Healthy Longevity As A Lifestyle Choice

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

7 Keys To Healthy Longevity

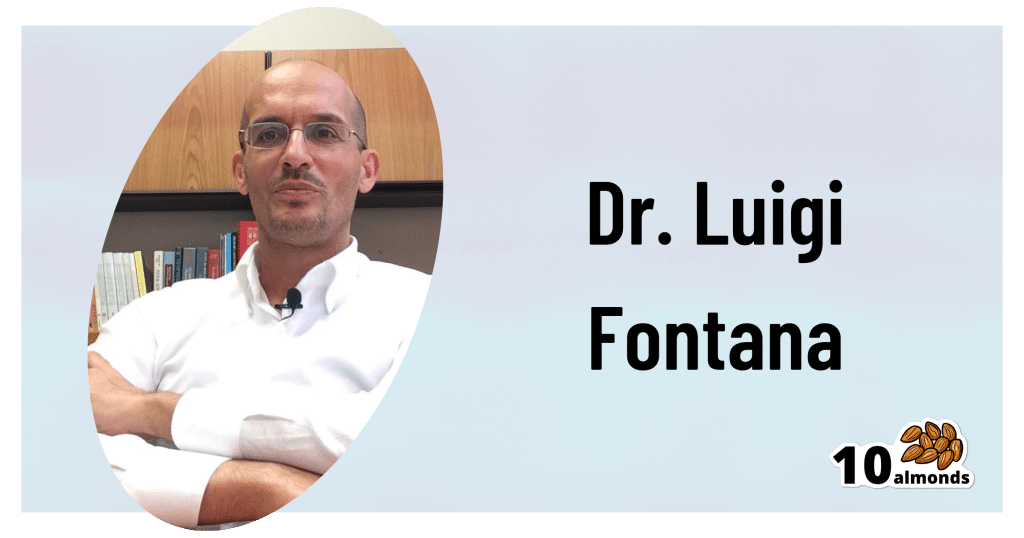

This is Dr. Luigi Fontana. He’s a research professor of Geriatrics & Nutritional Science, and co-director of the Longevity Research Program at Washington University in St. Louis.

What does he want us to know?

He has a many-fold approach to healthy longevity, most of which may not be news to you, but you might want to prioritize some things:

Consider caloric restriction with optimal nutrition (CRON)

This is about reducing the metabolic load on your body, which frees up bodily resources for keeping yourself young.

Keeping your body young and healthy is your body’s favorite thing to do, but it can’t do that if it never gets a chance because of all the urgent metabolic tasks you’re giving it.

If CRON isn’t your thing (isn’t practicable for you, causes undue suffering, etc) then intermittent fasting is a great CR mimetic, and he recommends that too. See also:

- Is Cutting Calories The Key To Healthy Long Life?

- Fasting Without Crashing? We Sort The Science From The Hype

Keep your waistline small

Whichever approach you prefer to use to look after your metabolic health, keeping your waistline down is much more important for health than BMI.

Specifically, he recommends keeping it:

- under 31.5” for women

- under 37” for men

The disparity here is because of hormonal differences that influence both metabolism and fat distribution.

Exercise as part of your lifestyle

For Dr. Fontana, he loves mountain-biking (this writer could never!) and weight-lifting (also not my thing). But what’s key is not the specifics, but what’s going on:

- Some kind of frequent movement

- Some kind of high-intensity interval training

- Some kind of resistance training

Frequent movement because our bodies are evolved to be moving more often than not:

The Doctor Who Wants Us To Exercise Less, & Move More

High-Intensity Interval Training because unlike most forms of exercise (which slow metabolism afterwards to compensate), it boosts metabolism for up to 2 hours after training:

How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body)

Resistance training because strength (of muscles and bones) matters too:

Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Writer’s examples:

So while I don’t care for mountain-biking or weight-lifting, what I do is:

1) movement: walk (briskly!) everywhere and also use a standing desk

2) HIIT: 2-minute bursts of hindu squats and/or exercise bike sprints

3) resistance: pilates and other calisthenics

Moderation is not key

Dr. Fontana advises that we do not smoke, and that we do not drink alcohol, for example. He also notes that just as the only healthy amount of alcohol is zero, less ultra-processed food is always better than more.

Maybe you don’t want to abstain completely, but mindful wilful consumption of something unhealthy is preferable to believing “moderate consumption is good for the health” and an unhealthy habit develops!

Greens and beans

Shocking absolutely nobody, Dr. Fontana advocates for (what has been the most evidence-based gold standard of healthy-aging diets for quite some years now) the Mediterranean diet.

See also: Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet ← this is about tweaking the Mediterranean diet per personal area of focus, e.g. anti-inflammatory bonus, best for gut, heart healthiest, and most neuroprotective.

Take it easy

Dr. Fontana advises us (again, with a wealth of evidence) Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and to get good sleep.

Not shocked?

To quote the good doctor,

❝There are no shortcuts. No magic pills or expensive procedures can replace the beneficial effects of a healthy diet, exercise, mindfulness, or a regenerating night’s sleep.❞

Always a good reminder!

Want to know more?

You might enjoy his book “The Path to Longevity: How to Reach 100 with the Health and Stamina of a 40-Year-Old”, which we reviewed previously

You might also like this video of his, about changing the conversation from “chronic disease” to “chronic health”:

Want to watch it, but not right now? Bookmark it for later

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

A Guide to Rational Living – by Drs. Albert Ellis and Robert Harper

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve talked before about the evidence-based benefits of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and this book is indeed about CBT. In fact, it’s in many ways the book that popularized Third Wave CBT—in other words, CBT in its modern form.

Dr. Ellis’s specific branch of CBT is Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, (REBT). What this means is using rationality to rewire emotions so that we’re not constantly sabotaging ourselves and our lives.

This is very much a “for the masses” book and doesn’t assume any prior knowledge of psychology, therapy, or psychotherapy. Or, for that matter, philosophy, since Stoic philosopher Epictetus had a lot to say that influenced Dr. Ellis’s work, too!

This book has also been described as “a self-help book for people who don’t like self-help books”… and certainly that Stoicism we mentioned does give the work a very different feel than a lot of books on the market.

The authors kick off with an initial chapter “How far can you go with self-therapy?”, and the answer is: quite far, even if it’s not a panacea. Everything has its limitations, and this book is no exception. On the other hand…

What the book does offer is a whole stack of tools, resources, and “How to…” chapters. In fact, there are so many “How to…” items in this book that, while it can be read cover-to-cover, it can also be used simply as a dip-in reference guide to refer to in times of need.

Bottom line: this book is highly recommendable to anyone and everyone, and if you don’t have it on your bookshelf, you should.

Click here to check out “A Guide To Rational Living” on Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

Crispy Tofu Pad Thai

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Easy to make, delicious to enjoy, and packed with phytonutrients, this dish is a great one to add to your repertoire:

You will need

- 10 oz ready-to-wok rice noodles, or 6 oz dry

- 5 oz silken tofu

- 5 oz firm or extra firm tofu, cut into small cubes

- 1 oz arrowroot (or cornstarch if you don’t have arrowroot)

- 4 scallions, sliced

- ¼ bulb garlic, finely chopped

- 1″ piece fresh ginger, grated

- 1 red chili, chopped (multiply per your heat preferences)

- 1 red bell pepper, deseeded and thinly sliced

- 4 oz bok choi, thinly sliced

- 4 oz mung bean sprouts

- 1 tbsp tamari (or other, but tamari is traditional) soy sauce

- 1 tbsp sweet chili sauce

- Juice of ½ lime

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Avocado oil, or your preferred oil for stir-frying

- To serve: lime wedges

- Optional garnish: crushed roasted peanuts (if allergic, substitute sesame seeds; peanuts are simply traditional, that’s all)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Scramble the silken tofu. For guidance and also additional seasoning pointers, see our Tasty Tofu Scramble recipe, but omit the thyme.

2) Cook the noodles if necessary (i.e. if they are the dry type and need boiling, as opposed to “ready-to-wok” noodles that don’t), drain, and set aside.

4) Prepare the tofu cubes: if the tofu cubes are dry to the touch, toss them gently in a little oil to coat. If they’re wet to the touch, no need. Dust the tofu cubes with the arrowroot and MSG/salt; you can do this in a bowl, tossing gently to distribute the coating evenly.

4) Heat some oil in a wok over a high heat, and fry the tofu on each side until golden and crispy all over, and set aside.

5) Stir-fry the scallions, garlic, ginger, chili, and bell pepper for about 2 minutes.

6) Add the bean sprouts and bok choi, and keep stir-frying for another 2 minutes.

7) Add everything that’s not already in the pan except the lime wedges and peanuts (i.e., add the things you set aside, plus the remaining as-yet-untouched ingredients) and stir-fry for a further 2 minutes.

8) Serve hot, garnished with the crushed peanuts if using, and with the lime wedges on the side:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Sprout Your Seeds, Grains, Beans, Etc

- Which Bell Peppers To Pick? A Spectrum Of Specialties

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Grains: Bread Of Life, Or Cereal Killer?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Going Against The Grain?

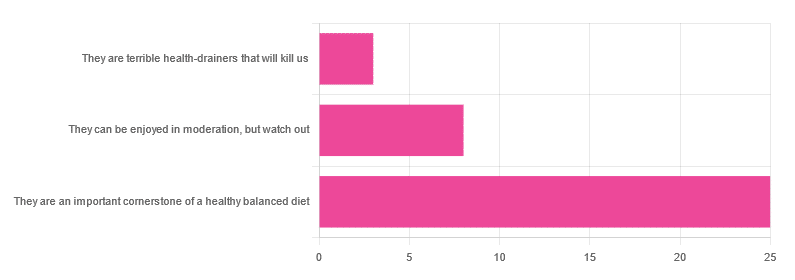

In Wednesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your health-related opinion of grains (aside from any gluten-specific concerns), and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 69% said “They are an important cornerstone of a healthy balanced diet”

- About 22% said “They can be enjoyed in moderation, but watch out”

- About 8% said “They are terrible health-drainers that will kill us”

So, what does the science say?

They are terrible health-drainers that will kill us: True or False?

True or False depending on the manner of their consumption!

There is a big difference between the average pizza base and a bowl of oats, for instance. Or rather, there are a lot of differences, but what’s most critical here?

The key is: refined and ultraprocessed grains are so inferior to whole grains as to be actively negative for health in most cases for most people most of the time.

But! It’s not because processing is ontologically evil (in reality: some processed foods are healthy, and some unprocessed foods are poisonous). although it is a very good general rule of thumb.

So, we need to understand the “why” behind the “key” that we just gave above, and that’s mostly about the resultant glycemic index and associated metrics (glycemic load, insulin index, etc).

In the case of refined and ultraprocessed grains, our body gains sugar faster than it can process it, and stores it wherever and however it can, like someone who has just realised that they will be entertaining a houseguest in 10 minutes and must tidy up super-rapidly by hiding things wherever they’ll fit.

And when the body tries to do this with sugar from refined grains, the result is very bad for multiple organs (most notably the liver, but the pancreas takes quite a hit too) which in turn causes damage elsewhere in the body, not to mention that we now have urgently-produced fat stored in unfortunate places like our liver and abdominal cavity when it should have gone to subcutaneous fat stores instead.

In contrast, whole grains come with fiber that slows down the absorption of the sugars, such that the body can deal with them in an ideal fashion, which usually means:

- using them immediately, or

- storing them as muscle glycogen, or

- storing them as subcutaneous fat

👆 that’s an oversimplification, but we only have so much room here.

For more on this, see:

Glycemic Index vs Glycemic Load vs Insulin Index

And for why this matters, see:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

And for fixing it, see:

They can be enjoyed in moderation, but watch out: True or False?

Technically True but functionally False:

- Technically true: “in moderation” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. One person’s “moderation” may be another person’s “abstemiousness” or “gluttony”.

- Functionally false: while of course extreme consumption of pretty much anything is going to be bad, unless you are Cereals Georg eating 10,000 cereals each day and being a statistical outlier, the issue is not the quantity so much as the quality.

Quality, we discussed above—and that is, as we say, paramount. As for quantity however, you might want to know a baseline for “getting enough”, so…

They are an important cornerstone of a healthy balanced diet: True or False?

True! This one’s quite straightforward.

3 servings (each being 90g, or about ½ cup) of whole grains per day is associated with a 22% reduction in risk of heart disease, 5% reduction in all-cause mortality, and a lot of benefits across a lot of disease risks:

❝This meta-analysis provides further evidence that whole grain intake is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and total cancer, and mortality from all causes, respiratory diseases, infectious diseases, diabetes, and all non-cardiovascular, non-cancer causes.

These findings support dietary guidelines that recommend increased intake of whole grain to reduce the risk of chronic diseases and premature mortality.❞

~ Dr. Dagfinn Aune et al.

We’d like to give a lot more sources for the same findings, as well as papers for all the individual claims, but frankly, there are so many that there isn’t room. Suffice it to say, this is neither controversial nor uncertain; these benefits are well-established.

Here’s a very informative pop-science article, that also covers some of the things we discussed earlier (it shows what happens during refinement of grains) before getting on to recommendations and more citations for claims than we can fit here:

Harvard School Of Public Health | Whole Grains

“That’s all great, but what if I am concerned about gluten?”

There certainly are reasons you might be, be it because of a sensitivity, allergy, or just because perhaps you’d like to know more.

Let’s first mention: not all grains contain gluten, so it’s perfectly possible to enjoy naturally gluten-free grains (such as oats and rice) as well as gluten-free pseudocereals, which are not actually grains but do the same job in culinary and nutritional terms (such as quinoa and buckwheat, despite the latter’s name).

Finally, if you’d like to know more about gluten’s health considerations, then check out our previous mythbusting special:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

First things first… How much fiber should we be eating?

- The World Health Organization recommends we each get at least 25g of fiber per day:

- A more recent meta-review of studies, involving thousands of people and decades of time, suggests 25–29g is ideal:

- The British Nutritional Foundation gives 30g as the figure:

- The US National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine recommends 21g–38g per day, depending on age and sex:

- A large study last year gave 30–40g as the figure:

*This one is also a great read to understand more about the “why” of fiber

Meanwhile, the average American gets 16g of fiber per day.

So, how to get more fiber, without piling on too many carbs?

Foods that contain fiber generally contain carbs (there’s a limit to how much celery most people want to eat), so there are two key ideas here:

- Getting a good carb:fiber ratio

- Making substitutions that boost fiber without overdoing (or in some case, even changing) carbs

Meat → Lentils

Well-seasoned lentils can be used to replaced ground beef or similar. A cup of boiled lentils contains 18g of fiber, so you’re already outdoing the average American’s daily total.

Meat → Beans

Black beans are a top-tier option here (15g per cup, cooked weight), but many kinds of beans are great.

Chicken/Fish → Chickpeas

Yes, chicken/fish is already meat, but we’re making a case for chickpeas here. Cooked and seasoned appropriately, they do the job, and pack in 12g of fiber per cup. Also… Hummus!

Bonus: Hummus, eaten with celery sticks.

White pasta/bread → Wholewheat pasta/bread

This is one where “moderation is key”, but if you’re going to eat pasta/bread, then wholewheat is the way to go. Fiber amounts vary, so read labels, but it will always have far more than white.

Processed salty snacks → Almonds and other nuts

Nuts in general are great, but almonds are top-tier for fiber, amongst other things. A 40g handful of almonds contains about 10g of fiber.

Starchy vegetables → Non-starchy vegetables

Potatoes, parsnips, and their friends have their place. But they cannot compete with broccoli, peas, cabbage, and other non-starchy vegetables for fiber content.

Bonus: if you’re going to have starchy vegetables though, leave the skins on!

Fruit juice → Fruit

Fruit juice has had most, if not all, of its fiber removed. Eat an actual juicy fruit, instead. Apples and bananas are great options; berries such as blackberries and raspberries are even better (at around 8g per cup, compared to the 5g or so depending on the size of an apple/banana)

Processed cereals → Oats

5g fiber per cup. Enough said.

Summary

Far from being a Herculean task, getting >30g of fiber per day can be easily accomplished by a lentil ragù with wholewheat pasta.

If your breakfast is overnight oats with fruit and some chopped almonds, you can make it to >20g already by the time you’ve finished your first meal of the day.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Healthy Cook’s Anti-Inflammatory Diet & Cookbook – by Dr. Albert Orbinati

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Chronic inflammation is a root cause of very many illnesses, and exacerbates almost all the ones it doesn’t cause. So, reducing inflammation is a very good way to stay well in general, reducing one’s risk factors for very many other diseases.

Dr. Orbinati starts by giving advice for adjusting to an anti-inflammatory diet, including advice on trying an elimination diet, if you suspect an undiagnosed allergy/intolerance.

Thereafter, he gives guidance on pantry-stocking—not just what anti-inflammatory foods to include and what inflammatory foods to skip, but also, what food and nutrient pairings are particularly beneficial, like how black pepper and turmeric are both anti-inflammatory by themselves, but the former greatly increases the bioavailability of the latter if consumed together.

The rest of the book—aside from assorted appendices, such as 8 pages of scientific references—is given over to the recipes.

The recipes themselves are, obviously, anti-inflammatory in focus. As one might expect, therefore, most are vegetarian and many are vegan, but we do find many recipes with chicken and fish as well; there’s also some use of eggs and fermented dairy in some of the recipes too.

The book certainly does deliver on its promise of flavorful healthy food; that’s what happens when one includes a lot of herbs and spices in one’s cooking, as well as the fact that many other polyphenol-rich foods are, by nature, tasty in and of themselves.

Bottom line: if you’d like to expand your anti-inflammatory culinary repertoire, this book is a top-tier choice for that.

Click here to check out Healthy Cook’s Anti-Inflammatory Diet & Cookbook, and spice up your kitchen!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Anti-Cholesterol Cardamom & Pistachio Porridge

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This tasty breakfast’s beta-glucan content binds to cholesterol and carries it out of the body; there are lots of other nutritional benefits too!

You will need

- 1 cup coconut milk

- ⅓ cup oats

- 4 tbsp crushed pistachios

- 6 cardamom pods, crushed

- 1 tsp rose water or 4 drops edible rose essential oil

- Optional sweetener: drizzle of honey or maple syrup

- Optional garnishes: rose petals, chopped nuts, dried fruit

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat the coconut milk, adding the oats and crushed cardamom pods. Simmer for 5–10 minutes depending on how cooked you want the oats to be.

2) Stir in the crushed pistachio nuts, as well as the rose water.

3) Serve in a bowl, adding any optional toppings:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- The Best Kind Of Fiber For Overall Health? ← it’s beta-glucan, which is fund abundantly in oats

- Pistachios vs Pecans – Which is Healthier? ← have a guess

- Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy? ← coconut can!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: