PS, We Love You

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

PS, we love you. With good reason!

There are nearly 20,000 studies on PS listed on PubMed alone, and its established benefits include:

- significantly improving memory

- potential reversal (!) of neurodegeneration

- reduction of stress activation

- improvement in exercise capacity

- it even helps avoid rejection of medical implants

We’ll explore some of these studies and give an overview of how PS does what it does. Just like the (otherwise unrelated) l-theanine we talked about a couple of weeks ago, it does do a lot of things.

PS = Cow Brain?!

Let’s first address a concern. You may have heard something along the lines of “hey, isn’t PS made from cow brain, and isn’t that Very Bad™ for humans, mad cow disease and all?”. The short answer is:

Firstly: ingesting cow brain tissue is indeed generally considered Very Bad™ for humans, on account of the potential for transmission of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) resulting in its human equivalent, Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease (CJD), whose unpleasantries are beyond the scope of this newsletter.

Secondly (and more pleasantly): whilst PS can be derived from bovine brain tissue, most PS supplements these days derive from soy—or sometimes sunflower lecithin. Check labels if unsure.

Using PS to Improve Other Treatments

In the human body, the question of tolerance brings us a paradox (not the tolerance paradox, important as that may also be): we must build and maintain a strong immune system capable of quickly adapting to new things, and then when we need medicines (or even supplements), we need our body to not build tolerance of them, for them to continue having an effect.

So, we’re going to look at a very hot-off-the-press study (Feb 2023), that found PS to “mediate oral tolerance”, which means that it helps things (medications, supplements etc.) that we take orally and want to keep working, keep working.

In the scientists’ own words (we love scientists’ own words because they haven’t been distorted by the popular press)…

❝This immunotherapy has been shown to prevent/reduce immune response against life-saving protein-based therapies, food allergens, autoantigens, and the antigenic viral capsid peptide commonly used in gene therapy, suggesting a broad spectrum of potential clinical applications. Given the good safety profile of PS together with the ease of administration, oral tolerance achieved with PS-based nanoparticles has a very promising therapeutic impact.❞

Nguyen et al, Feb 2023

In other words, to parse those two very long sentences into two shorter bullet points:

- It allows a lot of important treatments to continue working—treatments that the body would otherwise counteract

- It is very safe—and won’t harm the normal function of your immune system at large

This is also very consistent with one of the benefits we mentioned up top—PS helps avoid rejection of implants, something that can be a huge difference to health-related quality of life (HRQoL), never mind sometimes life itself!

What is PS Anyways, and How Does It Work?

Phosphatidylserine is a phospholipid, a kind of lipid, found in cell membranes. More importantly:

It’s a signalling agent, mainly for apoptosis, which in lay terms means: it tells cells when it’s time to die.

Cellular death sounds like a bad thing, but prompt and efficient cellular apoptosis (death) and resultant prompt and efficient autophagy (recycling) reduce the risk of your body making mistakes when creating new cells from old cells.

Think about photocopying:

- Situation A: You have a document, and you want to copy it. If you copy it before it gets messed up, your copy will look almost, if not exactly, like the original. It’ll be super easy to read.

- Situation B: You have a document, and you want to copy it, but you delay doing so for so long that the original is all scuffed and creased and has a coffee stain on it. These unwanted changes will get copied onto the new document, and any copy made of that copy will keep the problems too. It gets worse and worse each time.

So, using this over-simplifier analogy, the speed of ‘copying’ is a major factor in cellular aging. The sooner cells are copied, before something gets damaged, the better the copy will be.

So you really, really want to have enough PS (our bodies make it too, by the way) to signal promptly to a cell when its time is up.

You do not want cells soldiering on until they’re the biological equivalent of that crumpled up, coffee-stained sheet of paper.

Little wonder, then, that PS’ most commonly-sought benefit when it comes to supplementation is to help avoid age-related neurodegeneration (most notably, memory loss)!

Keeping the cells young means keeping the brain young!

PS’s role as a signalling agent doesn’t end there—it also has a lot to say to a wide variety of the body’s immunological cells, helping them know what needs to happen to what. Some things should be immediately eaten and recycled; other things need more extreme measures applied to them first, and yet other things need to be ignored, and so forth.

You can read more about that in Elsevier’s publication if you’re curious 🙂

Wow, what a ride today’s newsletter has been! We started at paracetamoxyfrusebendroneomycin, and got down to the nitty gritty with a bunch of hopefully digestible science!

We love feedback, so please let us know if we’re striking the balance right, and/or if you’d like to see more or less of something—there’s a feedback widget at the bottom of this email!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What’s Your Ikigai?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ikigai: A Closer Look

We’ve mentioned ikigai from time to time, usually when discussing the characteristics associated with Blue Zone centenarians, for example as number 5 of…

It’s about finding one’s “purpose”. Not merely a function, but what actually drives you in life. And, if Japanese studies can be extrapolated to the rest of the world, it has a significant and large impact on mortality (other factors being controlled for); not having a sense of ikigai is associated with an approximately 47%* increase in 7-year mortality risk in the categories of cardiovascular disease and external cause mortality:

Sense of life worth living (ikigai) and mortality in Japan: Ohsaki Study

*we did a lot of averaging and fuzzy math to get this figure; the link will show you the full stats though!

In case that huge (n=43,391) study didn’t convince you, here’s another comparably-sized (n=43,117) one that found similarly, albeit framing the numbers the other way around, i.e. a comparable decrease in mortality risk for having a sense of ikigai:

This study was even longer (12 years rather than 7), so the fact that it found pretty much the same results the 7-year study we cited just before is quite compelling evidence. Again, multivariate hazard ratios were adjusted for age, BMI, drinking and smoking status, physical activity, sleep duration, education, occupation, marital status, perceived mental stress, and medical history—so all these things were effectively controlled for statistically.

Three kinds of ikigai

There are three principal kinds of ikigai:

- Social ikigai: for example, a caring role in the family or community, volunteer work, teaching

- Asocial ikigai: for example, a solitary practice of self-discipline, spirituality, or study without any particular intent to teach others

- Antisocial ikigai: for example, a strong desire to outlive an enemy, or to harm a person or group that one hates

You may be thinking: wait, aren’t those last things bad?

And… Maybe! But ikigai is not a matter of morality or even about “warm fuzzy feelings”. The fact is, having a sense of purpose increases longevity regardless of moral implications or niceness.

Nevertheless, for obvious reasons there is a lot more focus on the first two categories (social and asocial), and of those, especially the first category (social), because on a social level, “we all do well when we all do well”.

We exemplified them above, but they can be defined:

- Social: working for the betterment of society

- Asocial: working for the betterment of oneself

Of course, for many people, the same ikigai may cover both of those—often somebody who excels at something for its own sake and/but shares it with others to enrich their lives also, for example a teacher, an artist, a scientist, etc.

For it to cover both, however, requires that both parts of it are genuinely part of their feeling of ikigai, and not merely unintended consequences.

For example, a piano teacher who loves music in general and the piano in particular, and would gladly spend every waking moment studying/practising/performing, but hates having to teach it, but needs to pay the bills so teaches it anyway, cannot be said to be living any kind of social ikigai there, just asocial. And in fact, if teaching the piano is causing them to not have the time or energy to pursue it for its own sake, they might not even be living any ikigai at all.

One other thing to watch out for

There is one last stumbling block, which is that while we can find ikigai, we can also lose it! Examples of this may include:

- A professional whose job is their ikigai, until they face mandatory retirement or are otherwise unable to continue their work (perhaps due to disability, for example)

- A parent whose full-time-parent role is their ikigai, until their children leave for school, university, life in general

- A married person whose “devoted spouse” role is their ikigai, until their partner dies

For this reason, people of any age can have a “crisis of identity” that’s actually more of a “crisis of purpose”.

There are two ways of handling this:

- Have a back-up ikigai ready! For example, if your profession is your ikigai, maybe you have a hobby waiting in the wings, that you can smoothly jump ship to upon retirement.

- Embrace the fluidity of life! Sometimes, things don’t happen the way we expect. Sometimes life’s surprises can trip us up; sometimes they can leave us a sobbing wreck. But so long as life continues, there is an opportunity to pick ourselves up and decide where to go from that point. Note that this is not fatalism, by the way, it doesn’t have to be “this bad thing happened so that we could find this good thing, so really it was a good thing all along”. Rather, it can equally readily be “well, we absolutely did not want that bad thing to happen, but since it did, now we shall take it this way from here”.

For more on developing/maintaining psychological resilience in the face of life’s less welcome adversities, see:

Psychological Resilience Training

…and:

Putting The Abs Into Absurdity ← do not underestimate the power of this one

Take care!

Share This Post

-

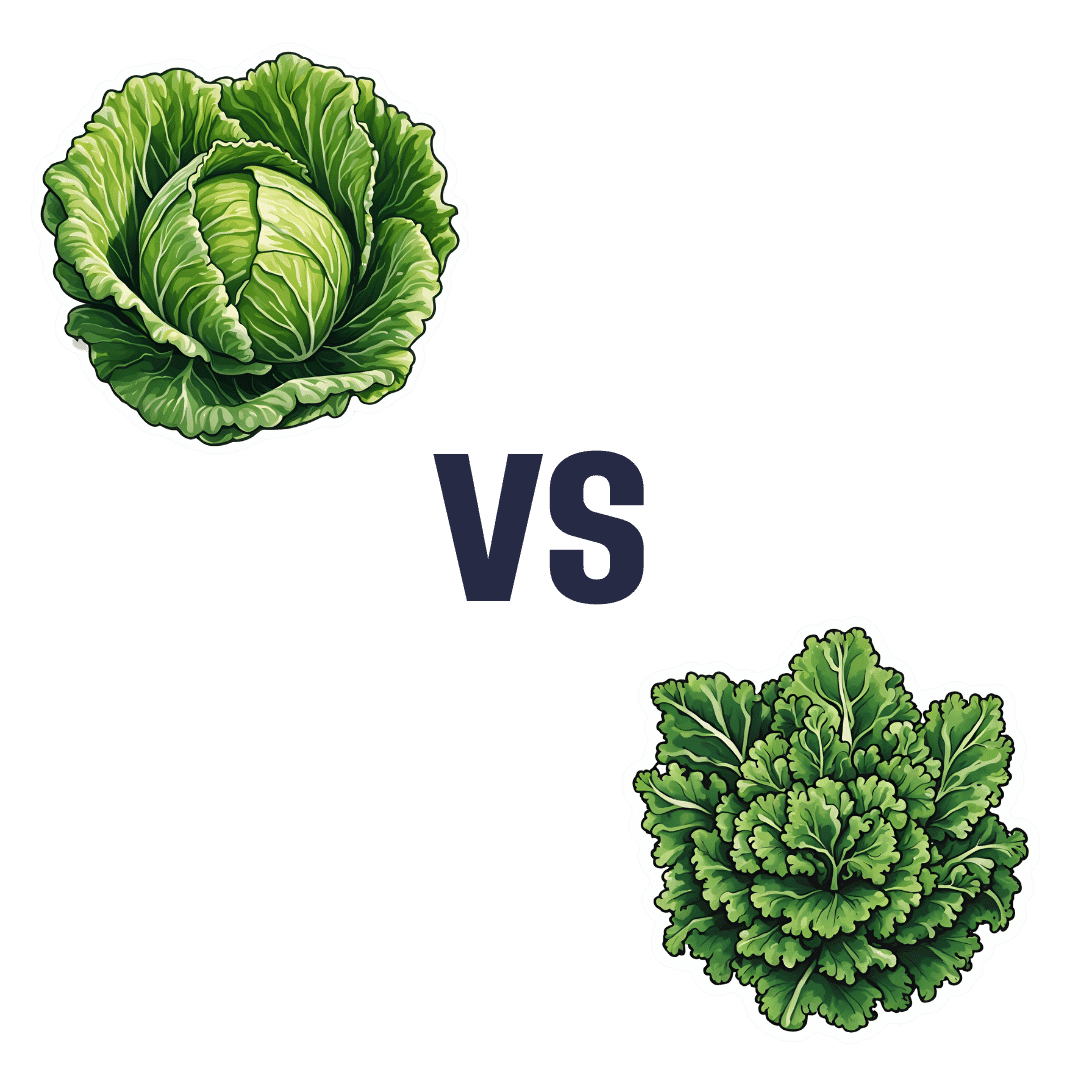

Cabbage vs Kale – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cabbage to kale, we picked the kale.

Why?

Here we go again, pitting Brassica oleracea vs Brassica oleracea. One species, many cultivars! Notwithstanding being the same species, there are important nutritional differences:

In terms of macros, kale has more protein, carbs, and fiber, and even has the lower glycemic index, not that cabbage is bad at all, of course. But nominally, kale gets the win on all counts in this category.

In the category of vitamins, cabbage has more of vitamins B5 and choline, while kale has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B7, B9, C, E, and K. An easy win for kale!

When it comes to minerals, it’s even more decisive: cabbage is not higher in any minerals, while kale has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc. Another clear win for kale.

Adding up the sections makes it very clear that kale wins the day, but we’d like to mention that cabbage was good in all of these metrics too; kale was just better!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

21 Most Beneficial Polyphenols & What Foods Have Them

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

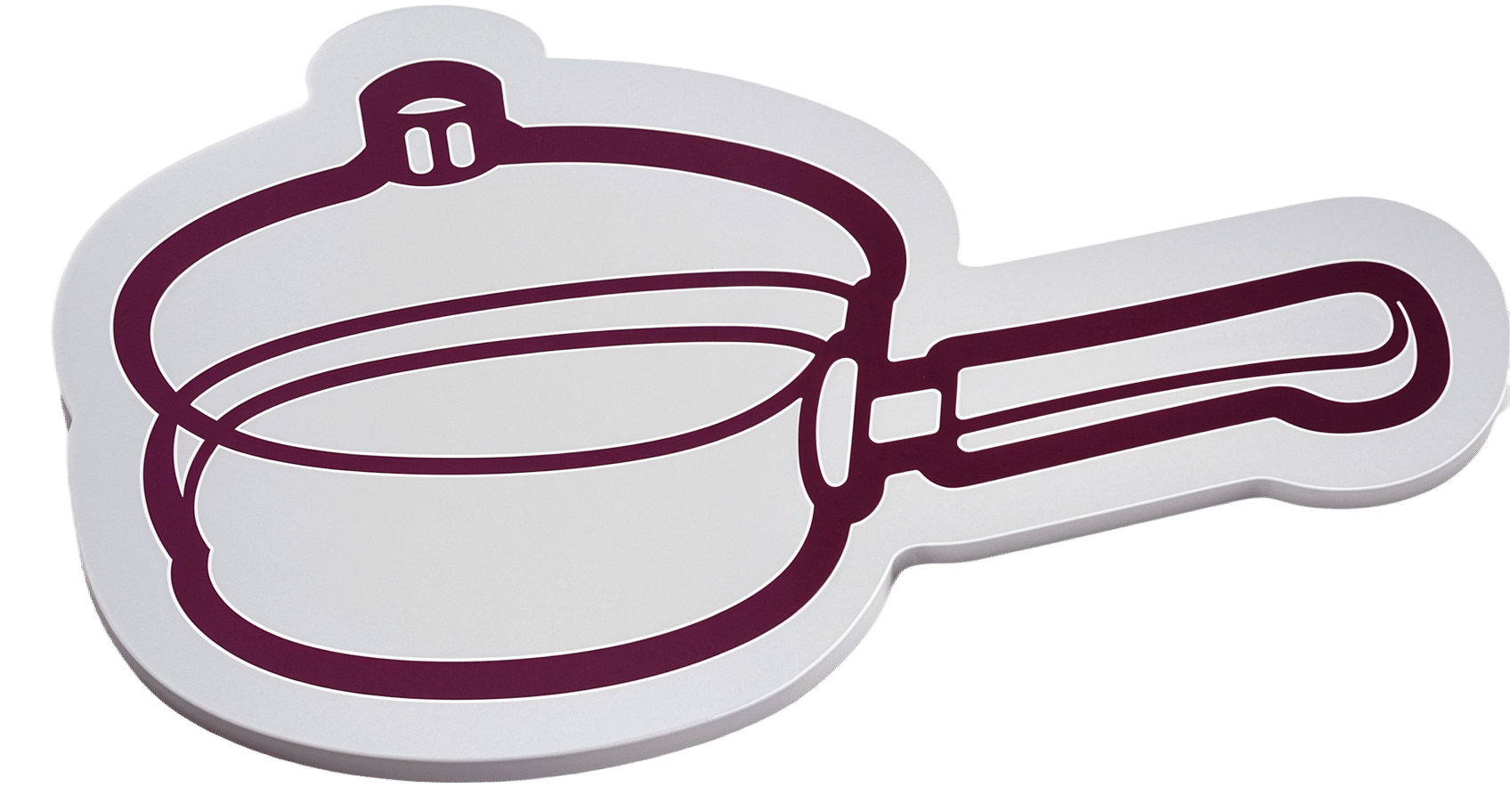

PFAS Exposure & Cancer: The Numbers Are High

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

PFAS & Cancer Risk: The Numbers Are High

Image Credits Mount Sinai This is Dr. Maaike van Gerwen. Is that an MD or a PhD, you wonder? It’s both.

She’s also Director of Research in the Department of Otolaryngology at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, Scientific Director of the Program of Personalized Management of Thyroid Disease, and Member of the Institute for Translational Epidemiology and the Transdisciplinary Center on Early Environmental Exposures.

What does she want us to know?

She’d love for us to know about her latest research published literally today, about the risks associated with PFAS, such as the kind widely found in non-stick cookware:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure and thyroid cancer risk

Dr. van Gerwen and her team tested this several ways, and the very short and simple version of the findings is that per doubling of exposure, there was a 56% increased rate of thyroid cancer diagnosis.

(The rate of exposure was not just guessed based on self-reports; it was measured directly from PFAS levels in the blood of participants)

- PFAS exposure can come from many sources, not just non-stick cookware, but that’s a “biggie” since it transfers directly into food that we consume.

- Same goes for widely-available microwaveable plastic food containers.

- Relatively less dangerous exposures include waterproofed clothing.

To keep it simple and look at the non-stick pans and microwavable plastic containers, doubling exposure might mean using such things every day vs every second day.

Practical take-away: PFAS may be impossible to avoid completely, but even just cutting down on the use of such products is already reducing your cancer risk.

Isn’t it too late, by this point in life? Aren’t they “forever chemicals”?

They’re not truly “forever”, but they do have long half-lives, yes.

See: Can we take the “forever” out of forever chemicals?

The half-lives of PFOS and PFOA in water are 41 years and 92 years, respectively.

In the body, however, because our body is constantly trying to repair itself and eliminate toxins, it’s more like 3–7 years.

That might seem like a long time, and perhaps it is, but the time will pass anyway, so might as well get started now, rather than in 3–7 years time!

Read more: National Academies Report Calls for Testing People With High Exposure to “Forever Chemicals”

What should we use instead?

In place of non-stick cookware, cast iron is fantastic. It’s not everyone’s preference, though, so you might also like to know that ceramic cookware is a fine option that’s functionally non-stick but without needing a non-stick coating. Check for PFAS-free status; they should advertise this.

In place of plastic microwaveable containers, Pyrex (or equivalent) glass dishes (you can get them with lids) are a top-tier option. Ceramic containers (without metallic bits!) are also safely microwaveable.

See also:

Here’s a List of Products with PFAS (& How to Avoid Them)

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Pain-Free Mindset – by Dr. Deepak Ravindran

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First: please ignore the terrible title. This is not the medical equivalent of “think and grow rich”. A better title would have been something like “The Pain-Free Plan”.

Attentive subscribers may notice that this author was our featured expert yesterday, so you can learn about his “seven steps” described in our article there, without us repeating that in our review here.

This book’s greatest strength is also potentially its greatest weakness, depending on the reader: it contains a lot of detailed medical information.

This is good or bad depending on whether you like lots of detailed medical information. Dr. Ravindran doesn’t assume prior knowledge, so everything is explained as we go. However, this means that after his well-referenced clinical explanations, high quality medical diagrams, etc, you may come out of this book feeling like you’ve just done a semester at medical school.

Knowledge is power, though, so understanding the underlying processes of pain and pain management really does help the reader become a more informed expert on your own pain—and options for reducing that pain.

Bottom line: this, disguised by its cover as a “think healing thoughts” book, is actually a science-centric, information-dense, well-sourced, comprehensive guide to pain management from one of the leading lights in the field.

Click here to check out The Pain-Free Mindset, and manage yours more comfortably!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mung Beans vs Black Gram – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing mung beans to black gram, we picked the black gram.

Why?

Both are great, and it was close!

In terms of macros, the main difference is that mung beans have slightly more fiber, while black gram has slightly more protein. So, it comes down to which we prioritize out of those two, and we’re going to call it fiber and thus hand the win in this category to mung beans—but it’s very close in either case.

In the category of vitamins, mung beans have more of vitamins B1, B6, and B9, while black gram has more of vitamins A, B2, B3, and B5. They’re equal on vitamins C, E, K, and choline. So, a marginal victory by the numbers for black gram here.

When it comes to minerals, mung beans have more copper and potassium, while black gram has more calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus. They’re equal on selenium and zinc. Another win for black gram.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for black gram, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why the WHO has recommended switching to a healthier salt alternative

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This week the World Health Organization (WHO) released new guidelines recommending people switch the regular salt they use at home for substitutes containing less sodium.

But what exactly are these salt alternatives? And why is the WHO recommending this? Let’s take a look.

goodbishop/Shutterstock A new solution to an old problem

Advice to eat less salt (sodium chloride) is not new. It has been part of international and Australian guidelines for decades. This is because evidence clearly shows the sodium in salt can harm our health when we eat too much of it.

Excess sodium increases the risk of high blood pressure, which affects millions of Australians (around one in three adults). High blood pressure (hypertension) in turn increases the risk of heart disease, stroke and kidney disease, among other conditions.

The WHO estimates 1.9 million deaths globally each year can be attributed to eating too much salt.

The WHO recommends consuming no more than 2g of sodium daily. However people eat on average more than double this, around 4.3g a day.

In 2013, WHO member states committed to reducing population sodium intake by 30% by 2025. But cutting salt intake has proved very hard. Most countries, including Australia, will not meet the WHO’s goal for reducing sodium intake by 2025. The WHO has since set the same target for 2030.

The difficulty is that eating less salt means accepting a less salty taste. It also requires changes to established ways of preparing food. This has proved too much to ask of people making food at home, and too much for the food industry.

There’s been little progress on efforts to cut sodium intake. snezhana k/Shutterstock Enter potassium-enriched salt

The main lower-sodium salt substitute is called potassium-enriched salt. This is salt where some of the sodium chloride has been replaced with potassium chloride.

Potassium is an essential mineral, playing a key role in all the body’s functions. The high potassium content of fresh fruit and vegetables is one of the main reasons they’re so good for you. While people are eating more sodium than they should, many don’t get enough potassium.

The WHO recommends a daily potassium intake of 3.5g, but on the whole, people in most countries consume significantly less than this.

Potassium-enriched salt benefits our health by cutting the amount of sodium we consume, and increasing the amount of potassium in our diets. Both help to lower blood pressure.

Switching regular salt for potassium-enriched salt has been shown to reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke and premature death in large trials around the world.

Modelling studies have projected that population-wide switches to potassium-enriched salt use would prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths from cardiovascular disease (such as heart attack and stroke) each year in China and India alone.

The key advantage of switching rather than cutting salt intake is that potassium-enriched salt can be used as a direct one-for-one swap for regular salt. It looks the same, works for seasoning and in recipes, and most people don’t notice any important difference in taste.

In the largest trial of potassium-enriched salt to date, more than 90% of people were still using the product after five years.

Excess sodium intake increases the risk of high blood pressure, which can cause a range of health problems. PeopleImages.com – Yuri A/Shutterstock Making the switch: some challenges

If fully implemented, this could be one of the most consequential pieces of advice the WHO has ever provided.

Millions of strokes and heart attacks could be prevented worldwide each year with a simple switch to the way we prepare foods. But there are some obstacles to overcome before we get to this point.

First, it will be important to balance the benefits and the risks. For example, people with advanced kidney disease don’t handle potassium well and so these products are not suitable for them. This is only a small proportion of the population, but we need to ensure potassium-enriched salt products are labelled with appropriate warnings.

A key challenge will be making potassium-enriched salt more affordable and accessible. Potassium chloride is more expensive to produce than sodium chloride, and at present, potassium-enriched salt is mostly sold as a niche health product at a premium price.

If you’re looking for it, salt substitutes may also be called low-sodium salt, potassium salt, heart salt, mineral salt, or sodium-reduced salt.

A review published in 2021 found low sodium salts were marketed in only 47 countries, mostly high-income ones. Prices ranged from the same as regular salt to almost 15 times higher.

An expanded supply chain that produces much more food-grade potassium chloride will be needed to enable wider availability of the product. And we’ll need to see potassium-enriched salt on the shelves next to regular salt so it’s easy for people to find.

In countries like Australia, about 80% of the salt we eat comes from processed foods. The WHO guideline falls short by not explicitly prioritising a switch for the salt used in food manufacturing.

Stakeholders working with government to encourage food industry uptake will be essential for maximising the health benefits.

Xiaoyue (Luna) Xu, Scientia Lecturer, School of Population Health, UNSW Sydney and Bruce Neal, Executive Director, George Institute Australia, George Institute for Global Health

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: