Cordyceps: Friend Or Foe?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cordyceps: friend or foe?

Cordyceps is a famously frightening fungus. It’s the one responsible for “zombie ants” and other zombie creatures, and it’s the basis for the existential threat to humanity in the TV show The Last of Us.

It’s a parasitic fungus that controls the central and peripheral nervous systems of its host, slowly replacing the host’s body, as well as growing distinctive spines that erupt out of the host’s body. Taking over motor functions, it compels the host to do two main things, which are to eat more food, and climb to a position that will be good to release spores from.

Fortunately, none of that matters to humans. Cordyceps does not (unlike in the TV show) affect humans that way.

What does Cordyceps do in humans?

Cordyceps (in various strains) is enjoyed as a health supplement, based on a long history of use in Traditional Chinese Medicine, and nowadays it’s coming under a scientific spotlight too.

The main health claims for it are:

- Against inflammation

- Against aging

- Against cancer

- For blood sugar management

- For heart health

- For exercise performance

Sounds great! What does the science say?

There’s a lot more science for the first three (which are all closely related to each other, and often overlapping in mechanism and effect).

So let’s take a look:

Against inflammation

The science looks promising for this, but studies so far have either been in vitro (cell cultures in petri dishes), or else murine in vivo (mouse studies), for example:

- Anti-inflammatory effects of Cordyceps mycelium in murine macrophages

- Cordyceps sinensis as an immunomodulatory agent

- Immunomodulatory functions of extracts from Cordyceps cicadae

- Cordyceps pruinosa inhibits in vitro and in vivo inflammatory mediators

In summary: we can see that it has anti-inflammatory properties for mice and in the lab; we’d love to see the results of studies done on humans, though. Also, while it has anti-inflammatory properties, it performed less well than commonly-prescribed anti-inflammatory drugs, for example:

❝C. militaris can modulate airway inflammation in asthma, but it is less effective than prednisolone or montelukast.❞

Against aging

Because examining the anti-aging effects of a substance requires measuring lifespans and repeating the experiment, anti-aging studies do not tend to be done on humans, because they would take lifetimes to perform. To this end, it’s inconvenient, but not a criticism of Cordyceps, that studies have been either mouse studies (short lifespan, mammals like us) or fruit fly studies (very short lifespan, genetically surprisingly similar to us).

The studies have had positive results, with typical lifespan extensions of 15–20%:

- The lifespan-extending effect of Cordyceps sinensis in normal mice

- Cordyceps sinensis oral liquid prolongs the lifespan of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster

- Anti-aging activity of polysaccharides from Cordyceps militaris

- Anti-aging effect of Cordyceps sinensis extract

Against cancer

Once again, the studies here have been in vitro, or murine in vivo. They do look good though:

In vitro (human cell cultures in a lab):

In vivo (mouse studies):

Summary of these is: Cordyceps quite reliably inhibits tumor growth in vitro (human cell cultures) and in vivo (mouse studies). However, trials in human cancer patients are so far conspicuous by their absence.

For blood sugar management

Cordyceps appears to mimic the action of insulin, without triggering insulin sensitivity. For example:

The anti-hyperglycemic activity of the fruiting body of Cordyceps in diabetic rats

There were some other rat/mouse studies with similar results. No studies in humans yet.

For heart health

Cordyceps contains adenosine. You may remember that caffeine owes part of its stimulant effect to blocking adenosine, the hormone that makes us feel sleepy. So in this way, Cordyceps partially does the opposite of what caffeine does, and may be useful against arrhythmia:

Cardiovascular protection of Cordyceps sinensis act partially via adenosine receptors

For exercise performance

A small (30 elderly participants) study found that Cordyceps supplementation improved VO2 max by 7% over the course of six weeks:

However, another small study (22 young athletes) failed to reproduce those results:

Cordyceps Sinensis supplementation does not improve endurance exercise performance

In summary…

Cordyceps almost certainly has anti-inflammation, anti-aging, and anti-cancer benefits.

Cordyceps may have other benefits too, but the evidence is thinner on the ground for those, so far.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Likely Are You To Live To 100?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How much hope can we reasonably have of reaching 100?

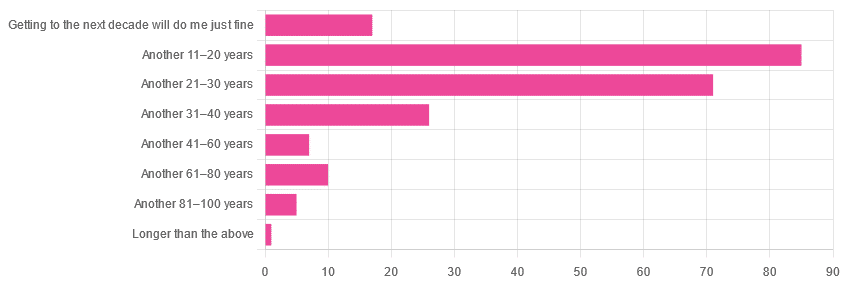

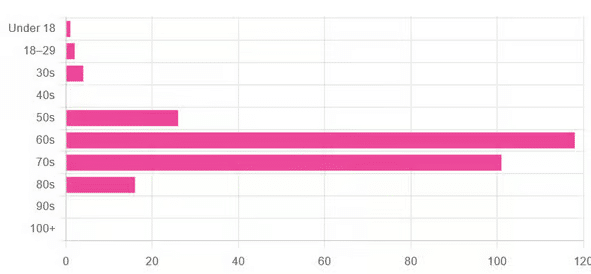

Yesterday, we asked you: assuming a good Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), how much longer do you hope to live?

We got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- A little over 38% of respondents hope to live another 11–20 years

- A little over 31% hope to live another 31–40 years

- A little over 7% will be content to make it to the next decade

- One (1) respondent hopes to live longer than an additional 100 years

This is interesting when we put it against our graph of how old our subscribers are:

…because it corresponds inversely, right down to the gap/dent in the 40s. And—we may hypothesize—that one person under 18 who hopes to live to 120, perhaps.

This suggests that optimism remains more or less constant, with just a few wobbles that would probably be un-wobbled with a larger sample size.

In other words: most of our education-minded, health-conscious subscriber-base hope to make it to the age of 90-something, while for the most part feeling that 100+ is overly optimistic.

Writer’s anecdote: once upon a time, I was at a longevity conference in Brussels, and a speaker did a similar survey, but by show of hands. He started low by asking “put your hands up if you want to live at least a few more minutes”. I did so, with an urgency that made him laugh, and say “Don’t worry; I don’t have a gun hidden up here!”

Conjecture aside… What does the science say about our optimism?

First of all, a quick recap…

To not give you the same information twice, let’s note we did an “aging mythbusting” piece already covering:

- Aging is inevitable: True or False?

- Aging is, and always will be, unstoppable: True or False?

- We can slow aging: True or False?

- It’s too early to worry about… / It’s too late to do anything about… True or False?

- We can halt aging: True or False?

- We can reverse aging: True or False?

- But those aren’t really being younger, we’ll still die when our time is up: True or False?

You can read the answers to all of those here:

Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

Now, onwards…

It is unreasonable to expect to live past 100: True or False?

True or False, depending on your own circumstances.

First, external circumstances: the modal average person in Hong Kong is currently in their 50s and can expect to live into their late 80s, while the modal average person in Gaza is 14 and may not expect to make it to 15 right now.

To avoid extremes, let’s look at the US, where the modal average person is currently in their 30s and can expect to live into their 70s:

United States Mortality Database

Now, before that unduly worries our many readers already in their 70s…

Next, personal circumstances: not just your health, but your socioeconomic standing. And in the US, one of the biggest factors is the kind of health insurance one has:

SOA Research Institute | Life Expectancy Calculator 2021

You may note that the above source puts all groups into a life expectancy in the 80s—whereas the previous source gave 70s.

Why is this? It’s because the SOA, whose primary job is calculating life insurance risks, is working from a sample of people who have, or are applying for, life insurance. So it misses out many people who die younger without such.

New advances in medical technology are helping people to live longer: True or False?

True, assuming access to those. Our subscribers are mostly in North America, and have an economic position that affords good access to healthcare. But beware…

On the one hand:

The number of people who live past the age of 100 has been on the rise for decades

On the other hand:

The average life expectancy in the U.S. has been on the decline for three consecutive years

COVID is, of course, largely to blame for that, though:

❝The decline of 1.8 years in life expectancy was primarily due to increases in mortality from COVID-19 (61.2% of the negative contribution).

The decline in life expectancy would have been even greater if not for the offsetting effects of decreases in mortality due to cancer (43.1%)❞

Source: National Vital Statistics Reports

The US stats are applicable to Canada, the UK, and Australia: True or False?

False: it’s not quite so universal. Differences in healthcare systems will account for a lot, but there are other factors too:

- Life expectancy in Canada fell for the 3rd year in a row. What’s happening?

- UK life expectancy lagging behind rest of G7 except the US

- Australians are living longer but what does it take to reach 100 years old?

Here’s an interesting (UK-based) tool that calculates not just your life expectancy, but also gives the odds of living to various ages (e.g. this writer was given odds of living to 87, 96, 100).

Check yours here:

Office of National Statistics | Life Expectancy Calculator

To finish on a cheery note…

Data from Italian centenarians suggests a “mortality plateau”:

❝The risk of dying leveled off in people 105 and older, the team reports online today in Science.

That means a 106-year-old has the same probability of living to 107 as a 111-year-old does of living to 112.

Furthermore, when the researchers broke down the data by the subjects’ year of birth, they noticed that over time, more people appear to be reaching age 105.❞

Pop-sci source: Once you hit this age, aging appears to stop

Actual paper: The plateau of human mortality: demography of longevity pioneers

Take care!

Share This Post

-

What To Leave Off Your Table (To Stay Off This Surgeon’s)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Why we eat too much (and how we can fix that)

This is Dr. Andrew Jenkinson. He’s a Consultant Surgeon specializing in the treatment of obesity, gallstones, hernias, heartburn and abdominal pain. He runs regular clinics in both London and Dubai. What he has to offer us today, though, is insight as to what’s on our table that puts us on his table, and how we can quite easily change that up.

So, why do we eat too much?

First things first: some metabolic calculations. No, we’re not going to require you to grab a calculator here… Your body does it for you!

Our body’s amazing homeostatic system (the system that does its best to keep us in the “Goldilocks Zone” of all our bodily systems; not too hot or too cold, not dehydrated or overhydrated, not hyperglycemic or hypoglycemic, blood pressure not too high or too low, etc, etc) keeps track of our metabolic input and output.

What this means: if we increase or decrease our caloric consumption, our body will do its best to increase or decrease our metabolism accordingly:

- If we don’t give it enough energy, it will try to conserve energy (first by slowing our activities; eventually by shutting down organs in a last-ditch attempt to save the rest of us)

- If we give it too much energy, it will try to burn it off, and what it can’t burn, it will store

In short: if we eat 10% or 20% more or less than usual, our body will try to use 10% to 20% more or less than usual, accordingly.

So… How does this get out of balance?

The problem is in how our system does that, and how we inadvertently trick it, to our detriment.

For a system to function, it needs at its most base level two things—a sensor and a switch:

- A sensor: to know what’s going on

- A switch: to change what it’s doing accordingly

Now, if we eat the way we’re evolved to—as hunter-gatherers, eating mostly fruit and vegetables, supplemented by animal products when we can get them—then our body knows exactly what it’s eating, and how to respond accordingly.

Furthermore, that kind of food takes some eating! Most fruit these days is mostly water and fiber; in those days it often had denser fiber (before agricultural science made things easier to eat), but either way, our body knows when we are eating fruit and how to handle that. Vegetables, similarly. Unprocessed animal products, again, the gut goes “we know what this is” and responds accordingly.

But modern ultra-processed foods with trans-fatty acids, processed sugar and flour?

These foods zip calories straight into our bloodstream like greased lightning. We get them so quickly so easily and in such great caloric density, that our body doesn’t have the chance to count them on the way in!

What this means is: the body has no idea what it’s just consumed or how much or what to do with it, and doesn’t adjust our metabolism accordingly.

Bottom line:

Evolutionarily speaking, your body has no idea what ultra-processed food is. If you skip it and go for whole foods, you can, within the bounds of reason, eat what you like and your body will handle it by adjusting your metabolism accordingly.

Now, advising you “avoid ultra-processed foods and eat whole foods” was probably not a revelation in and of itself.

But: sometimes knowing a little more about the “why” makes the difference when it comes to motivation.

Want to know more about Dr. Jenkinson’s expert insights on this topic?

If you like, you can check out his website here—he has a book too

Why We Eat (Too Much) – Dr. Andrew Jenkinson on the Science of Appetite

Share This Post

-

What are heart rate zones, and how can you incorporate them into your exercise routine?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you spend a lot of time exploring fitness content online, you might have come across the concept of heart rate zones. Heart rate zone training has become more popular in recent years partly because of the boom in wearable technology which, among other functions, allows people to easily track their heart rates.

Heart rate zones reflect different levels of intensity during aerobic exercise. They’re most often based on a percentage of your maximum heart rate, which is the highest number of beats your heart can achieve per minute.

But what are the different heart rate zones, and how can you use these zones to optimise your workout?

The three-zone model

While there are several models used to describe heart rate zones, the most common model in the scientific literature is the three-zone model, where the zones may be categorised as follows:

- zone 1: 55%–82% of maximum heart rate

- zone 2: 82%–87% of maximum heart rate

- zone 3: 87%–97% of maximum heart rate.

If you’re not sure what your maximum heart rate is, it can be calculated using this equation: 208 – (0.7 × age in years). For example, I’m 32 years old. 208 – (0.7 x 32) = 185.6, so my predicted maximum heart rate is around 186 beats per minute.

There are also other models used to describe heart rate zones, such as the five-zone model (as its name implies, this one has five distinct zones). These models largely describe the same thing and can mostly be used interchangeably.

What do the different zones involve?

The three zones are based around a person’s lactate threshold, which describes the point at which exercise intensity moves from being predominantly aerobic, to predominantly anaerobic.

Aerobic exercise uses oxygen to help our muscles keep going, ensuring we can continue for a long time without fatiguing. Anaerobic exercise, however, uses stored energy to fuel exercise. Anaerobic exercise also accrues metabolic byproducts (such as lactate) that increase fatigue, meaning we can only produce energy anaerobically for a short time.

On average your lactate threshold tends to sit around 85% of your maximum heart rate, although this varies from person to person, and can be higher in athletes.

Wearable technology has taken off in recent years. Ketut Subiyanto/Pexels In the three-zone model, each zone loosely describes one of three types of training.

Zone 1 represents high-volume, low-intensity exercise, usually performed for long periods and at an easy pace, well below lactate threshold. Examples include jogging or cycling at a gentle pace.

Zone 2 is threshold training, also known as tempo training, a moderate intensity training method performed for moderate durations, at (or around) lactate threshold. This could be running, rowing or cycling at a speed where it’s difficult to speak full sentences.

Zone 3 mostly describes methods of high-intensity interval training, which are performed for shorter durations and at intensities above lactate threshold. For example, any circuit style workout that has you exercising hard for 30 seconds then resting for 30 seconds would be zone 3.

Striking a balance

To maximise endurance performance, you need to strike a balance between doing enough training to elicit positive changes, while avoiding over-training, injury and burnout.

While zone 3 is thought to produce the largest improvements in maximal oxygen uptake – one of the best predictors of endurance performance and overall health – it’s also the most tiring. This means you can only perform so much of it before it becomes too much.

Training in different heart rate zones improves slightly different physiological qualities, and so by spending time in each zone, you ensure a variety of benefits for performance and health.

So how much time should you spend in each zone?

Most elite endurance athletes, including runners, rowers, and even cross-country skiers, tend to spend most of their training (around 80%) in zone 1, with the rest split between zones 2 and 3.

Because elite endurance athletes train a lot, most of it needs to be in zone 1, otherwise they risk injury and burnout. For example, some runners accumulate more than 250 kilometres per week, which would be impossible to recover from if it was all performed in zone 2 or 3.

Of course, most people are not professional athletes. The World Health Organization recommends adults aim for 150–300 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week, or 75–150 minutes of vigorous exercise per week.

If you look at this in the context of heart rate zones, you could consider zone 1 training as moderate intensity, and zones 2 and 3 as vigorous. Then, you can use heart rate zones to make sure you’re exercising to meet these guidelines.

What if I don’t have a heart rate monitor?

If you don’t have access to a heart rate tracker, that doesn’t mean you can’t use heart rate zones to guide your training.

The three heart rate zones discussed in this article can also be prescribed based on feel using a simple 10-point scale, where 0 indicates no effort, and 10 indicates the maximum amount of effort you can produce.

With this system, zone 1 aligns with a 4 or less out of 10, zone 2 with 4.5 to 6.5 out of 10, and zone 3 as a 7 or higher out of 10.

Heart rate zones are not a perfect measure of exercise intensity, but can be a useful tool. And if you don’t want to worry about heart rate zones at all, that’s also fine. The most important thing is to simply get moving.

Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Just Be Well – by Dr. Thomas Sult

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Firstly, what this is not: a “think yourself well” book. It’s not about just deciding to be well.

Rather, it’s about ensuring the foundations of wellness, from which the rest of good health can spring, and notably, an absence of chronic illness. In essence: enjoying chronic good health.

The prescription here is functional medicine, which stands on the shoulders of lifestyle medicine. This latter is thus briefly covered and the basics presented, but most of the book is about identifying the root causes of disease and eliminating them one by one, by taking into account the functions of the body’s processes, both in terms of pathogenesis (and thus, seeking to undermine that) and in terms of correct functioning (i.e., good health).

While the main focus of the book is on health rather than disease, he does cover a number of very common chronic illnesses, and how even in those cases where they cannot yet be outright cured, there’s a lot more that can be done for them than “take two of these and call your insurance company in the morning”, when the goal is less about management of symptoms (though that is also covered) and more about undercutting causes, and ensuring that even if one thing goes wrong, it doesn’t bring the entire rest of the system down with it (something that often happens without functional medicine).

The style is clear, simple, and written for the layperson without unduly dumbing things down.

Bottom line: if you would like glowingly good health regardless of any potential setbacks, this book can help your body do what it needs to for you.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What You Don’t Know Can Kill You

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Knowledge Is Power!

This is Dr. Simran Malhotra. She’s triple board-certified (in lifestyle medicine, internal medicine, and palliative care), and is also a health and wellness coach.

What does she want us to know?

Three things:

Wellness starts with your mindset

Dr. Malhotra shifted her priorities a lot during the initial and perhaps most chaotic phase of the COVID pandemic:

❝My husband, a critical care physician, was consumed in the trenches of caring for COVID patients in the ICU. I found myself knee-deep in virtual meetings with families whose loved ones were dying of severe COVID-related illnesses. Between the two of us, we saw more trauma, suffering, and death, than we could have imagined.

The COVID-19 pandemic opened my eyes to how quickly life can change our plans and reinforced the importance of being mindful of each day. Harnessing the power to make informed decisions is important, but perhaps even more important is focusing on what is in our control and taking action, even if it is the tiniest step in the direction we want to go!❞

~ Dr. Simran Malhotra

We can only make informed decisions if we have good information. That’s one of the reasons we try to share as much information as we can each day at 10almonds! But a lot will always depend on personalized information.

There are one-off (and sometimes potentially life-saving) things like health genomics:

The Real Benefit Of Genetic Testing

…but also smaller things that are informative on an ongoing basis, such as keeping track of your weight, your blood pressure, your hormones, and other metrics. You can even get fancy:

Track Your Blood Sugars For Better Personalized Health

Lifestyle is medicine

It’s often said that “food is medicine”. But also, movement is medicine. Sleep is medicine. In short, your lifestyle is the most powerful medicine that has ever existed.

Lifestyle encompasses very many things, but fortunately, there’s an “80:20 rule” in play that simplifies it a lot because if you take care of the top few things, the rest will tend to look after themselves:

These Top Few Things Make The Biggest Difference To Overall Health

Gratitude is better than fear

If we receive an unfavorable diagnosis (and let’s face it, most diagnoses are unfavorable), it might not seem like something to be grateful for.

But it is, insofar as it allows us to then take action! The information itself is what gives us our best chance of staying safe. And if that’s not possible e.g. in the worst case scenario, a terminal diagnosis, (bearing in mind that one of Dr. Malhotra’s three board certifications is in palliative care, so she sees this a lot), it at least gives us the information that allows us to make the best use of whatever remains to us.

See also: Managing Your Mortality

Which is very important!

…and/but possibly not the cheeriest note on which to end, so when you’ve read that, let’s finish today’s main feature on a happier kind of gratitude:

How To Get Your Brain On A More Positive Track (Without Toxic Positivity)

Want to hear more from Dr. Malhotra?

Showing how serious she is about how our genes do not determine our destiny and knowledge is power, here she talks about her “previvor’s journey”, as she puts it, with regard to why she decided to have preventative cancer surgery in light of discovering her BRCA1 genetic mutation:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Pumpkin Protein Crackers

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ten of these (give or take what size you make them) will give you the 20g protein that most people’s body’s can use at a time. Five of these plus some of one of the dips we list at the bottom will also do it:

You will need

- 1 cup chickpea flour (also called gram flour or garbanzo bean flour)

- 2 tbsp pumpkin seeds

- 1 tbsp chia seeds

- 1 tsp baking powder

- ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

- 2 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 350℉ / 180℃.

2) Combine the dry ingredients in a mixing bowl, and mix thoroughly.

3) Add the oil, and mix thoroughly.

4) Add water, 1 tbsp at a time, mixing thoroughly until the mixture comes together and you have a dough ball. You’ll probably need 3–4 tbsp in total, but do add them one at a time.

5) Roll out the dough as thinly and evenly as you can between two sheets of baking paper. Remove the top layer of the paper, and slice the dough into squares or triangles. You could use a cookie-cutter to make other shapes if you like, but then you’ll need to repeat the rolling to use up the offcuts. So we recommend squares or triangles at least for your first go.

6) Bake them in the oven for 12–15 minutes or until golden and crispy. Enjoy immediately or keep in an airtight container.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some things to go with what we have going on today:

- Muhammara ← this is a very nutritionally-dense dip (not to mention tasty; seriously, check out these flavors)

- Hero Homemade Hummus ← a classic

- Plant-Based Healthy Cream Cheese ← also a very respectable option

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: