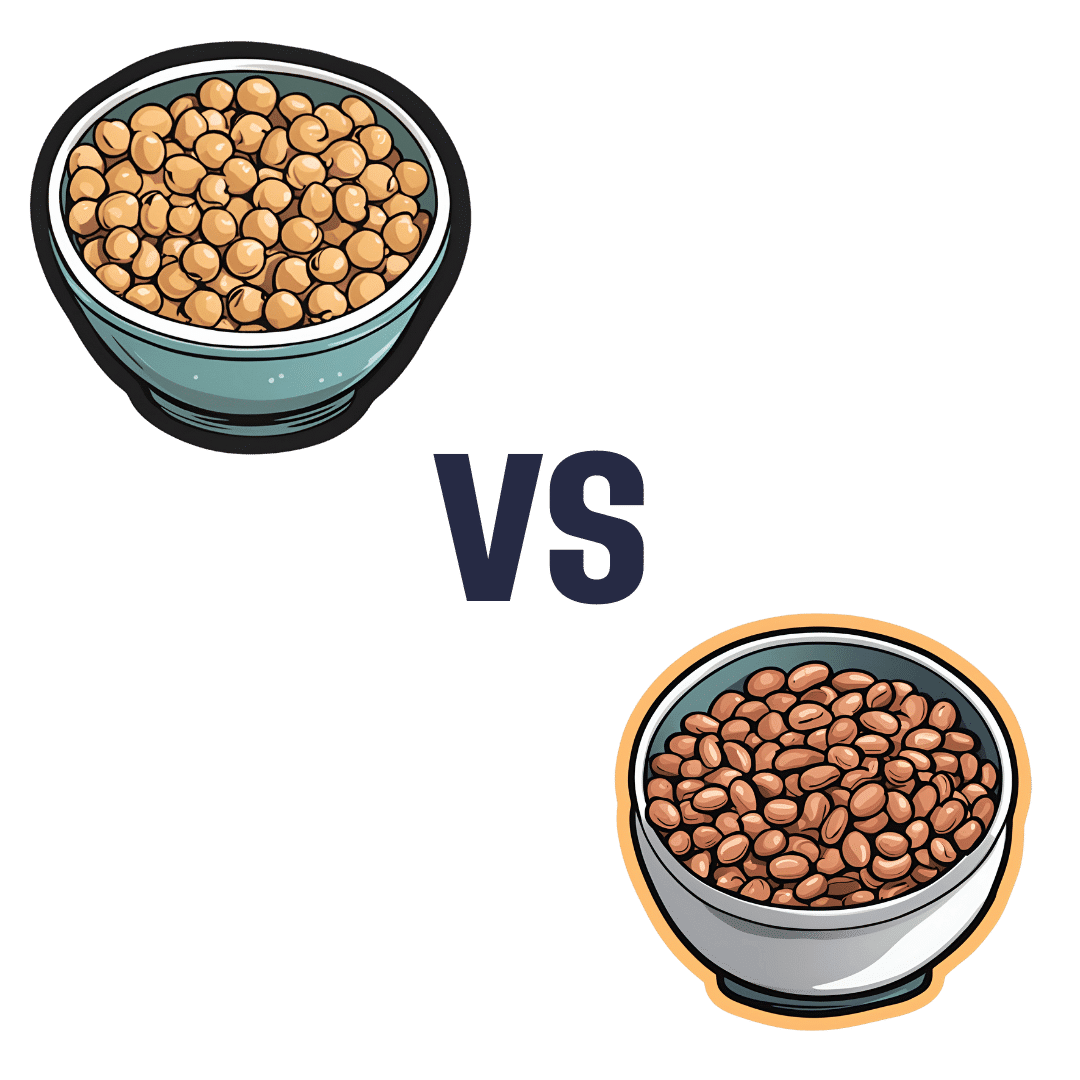

Chickpeas vs Pinto Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing chickpeas to pinto beans, we picked the pinto beans.

Why?

Both are great! And an argument could be made for either…

In terms of macros, pinto beans have slightly more fiber and slightly more protein, while chickpeas have slightly more carbs, and thus predictably higher net carbs. In the category of those proteins, they both have a comparable spread of amino acods, with pinto beans having very slightly more of each amino acid. All this adds up to a clear, but moderate, win for pinto beans.

When it comes to vitamins, technically chickpeas have more of vitamins A, B3, B5, C, K, and choline, but the margins are so small as to be almost meaningless. Meanwhile, pinto beans have more of vitamins B1, B6, and E, and/but the only one where the margin is enough to really care about is vitamin E (a little over 2x what chickpeas have). So, an argument could be made either way, but we’re going to call this category a tie.

The story with minerals is similar; chickpeas have more copper, iron, manganese, phosphorus, and zinc, all with small margins, while pinto beans have more potassium and selenium, and/but also less sodium. We’d call this either a tie, or a very slight win for chickpeas.

Adding up the sections gives for a very modest win for pinto beans, but as we say, an argument could be made for either.

Certainly, enjoy both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Chickpeas vs Black Beans – Which is Healthier?

- Kidney Beans vs Fava Beans – Which is Healthier?

- What Matters Most For Your Heart? Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Health Shots − by Toby Amidor

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First a quick note on qualifications: while not a doctor, she’s a RD, CDN, FAND, and as such, this is a very nutrition-focused book.

As a general rule of thumb, juices are unhealthy because of being largely liquid sugar and no fiber, but in this case:

- even the juice-based tonics are very small portions, so even if some have a high glycemic index, they’ll still have a low glycemic load, which means that having one is unlikely to spike blood glucose and thus insulin

- many of the tonics have fiber in any case, due to how they are made.

The tonics are divided into sections per what one wants to focus on, e.g. anti-inflammatory, brain health, sleep, gut health, skin/nails/hair, etc.

That said, some of the recipes are a little optimistic about how much effect the dosage present will have. For example, we calculate an an average of 0.03mg of resveratrol in her grape-based shot boasting resveratrol benefits. For contrast, resveratrol supplements range from 500mg to 200mg. So, to get the equivalent of the least generous supplement, you’d need to drink 16,667 shots.

Bottom line: some of the the health claims in this book are overstated, but by and large, it’s hard to go wrong consuming more plants, and these “health shots” are not a bad way to get a good dose of phytonutrients without hitting glycemic problems.

Share This Post

-

Whole – by Dr. T. Colin Campbell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most of us have at least a broad idea of what we’re supposed to be eating, what nutrients we should be getting. Many of us look at labels, and try to get our daily dose of this and that and the other.

And what we don’t get from food? There are supplements.

Dr. Campbell thinks we can do better:

Perhaps most critical in this book, where it stands out from others (we may already know, for example, that we should try to eat diverse plants and whole foods) is its treatment of why many supplements aren’t helpful.

We tend to hear “supplements are a waste of money” and sometimes they are, sometimes they aren’t. How to know the difference?

Key: things directly made from whole food sources will tend to be better. Seems reasonable, but… why? The answer lies in what else those foods contain. An apple may contain a small amount of vitamin C, less than a vitamin C tablet, but also contains a whole host of other things—tiny phytonutrients, whose machinations are mostly still mysteries to us—that go with that vitamin C and help it work much better. Lab-made supplements won’t have those.

There’s a lot more to the book… A chunk of which is a damning critique of the US healthcare system (the author argues it would be better named a sicknesscare system). We also learn about getting a good balance of macro- and micronutrients from our diet rather than having to supplement so much.

The style is conversational, while not skimping on the science. The author has had more than 150 papers published in peer-reviewed journals, and is no stranger to the relevant academia. Here, however, he focuses on making things easily comprehensible to the lay reader.

In short: if you’ve ever wondered how you’re doing at getting a good nutritional profile, and how you could do better, this is definitely the book for you.

Click here to check out “Whole” on Amazon today, and level up your daily diet!

Share This Post

-

How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Overcoming Loneliness & Isolation

One of the biggest mental health threats that faces many of us as we get older is growing isolation, and the loneliness that can come with it. Family and friends thin out over the years, and getting out and about isn’t always as easy as it used to be for everyone.

Nor is youth a guaranteed protection against this—in today’s world of urban sprawl and nothing-is-walkable cities, in which access to social spaces such as cafés and the like means paying the rising costs with money that young people often don’t have… And that’s without getting started on how much the pandemic impacted an entire generation’s social environments (or lack thereof).

Why is this a problem?

Humans are, by evolution, social creatures. As individuals we may have something of a spectrum from introvert to extrovert, but as a species, we thrive in community. And we suffer, when we don’t have that.

What can we do about it?

We can start by recognizing our needs, such as they are, and identifying to what extent they are being met (or not).

- Some of us may be very comfortable with a lot of alone time—but need someone to talk to sometimes.

- Some of us may need near-constant company to feel at our best—and that’s fine too! We just need to plan accordingly.

In the former case, it’s important to remember that needing someone to talk to is not being a burden to them. Not only will our company probably enrich them too, but also, we are evolved to care for one another, and that itself can bring fulfilment to them as much as to you. But what if you don’t a friend to talk to?

- You might be surprised at who would be glad of you reaching out. Have a think through whom you know, and give it a go. This can be scary, because what if they reject us, or worse, they don’t reject us but silently resent us instead? Again, they probably won’t. Human connection requires taking risks and being vulnerable sometimes.

- If that’s not an option, there are services that can fill your need. For some, therapy might serve a dual purpose in this regard. For others, you might want to check out the list of (mostly free) resources at the bottom of this article

In the second case (that we need near-constant company to feel at our best) we probably need to look more at our overall lifestyle, and find ways to be part of a community. That can include:

- Living in a close-knit community (places with a lot of retirees in one place often have this; or younger folk might look at communal living/working spaces, for example)

- Getting involved in local groups (you can check out NextDoor.com or MeetUp.com for this)

- Volunteering for a charity (not only are acts of service generally fulfilling in and of themselves, but also, you will probably be working with other people of a charitable nature, and such people tend to make for good company!)

Need a little help?

There are many, many organizations that will love to help you (or anyone else) overcome loneliness and isolation.

Rather than list them all here and make this email very long by describing how each of them works, here’s a great compilation of resources:

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Circadian Rhythm: Far More Than Most People Know

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Circadian Rhythm: Far More Than Most People Know

This is Dr. Satchidananda (Satchin) Panda, the scientist behind the discovery of the blue-light sensing cell type in the retina, and the many things it affects. But, he’s discovered more…

First, what you probably know (with a little more science)

Dr. Panda discovered that melanopsin, a photopigment, is “the primary candidate for photoreceptor-mediated entrainment”.

To put that in lay terms, it’s the brain’s go-to for knowing approximately what time of day or night it is, according to how much light there is (or isn’t), and how long it has (or hasn’t) been there.

But… the brain’s “go-to” isn’t the only method. By creating mice without melanopsin, he was able to find that they still keep a circadian rhythm, even in complete darkness:

Melanopsin (Opn4) Requirement for Normal Light-Induced Circadian Phase Shifting

In other words, it was a helpful, but not completely necessary, means of keeping a circadian rhythm.

So… What else is going on?

Dr. Panda and his team did a lot of science that is well beyond the scope of this main feature, but to give you an idea:

- With jargon: it explored the mechanisms and transcription translation negative feedback loops that regulate chronobiological processes, such as a histone lysine demathlyase 1a (JARID1a) that enhances Clock-Bmal1 transcription, and then used assorted genomic techniques to develop a model for how JARID1a works to moderate the level of Per transcription by regulating the transition between its repression and activation, and discovered that this heavily centered on hepatic gluconeogenesis and glucose homeostasis, facilitated by the protein cryptochrome regulating the fasting signal that occurs when glucagon binds to a G-protein coupled receptor, triggering CREB activation.

- Without jargon: a special protein tells our body how to respond to eating/fasting at different times of day—and conversely, certain physiological responses triggered by eating/fasting help us know what time of day it is.

- Simplest: our body keeps on its best cycle if we eat at the same time every day

This is important, because our circadian rhythm matters for a lot more than sleeping/waking! Take hormones, for example:

- Obvious hormones: testosterone and estrogen peak in the mornings around 9am, progesterone peaks between 10pm and 2am

- Forgotten hormones: cortisol peaks in the morning around 8:30am, melatonin peaks between 10pm and 2am

- More hormones: ghrelin (hunger hormone) peaks around 10am, leptin (satiety hormone) peaks 20 minutes after eating a certain amount of satiety-triggering food (protein does this most quickly), insulin is heavily tied to carbohydrate intake, but will still peak and trough according to when the body expects food.

What does this mean for us in practical terms?

For a start, it means that intermittent fasting can help guard against metabolic and related diseases (including inflammation, and thus also cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and more) a lot more if we practice it with our circadian rhythm in mind.

So that “8-hour window” for eating, that many intermittent fasting practitioners adhere to, is going to do much, much better if it’s 10am to 6pm, rather than, say, 4pm to midnight.

Additionally, Dr. Panda and his team found that a 12-hour eating window wasn’t sufficient to help significantly.

Some other take-aways:

- For reasons beyond the scope of this article, it’s good to exercise a) early b) before eating, so getting in some exercise between 8.30am and 10am is ideal

- It also means it’s beneficial to “front-load” eating, so a large breakfast at 10am, and smaller meals/snacks afterwards, is best.

- It also means that getting sunlight (even if cloud-covered) around 8.30am helps guard against metabolic disorders a lot, since the light remains the body’s go-to way of knowing the time.

- We realize that sunlight is not available at 8.30am at all latitudes at all times of year. Artificial is next-best.

- It also means sexual desire will typically peak in men in the mornings (per testosterone) and women in the evenings (per progesterone), but this is just an interesting bit of trivia, and not so relevant to metabolic health

What to do next…

Want to stabilize your own circadian rhythm in the best way, and also help Dr. Panda with his research?

His team’s (free!) app, “My Circadian Clock”, can help you track and organize all of the body’s measurable-by-you circadian events, and, if you give permission, will contribute to what will be the largest-yet human study into the topics covered today, to refine the conclusions and learn more about what works best.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

See what other 10almonds subscribers are asking!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Q: I would be interested in learning more about collagen and especially collagen supplements/powders and of course if needed, what is the best collagen product to take. What is collagen? Why do we need to supplement the collagen in our body? Thank you PS love the information I am receiving in the news letters. Keep it up

We’re glad you’re enjoying them! Your request prompted us to do our recent Research Review Monday main feature on collagen supplementation—we hope it helped, and if you’ve any more specific (or other) question, go ahead and let us know! We love questions and requests

Q: Great article about the health risks of salt to organs other than the heart! Is pink Himalayan sea salt, the pink kind, healthier?

Thank you! And, no, sorry. Any salt that is sodium chloride has the exact same effect because it’s chemically the same substance, even if impurities (however pretty) make it look different.

If you want a lower-sodium salt, we recommend the kind that says “low sodium” or “reduced sodium” or similar. Check the ingredients, it’ll probably be sodium chloride cut with potassium chloride. Potassium chloride is not only not a source of sodium, but also, it’s a source of potassium, which (unlike sodium) most of us could stand to get a little more of.

For your convenience: here’s an example on Amazon!

Bonus: you can get a reduced sodium version of pink Himalayan salt too!

Q: Can you let us know about more studies that have been done on statins? Are they really worth taking?

That is a great question! We imagine it might have been our recent book recommendation that prompted it? It’s quite a broad question though, so we’ll do that as a main feature in the near future!

Q: Is MSG healthier than salt in terms of sodium content or is it the same or worse?

Great question, and for that matter, MSG itself is a great topic for another day. But your actual question, we can readily answer here and now:

- Firstly, by “salt” we’re assuming from context that you mean sodium chloride.

- Both salt and MSG do contain sodium. However…

- MSG contains only about a third of the sodium that salt does, gram-for-gram.

- It’s still wise to be mindful of it, though. Same with sodium in other ingredients!

- Baking soda contains about twice as much sodium, gram for gram, as MSG.

Wondering why this happens?

Salt (sodium chloride, NaCl) is equal parts sodium and chlorine, by atom count, but sodium’s atomic mass is lower than chlorine’s, so 100g of salt contains only 39.34g of sodium.

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO₃) is one part sodium for one part hydrogen, one part carbon, and three parts oxygen. Taking each of their diverse atomic masses into account, we see that 100g of baking soda contains 27.4g sodium.

MSG (monosodium glutamate, C₅H₈NO₄Na) is only one part sodium for 5 parts carbon, 8 parts hydrogen, 1 part nitrogen, and 4 parts oxygen… And all those other atoms put together weigh a lot (comparatively), so 100g of MSG contains only 12.28g sodium.

Q: Thanks for the info about dairy. As a vegan, I look forward to a future comment about milk alternatives

Thanks for bringing it up! What we research and write about is heavily driven by subscriber feedback, so notes like this really help us know there’s an audience for a given topic!

We’ll do a main feature on it, to do it justice. Watch out for Research Review Monday!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What are heart rate zones, and how can you incorporate them into your exercise routine?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you spend a lot of time exploring fitness content online, you might have come across the concept of heart rate zones. Heart rate zone training has become more popular in recent years partly because of the boom in wearable technology which, among other functions, allows people to easily track their heart rates.

Heart rate zones reflect different levels of intensity during aerobic exercise. They’re most often based on a percentage of your maximum heart rate, which is the highest number of beats your heart can achieve per minute.

But what are the different heart rate zones, and how can you use these zones to optimise your workout?

The three-zone model

While there are several models used to describe heart rate zones, the most common model in the scientific literature is the three-zone model, where the zones may be categorised as follows:

- zone 1: 55%–82% of maximum heart rate

- zone 2: 82%–87% of maximum heart rate

- zone 3: 87%–97% of maximum heart rate.

If you’re not sure what your maximum heart rate is, it can be calculated using this equation: 208 – (0.7 × age in years). For example, I’m 32 years old. 208 – (0.7 x 32) = 185.6, so my predicted maximum heart rate is around 186 beats per minute.

There are also other models used to describe heart rate zones, such as the five-zone model (as its name implies, this one has five distinct zones). These models largely describe the same thing and can mostly be used interchangeably.

What do the different zones involve?

The three zones are based around a person’s lactate threshold, which describes the point at which exercise intensity moves from being predominantly aerobic, to predominantly anaerobic.

Aerobic exercise uses oxygen to help our muscles keep going, ensuring we can continue for a long time without fatiguing. Anaerobic exercise, however, uses stored energy to fuel exercise. Anaerobic exercise also accrues metabolic byproducts (such as lactate) that increase fatigue, meaning we can only produce energy anaerobically for a short time.

On average your lactate threshold tends to sit around 85% of your maximum heart rate, although this varies from person to person, and can be higher in athletes.

Wearable technology has taken off in recent years. Ketut Subiyanto/Pexels In the three-zone model, each zone loosely describes one of three types of training.

Zone 1 represents high-volume, low-intensity exercise, usually performed for long periods and at an easy pace, well below lactate threshold. Examples include jogging or cycling at a gentle pace.

Zone 2 is threshold training, also known as tempo training, a moderate intensity training method performed for moderate durations, at (or around) lactate threshold. This could be running, rowing or cycling at a speed where it’s difficult to speak full sentences.

Zone 3 mostly describes methods of high-intensity interval training, which are performed for shorter durations and at intensities above lactate threshold. For example, any circuit style workout that has you exercising hard for 30 seconds then resting for 30 seconds would be zone 3.

Striking a balance

To maximise endurance performance, you need to strike a balance between doing enough training to elicit positive changes, while avoiding over-training, injury and burnout.

While zone 3 is thought to produce the largest improvements in maximal oxygen uptake – one of the best predictors of endurance performance and overall health – it’s also the most tiring. This means you can only perform so much of it before it becomes too much.

Training in different heart rate zones improves slightly different physiological qualities, and so by spending time in each zone, you ensure a variety of benefits for performance and health.

So how much time should you spend in each zone?

Most elite endurance athletes, including runners, rowers, and even cross-country skiers, tend to spend most of their training (around 80%) in zone 1, with the rest split between zones 2 and 3.

Because elite endurance athletes train a lot, most of it needs to be in zone 1, otherwise they risk injury and burnout. For example, some runners accumulate more than 250 kilometres per week, which would be impossible to recover from if it was all performed in zone 2 or 3.

Of course, most people are not professional athletes. The World Health Organization recommends adults aim for 150–300 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week, or 75–150 minutes of vigorous exercise per week.

If you look at this in the context of heart rate zones, you could consider zone 1 training as moderate intensity, and zones 2 and 3 as vigorous. Then, you can use heart rate zones to make sure you’re exercising to meet these guidelines.

What if I don’t have a heart rate monitor?

If you don’t have access to a heart rate tracker, that doesn’t mean you can’t use heart rate zones to guide your training.

The three heart rate zones discussed in this article can also be prescribed based on feel using a simple 10-point scale, where 0 indicates no effort, and 10 indicates the maximum amount of effort you can produce.

With this system, zone 1 aligns with a 4 or less out of 10, zone 2 with 4.5 to 6.5 out of 10, and zone 3 as a 7 or higher out of 10.

Heart rate zones are not a perfect measure of exercise intensity, but can be a useful tool. And if you don’t want to worry about heart rate zones at all, that’s also fine. The most important thing is to simply get moving.

Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: