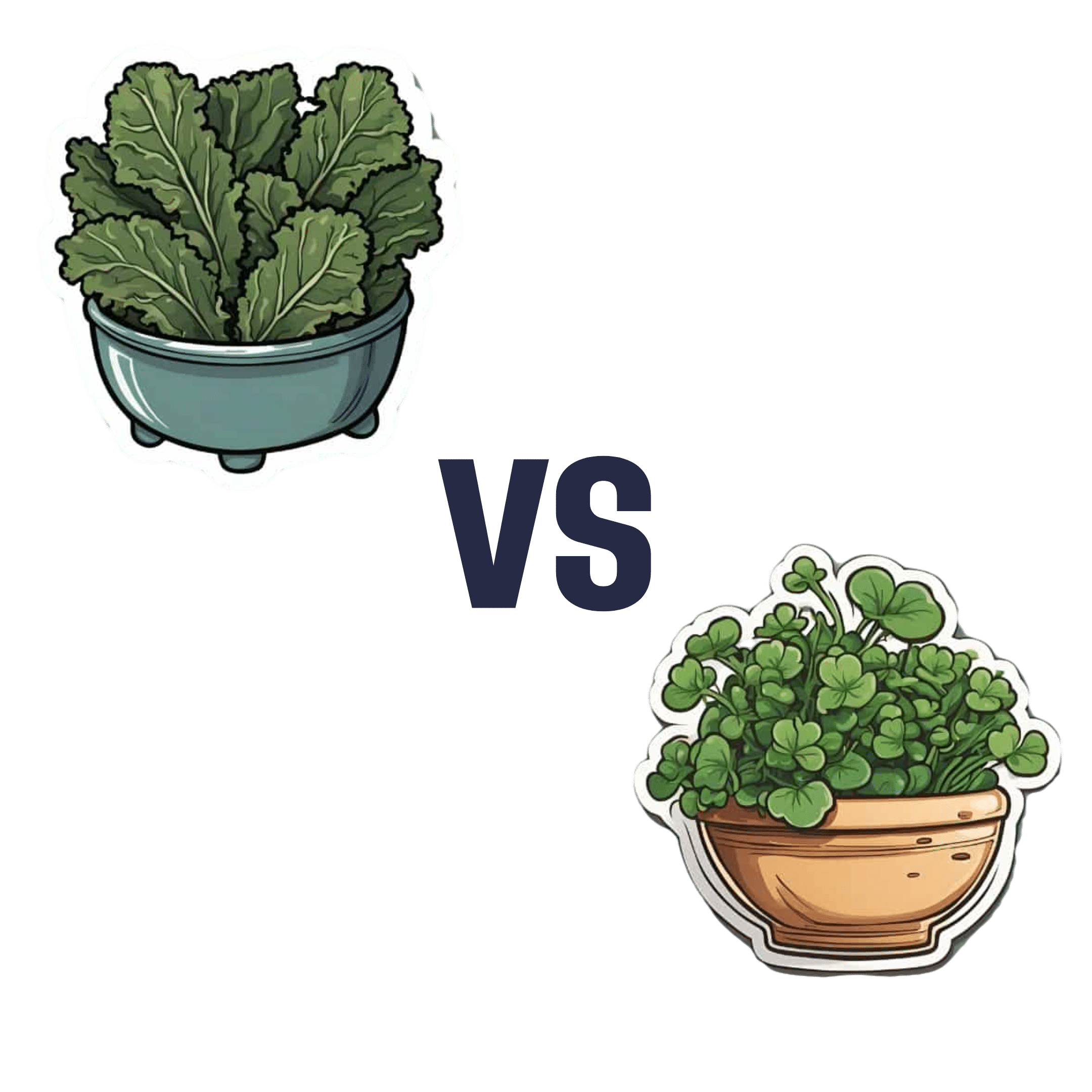

Spinach vs Kale – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing spinach to kale, we picked the spinach.

Why?

In terms of macros, spinach and kale are very similar. They are mostly water wrapped in fiber, with very small amounts of carbohydrates and protein and trace amounts of fat.

Spinach has a lot more vitamins and minerals—a wider variety, and in most cases, more of them.

Kale is notably higher in vitamin C, though. Everything else, spinach is higher or close to equal.

Spinach is especially notably a lot higher in B vitamins, as well as iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc.

One downside to spinach, though, which is that it’s high in oxalates, which can increase the risk of kidney stones. If your kidneys are in good health and you eat spinach in moderation, this is not a problem for most people—but if your kidneys aren’t in good health (or you are, for whatever reason, consuming Popeye levels of spinach), you might consider switching to kale.

While spinach swept the board in most categories, kale remains a very good option too, and a diet diverse in many kinds of plants is usually best.

Want to learn more?

Spinach and kale are very both good sources of carotenoids; check out:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Non-Sleep Deep Rest: A Neurobiologist’s Take

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How to get many benefits of sleep, while awake!

Today we’re talking about Dr. Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist and professor in the department of neurobiology at Stanford School of Medicine.

He’s also a popular podcaster, and as his Wikipedia page notes:

❝In episodes lasting several hours, Huberman talks about the state of research in a specific topic, both within and outside his specialty❞

Today, we won’t be taking hours, and we will be taking notes from within his field of specialty (neurobiology). Specifically, in this case:

Non-Sleep Deep Rest (NSDR)

What is it? To quote from his own dedicated site on the topic:

❝What is NSDR (Yoga Nidra)? Non-Sleep Deep Rest, also known as NSDR, is a method of deep relaxation developed by Dr. Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist at Stanford University School of Medicine.

It’s a process that combines controlled breathing and detailed body scanning to bring you into a state of heightened awareness and profound relaxation. The main purpose of NSDR is to reduce stress, enhance focus, and improve overall well-being.❞

While it seems a bit bold of Dr. Huberman to claim that he developed yoga nidra, it is nevertheless reassuring to get a neurobiologist’s view on this:

How it works, by science

Dr. Huberman says that by monitoring EEG readings during NSDR, we can see how the brain slows down. Measurably!

- It goes from an active beta range of 13–30 Hz (normal waking) to a conscious meditation state of an alpha range of 8–13 Hz.

- However, with practice, it can drop further, into a theta range of 4–8 Hz.

- Ultimately, sustained SSDR practice can get us to 0.5–3 Hz.

This means that the brain is functioning in the delta range, something that typically only occurs during our deepest sleep.

You may be wondering: why is delta lower than theta? That’s not how I remember the Greek alphabet being ordered!

Indeed, while the Greek alphabet goes alpha beta gamma delta epsilon zeta eta theta (and so on), the brainwave frequency bands are:

- Gamma = concentrated focus, >30 Hz

- Beta = normal waking, 13–30 Hz

- Alpha = relaxed state, 8–13 Hz

- Theta = light sleep, 4–8 Hz

- Delta = deep sleep, 1–4 Hz

Source: Sleep Foundation ← with a nice infographic there too

NSDR uses somatic cues to engage our parasympathetic nervous system, which in turn enables us to reach those states. The steps are simple:

- Pick a time and place when you won’t be disturbed

- Lie on your back and make yourself comfortable

- Close your eyes as soon as you wish, and now that you’ve closed them, imagine closing them again. And again.

- Slowly bring your attention to each part of your body in turn, from head to toe. As your attention goes to each part, allow it to relax more.

- If you wish, you can repeat this process for another wave, or even a third.

- Find yourself well-rested!

Note: this engagement of the parasympathetic nervous system and slowing down of brain activity accesses restorative states not normally available while waking, but 10 minutes of NSDR will not replace 7–9 hours of sleep; nor will it give you the vital benefits of REM sleep specifically.

So: it’s an adjunct, not a replacement

Want to try it, but not sure where/how to start?

When you’re ready, let Dr. Huberman himself guide you through it in this shortish (10:49) soundtrack:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to try it, but not right now? Bookmark it for later

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

Piperine, a compound found in Piper nigrum (black pepper, to its friends), has many health benefits. It’s included as a minor ingredient in some other supplements, because it boosts bioavailability. In its form as a kitchen spice, it’s definitely a superfood.

What does it do?

First, three things that generally go together:

These things often go together for the simple reason that oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer often go together. In each case, it’s a matter of cellular wear-and-tear, and what can mitigate that.

For what it’s worth, there’s generally a fourth pillar: anti-aging. This is again for the same reason. That said, black pepper hasn’t (so far as we could find) been studied specifically for its anti-aging properties, so we can’t cite that here as an evidence-based claim.

Nevertheless, it’s a reasonable inference that something that fights oxidation, inflammation, and cancer, will often also slow aging.

Special note on the anti-cancer properties

We noticed two very interesting things while researching piperine’s anti-cancer properties. It’s not just that it reduces cancer risk and slows tumor growth in extant cancers (as we might expect from the above-discussed properties). Let’s spotlight some studies:

It is selectively cytotoxic (that’s a good thing)

Piperine was found to be selectively cytotoxic to cancerous cells, while not being cytotoxic to non-cancerous cells. To this end, it’s a very promising cancer-sniper:

Piperine as a Potential Anti-cancer Agent: A Review on Preclinical Studies

It can reverse multi-drug resistance in cancer cells

P-glycoprotein, found in our body, is a drug-transporter that is known for “washing out” chemotherapeutic drugs from cancer cells. To date, no drug has been approved to inhibit P-glycoprotein, but piperine has been found to do the job:

Targeting P-glycoprotein: Investigation of piperine analogs for overcoming drug resistance in cancer

What’s this about piperine analogs, though? Basically the researchers found a way to “tweak” piperine to make it even more effective. They called this tweaked version “Pip1”, because calling it by its chemical name,

((2E,4E)-5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1-(6,7-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1 H)-yl)penta-2,4-dien-1-one)

…got a bit unwieldy.

The upshot is: Pip1 is better, but piperine itself is also good.

Other benefits

Piperine does have other benefits too, but the above is what we were most excited to talk about today. Its other benefits include:

- Neuroprotective effects (against Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and more)

- Blood-sugar balancing / antidiabetic effect

- Good for gut microbiome diversity

- Heart health benefits, including cholesterol-balancing

- Boosts bioavailability of other nutrients/drugs

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

How To Reduce Chronic Stress

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sunday Stress-Buster

First, an important distinction:

- Acute stress (for example, when stepping out of your comfort zone, engaging in competition, or otherwise focusing on something that requires your full attention for best performance) is generally a good thing. It helps you do you your best. It’s sometimes been called “eustress”, “good stress”.

- Chronic stress (for example, when snowed under at work and you do not love it, when dealing with a serious illness, and/or faced with financial problems) is unequivocally a bad thing. Our body is simply not made to handle that much cortisol (the stress hormone) all the time.

Know the dangers of too much cortisol

We covered this as a main feature last month: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

…but it bears mentioning again and for those who’ve joined us since then:

A little spike of cortisol now and again can be helpful. Having it spiking all the time, or even a perpetual background low-to-moderate level, can be ruinous to the health in so many ways.

The good news is, the physiological impact of stress on the body (which ranges from face-and-stomach fat deposits, to rapid aging), can be reversed—even the biological aging!

Read: Biological age is increased by stress and restored upon recovery ← this study is so hot-of-the-press that it was published literally two days ago

Focus on what you can control

A lot of things that cause you stress may be outside of your control. Focus on what is within your control. Oftentimes, we are so preoccupied with the stress, that we employ coping strategies that don’t actually deal with the problem.

That’s a maladaptive response to an evolutionary quirk—our bodies haven’t caught up with modern life, and on an evolutionary scale, are still priming us to deal with sabre-toothed tigers, not financial disputes, for example.

But, how to deal with the body’s “wrong” response?

First, deal with the tiger. There isn’t one, but your body doesn’t know that. Do some vigorous exercise, or if that’s not your thing, tense up your muscles strongly for a few seconds and then relax them, doing each part of your body. This is called progressive relaxation, and how it works is basically tricking your body into thinking you successfully fled the tiger, or fought the tiger and won.

Next, examine what the actual problem is, that’s causing you stress. You’re probably heavily emotionally attached to the problem, or else it wouldn’t be stressing you. So, imagine what advice you would give to help a friend deal with the same problem, and then do that.

Better yet: enlist an actual friend (or partner, family member, etc) to help you. We are evolved to live in a community, engaged in mutual support. That’s how we do well; that’s how we thrive best.

By dealing with the problem—or sometimes even just having support and/or something like a plan—your stress will evaporate soon enough.

The power of “…and then what?”

Sometimes, things are entirely out of your control. Sometimes, bad things are entirely possible; perhaps even probable. Sometimes, they’re so bad, that it’s difficult to avoid stressing about the possible outcomes.

If something seems entirely out of your control and/or inevitable, ask yourself:

“…and then what?”

Writer’s storytime: when I was a teenager, sometimes I would go out without a coat, and my mother would ask, pointedly, “But what will you do if it rains?!”

I’d reply “I’ll get wet, of course”

This attitude can go just the same for much more serious outcomes, up to and including death.

So when you find yourself stressing about some possible bad outcome, ask yourself, “…and then what?”.

- What if this is cancer? Well, it might be. And then what? You might seek cancer treatment.

- What if I can’t get treatment, or it doesn’t work? Well, you might die. And then what?

In Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT), this is called “radical acceptance” and acknowledges bad possible/probable/known outcomes, allows one to explore the feelings, and come up with a plan for managing the situation, or even just coming to terms with the fact that sometimes, suffering is inevitable and is part of the human condition.

It’ll still be bad—but you won’t have added extra suffering in the form of stress.

Breathe.

Don’t underestimate the power of relaxed deep breathing to calm the rest of your body, including your brain.

Also: we’ve shared this before, a few months ago, but this 8 minute soundscape was developed by sound technicians working with a team of psychologists and neurologists. It’s been clinically tested, and found to have a much more relaxing effect(in objective measures of lowering heart rate and lowering cortisol levels, as well as in subjective self-reports) than merely “relaxing music”.

Try it and see for yourself:

! Share This Post

Related Posts

-

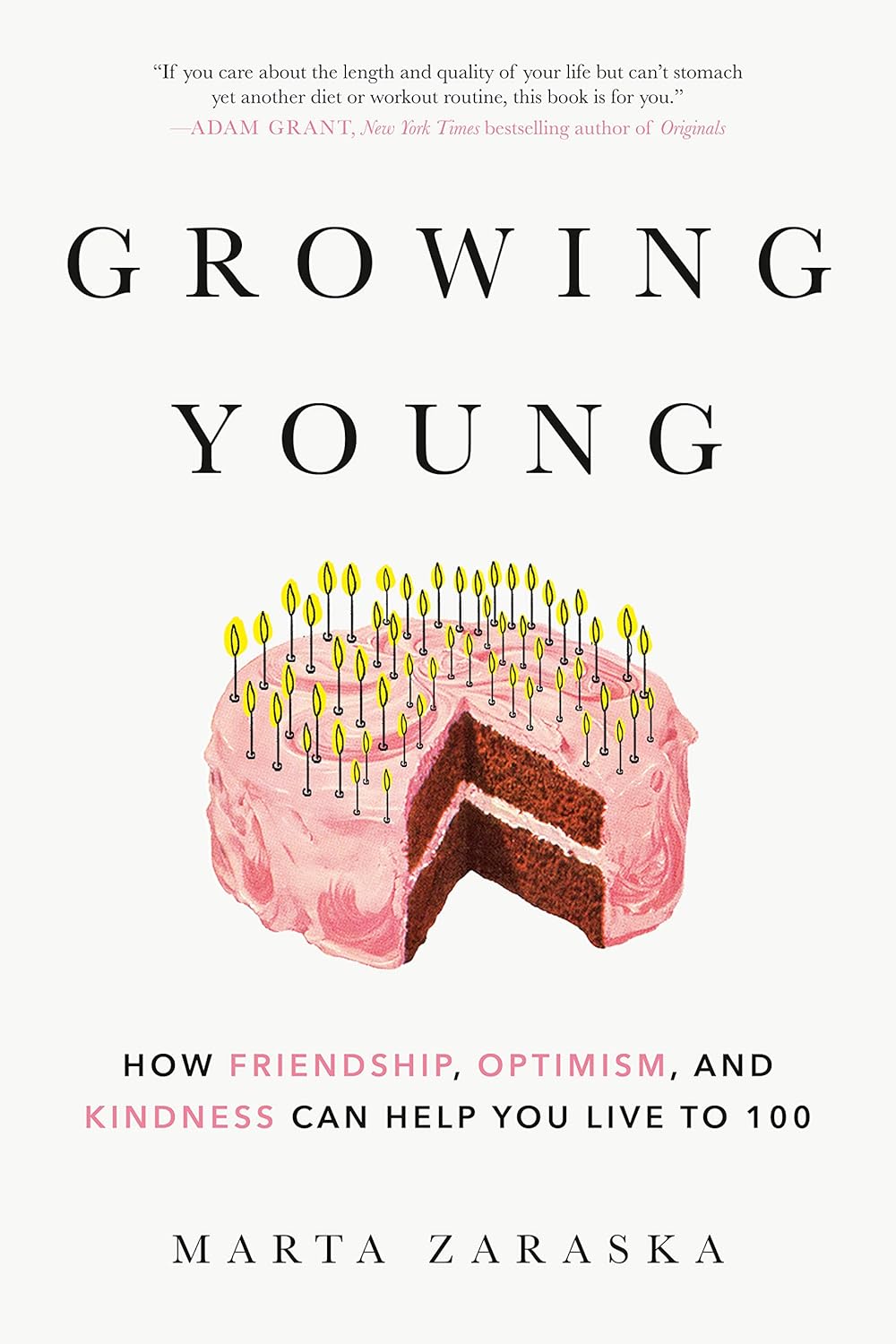

Growing Young – by Marta Zaraska

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one will be a slightly mixed review, but we think the book has more than enough of value to make it a very worthwhile read.

The premise of the book is that, as the subtitle suggests, positive social qualities increase personal longevity.

Author (and science journalist) Marta Zaraska looks at a lot of research to back this up, and also did a lot of travelling and digging into stories. This is of great value, because she notes where a lot of misconceptions have arisen.

To give one example, it’s commonly noted that marriage (or as-though-marriage life partnerships) is generally* associated with longer life.

*Statistics suggest that marriage-related longevity is enjoyed by men married to women, and people in same-sex marriages regardless of gender, but is not so much the case for women married to men.

However! Zaraska notes a factor she learned from Gottman’s research (yes, that Gottman), that what matters is not the official status of a relationship, so much as the sense of secure lifelong commitment to it.

These kinds of observations (throughout the book) add an extra layer beyond “common wisdom”, and allow us to better understand what’s really going on. The book’s main weaknesses, meanwhile, are twofold:

- The author is (in this reviewer’s opinion) unduly dismissive of physical health lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise, because they “only” account for a similar bonus to healthy longevity.

- Like many, she does not always consider where correlation might not mean causation. For example, she cites that volunteering free time increases healthspan by 22%, but neglects to note that perhaps it is having the kind of socioeconomic situation that allows one free time to volunteer, that gives the benefit.

Bottom line: the book has its flaws, but we think that only serves to make it more engaging. After all, reading should not be a purely passive activity! Zaraska’s well-studied insights give plenty of pointers for tweaking the social side of anyone’s quest for healthy longevity.

Click here to check out Growing Young, increase your healthspan, and take joy in doing it!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is a ‘vaginal birth after caesarean’ or VBAC?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A vaginal birth after caesarean (known as a VBAC) is when a woman who has had a caesarean has a vaginal birth down the track.

In Australia, about 12% of women have a vaginal birth for a subsequent baby after a caesarean. A VBAC is much more common in some other countries, including in several Scandinavian ones, where 45-55% of women have one.

So what’s involved? What are the risks? And who’s most likely to give birth vaginally the next time round?

MVelishchuk/Shutterstock What happens? What are the risks?

When a woman chooses a VBAC she is cared for much like she would during a planned vaginal birth.

However, an induction of labour is avoided as much as possible, due to the slightly increased risk of the caesarean scar opening up (known as uterine rupture). This is because the medication used in inductions can stimulate strong contractions that put a greater strain on the scar.

In fact, one of the main reasons women may be recommended to have a repeat caesarean over a vaginal birth is due to an increased chance of her caesarean scar rupturing.

This is when layers of the uterus (womb) separate and an emergency caesarean is needed to deliver the baby and repair the uterus.

Uterine rupture is rare. It occurs in about 0.2-0.7% of women with a history of a previous caesarean. A uterine rupture can also happen without a previous caesarean, but this is even rarer.

However, uterine rupture is a medical emergency. A large European study found 13% of babies died after a uterine rupture and 10% of women needed to have their uterus removed.

The risk of uterine rupture increases if women have what’s known as complicated or classical caesarean scars, and for women who have had more than two previous caesareans.

Most care providers recommend you avoid getting pregnant again for around 12 months after a caesarean, to allow full healing of the scar and to reduce the risk of the scar rupturing.

National guidelines recommend women attempt a VBAC in hospital in case emergency care is needed after uterine rupture.

During a VBAC, recommendations are for closer monitoring of the baby’s heart rate and vigilance for abnormal pain that could indicate a rupture is happening.

If labour is not progressing, a caesarean would then usually be advised.

Giving birth in hospital is recommended for a vaginal birth after a caesarean. christinarosepix/Shutterstock Why avoid multiple caesareans?

There are also risks with repeat caesareans. These include slower recovery, increased risks of the placenta growing abnormally in subsequent pregnancies (placenta accreta), or low in front of the cervix (placenta praevia), and being readmitted to hospital for infection.

Women reported birth trauma and post-traumatic stress more commonly after a caesarean than a vaginal birth, especially if the caesarean was not planned.

Women who had a traumatic caesarean or disrespectful care in their previous birth may choose a VBAC to prevent re-traumatisation and to try to regain control over their birth.

We looked at what happened to women

The most common reason for a caesarean section in Australia is a repeat caesarean. Our new research looked at what this means for VBAC.

We analysed data about 172,000 low-risk women who gave birth for the first time in New South Wales between 2001 and 2016.

We found women who had an initial spontaneous vaginal birth had a 91.3% chance of having subsequent vaginal births. However, if they had a caesarean, their probability of having a VBAC was 4.6% after an elective caesarean and 9% after an emergency one.

We also confirmed what national data and previous studies have shown – there are lower VBAC rates (meaning higher rates of repeat caesareans) in private hospitals compared to public hospitals.

We found the probability of subsequent elective caesarean births was higher in private hospitals (84.9%) compared to public hospitals (76.9%).

Our study did not specifically address why this might be the case. However, we know that in private hospitals women access private obstetric care and experience higher caesarean rates overall.

What increases the chance of success?

When women plan a VBAC there is a 60-80% chance of having a vaginal birth in the next birth.

The success rates are higher for women who are younger, have a lower body mass index, have had a previous vaginal birth, give birth in a home-like environment or with midwife-led care.

For instance, an Australian study found women who accessed continuity of care with a midwife were more likely to have a successful VBAC compared to having no continuity of care and seeing different care providers each time.

An Australian national survey we conducted found having continuity of care with a midwife when planning a VBAC can increase women’s sense of control and confidence, increase their chance to be upright and active in labour and result in a better relationship with their health-care provider.

Seeing the same midwife throughout your maternity care can help. Tyler Olson/Shutterstock Why is this important?

With the rise of caesareans globally, including in Australia, it is more important than ever to value vaginal birth and support women to have a VBAC if this is what they choose.

Our research is also a reminder that how a woman gives birth the first time greatly influences how she gives birth after that. For too many women, this can lead to multiple caesareans, not all of them needed.

Hannah Dahlen, Professor of Midwifery, Associate Dean Research and HDR, Midwifery Discipline Leader, Western Sydney University; Hazel Keedle, Senior Lecturer of Midwifery, Western Sydney University, and Lilian Peters, Adjunct Research Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Could my glasses be making my eyesight worse?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

So, you got your eyesight tested and found out you need your first pair of glasses. Or you found out you need a stronger pair than the ones you have. You put them on and everything looks crystal clear. But after a few weeks things look blurrier without them than they did before your eye test. What’s going on?

Some people start to wear spectacles for the first time and perceive their vision is “bad” when they take their glasses off. They incorrectly interpret this as the glasses making their vision worse. Fear of this might make them less likely to wear their glasses.

But what they are noticing is how much better the world appears through the glasses. They become less tolerant of a blurry world when they remove them.

Here are some other things you might notice about eyesight and wearing glasses.

Lazy eyes?

Some people sense an increasing reliance on glasses and wonder if their eyes have become “lazy”.

Our eyes work in much the same way as an auto-focus camera. A flexible lens inside each eye is controlled by muscles that let us focus on objects in the distance (such as a footy scoreboard) by relaxing the muscle to flatten the lens. When the muscle contracts it makes the lens steeper and more powerful to see things that are much closer to us (such as a text message).

From the age of about 40, the lens in our eye progressively hardens and loses its ability to change shape. Gradually, we lose our capacity to focus on near objects. This is called “presbyopia” and at the moment there are no treatments for this lens hardening.

Optometrists correct this with prescription glasses that take the load of your natural lens. The lenses allow you to see those up-close images clearly by providing extra refractive power.

Once we are used to seeing clearly, our tolerance for blurry vision will be lower and we will reach for the glasses to see well again.

The wrong glasses?

Wearing old glasses, the wrong prescription (or even someone else’s glasses) won’t allow you to see as well as possible for day-to-day tasks. It could also cause eyestrain and headaches.

Incorrectly prescribed or dispensed prescription glasses can lead to vision impairment in children as their visual system is still in development.

But it is more common for kids to develop long-term vision problems as a result of not wearing glasses when they need them.

By the time children are about 10–12 years of age, wearing incorrect spectacles is less likely to cause their eyes to become lazy or damage vision in the long term, but it is likely to result in blurry or uncomfortable vision during daily wear.

Registered optometrists in Australia are trained to assess refractive error (whether the eye focuses light into the retina) as well as the different aspects of ocular function (including how the eyes work together, change focus, move around to see objects). All of these help us see clearly and comfortably.

Younger children with progressive vision impairments may need more frequent eye tests. Shutterstock What about dirty glasses?

Dirty or scratched glasses can give you the impression your vision is worse than it actually is. Just like a window, the dirtier your glasses are, the more difficult it is to see clearly through them. Cleaning glasses regularly with a microfibre lens cloth will help.

While dirty glasses are not commonly associated with eye infections, some research suggests dirty glasses can harbour bacteria with the remote but theoretical potential to cause eye infection.

To ensure best possible vision, people who wear prescription glasses every day should clean their lenses at least every morning and twice a day where required. Cleaning frames with alcohol wipes can reduce bacterial contamination by 96% – but care should be taken as alcohol can damage some frames, depending on what they are made of.

When should I get my eyes checked?

Regular eye exams, starting just before school age, are important for ocular health. Most prescriptions for corrective glasses expire within two years and contact lens prescriptions often expire after a year. So you’ll need an eye check for a new pair every year or so.

Kids with ocular conditions such as progressive myopia (short-sightedness), strabismus (poor eye alignment), or amblyopia (reduced vision in one eye) will need checks at least every year, but likely more often. Likewise, people over 65 or who have known eye conditions, such as glaucoma, will be recommended more frequent checks.

Eye checks can detect broader health issues. Shutterstock An online prescription estimator is no substitute for a full eye examination. If you have a valid prescription then you can order glasses online, but you miss out on the ability to check the fit of the frame or to have them adjusted properly. This is particularly important for multifocal lenses where even a millimetre or two of misalignment can cause uncomfortable or blurry vision.

Conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure, can affect the eyes so regular eye checks can also help flag broader health issues. The vast majority of eye conditions can be treated if caught early, highlighting the importance of regular preventative care.

James Andrew Armitage, Professor of Optometry and Course Director, Deakin University and Nick Hockley, Lecturer in Optometric Clinical Skills, Director Deakin Collaborative Eye Care Clinic, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: