No, COVID-19 vaccines don’t cause ‘turbo cancer’

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines do not cause “turbo cancer” or contain SV40, a virus that has been suspected of causing cancer.

- There is no link between rising cancer rates and COVID-19 vaccines.

- Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines is a safe, free way to support long-term health.

Myths that COVID-19 vaccines cause cancer have been circulating since the vaccines were first developed. These false claims resurfaced last month after Princess Kate Middleton announced that she is undergoing cancer treatment, with some vaccine opponents falsely claiming Middleton has a “turbo cancer” caused by COVID-19 vaccines.

Here’s what we know: “Turbo cancer” is a made-up term for a fake phenomenon, and there is strong evidence that COVID-19 vaccines do not cause cancer or increase cancer risk.

Read on to learn how to recognize false claims about COVID-19 vaccines and cancer.

Do COVID-19 vaccines contain cancer-causing ingredients?

No. Some vaccine opponents claim that COVID-19 vaccines contain SV40, a virus that has been suspected of causing cancer. This claim is false.

A piece of SV40’s DNA sequence—called a “promoter”—was used as starting material to develop COVID-19 vaccines, but the virus itself is not present in the vaccines. The promoter does not contain the part of the virus that enters the cell nucleus, so it poses no risk.

COVID-19 vaccines and their ingredients have been rigorously studied in millions of people worldwide and have been determined to be safe. The National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society agree that COVID-19 vaccines do not increase cancer risk or accelerate cancer growth.

Why are cancer rates rising in the U.S.?

Since the 1990s, cancer rates have been on the rise globally and in the U.S., most notably in people under 50. Increased cancer screening may partially explain the rising number of cancer diagnoses. Exposure to air pollution and lifestyle factors like tobacco use, alcohol use, and diet may also be contributing factors.

What are the benefits of staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines?

Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines is a safe way to protect our long-term health. COVID-19 vaccines prevent severe illness, hospitalization, death, and long COVID.

The CDC says staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines is a safer and more reliable way to build protection against COVID-19 than getting sick from COVID-19.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gut-Healthy Sunset Soup

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

So-called for its gut-healthy ingredients, and its flavor profile being from the Maghreb (“Sunset”) region, the western half of the N. African coast.

You will need

- 1 can chickpeas (do not drain)

- 1 cup low-sodium vegetable stock

- 1 small onion, finely chopped

- 1 carrot, finely chopped

- 2 tbsp sauerkraut, drained and chopped (yes, it is already chopped, but we want it chopped smaller so it can disperse evenly in the soup)

- 2 tbsp tomato paste

- 1 tbsp harissa paste (adjust per your heat preference)

- 1 tbsp ras el-hanout

- ¼ bulb garlic, crushed

- Juice of ½ lemon

- ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Optional: herb garnish; we recommend cilantro or flat-leaf parsley

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat a little oil in a sauté pan or similar (something suitable for combination cooking, as we’ll be frying first and then adding liquids), and fry the onion and carrot until the onion is soft and translucent; about 5 minutes.

2) Stir in the garlic, tomato paste, harissa paste, and ras el-hanout, and fry for a further 1 minute.

3) Add the remaining ingredients* except the lemon juice. Bring to the boil and then simmer for 5 minutes.

*So yes, this includes adding the “chickpea water” also called “aquafaba”; it adds flavor and also gut-healthy fiber in the form of oligosaccharides and resistant starches, which your gut microbiota can use to make short-chain fatty acids, which improve immune function and benefit the health in more ways than we can reasonably mention as a by-the-way in a recipe.

4) Stir in the lemon juice, and serve, adding a herb garnish if you wish.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← today’s recipe scored 5/5 of these, plus quite a few more! Remember that ras el-hanout is a spice blend, so if you’re thinking “wait, where’s the…?” then it’s in the ras el-hanout 😉

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More ← not to be underestimated!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Easy Ways To Fix Brittle, Dry, Wiry Hair

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Sam Ellis, a dermatologist, specializes in skin, hair, and nail care—and she’s here with professional knowledge:

Tackling the problem at the root

As we age, hair becomes less shiny, more brittle, coarse, wiry, or gray. More concerningly for many, hair thinning and shedding increases due to shortened growth phases and hormonal changes.

The first set of symptoms there are largely because sebum production decreases, leading to dry hair. It’s worth bearing in mind though, that factors like UV radiation, smoking, stress, and genetics contribute to hair aging too. So while we can’t do much about genetics, the modifiable factors are worth addressing.

Menopause and the corresponding “andropause” impact hair health, and hormonal shifts, not just aging, drive many hair changes. Which is good to know, because it means that HRT (mostly: topping up estrogen or testosterone as appropriate) can make a big difference. Additionally, topical/oral minoxidil and DHT blockers (such as finasteride or dutasteride) can boost hair density. These things come with caveats though, so do research any possible treatment plan before embarking on it, to be sure you are comfortable with all aspects of it—including that if you use minoxidil, while on the one hand it indeed works wonders, on the other hand, you’ll then have to keep using minoxidil for the rest of your life or your hair will fall out when you stop. So, that’s a commitment to be thought through before beginning.

Nutritional deficiencies (iron, zinc, vitamin D) and insufficient protein intake hinder hair growth, so ensure proper nutrition, with sufficient protein and micronutrients.

While we’re on the topic of “from the inside” things: take care to manage stress healthily, as stress negatively affects hair health.

Now, as for “from the outside”…

Dr. Ellis recommends moisturizing shampoos/conditioners; Virtue and Dove brands she mentions positively. She also recommends bond repair products (such as K18 and Olaplex) that restore hair integrity, and heat protectants (she recommends: Unite 7 Seconds) as well as hair oils in general that improve hair condition.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

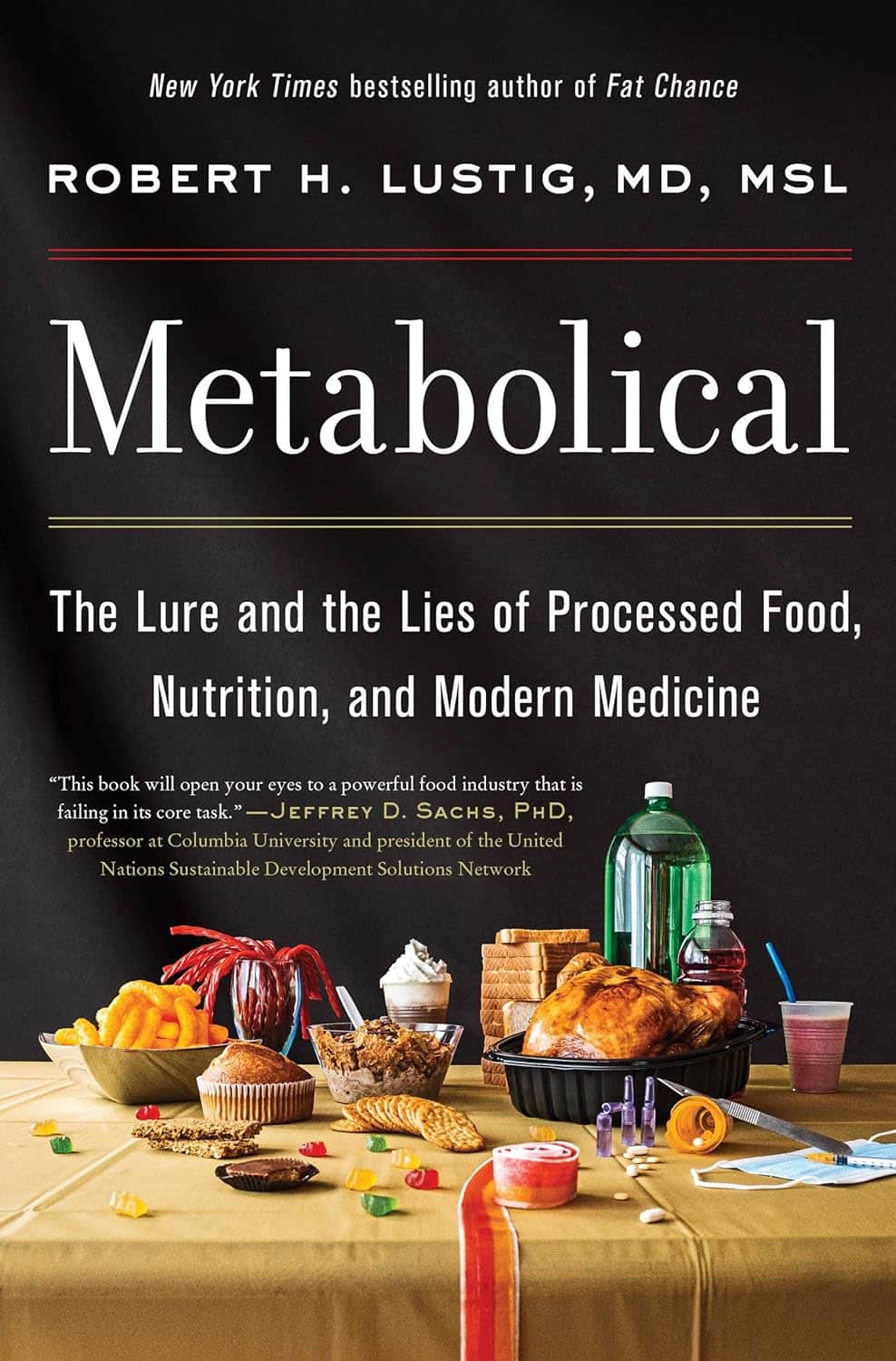

Metabolical – by Dr. Robert Lustig

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The premise of this book itself is not novel: processed food is bad, food giants lie to us, and eating better makes us less prone to disease (especially metabolic disease).

What this book does offer that’s less commonly found is a comprehensive guide, a walkthrough of each relevant what and why and how, with plenty of good science and practical real-world examples.

In terms of unique selling points, perhaps the greatest strength of this book is its focus on two things in particular that affect many aspects of health: looking after our liver, and looking after our gut.

The style is… A little dramatic perhaps, but that’s just the style; there’s no hyperbole, he is stating well-established scientific facts.

Bottom line: very much of chronic disease would be a lot less diseasey if we all ate with these aspects of our health in mind. This book’s a comprehensive guide to that.

Click here to check out Metabolical, and let food be thy medicine!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Blind Spots – by Dr. Marty Makary

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From the time the US recommended not giving peanuts to infants for the first three years of life “in order to avoid peanut allergies” (whereupon non-exposure to peanuts early in life led to, instead, an increase in peanut allergies and anaphylactic incidents), to the time the US recommended not taking HRT on the strength of the claim that “HRT causes breast cancer” (whereupon the reduced popularity of HRT led to, instead, an increase in breast cancer incidence and mortality), to many other such incidents of very bad public advice being given on the strength of a single badly-misrepresented study (for each respective thing), Dr. Makary puts the spotlight on what went wrong.

This is important, because this is not just a book of outrage, exclaiming “how could this happen?!”, but rather instead, is a book of inquisition, asking “how did this happen?”, in such a way that we the reader can spot similar patterns going forwards.

Oftentimes, this is a simple matter of having a basic understanding of statistics, and checking sources to see if the dataset really supports what the headlines are claiming—and indeed, whether sometimes it suggests rather the opposite.

The style is a little on the sensationalist side, but it’s well-supported with sound arguments, good science, and clear mathematics.

Bottom line: if you’d like to improve your scientific literacy, this book is an excellent illustrative guide.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

3 signs your diet is causing too much muscle loss – and what to do about it

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When trying to lose weight, it’s natural to want to see quick results. So when the number on the scales drops rapidly, it seems like we’re on the right track.

But as with many things related to weight loss, there’s a flip side: rapid weight loss can result in a significant loss of muscle mass, as well as fat.

So how you can tell if you’re losing too much muscle and what can you do to prevent it?

EvMedvedeva/Shutterstock Why does muscle mass matter?

Muscle is an important factor in determining our metabolic rate: how much energy we burn at rest. This is determined by how much muscle and fat we have. Muscle is more metabolically active than fat, meaning it burns more calories.

When we diet to lose weight, we create a calorie deficit, where our bodies don’t get enough energy from the food we eat to meet our energy needs. Our bodies start breaking down our fat and muscle tissue for fuel.

A decrease in calorie-burning muscle mass slows our metabolism. This quickly slows the rate at which we lose weight and impacts our ability to maintain our weight long term.

How to tell you’re losing too much muscle

Unfortunately, measuring changes in muscle mass is not easy.

The most accurate tool is an enhanced form of X-ray called a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan. The scan is primarily used in medicine and research to capture data on weight, body fat, muscle mass and bone density.

But while DEXA is becoming more readily available at weight-loss clinics and gyms, it’s not cheap.

There are also many “smart” scales available for at home use that promise to provide an accurate reading of muscle mass percentage.

Some scales promise to tell us our muscle mass. Lee Charlie/Shutterstock However, the accuracy of these scales is questionable. Researchers found the scales tested massively over- or under-estimated fat and muscle mass.

Fortunately, there are three free but scientifically backed signs you may be losing too much muscle mass when you’re dieting.

1. You’re losing much more weight than expected each week

Losing a lot of weight rapidly is one of the early signs that your diet is too extreme and you’re losing too much muscle.

Rapid weight loss (of more than 1 kilogram per week) results in greater muscle mass loss than slow weight loss.

Slow weight loss better preserves muscle mass and often has the added benefit of greater fat mass loss.

One study compared people in the obese weight category who followed either a very low-calorie diet (500 calories per day) for five weeks or a low-calorie diet (1,250 calories per day) for 12 weeks. While both groups lost similar amounts of weight, participants following the very low-calorie diet (500 calories per day) for five weeks lost significantly more muscle mass.

2. You’re feeling tired and things feel more difficult

It sounds obvious, but feeling tired, sluggish and finding it hard to complete physical activities, such as working out or doing jobs around the house, is another strong signal you’re losing muscle.

Research shows a decrease in muscle mass may negatively impact your body’s physical performance.

3. You’re feeling moody

Mood swings and feeling anxious, stressed or depressed may also be signs you’re losing muscle mass.

Research on muscle loss due to ageing suggests low levels of muscle mass can negatively impact mental health and mood. This seems to stem from the relationship between low muscle mass and proteins called neurotrophins, which help regulate mood and feelings of wellbeing.

So how you can do to maintain muscle during weight loss?

Fortunately, there are also three actions you can take to maintain muscle mass when you’re following a calorie-restricted diet to lose weight.

1. Incorporate strength training into your exercise plan

While a broad exercise program is important to support overall weight loss, strength-building exercises are a surefire way to help prevent the loss of muscle mass. A meta-analysis of studies of older people with obesity found resistance training was able to prevent almost 100% of muscle loss from calorie restriction.

Relying on diet alone to lose weight will reduce muscle along with body fat, slowing your metabolism. So it’s essential to make sure you’ve incorporated sufficient and appropriate exercise into your weight-loss plan to hold onto your muscle mass stores.

Strength-building exercises help you retain muscle. BearFotos/Shutterstock But you don’t need to hit the gym. Exercises using body weight – such as push-ups, pull-ups, planks and air squats – are just as effective as lifting weights and using strength-building equipment.

Encouragingly, moderate-volume resistance training (three sets of ten repetitions for eight exercises) can be as effective as high-volume training (five sets of ten repetitions for eight exercises) for maintaining muscle when you’re following a calorie-restricted diet.

2. Eat more protein

Foods high in protein play an essential role in building and maintaining muscle mass, but research also shows these foods help prevent muscle loss when you’re following a calorie-restricted diet.

But this doesn’t mean just eating foods with protein. Meals need to be balanced and include a source of protein, wholegrain carb and healthy fat to meet our dietary needs. For example, eggs on wholegrain toast with avocado.

3. Slow your weight loss plan down

When we change our diet to lose weight, we take our body out of its comfort zone and trigger its survival response. It then counteracts weight loss, triggering several physiological responses to defend our body weight and “survive” starvation.

Our body’s survival mechanisms want us to regain lost weight to ensure we survive the next period of famine (dieting). Research shows that more than half of the weight lost by participants is regained within two years, and more than 80% of lost weight is regained within five years.

However, a slow and steady, stepped approach to weight loss, prevents our bodies from activating defence mechanisms to defend our weight when we try to lose weight.

Ultimately, losing weight long-term comes down to making gradual changes to your lifestyle to ensure you form habits that last a lifetime.

At the Boden Group, Charles Perkins Centre, we are studying the science of obesity and running clinical trials for weight loss. You can register here to express your interest.

Nick Fuller, Charles Perkins Centre Research Program Leader, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

5 Ways To Naturally Boost The “Ozempic Effect”

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Jason Fung is perhaps most well-known for his work in functional medicine for reversing diabetes, and he’s once again giving us sound advice about metabolic hormone-hacking with dietary tweaks:

All about incretin

As you may gather from the thumbnail, this video is about incretin, a hormone group (the most well-known of which is GLP-1, as in GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide drugs such as Ozempic, Wegovy, etc) that slows down stomach emptying, which means a gentler blood sugar curve and feeling fuller for longer. It also acts on the hypothalmus, controlling appetite via the brain too (signalling fullness and reducing hunger).

Dr. Fung recommends 5 ways to increase incretin levels:

- Enjoy dietary fat: healthy kinds, please (e.g. nuts, seeds, eggs, etc—not fried foods), but this increases incretin levels more than carbs

- Enjoy protein: again, prompts higher incretin levels of promotes satiety

- Enjoy fiber: this is more about slowing digestion, but when it’s fermented in the gut into short-chain fatty acids, those too increase incretin secretion

- Enjoy bitter foods: these don’t actually affect incretin levels, but they can bind to incretin receptors, making the body “believe” that you got more incretin (think of it like a skeleton key that fits the lock that was designed to be opened by a different key)

- Enjoy turmeric: for its curcumin content, which increases GLP-1 levels specifically

For more information on each of these, here’s Dr. Fung himself:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Semaglutide for Weight Loss?

- Ozempic vs Five Natural Supplements

- How To Prevent And Reverse Type 2 Diabetes ← this was our “Expert Insights” feature on Dr. Fung’s work

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: