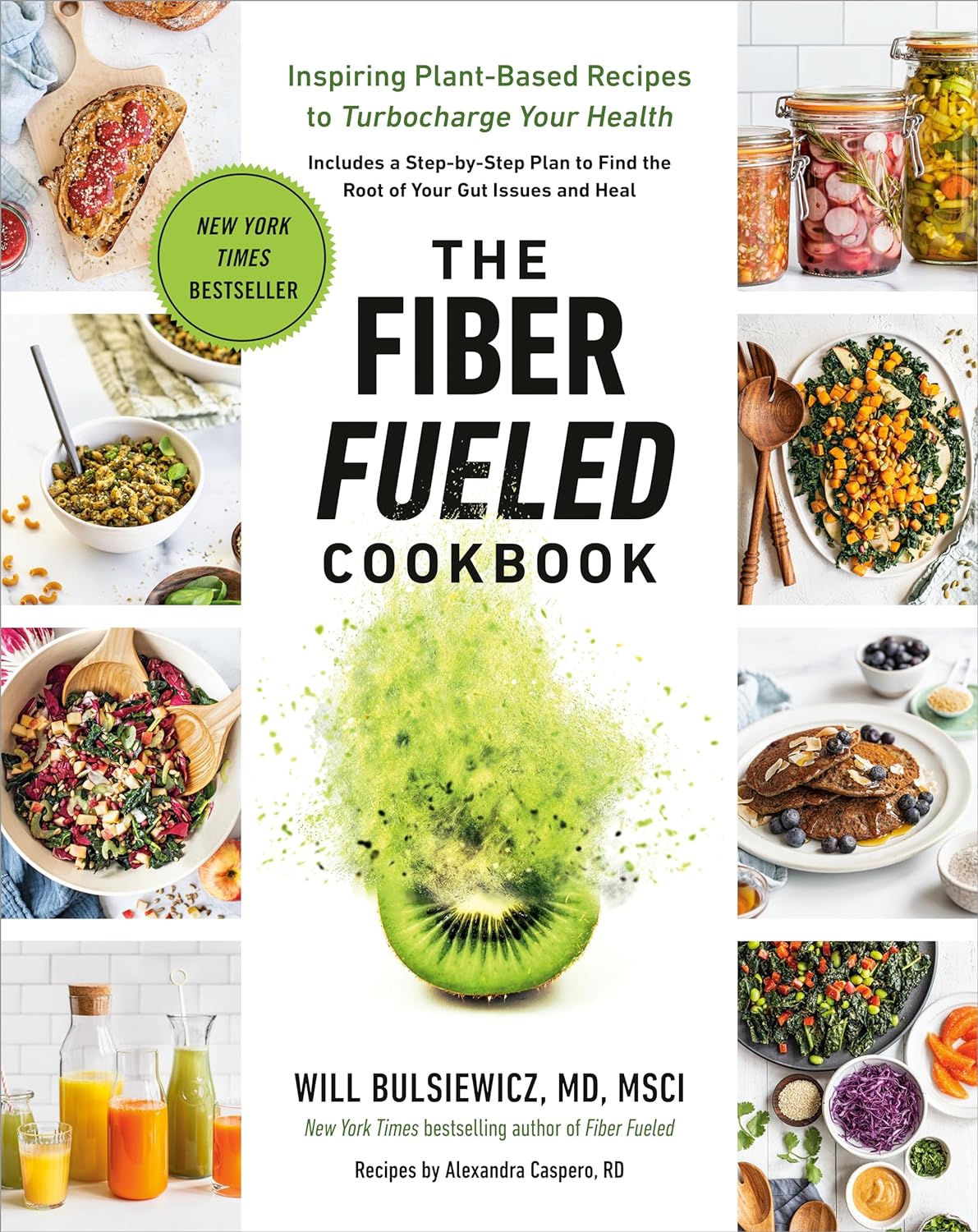

The Fiber Fueled Cookbook – by Dr. Will Bulsiewicz

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Dr. Bulsiewicz’s book “Fiber Fuelled” (which is great), but this one is more than just a cookbook with the previous book in mind. Indeed, this is even a great stand-alone book by itself, since it explains the core principles well enough already, and then adds to it.

It’s also about a lot more than just “please eat more fiber”, though. It looks at FODMAPs, purine, histamine intolerance, celiac disease, altered gallbladder function, acid reflux, and more.

He offers a five-part strategy:

Genesis (what is the etiology of your problem)

- Restrict (cut things out to address that first)

- Observe (keep a food/symptom diary)

- Work things back in (re-add potential triggers one by one, see how it goes)

- Train your gut (your microbiome does not exist in a vacuum, and communication is two-way)

- Holistic healing (beyond the gut itself, looking at other relevant factors and aiming for synergistic support)

As for the recipes themselves, there are more than a hundred of them and they are good, so no more “how can I possibly cook [favorite dish] without [removed ingredient]?”

Bottom line: if you’d like better gut health, this book is a top-tier option for fixing existing complaints, and enjoying plain-sailing henceforth.

Click here to check out The Fiber Fueled Cookbook; your gut will thank you later!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Exercise and Fat Loss (5 Things You Need To Know)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s easy to think “I’ll eat whatever; I can always burn it off later”, and if it’s an odd occasion, then that’s fine; indeed, a fit and healthy body can usually weather small infrequent dietary indiscretions easily. But…

You can’t outrun a bad diet

Exercise can create a calorie deficit, but over time, the body balances this out by adjusting one’s metabolism, leading to a plateau in fat loss—and as you might know, you can’t out-exercise a bad diet. On the contrary, dietary adjustments are crucial for fat loss and body recomposition.

About that calorie deficit in the first place, by the way: extreme calorie deficits through exercise alone can lead to muscle loss, reduced energy, and thus sabotage long-term fat loss because having muscle mass increases one’s base metabolic rate (while having fat does not).

Another thing to bear in mind about exercise is that longer workouts without adequate rests in between can cause burnout, injury, or weight gain due to the body doing its best to conserve energy.

So, a good diet is a necessary condition for both muscle maintenance and fat loss.

Five Key Diet Tips:

- Include foods you love: don’t feel obliged cut out favorite foods that are a little unhealthy; incorporate them in moderation for sustainability.

- Keep adjustments small: avoid making drastic dietary changes all at once; make gradual tweaks to prevent feeling deprived.

- Prioritize protein: focus on including a protein source in every meal to increase satiety and aid in muscle building.

- Avoid low-calorie diets: drastically cutting calories can lead to muscle loss, metabolic adaptation, and overeating.

- Embrace diet evolution: changes may not feel sustainable at first, but adjustments over time help achieve long-term balance. You can always “adjust course” as you go.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Are You A Calorie-Burning Machine?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Dancing vs Parkinson’s Depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a fun study, and the results are/were very predictable, and/but not necessarily something that people might think of in advance. First, let’s look at how some things work:

Parkinson’s disease & depression

Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative neurological disease that, amongst other things, is characterized by low dopamine levels.

For the general signs and symptoms, see: Recognize The Early Symptoms Of Parkinson’s Disease

Dopamine is the neurotransmitter responsible for feelings of reward, is involved in our language faculties and the capacity to form plans (even simple plans such as “make a cup of coffee”) as well as being critical for motor functions.

See also: Neurotransmitter Cheatsheet ← for demystifying some of “what does what” for commonly-conflated chemicals

You can see, therefore, why Parkinson’s disease will often have depression as a comorbidity—there may be influencing social factors as well (many Parkinson’s disease sufferers are quite socially isolated, which certainly does not help), but a clear neurochemical factor that we can point to is “a person with low dopamine levels will feel joyless, bored, and unmotivated”.

Let movement be thy medicine

Parkinson’s disease medications, therefore, tend to involve increasing dopamine levels and/or the brain’s ability to use dopamine.

Antidepressant medications, however, are more commonly focused on serotonin, as serotonin is another neurotransmitter associated with happiness—it’s the one we get when we look at open green spaces with occasional trees and a blue sky ← we get it in other ways too, but for evolutionary reasons, it seems our brains still yearn the most for landscapes that look like the Serengeti, even if we have never even been there personally.

There are other kinds of antidepressants too, and (because depression can have different causes) what works for one person won’t necessarily work for another. See: Antidepressants: Personalization Is Key!

In the case of Parkinson’s disease, because the associated depression is mostly dopamine-related, those green spaces and blue skies and SSRIs won’t help much. But you know what does?

Dance!

A recent (published last month, at time of writing) study by Dr. Karolina Bearss et al. did an interventional study that found that dance classes significantly improved both subjective experience of depression, and objective brain markers of depression, across people with (68%) and without (32%) Parkinson’s disease.

The paper is quite short and it has diagrams, and discusses the longer-term effect as well as the per-session effect:

Dance is thought to have a double-effect, improving both cognitive factors and motor control factors, for obvious reasons, and all related to dopamine response (dancing is an activity we are hardwired to find rewarding*, plus it is exercise which also triggers various chemicals to be made, plus it is social, which also improves many mental health factors).

*You may have heard the expression that “dancing is a vertical expression of a horizontal desire”, and while that may not be true for everyone on an individual level, on a species level it is a very reasonable hypothesis for why we do it and why it is the way it is.

Want to learn more?

We wrote previously about battling depression (of any kind) here:

The Mental Health First-Aid That You’ll Hopefully Never Need

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Jasmine McDonald’s Ballet Stretching Routine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Why Jasmine’s Video is Useful

Jasmine McDonald is not only a professional ballerina, but is also a certified personal trainer, so when it comes to keeping her body strong and flexible, she’s a wealth of knowledge. Her video (below) is a great example of this.

In case you’re interested in learning more, she currently (privately) tutors over 30 people on a day-to-day basis. You can contact her here!

Other Stretches?

If you think that Jasmine’s stretches may be out of your league, we recommend checking out our other articles on stretching, including:

- 11 Minutes to Pain-Free Hips

- How to Permanently Loosen a Tight Psoas

- Stretching Scientifically

- Stretching & Mobility

- Stretching to Stay Young

Otherwise, let loose on these dancer stretches and exercises:

How did you find that video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Your Heart In Their Hands: Surgeon Preferences & Survival Rates

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Unless you are paying entirely out-of-pocket for a heart surgery, you will not usually get final say over which surgeon you get.

The surgeon, however, will have final say over what they actually do when they open you up.

And their preferences, it seems, can make all the difference:

MAG vs SAG

When doing coronary artery bypass grafting, (CABG), surgeons may prefer to do multi-arterial grafting (MAG) or single-arterial grafting (SAG).

Recently, there was a study analysing more than a million Americans who underwent CABG on Medicare over an 18-year period, looking at outcomes for MAG vs SAG.

The superficial news: those who received MAG had much better long-term survival chances than those who received SAG.

However: this may be less to do with the relative merits of the procedures themselves, and more to do with the preferences of the surgeon.

The “eyeball test”

If surgeons look at a patient and think they will not have many years to live after surgery, they may opt for the SAG, as the long-term benefits of the MAG will only manifest in the long-term.

This may seem a little self-defeating (indeed, maybe you won’t live to see the long-term if you don’t get the surgery type with the longer-term survival chances), there can be other factors involved, that may make surgeons more interested in your short-term survival chances.

Or you might just not have enough donor artery tissue available to pick and choose; after all, a person having a coronary artery bypass quite possibly won’t have great arteries in their arm or leg, either.

Or a person could be missing limbs (a common complication, given the comorbidities of both peripheral artery disease, and diabetes).

See also: How To Stay A Step Ahead Of Peripheral Artery Disease

Why it might be ok that things are like this

When factoring in surgeon preference for MAG or SAG as an instrumental variable, no significant difference in long-term survival was observed. This may explain inconsistencies with randomized controlled trials like the Arterial Revascularization Trial (ART), which also found no survival benefit of MAG over SAG.

Also, MAG recipients were generally younger, healthier, and from more resourceful areas, which likely had a further impact on MAG-giving decisions, and/but at the same time, may also have increased survival chances for reasons other than that they got MAG rather than SAG.

Here’s a pop-science article that goes into more detail about this:

Surgeon preferences may explain differences in CABG survival rates

How to look out for yourself, and advocate for yourself

…or your loved one, of course. Now, having a coronary artery bypass surgery of any kind is not a fun activity; it will be dangerous, it’ll be stressful before and after, and the recovery will often not be an easy time either. However, it is possible to learn more about what is going on / what will happen, ask the right questions, and get the best options for you (which may not always be the same as the best options for someone else).

We wrote about that in more detail here:

Nobody Likes Surgery, But Here’s How To Make It Much Less Bad

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can Ginkgo Tea Be Made Safe? (And Other Questions)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I’d be interested in OTC prostrate medication safety and effectiveness.❞

Great idea! Sounds like a topic for a main feature one day soon, but while you’re waiting, you might like this previous main feature we did, about a supplement that performs equally to some prescription BPH meds:

❝Was very interested in the article on ginko bilboa as i moved into a home that has the tree growing in the backyard. Is there any way i can process the leaves to make a tea out of it.❞

Glad you enjoyed! First, for any who missed it, here was the article on Ginkgo biloba:

Ginkgo Biloba, For Memory And, Uh, What Else Again?

Now, as that article noted, Ginkgo biloba seeds and leaves are poisonous. However, there are differences:

The seeds, raw or roasted, contain dangerous levels of a variety of toxins, though roasting takes away some toxins and other methods of processing (boiling etc) take away more. However, the general consensus on the seeds is “do not consume; it will poison your liver, poison your kidneys, and possibly give you cancer”:

Ginkgo biloba L. seed; A comprehensive review of bioactives, toxicants, and processing effects

The leaves, meanwhile, are much less poisonous with their ginkgolic acids, and their other relevant poison is very closely related to that of poison ivy, involving long-chain alkylphenols that can be broken down by thermolysis, in other words, heat:

However, this very thorough examination of the potential health benefits and risks of ginkgo tea, comes to the general conclusion “this is not a good idea, and is especially worrying in elders, and/or if taking various medications”:

In summary:

- Be careful

- Avoid completely if you have a stronger-than-usual reaction to poison ivy

- If you do make tea from it, green leaves appear to be safer than yellow ones

- If you do make tea from it, boil and stew to excess to minimize toxins

- If you do make tea from it, doing a poison test is sensible (i.e. start with checking for a skin reaction to a topical application on the inside of the wrist, then repeat at least 6 hours later on the lips, then at least 6 hours later do a mouth swill, then at least 12 hours later drink a small amount, etc, and gradually build up to “this is safe to consume”)

For safety (and legal) purposes, let us be absolutely clear that we are not advising you that it is safe to consume a known poisonous plant, and nor are we advising you to do so.

But the hopefully only-ever theoretical knowledge of how to do a poison test is a good life skill, just in case

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Nudge – by Richard Thaler & Cass Sunstein

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How often in life do we make a suboptimal decision that ends up plaguing us for a long time afterwards? Sometimes, a single good or bad decision can even directly change the rest of our life.

So, it really is important that we try to optimize the decisions we do make.

Professors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein look at all kinds of decision-making in this book. Their goal, as per the subtitle, is “improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness”.

For the most part, the book concentrates on “nudges”. Small factors that influence our decisions one way or another.

Most importantly: that some of them are very good reasons to be nudged; others, very bad ones. And they often look similar.

Where this book excels is in highlighting the many ways we make decisions without even thinking about it… or we think about it, but only down a prescribed, foreseen track, to an externally expected conclusion (for example, an insurance company offering three packages, but two of them exist only to direct you to the “correct” choice).

A weakness of the book is that in some aspects it’s a little inconsistent. The authors describe their economic philosophy as “libertarian paternalism”, and as libertarians they’re against mandates, except when as paternalists they’re for them. But, if we take away their labels, this boils down to “some mandates can be good and some can be bad”, which would not be so inconsistent after all.

Bottom line: if you’d like to better understand your own decision-making processes through the eyes of policy-setting economists (especially Sunstein, who worked for the White House Office of Information & Regulatory Affairs) whose job it is to make sure you make the “right” decisions, then this is a very enlightening book.

Click here to check out Nudge and improve your decision-making clarity!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: