I’m feeling run down. Why am I more likely to get sick? And how can I boost my immune system?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It has been a long winter, filled with many viruses and cost-of-living pressures, on top of the usual mix of work, study, life admin and caring responsibilities.

Stress is an inevitable part of life. In short bursts, our stress response has evolved as a survival mechanism to help us be more alert in fight or flight situations.

But when stress is chronic, it weakens the immune system and makes us more vulnerable to illnesses such as the common cold, flu and COVID.

Stress makes it harder to fight off viruses

When the immune system starts to break down, a virus that would normally have been under control starts to flourish.

Once you begin to feel sick, the stress response rises, making it harder for the immune system to fight off the disease. You may be sick more often and for longer periods of time, without enough immune cells primed and ready to fight.

In the 1990s, American psychology professor Sheldon Cohen and his colleagues conducted a number of studies where healthy people were exposed to an upper respiratory infection, through drops of virus placed directly into their nose.

These participants were then quarantined in a hotel and monitored closely to determine who became ill.

One of the most important factors predicting who got sick was prolonged psychological stress.

Cortisol suppresses immunity

“Short-term stress” is stress that lasts for a period of minutes to hours, while “chronic stress” persists for several hours per day for weeks or months.

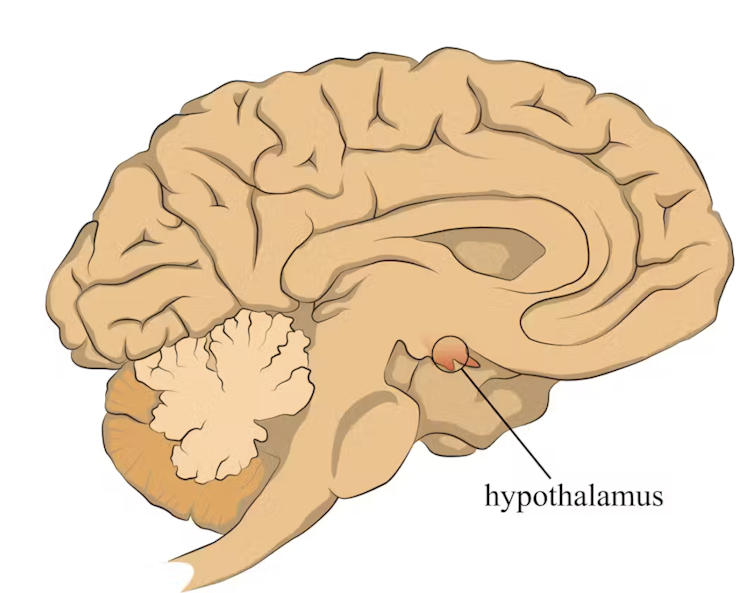

When faced with a perceived threat, psychological or physical, the hypothalamus region of the brain sets off an alarm system. This signals the release of a surge of hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol.

In a typical stress response, cortisol levels quickly increase when stress occurs, and then rapidly drop back to normal once the stress has subsided. In the short term, cortisol suppresses inflammation, to ensure the body has enough energy available to respond to an immediate threat.

But in the longer term, chronic stress can be harmful. A Harvard University study from 2022 showed that people suffering from psychological distress in the lead up to their COVID infection had a greater chance of experiencing long COVID. They classified this distress as depression, probable anxiety, perceived stress, worry about COVID and loneliness.

Those suffering distress had close to a 50% greater risk of long COVID compared to other participants. Cortisol has been shown to be high in the most severe cases of COVID.

Stress causes inflammation

Inflammation is a short-term reaction to an injury or infection. It is responsible for trafficking immune cells in your body so the right cells are present in the right locations at the right times and at the right levels.

The immune cells also store a memory of that threat to respond faster and more effectively the next time.

Initially, circulating immune cells detect and flock to the site of infection. Messenger proteins, known as pro-inflammatory cytokines, are released by immune cells, to signal the danger and recruit help, and our immune system responds to neutralise the threat.

During this response to the infection, if the immune system produces too much of these inflammatory chemicals, it can trigger symptoms such as nasal congestion and runny nose.

What about chronic stress?

Chronic stress causes persistently high cortisol secretion, which remains high even in the absence of an immediate stressor.

The immune system becomes desensitised and unresponsive to this cortisol suppression, increasing low-grade “silent” inflammation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (the messenger proteins).

Immune cells become exhausted and start to malfunction. The body loses the ability to turn down the inflammatory response.

Over time, the immune system changes the way it responds by reprogramming to a “low surveillance mode”. The immune system misses early opportunities to destroy threats, and the process of recovery can take longer.

So how can you manage your stress?

We can actively strengthen our immunity and natural defences by managing our stress levels. Rather than letting stress build up, try to address it early and frequently by:

1) Getting enough sleep

Getting enough sleep reduces cortisol levels and inflammation. During sleep, the immune system releases cytokines, which help fight infections and inflammation.

2) Taking regular exercise

Exercising helps the lymphatic system (which balances bodily fluids as part of the immune system) circulate and allows immune cells to monitor for threats, while sweating flushes toxins. Physical activity also lowers stress hormone levels through the release of positive brain signals.

3) Eating a healthy diet

Ensuring your diet contains enough nutrients – such as the B vitamins, and the full breadth of minerals like magnesium, iron and zinc – during times of stress has a positive impact on overall stress levels. Staying hydrated helps the body to flush out toxins.

4) Socialising and practising meditation or mindfulness

These activities increase endorphins and serotonin, which improve mood and have anti-inflammatory effects. Breathing exercises and meditation stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, which calms down our stress responses so we can “reset” and reduce cortisol levels.

Sathana Dushyanthen, Academic Specialist & Lecturer in Cancer Sciences & Digital Health| Superstar of STEM| Science Communicator, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Do You Know These 10 Common Ovarian Cancer Symptoms?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s better to know in advance:

Things you may need to know

The symptoms listed in the video are:

- Abdominal bloating: persistent bloating due to fluid buildup, often mistaken for overeating or weight gain.

- Pelvic or abdominal pain: continuous pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis, unrelated to menstruation.

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly: loss of appetite or feeling full after eating only a small amount.

- Urgent or frequent urination: increased need to urinate due to tumor pressure on the bladder.

- Unexplained weight loss: sudden weight loss without changes in diet or exercise (this goes for cancer in general, of course).

- Fatigue: extreme tiredness that doesn’t improve with rest, possibly linked to anemia.

- Back pain: persistent lower back pain due to tumor pressure or fluid buildup.

- Changes in bowel habits: unexplained constipation, diarrhea, or a feeling of incomplete bowel movements.

- Menstrual changes: irregular, heavier, lighter, or missed periods in premenopausal women.

- Pain during intercourse: discomfort or deep pelvic pain during or after vaginal sex—often overlooked!

Of course, some of those things can be caused by many things, but it’s worth getting it checked out, especially if you have a cluster of them together. Even if it’s not ovarian cancer (and hopefully it won’t be), having multiple things from this list certainly means that “something wrong is not right” in any case.

For those who remember better from videos than what you read, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care

Share This Post

-

Glycemic Index vs Glycemic Load vs Insulin Index

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How To Actually Use Those Indices

Carbohydrates are essential for our life, and/but often bring about our early demise. It would be a very conveniently simple world if it were simply a matter of “enjoy in moderation”, but the truth is, it’s not that simple.

To take an extreme example, for the sake of clearest illustration: The person who eats an 80% whole fruit diet (and makes up the necessary protein and fats etc in the other 20%) will probably be healthier than the person who eats a “standard American diet”, despite not practising moderation in their fruit-eating activities. The “standard American diet” has many faults, and one of those faults is how it promotes sporadic insulin spikes leading to metabolic disease.

If your breakfast is a glass of orange juice, this is a supremely “moderate” consumption, but an insulin spike is an insulin spike.

Quick sidenote: if you’re wondering why eating immoderate amounts of fruit is unlikely to cause such spikes, but a single glass of orange juice is, check out:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Glycemic Index

The first tool in our toolbox here is glycemic index, or GI.

GI measures how much a carb-containing food raises blood glucose levels, also called blood sugar levels, but it’s just glucose that’s actually measured, bearing in mind that more complex carbs will generally get broken down to glucose.

Pure glucose has a GI of 100, and other foods are ranked from 0 to 100 based on how they compare.

Sometimes, what we do to foods changes its GI.

- Some is because it changed form, like the above example of whole fruit (low GI) vs fruit juice (high GI).

- Some is because of more “industrial” refinement processes, such as whole grain wheat (medium GI) vs white flour and white flour products (high GI)

- Some is because of other changes, like starches that were allowed to cool before being reheated (or eaten cold).

Broadly speaking, a daily average GI of 45 is considered great.

But that’s not the whole story…

Glycemic Load

Glycemic Load, or GL, takes the GI and says “ok, but how much of it was there?”, because this is often relevant information.

Refined sugar may have a high GI, but half a teaspoon of sugar in your coffee isn’t going to move your blood sugar levels as much as a glass of Coke, say—the latter simply has more sugar in, and just the same zero fiber.

GL is calculated by (grams of carbs / 100) x GI, by the way.

But it still misses some important things, so now let’s look at…

Insulin Index

Insulin Index, which does not get an abbreviation (probably because of the potentially confusing appearance of “II”), measures the rise in insulin levels, regardless of glucose levels.

This is important, because a lot of insulin response is independent of blood glucose:

- Some is because of other sugars, some some is in response to fats, and yes, even proteins.

- Some is a function of metabolic base rate.

- Some is a stress response.

- Some remains a mystery!

Another reason it’s important is that insulin drives weight gain and metabolic disorders far more than glucose.

Note: the indices of foods are calculated based on average non-diabetic response. If for example you have Type 1 Diabetes, then when you take a certain food, your rise in insulin is going to be whatever insulin you then take, because your body’s insulin response is disrupted by being too busy fighting a civil war in your pancreas.

If your diabetes is type 2, or you are prediabetic, then a lot of different things could happen depending on the stage and state of your diabetes, but the insulin index is still a very good thing to be aware of, because you want to resensitize your body to insulin, which means (barring any urgent actions for immediate management of hyper- or hypoglycemia, obviously) you want to eat foods with a low insulin index where possible.

Great! What foods have a low insulin index?

Many factors affect insulin index, but to speak in general terms:

- Whole plant foods are usually top-tier options

- Lean and/or white meats generally have lower insulin index than red and/or fatty ones

- Unprocessed is generally lower than processed

- The more solid a food is, generally the lower its insulin index compared to a less solid version of the same food (e.g. baked potatoes vs mashed potatoes; cheese vs milk, etc)

But do remember the non-food factors too! This means where possible:

- reducing/managing stress

- getting frequent exercise

- getting good sleep

- practising intermittent fasting

See for example (we promise you it’s relevant):

Fix Chronic Fatigue & Regain Your Energy, By Science

…as are (especially recommendable!) the two links we drop at the bottom of that page; do check them out if you can

Take care!

Share This Post

-

How Your Exercise Today Gives A Brain Boost Tomorrow

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Regular 10almonds readers may remember we not long back wrote about a study that showed how daily activity levels, in aggregate, make a difference to brain health over the course of 1–2 weeks (in fact, it was a 9-day study):

Daily Activity Levels & The Measurable Difference They Make To Brain Health

Today, we’re going to talk about a new (published today, at time of writing) study that shows the associations between daily exercise levels (amongst other things) and how well people performed in cognitive tests the next day.

By this we mean: they recorded exercise vs sedentary behavior vs sleep on a daily basis (using wearable tech to track it), and tested them daily with cognitive tests, and looked at how the previous day’s activities (or lack thereof) impacted the next day’s test results.

Notably, the sample was of older adults (aged 50–83). The sample size wasn’t huge but was statistically significant (n=76) and the researchers are of course calling for more studies to be done with more people.

What they found

To put their findings into few words:

- Consistent light exercise boosts general cognitive performance not just for hours (which was already known) but through the next day.

- More moderate or vigorous activity than usual in particular led to better working memory and episodic memory the next day.

- More sleep (especially slow-wave deep sleep) improved episodic memory and psychomotor speed.

- Sedentary behavior was associated with poorer working memory.

Let’s define some terms:

- general cognitive performance = average of scores across the different tests

- working memory = very short term memory, such as remembering what you came into this room for, or (as an example of a test format) being able to take down a multi-digit number in one go without it being broken down (and then, testing with longer lengths of number until failure)

- episodic memory = memory of events in a narrative context, where and when they happened, etc

- psychomotor speed = the speed of connection between perception and reaction in quick-response tests

These are, of course, all useful things to have, which means the general advice here is to:

- move more, generally

- exercise more, specifically

- sit less, whenever reasonably possible

- sleep well

You can read the study itself here:

Want to know the best kind of exercise for brain health?

Check out our article about neuroscientist Dr. Suzuki, and what she has to say about it:

The Exercise That Protects Your Brain

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain – by Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed books about neurology before, and we always try to review books that bring something new/different. So, what makes this one stand out?

Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett, one of the world’s foremost neuroscientists, starts with an overview of how our unusual brain (definitely our species’ defining characteristic) came to be, and then devotes the rest of the book to mostly practical information.

She explains, in clear terms and without undue jargon, how the brain goes about such things as making constant predictions and useful assumptions about our environment, and reports these things to us as facts—which process is usually useful, and sometimes counterproductive.

We learn about how the apparently mystical trait of empathy works, in real flesh-and-blood terms, and why some kinds of empathy are more metabolically costly than others, and what that means for us all.

Unlike many such books, this one also looks at what is going on in the case of “different minds” that operate very dissimilarly to our own, and how this neurodiversity is important for our species.

Critically, she also looks at what else makes our brains stand out, the symphony of “5 Cs” that aren’t often found to the same extent all in the same species: creativity, communication, copying, cooperation, and compression. This latter being less obvious, but perhaps the most important; Dr. Feldman Barrett explains how we use this ability to layer summaries of our memories, perceptions, and assumptions, to allow us to think in abstractions—something that powers much of what we do that separates us from other animals.

Bottom line: if you’d like to learn more about that big wet organ between your ears, what it does for you, and how it goes about doing it, then this book gives a very practical foundation from which to build.

Click here to check out Seven and a Half Lessons about the Brain, and learn more about yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Are Electrolyte Supplements Worth It?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When To Take Electrolytes (And When We Shouldn’t!)

Any sports nutrition outlet will sell electrolyte supplements. Sometimes in the form of sports drinks that claim to be more hydrating than water, or tablets that can be dissolved in water to make the same. How do they work, and should we be drinking them?

What are electrolytes?

They’re called “electrolytes” because they are ionized particles (so, they have a positive or negative electrical charge, depending on which kind of ion they are) that are usually combined in the form of salts.

The “first halves” of the salts include:

- Sodium

- Potassium

- Calcium

- Magnesium

The “second halves” of the salts include:

- Chloride

- Phosphate

- Bicarbonate

- Nitrate

It doesn’t matter too much which way they’re combined, provided we get what we need. Specifically, the body needs them in a careful balance. Too much or too little, and bad things will start happening to us.

If we live in a temperate climate with a moderate lifestyle and a balanced diet, and have healthy working kidneys, usually our kidneys will keep them all in balance.

Why might we need to supplement?

Firstly, of course, you might have a dietary deficiency. Magnesium deficiency in particular is very common in North America, as people simply do not eat as much greenery as they ideally would.

But, also, you might sweat out your electrolytes, in which case, you will need to replace them.

In particular, endurance training and High Intensity Interval Training are likely to prompt this.

However… Are you in a rush? Because if not, you might just want to recover more slowly:

❝Vigorous exercise and warm/hot temperatures induce sweat production, which loses both water and electrolytes. Both water and sodium need to be replaced to re-establish “normal” total body water (euhydration).

This replacement can be by normal eating and drinking practices if there is no urgency for recovery.

But if rapid recovery (<24 h) is desired or severe hypohydration (>5% body mass) is encountered, aggressive drinking of fluids and consuming electrolytes should be encouraged to facilitate recovery❞

Source: Fluid and electrolyte needs for training, competition, and recovery

Should we just supplement anyway, as a “catch-all” to be sure?

Probably not. In particular, it is easy to get too much sodium in one’s diet, let alone by supplementation.And, oversupplementation of calcium is very common, and causes its own health problems. See:

To look directly to the science on this one, we see a general consensus amongst research reviews: “this is complicated and can go either way depending on what else people are doing”:

- Trace minerals intake: risks and benefits for cardiovascular health

- Electrolyte minerals intake and cardiovascular health

Well, that’s not helpful. Any clearer pointers?

Yes! Researchers Latzka and Mountain put together a very practical list of tips. Rather, they didn’t put it as a list, but the following bullet points are information extracted directly from their abstract, though we’ve also linked the full article below:

- It is recommended that individuals begin exercise when adequately hydrated.

- This can be facilitated by drinking 400 mL to 600 mL of fluid 2 hours before beginning exercise and drinking sufficient fluid during exercise to prevent dehydration from exceeding 2% body weight.

- A practical recommendation is to drink small amounts of fluid (150-300 mL) every 15 to 20 minutes of exercise, varying the volume depending on sweating rate.

- During exercise lasting less than 90 minutes, water alone is sufficient for fluid replacement

- During prolonged exercise lasting longer than 90 minutes, commercially available carbohydrate electrolyte beverages should be considered to provide an exogenous carbohydrate source to sustain carbohydrate oxidation and endurance performance.

- Electrolyte supplementation is generally not necessary because dietary intake is adequate to offset electrolytes lost in sweat and urine; however, during initial days of hot-weather training or when meals are not calorically adequate, supplemental salt intake may be indicated to sustain sodium balance.

Source: Water and electrolyte requirements for exercise

Bonus tip:

We’ve talked before about the specific age-related benefits of creatine supplementation, but if you’re doing endurance training or HIIT, you might also want to consider a creatine-electrolyte combination sports drink (even if you make it yourself):

Where can I get electrolyte supplements?

They’re easy to find in any sports nutrition store, or you can buy them online; here’s an example product on Amazon for your convenience

You can also opt for natural and/or homemade electrolyte drinks:

Healthline | 8 Healthy Drinks Rich in Electrolytes

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Hormones & Health, Beyond The Obvious

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Wholesome Health

This is Dr. Sara Gottfried, who some decades ago got her MD from Harvard and specialized as an OB/GYN at MIT. She’s since then spent the more recent part of her career educating people (mostly: women) about hormonal health, precision, functional, & integrative medicine, and the importance of lifestyle medicine in general.

What does she want us to know?

Beyond “bikini zone health”

Dr. Gottfried urges us to pay attention to our whole health, in context.

“Women’s health” is often thought of as what lies beneath a bikini, and if it’s not in those places, then we can basically treat a woman like a man.

And that’s often not actually true—because hormones affect every living cell in our body, and as a result, while prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women (specifically, those who are not on HRT) may share a few more similarities with boys and men of similar respective ages, for most people at most ages, men and women are by default quite different metabolically—which is what counts for a lot of diseases! And note, that difference is not just “faster” or “slower””, but is often very different in manner also.

That’s why, even in cases where incidence of disease is approximately similar in men and women when other factors are controlled for (age, lifestyle, medical history, etc), the disease course and response to treatment may vary considerable. For a strong example of this, see for example:

- The well-known: Heart Attack: His & Hers ← most people know these differences exist, but it’s always good to brush up on what they actually are

- The less-known: Statins: His & Hers ← most people don’t know these differences exist, and it pays to know, especially if you are a woman or care about one

Nor are brains exempt from his…

The female brain (kinda)

While the notion of an anatomically different brain for men and women has long since been thrown out as unscientific phrenology, and the idea of a genetically different brain is… Well, it’s an unreliable indicator, because technically the cells will have DNA and that DNA will usually (but not always; there are other options) have XX or XY chromosomes, which will usually (but again, not always) match apparent sex (in about 1/2000 cases there’s a mismatch, which is more common than, say, red hair; sometimes people find out about a chromosomal mismatch only later in life when getting a DNA test for some unrelated reason), and in any case, even for most of us, the chromosomal differences don’t count for much outside of antenatal development (telling the default genital materials which genitals to develop into, though this too can get diverted, per many intersex possibilities, which is also a lot more common than people think) or chromosome-specific conditions like colorblindness…

The notion of a hormonally different brain is, in contrast to all of the above, a reliable and easily verifiable thing.

See for example:

Alzheimer’s Sex Differences May Not Be What They Appear

Dr. Gottfried urges us to take the above seriously!

Because, if women get Alzheimer’s much more commonly than men, and the disease progresses much more quickly in women than men, but that’s based on postmenopausal women not on HRT, then that’s saying “Women, without women’s usual hormones, don’t do so well as men with men’s usual hormones”.

She does, by the way, advocate for bioidentical HRT for menopausal women, unless contraindicated for some important reason that your doctor/endocrinologist knows about. See also:

Menopausal HRT: A Tale Of Two Approaches (Bioidentical vs Animal)

The other very relevant hormone

…that Dr. Gottfried wants us to pay attention to is insulin.

Or rather, its scrubbing enzyme, the prosaically-named “insulin-degrading enzyme”, but it doesn’t only scrub insulin. It also scrubs amyloid beta—yes, the same that produces the amyloid beta plaques in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s. And, there’s only so much insulin-degrading enzyme to go around, and if it’s all busy breaking down excess insulin, there’s not enough left to do the other job too, and thus can’t break down amyloid beta.

In other words: to fight neurodegeneration, keep your blood sugars healthy.

This may actually work by multiple mechanisms besides the amyloid hypothesis, by the way:

The Surprising Link Between Type 2 Diabetes & Alzheimer’s

Want more from Dr. Gottfried?

You might like this interview with Dr. Gottfried by Dr. Benson at the IMCJ:

Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal | Conversations with Sara Gottfried, MD

…in which she discusses some of the things we talked about today, and also about her shift from a pharmaceutical-heavy approach to a predominantly lifestyle medicine approach.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: