The 6 Pillars Of Nutritional Psychiatry

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

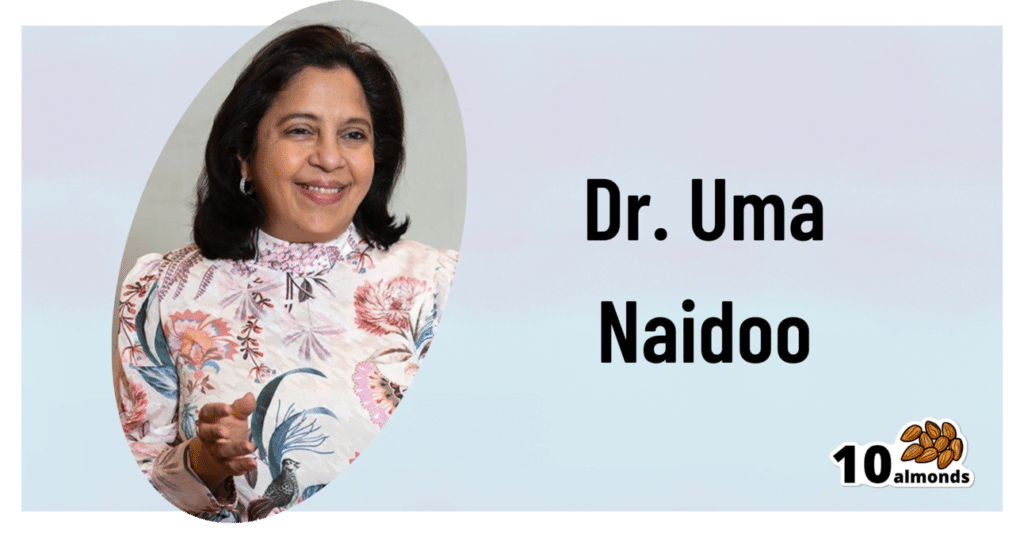

Dr. Naidoo’s To-Dos

This is Dr. Uma Naidoo. She’s a Harvard-trained psychiatrist, professional chef graduating with her culinary school’s most coveted award, and a trained nutritionist. Between those three qualifications, she knows her stuff when it comes to the niche that is nutritional psychiatry.

She’s also the Director of Nutritional and Lifestyle Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) & Director of Nutritional Psychiatry at MGH Academy while serving on the faculty at Harvard Medical School.

What is nutritional psychiatry?

Nutritional psychiatry is the study of how food influences our mood (in the short term) and our more generalized mental health (in the longer term).

We recently reviewed a book of hers on this topic:

This Is Your Brain On Food – by Dr. Uma Naidoo

The “Six Pillars” of nutritional psychiatry

Per Dr. Naidoo, these are…

Be Whole; Eat Whole

Here Dr. Naidoo recommends an “80/20 rule”, and a focus on fiber, to keep the gut (“the second brain”) healthy.

See also: The Brain-Gut Highway: A Two-Way Street

Eat The Rainbow

This one’s simple enough and speaks for itself. Very many brain-nutrients happen to be pigments, and “eating the rainbow” (plants, not Skittles!) is a way to ensure getting a lot of different kinds of brain-healthy flavonoids and other phytonutrients.

The Greener, The Better

As Dr. Naidoo writes:

❝Greens contain folate, an important vitamin that maintains the function of our neurotransmitters. Its consumption has been associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms and improved cognition.❞

Tap into Your Body Intelligence

This is about mindful eating, interoception, and keeping track of how we feel 30–60 minutes after eating different foods.

Basically, the same advice here as from: The Kitchen Doctor

(do check that out, as there’s more there than we have room to repeat here today!)

Consistency & Balance Are Key

Honestly, this one’s less a separate item and is more a reiteration of the 80/20 rule discussed in the first pillar, and an emphasis on creating sustainable change rather than loading up on brain-healthy superfoods for half a weekend and then going back to one’s previous dietary habits.

Avoid Anxiety-Triggering Foods

This is about avoiding sugar/HFCS, ultra-processed foods, and industrial seed oils such as canola and similar.

As for what to go for instead, she has a broad-palette menu of ingredients she recommends using as a base for one’s meals (remember she’s a celebrated chef as well as a psychiatrist and nutritionist), which you can check out here:

Dr. Naidoo’s “Food for Mood” project

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Before You Reach For That Tylenol…

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, on names: we’ve titled this with “Tylenol” because that’s a well-known brand name, but the drug name is paracetamol or acetaminophen:

- paracetamol is the drug name used by the World Health Organization, and thus also most countries.

- acetaminophen is the drug name used in Canada, Colombia, Iran, Japan, US, and Venezuela.

They are absolutely the same drug.

Firstly, obviously, do avoid overdose

The safe dosage described on the packet is generally accurate (usually around 4g/day, spaced out at 1g per 4 hours), and the dose required for toxicity is generally about 10g, or 200mg/kg body weight, whichever is lower. Since a single dose usually contains 2x 500mg = 1g, that makes overdose all too easy.

The amount required for toxicity can be misleading too, because that’s assuming…

- a healthy liver

- no other health problems

- no other medications that interact or add to the toxicity

- no medications that strain the liver (as with many pro-drugs, and drugs in general that are metabolized by the liver, which is lots).

Which is a lot of assumptions! Especially given that the liver can only process so much at once, meaning that if your liver has a lot of things to do, it can get a backlog, and you think “I’m not taking anything with this painkiller that I shouldn’t” but your liver is still metabolizing the last of last night’s glass of wine and one of your regular medications from this morning, because previously it was still metabolizing things from the day before yesterday, and so on.

See also: How To Regenerate Your Liver ← the liver is an incredible organ that does an amazing job, but it can’t do that if you don’t do this

Please don’t overdose deliberately either. Intentional overdoses make up a very large portion of acetaminophen overdoses (exact figures vary from year to year and place to place, but it’s always high), and what a lot of people doing that don’t realize is:

- it’s a very unpleasant way to die. You’ll take it, you might get some initial symptoms within the first hours or you might not, then you’ll probably feel better, and then the next day or so, you’ll enter the organs-shutting-down stage that usually will take most of a week to kill you slowly and painfully. Often your kidneys will go first but it’ll usually be liver necrosis that deals the final blow.

- it’s very difficult to treat. Stomach-pumping might work if you get it within 1 hour of overdose, and activated charcoal might help if you get it within 2 hours. Acetylcysteine may reduce the toxicity if you get it within the 8–48 hour window (depending on the speed of gastric emptying), but whether or not that will help depends on the severity of the overdose and other factors, so this is not something to bet on. After 48 hours, a liver transplant is the last resort, without which, mortality is around 95%.

Unfortunately, this means that a lot of people who do not intend to die horribly, and hoped to either die peacefully or else be saved, die horribly instead.

Ok, that was not a cheerful topic but it is important, before moving on, we’ll just put this here for anyone it may benefit:

How To Stay Alive (When You Really Don’t Want To) ← this is about suicidality, in yourself or others

Secondly, that dosage is for occasional use only

The problem often starts like this:

❝Due to its perceived safety, paracetamol has long been recommended as the first line drug treatment for osteoarthritis by many treatment guidelines, especially in older people who are at higher risk of drug-related complications❞

People with chronic pain, whether high or low on the pain level of that chronic pain, can very easily get into a habit of “I’ll just take this to take the edge off”, for example when getting up in the morning (often a trigger for pain starting) or going to bed at night (one needs to sleep and the pain is a barrier to that).

But… Those events, getting up and going to bed, it means that taking the drug also becomes part of one’s morning/evening routine—with many people even metering the doses out into pill organizers for the week, with this in mind.

A large (n=582,961) study looked at two groups of people, all aged 65+:

- 180,483 people who had been prescribed paracetamol repeatedly (≥2 prescriptions within six months)

- 402,478 people of the same age who had never been prescribed paracetamol repeatedly

The findings? Bearing in mind that “≥2 prescriptions within six months” is not something generally considered excessive…

❝Acetaminophen use was associated with an increased risk of peptic ulcer bleeding (aHR 1.24; 95% CI 1.16, 1.34), uncomplicated peptic-ulcers (aHR 1.20; 95% CI 1.10, 1.31), lower gastrointestinal-bleeding (aHR 1.36; 95% CI 1.29, 1.46), heart-failure (aHR 1.09; 95% CI 1.06, 1.13), hypertension (aHR 1.07; 95% CI 1.04, 1.11), and chronic kidney disease (aHR 1.19; 95% CI 1.13, 1.24).❞

The researchers concluded:

❝Despite its perceived safety, acetaminophen is associated with several serious complications. Given its minimal analgesic effectiveness, the use of acetaminophen as the first-line oral analgesic for long-term conditions in older people requires careful reconsideration.❞

You can see the study itself here: Incidence of side effects associated with acetaminophen in people aged 65 years or more: a prospective cohort study using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

What to use instead?

It’s been established that taking aspirin regularly isn’t great either:

See: Low-Dose Aspirin & Anemia and Aspirin, CVD Risk, & Potential Counter-Risks

And as for ibuprofen, we don’t have an article about that yet, but it’s gut-unhealthy (harms your microbiome), and besides, anything it can do, ginger can do as well or better (in head-to-head trials; we’re not speaking hyperbolically here):

Ginger Does A Lot More Than You Think ← in fact, it was even found as effective as the combination of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and caffeine

There are other options though, and as pain is complicated and there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, we’ve compiled the following:

- Dial Down Your Pain

- Stop Pain Spreading

- Managing Chronic Pain (Realistically!)

- The 7 Approaches To Pain Management

- Science-Based Alternative Pain Relief ← when painkillers aren’t helping, these things might

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Fennel vs Artichoke – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing fennel to artichoke, we picked the artichoke.

Why?

Both are great! But artichoke wins on nutritional density.

In terms of macros, artichoke has more protein and more fiber, for only slightly more carbs.

Vitamins are another win for artichoke, boasting more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, and choline. Meanwhile, fennel has more of vitamins A, E, and K, which is also very respectable but does allow artichoke a 6:3 lead.

In the category of minerals, artichoke has a lot more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus, while fennel has a little more calcium, potassium, and selenium.

One other relevant factor is that fennel is a moderate appetite suppressant, which may be good or bad depending on your food-related goals.

All in all though, we say the artichoke wins by virtue of its greater abundance of nutrients!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What Matters Most For Your Heart? ← appropriately enough, with fennel hearts and artichoke hearts!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Could Just Two Hours Sleep Per Day Be Enough?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Polyphasic Sleep… Super-Schedule Or An Idea Best Put To Rest?

What is it?

Let’s start by defining some terms:

- Monophasic sleep—sleeping in one “chunk” per day. For example, a good night’s “normal” sleep.

- Biphasic sleep—sleeping in two “chunks” per day. Typically, a shorter night’s sleep, with a nap usually around the middle of the day / early afternoon.

- Polyphasic sleep—sleeping in two or more “chunks per day”. Some people do this in order to have more hours awake per day, to do things. The idea is that sleeping this way is more efficient, and one can get enough rest in less time. The most popular schedules used are:

- The Überman schedule—six evenly-spaced 20-minute naps, one every four hours, throughout the 24-hour day. The name is a semi-anglicized version of the German word Übermensch, “Superman”.

- The Everyman schedule—a less extreme schedule, that has a three-hours “long sleep” during the night, and three evenly-spaced 20-minute naps during the day, for a total of 4 hours sleep.

There are other schedules, but we’ll focus on the most popular ones here.

Want to learn about the others? Visit: Polyphasic.Net (a website by and for polyphasic sleep enthusiasts)

Some people have pointed to evidence that suggests humans are naturally polyphasic sleepers, and that it is only modern lifestyles that have forced us to be (mostly) monophasic.

There is at least some evidence to suggest that when environmental light/dark conditions are changed (because of extreme seasonal variation at the poles, or, as in this case, because of artificial changes as part of a sleep science experiment), we adjust our sleeping patterns accordingly.

The counterpoint, of course, is that perhaps when at the mercy of long days/nights at the poles, or no air-conditioning to deal with the heat of the day in the tropics, that perhaps we were forced to be polyphasic, and now, with modern technology and greater control, we are free to be monophasic.

Either way, there are plenty of people who take up the practice of polyphasic sleep.

Ok, But… Why?

The main motivation for trying polyphasic sleep is simply to have more hours in the day! It’s exciting, the prospect of having 22 hours per day to be so productive and still have time over for leisure.

A secondary motivation for trying polyphasic sleep is that when the brain is sleep-deprived, it will prioritize REM sleep. Here’s where the Überman schedule becomes perhaps most interesting:

The six evenly-spaced naps of the Überman schedule are each 20 minutes long. This corresponds to the approximate length of a normal REM cycle.

Consequently, when your head hits the pillow, you’ll immediately begin dreaming, and at the end of your dream, the alarm will go off.

Waking up at the end of a dream, when one hasn’t yet entered a non-REM phase of sleep, will make you more likely to remember it. Similarly, going straight into REM sleep will make you more likely to be aware of it, thus, lucid dreaming.

Read: Sleep fragmentation and lucid dreaming (actually a very interesting and informative lucid dreaming study even if you don’t want to take up polyphasic sleep)

Six 20-minute lucid-dreaming sessions per day?! While awake for the other 22 hours?! That’s… 24 hours per day of wakefulness to use as you please! What sorcery is this?

Hence, it has quite an understandable appeal.

Next Question: Does it work?

Can we get by without the other (non-REM) kinds of sleep?

According to Überman cycle enthusiasts: Yes! The body and brain will adapt.

According to sleep scientists: No! The non-REM slow-wave phases of sleep are essential

Read: Adverse impact of polyphasic sleep patterns in humans—Report of the National Sleep Foundation sleep timing and variability consensus panel

(if you want to know just how bad it is… the top-listed “similar article” is entitled “Suicidal Ideation”)

But what about, for example, the Everman schedule? Three hours at night is enough for some non-REM sleep, right?

It is, and so it’s not as quickly deleterious to the health as the Überman schedule. But, unless you are blessed with rare genes that allow you to operate comfortably on 4 hours per day (you’ll know already if that describes you, without having to run any experiment), it’s still bad.

Adults typically need 7–9 hours of sleep per night, and if you don’t get it, you’ll accumulate a sleep debt. And, importantly:

When you accumulate sleep debt, you are borrowing time at a very high rate of interest!

And, at risk of laboring the metaphor, but this is important too:

Not only will you have to pay it back soon (with interest), you will be hounded by the debt collection agents—decreased cognitive ability and decreased physical ability—until you pay up.

In summary:

- Polyphasic sleep is really very tempting

- It will give you more hours per day (for a while)

- It will give the promised lucid dreaming benefits (which is great until you start micronapping between naps, this is effectively a mini psychotic break from reality lasting split seconds each—can be deadly if behind the wheel of a car, for instance!)

- It is unequivocally bad for the health and we do not recommend it

Bottom line:

Some of the claimed benefits are real, but are incredibly short-term, unsustainable, and come at a cost that’s far too high. We get why it’s tempting, but ultimately, it’s self-sabotage.

(Sadly! We really wanted it to work, too…)

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How Useful Are Our Dreams

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s In A Dream?

We were recently asked:

❝I have a question or a suggestion for coverage in your “Psychology Sunday”. Dreams: their relevance, meanings ( if any) interpretations? I just wondered what the modern psychological opinions are about dreams in general.❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

There are two main schools of thought, and one main effort to reconcile those two. The third one hasn’t quite caught on so far as to be considered a “school of thought” yet though.

The Top-Down Model (Psychoanalysts)

Psychoanalysts broadly follow the theories of Freud, or at least evolved from there. Freud was demonstrably wrong about very many things. Most of his theories have been debunked and ditched—hence the charitable “or at least evolved from there” phrasing when it comes to modern psychoanalytic schools of thought. Perhaps another day, we’ll go into all the ways Freud went wrong. However, for today, one thing he wasn’t bad at…

According to Freud, our dreams reveal our subconscious desires and fears, sometimes directly and sometimes dressed in metaphor.

Examples of literal representations might be:

- sex dreams (revealing our subconscious desires; perhaps consciously we had not thought about that person that way, or had not considered that sex act desirable)

- getting killed and dying (revealing our subconscious fear of death, not something most people give a lot of conscious thought to most of the time)

Examples of metaphorical representations might be:

- dreams of childhood (revealing our subconscious desires to feel safe and nurtured, or perhaps something else depending on the nature of the dream; maybe a return to innocence, or a clean slate)

- dreams of being pursued (revealing our subconscious fear of bad consequences of our actions/inactions, for example, responsibilities to which we have not attended, debts are a good example for many people; or social contact where the ball was left in our court and we dropped it, that kind of thing)

One can read all kinds of guides to dream symbology, and learn such arcane lore as “if you dream of your teeth crumbling, you have financial worries”, but the truth is that “this thing means that other thing” symbolic equations are not only highly personal, but also incredibly culture-bound.

For example:

- To one person, bees could be a symbol of feeling plagued by uncountable small threats; to another, they could be a symbol of abundance, or of teamwork

- One culture’s “crow as an omen of death” is another culture’s “crow as a symbol of wisdom”

- For that matter, in some cultures, white means purity; in others, it means death.

Even such classically Freudian things as dreaming of one’s mother and/or father (in whatever context) will be strongly informed by one’s own waking-world relationship (or lack thereof) with same. Even in Freud’s own psychoanalysis, the “mother” for the sake of such analysis was the person who nurtured, and the “father” was the person who drew the nurturer’s attention away, so they could be switched gender roles, or even different people entirely than one’s parents.

The only real way to know what, if anything, your dreams are trying to tell you, is to ask yourself. You can do that…

- by reflection and personal interrogation (see for example: The Easiest Way To Take Up Journaling)

- or by externalising parts of your subconscious (as in Internal Family Systems therapy)

- or by talking directly to your subconscious where it is, by means of lucid dreaming.

The idea with lucid dreaming is that since any dream character is a facet of your subconscious generated by your own mind, by talking to that character you can ask questions directly of your subconscious (the popular 2010 movie “Inception” was actually quite accurate in this regard, by the way).

To read more about how to do this kind of self-therapy through lucid dreaming, you might want to check out this book we reviewed previously; it is the go-to book of lucid dreaming enthusiasts, and will honestly give you everything you need in one go:

Lucid Dreaming: A Concise Guide to Awakening in Your Dreams and in Your Life – by Dr. Stephen LaBerge

The Bottom-Up Model (Neuroscientists)

This will take a lot less writing, because it’s practically a null hypothesis (i.e., the simplest default assumption before considering any additional evidence that might support or refute it; usually some variant of “nothing unusual going on here”).

The Bottom-Up model holds that our brains run regular maintenance cycles during REM sleep (a biological equivalent of defragging a computer), and the brain interprets these pieces of information flying by and, because of the mind’s tendency to look for patterns, fills in the rest (much like how modern generative AI can “expand” a source image to create more of the same and fill in the blanks), resulting in the often narratively wacky, but ultimately random, vivid hallucinations that we call dreams.

The Hybrid Model (per Cartwright, 2012)

This is really just one woman’s vision, but it’s an incredibly compelling one, that takes the Bottom-Up model and asks “what if we did all that bio-stuff, and then our subconscious mind influenced the interpretation of the random patterns, to create dreams that are subjectively meaningful, and thus do indeed represent our subconscious?

It’s best explained in her own words, though, so it’s time for another book recommendation (we’ve reviewed this one before, too):

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Oral retinoids can harm unborn babies. But many women taking them for acne may not be using contraception

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Oral retinoids are a type of medicine used to treat severe acne. They’re sold under the brand name Roaccutane, among others.

While oral retinoids are very effective, they can have harmful effects if taken during pregnancy. These medicines can cause miscarriages and major congenital abnormalities (harm to unborn babies) including in the brain, heart and face. At least 30% of children exposed to oral retinoids in pregnancy have severe congenital abnormalities.

Neurodevelopmental problems (in learning, reading, social skills, memory and attention) are also common.

Because of these risks, the Australasian College of Dermatologists advises oral retinoids should not be prescribed a month before or during pregnancy under any circumstances. Dermatologists are instructed to make sure a woman isn’t pregnant before starting this treatment, and discuss the risks with women of childbearing age.

But despite this, and warnings on the medicines’ packaging, pregnancies exposed to oral retinoids continue to be reported in Australia and around the world.

In a study published this month, we wanted to find out what proportion of Australian women of reproductive age were taking oral retinoids, and how many of these women were using contraception.

Our results suggest a high proportion of women are not using effective contraception while on these drugs, indicating Australia needs a strategy to reduce the risk oral retinoids pose to unborn babies.

Contraception options

Using birth control to avoid pregnancy during oral retinoid treatment is essential for women who are sexually active. Some contraception methods, however, are more reliable than others.

Long-acting-reversible contraceptives include intrauterine devices (IUDs) inserted into the womb (such as Mirena, Kyleena, or copper devices) and implants under the skin (such as Implanon). These “set and forget” methods are more than 99% effective.

Oral retinoids taken during pregnancy can cause complications in babies. Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock The effectiveness of oral contraceptive pills among “perfect” users (following the directions, with no missed or late pills) is similarly more than 99%. But in typical users, this can fall as low as 91%.

Condoms, when used as the sole method of contraception, have higher failure rates. Their effectiveness can be as low as 82% in typical users.

Oral retinoid use over time

For our study, we analysed medicine dispensing data among women aged 15–44 from Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) between 2013 and 2021.

We found the dispensing rate for oral retinoids doubled from one in every 71 women in 2013, to one in every 36 in 2021. The increase occurred across all ages but was most notable in young women.

Most women were not dispensed contraception at the same time they were using the oral retinoids. To be sure we weren’t missing any contraception that was supplied before the oral retinoids, we looked back in the data. For example, for an IUD that lasts five years, we looked back five years before the oral retinoid prescription.

Our analysis showed only one in four women provided oral retinoids were dispensed contraception simultaneously. This was even lower for 15- to 19-year-olds, where only about one in eight women who filled a prescription for oral retinoids were dispensed contraception.

A recent study found 43% of Australian year 10 and 69% of year 12 students are sexually active, so we can’t assume this younger age group largely had no need for contraception.

One limitation of our study is that it may underestimate contraception coverage, because not all contraceptive options are listed on the PBS. Those options not listed include male and female sterilisation, contraceptive rings, condoms, copper IUDs, and certain oral contraceptive pills.

But even if we presume some of the women in our study were using forms of contraception not listed on the PBS, we’re still left with a significant portion without evidence of contraception.

What are the solutions?

Other countries such as the United States and countries in Europe have pregnancy prevention programs for women taking oral retinoids. These programs include contraception requirements, risk acknowledgement forms and regular pregnancy tests. Despite these programs, unintended pregnancies among women using oral retinoids still occur in these countries.

But Australia has no official strategy for preventing pregnancies exposed to oral retinoids. Currently oral retinoids are prescribed by dermatologists, and most contraception is prescribed by GPs. Women therefore need to see two different doctors, which adds costs and burden.

Preventing pregnancy during oral retinoid treatment is essential. Krakenimages.com/Shutterstock Rather than a single fix, there are likely to be multiple solutions to this problem. Some dermatologists may not feel confident discussing sex or contraception with patients, so educating dermatologists about contraception is important. Education for women is equally important.

A clinical pathway is needed for reproductive-aged women to obtain both oral retinoids and effective contraception. Options may include GPs prescribing both medications, or dermatologists only prescribing oral retinoids when there’s a contraception plan already in place.

Some women may initially not be sexually active, but change their sexual behaviour while taking oral retinoids, so constant reminders and education are likely to be required.

Further, contraception access needs to be improved in Australia. Teenagers and young women in particular face barriers to accessing contraception, including costs, stigma and lack of knowledge.

Many doctors and women are doing the right thing. But every woman should have an effective contraception plan in place well before starting oral retinoids. Only if this happens can we reduce unintended pregnancies among women taking these medicines, and thereby reduce the risk of harm to unborn babies.

Dr Laura Gerhardy from NSW Health contributed to this article.

Antonia Shand, Research Fellow, Obstetrician, University of Sydney and Natasha Nassar, Professor of Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology and Chair in Translational Childhood Medicine, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Thinner Leaner Stronger – by Michael Matthews

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, the elephant in the training room: this book does assume that you want to be thinner, leaner, and stronger. This is the companion book, written for women, to “Bigger, Stronger, Leaner”, which was written for men. Statistically, these assumptions are reasonable, even if the generalizations are imperfect. Also, this reviewer has a gripe with anything selling “thinner”. Leaner was already sufficient, and “stronger” is the key element here, so “thinner” is just marketing, and marketing something that’s often not unhealthy, to sell a book that’s actually full of good advice for building a healthy body.

In other words: don’t judge a book by the cover, however eyeroll-worthy it may be.

The book is broadly aimed at middle-aged readers, but boasts equal worth for young and old alike. If there’s something Matthews knows how to do well in his writing, it’s hedging his bets.

As for what’s in the book: it’s diet and exercise advice, aimed at long-term implementation (i.e. not a crash course, but a lifestyle change), for maximum body composition change results while not doing anything silly (like many extreme short-term courses do) and not compromising other aspects of one’s health, while also not taking up an inordinate amount of time.

The dietary advice is sensible, broadly consistent with what we’d advise here, and/but if you want to maximise your body composition change results, you’re going to need a pocket calculator (or be better than this writer is at mental arithmetic).

The exercise advice is detailed, and a lot more specific than “lift things”; there are programs of specifically how many sets and reps and so forth, and when to increase the weights and when not to.

A strength of this book is that it explains why all those numbers are what they are, instead of just expecting the reader to take on faith that the best for a given exercise is (for example) 3 sets of 8–10 reps of 70–75% of one’s single-rep max for that exercise. Because without the explanation, those numbers would seem very arbitrary indeed, and that wouldn’t help anyone stick with the program. And so on, for any advice he gives.

The style is… A little flashy for this reader’s taste, a little salesy (and yes he does try to upsell to his personal coaching, but really, anything you need is in the book already), but when it comes down to it, all that gym-boy bravado doesn’t take away from the fact his advice is sound and helpful.

Bottom line: if you would like your body to be the three things mentioned in the title, this book can certainly help you get there.

Click here to check out Thinner Leaner Stronger, and become thinner, leaner, stronger!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: