Ageless Aging – by Maddy Dychtwald

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Maddy Dychtwald, herself 73, has spent her career working in the field of aging. She’s not a gerontologist or even a doctor, but she’s nevertheless been up-to-the-ears in the industry for decades, mostly as an organizer, strategist, facilitator, and so forth. As such, she’s had her finger on the pulse of the healthy longevity movement for a long time.

This book was written to address a problem, and the problem is: lifespan is increasing (especially for women), but healthspan has not been keeping up the pace.

In other words: people (especially women) are living longer, but often with more health problems along the way than before.

And mostly, it’s for lack of information (or sometimes: too much competing incorrect information).

Fortunately, information is something that a woman in Dychtwald’s position has an abundance of, because she has researchers and academics in many fields on speed-dial and happy to answer her questions (we get a lot of input from such experts throughout the book—which is why this book is so science-based, despite the author not being a scientist).

The book answers a lot of important questions beyond the obvious “what diet/exercise/sleep/supplements/etc are best for healthy aging” (spoiler: it’s quite consistent with the things we recommend here, because guess what, science is science), questions like how best to prepare for this that or the other, how to get a head start on preventative healthcare for some things, how to avoid being a burden to our families (one can argue that families are supposed to look after each other, but still, it’s a legitimate worry for many, and understandably so), and even how to balance the sometimes conflicting worlds of health and finances.

Unlike many authors, she also talks about the different kinds of aging, and tackles each of them separately and together. We love to see it!

Bottom line: this book is a very good one-stop-shop for all things healthy aging. It’s aimed squarely at women, but most advice goes for men the same too, aside from the section on hormones and such.

Click here to check out Ageless Aging, and plan your future!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Lucid Dreaming: How To Do It, & Why

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Lucid Dreaming: Methods & Uses

We’ve written about dreaming more generally before:

Today we’re going to be talking more about a subject we’ve only touched on previously: lucid dreaming

What it is: lucid dreaming is the practice of being mentally awake while dreaming, with awareness that it is a dream, and control over the dream.

Why is it useful? Beyond simply being fun, it can banish nightmares, it can improve one’s relationship with sleep (always something to look forward to, and sleep doesn’t feel like a waste of time at all!), and it can allow for exploring a lot of things that can’t easily be explored otherwise—which can be quite therapeutic.

How to do it

There are various ways to induce lucid dreaming, but the most common and “entry-level” method is called Mnemonic-Induced Lucid Dreaming (MILD).

MILD involves having some means of remembering what one has forgotten, i.e., that one is dreaming. To break it down further, first we’ll need to learn how to perform a reality check. Again, there are many of these, but one of the simplest is to ask yourself:

How did I get here?

- If you can retrace your steps with relative ease and the story of how you got here does not sound too much like a dream sequence, you are probably not dreaming.

- If you are dreaming, however, chances are that nothing actually led to where you are now; you just appeared here.

Other reality checks include checking whether books, clocks, and/or lightswitches work as they should—all are notorious for often being broken in dreams; books have gibberish or missing or repeated text; clocks do not tell the correct time and often do not even tell a time that could be real (e.g: 07:72), and lightswitches may turn a light on/off without actually changing the level of illumination in the room.

Now, a reality check is only useful if you actually perform it, so this is where MILD comes in.

You need to make a habit of doing a reality check frequently. Whenever you remember, it’s a good time to do a reality check, but you should also try tying it to something. Many people use a red light, because then they can also use a timed red light during the night to subconsciously cue them that they are dreaming. But it could be as simple as “whenever I go to the bathroom, I do a reality check”.

With this in mind, a fun method that has extra benefits is to try to use a magical power, such as psychokinesis. If (while fully awake) whenever you go to pick up some object you imagine it just wooshing magically to meet your hand halfway, then at some point you’ll instinctively do that while dreaming, and it’ll stand a good chance of working—and thus cluing you in that you are dreaming.

How to stay lucid

When you awaken within a dream (i.e. become lucid), there’s a good chance of one of two things happening quickly:

- you forget again

- you wake up

So when you realize you are dreaming, do two things at once:

- verbally repeat to yourself “I am dreaming now”. This will help stretch your awareness from one second to the next.

- look at your hands, and touch things, especially the floor and/or walls. This will help to ground you within the dream.

Things to do while lucid

Flying is a good fun entry-level activity; it’s very common to initially find it difficult though, and only be able to lift up very slightly before gently falling down, or things like that. A good tip is: instead of trying to move yourself, you stay still and move the dream around you, as though you are rotating a 3D model (because guess what: you are).

Confronting your nightmares and/or general fears is a good thing for many. Think, while you’re still awake during the day, about what you would do about the source/trigger of your fear if you had magical powers. Whatever you choose, keep it consistent for now, because this is about habit-forming.

Example: let’s say there’s a person from your past who appears in your nightmares. Let’s say your chosen magic would be “I would cause the ground to open up, swallow them, and close again behind them”. Vividly imagine that whenever they come to mind while you are awake, and when you encounter them next in a nightmare, you’ll remember to do exactly that, and it’ll work.

Learning about your own subconscious is a more advanced activity, but once you’re used to lucid dreaming, you can remember that everything in there is an internal projection of your own mind, so you can literally talk to parts of your subconscious, including past versions of yourself, or singular parts of your greater-whole personality, as per IFS:

Take Care Of Your “Unwanted” Parts Too!

Want to know more?

You might like to read:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Keep Inflammation At Bay

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How to Prevent (or Reduce) Inflammation

You asked us to do a main feature on inflammation, so here we go!

Before we start, it’s worth noting an important difference between acute and chronic inflammation:

- Acute inflammation is generally when the body detects some invader, and goes to war against it. This (except in cases such as allergic responses) is usually helpful.

- Chronic inflammation is generally when the body does a civil war. This is almost never helpful.

We’ll be tackling the latter, which frees up your body’s resources to do better at the former.

First, the obvious…

These five things are as important for this as they are for most things:

- Get a good diet—the Mediterranean diet is once again a top-scorer

- Exercise—move and stretch your body; don’t overdo it, but do what you reasonably can, or the inflammation will get worse.

- Reduce (or ideally eliminate) alcohol consumption. When in pain, it’s easy to turn to the bottle, and say “isn’t this one of red wine’s benefits?” (it isn’t, functionally*). Alcohol will cause your inflammation to flare up like little else.

- Don’t smoke—it’s bad for everything, and that goes for inflammation too.

- Get good sleep. Obviously this can be difficult with chronic pain, but do take your sleep seriously. For example, invest in a good mattress, nice bedding, a good bedtime routine, etc.

*Resveratrol (which is a polyphenol, by the way), famously found in red wine, does have anti-inflammatory properties. However, to get enough resveratrol to be of benefit would require drinking far more wine than will be good for your inflammation or, indeed, the rest of you. So if you’d like resveratrol benefits, consider taking it as a supplement. Superficially it doesn’t seem as much fun as drinking red wine, but we assure you that the results will be much more fun than the inflammation flare-up after drinking.

About the Mediterranean Diet for this…

There are many causes of chronic inflammation, but here are some studies done with some of the most common ones:

- Beneficial effect of Mediterranean diet in systemic lupus erythematosus patients

- How the Mediterranean diet and some of its components modulate inflammatory pathways in arthritis

- The effects of the Mediterranean diet on biomarkers of vascular wall inflammation and plaque vulnerability in subjects with high risk for cardiovascular disease

- Adherence to Mediterranean diet and 10-year incidence of diabetes: correlations with inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers*

*Type 1 diabetes is a congenital autoimmune disorder, as the pancreas goes to war with itself. Type 2 diabetes is different, being a) acquired and b) primarily about insulin resistance, and/but this is related to chronic inflammation regardless. It is also possible to have T1D and go on to develop insulin resistance, and that’s very bad, and/but beyond the scope of today’s newsletter, in which we are focusing on the inflammation aspects.

Some specific foods to eat or avoid…

Eat these:

- Leafy greens

- Cruciferous vegetables

- Tomatoes

- Fruits in general (berries in particular)

- Healthy fats, e.g. olives and olive oil

- Almonds and other nuts

- Dark chocolate (choose high cocoa, low sugar)

Avoid these:

- Processed meats (absolute worst offenders are hot dogs, followed by sausages in general)

- Red meats

- Sugar (includes most fruit juices, but not most actual fruits—the difference with actual fruits is they still contain plenty of fiber, and in many cases, antioxidants/polyphenols that reduce inflammation)

- Dairy products (unless fermented, in which case it seems to be at worst neutral, sometimes even a benefit, in moderation)

- White flour (and white flour products, e.g. white bread, white pasta, etc)

- Processed vegetable oils

See also: 9 Best Drinks To Reduce Inflammation, Says Science

Supplements?

Some supplements that have been found to reduce inflammation include:

(links are to studies showing their efficacy)

Consider Intermittent Fasting

Remember when we talked about the difference between acute and chronic inflammation? It’s fair to wonder “if I reduce my inflammatory response, will I be weakening my immune system?”, and the answer is: generally, no.

Often, as with the above supplements and dietary considerations, reducing inflammation actually results in a better immune response when it’s actually needed! This is because your immune system works better when it hasn’t been working in overdrive constantly.

Here’s another good example: intermittent fasting reduces the number of circulating monocytes (a way of measuring inflammation) in healthy humans—but doesn‘t compromise antimicrobial (e.g. against bacteria and viruses) immune response.

See for yourself: Dietary Intake Regulates the Circulating Inflammatory Monocyte Pool ← the study is about the anti-inflammatory effects of fasting

Share This Post

-

Superfood-Stuffed Squash

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This stuffed squash recipe is packed with so many nutrient-dense ingredients, yet it feels delightfully decadent—a great recipe to have up your sleeve ready for fall.

You will need

- 1 large or two medium butternut squashes, halved lengthways and seeds removed (keep them; they are full of nutrients! You can sprout them, or dry them to use them at your leisure), along with some of the flesh from the central part above where the seeds are, so that there is room for stuffing

- 2 cups low-sodium vegetable stock

- 1 cup wild rice, rinsed

- 1 medium onion, finely chopped

- ½ cup walnuts, roughly chopped

- ½ cup dried

cranberriesgoji berries ← why goji berries? They have even more healthful properties than cranberries, and cranberries are hard to buy without so much added sugar that the ingredients list looks like “cranberries (51%), sugar (39%), vegetable oil (10%)”, whereas when buying goji berries, the ingredients list says “goji berries”, and they do the same culinary job. - ¼ cup pine nuts

- ½ bulb garlic, minced

- 1 tbsp dried thyme or 2 tsp fresh thyme, destalked

- 1 tbsp dried rosemary or 2 tsp fresh rosemary, destalked

- 1 generous handful fresh parsley, chopped

- 1 tbsp chia seeds

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tbsp black pepper, coarse ground

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Extra virgin olive oil, for brushing and frying

- Aged balsamic vinegar, to serve (failing this, make a balsamic vinegar reduction and use that; it should have a thicker texture but still taste acidic and not too sweet; the thickness should come from the higher concentration of grape must and its natural sugars; no need to add sugar)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 400°F / 200°C.

2) Brush the cut sides of the squash with olive oil; sprinkle with a pinch of MSG/salt and a little black pepper (grind it directly over the squash if you are using a grinder; hold the grinder high though so that it distributes evenly—waiters in restaurants aren’t just being dramatic when they do that with pepper or Parmesan or such)

3) Arrange them cut-sides-down on a baking tray lined with baking paper, and roast for at least 30 minutes or until tender.

4) While that is roasting, add the chia seeds to the wild rice, and cook them in the low-sodium vegetable stock, using a rice cooker if available. It should take about the same length of time, but if the rice is done first, set it aside, and if the squash is done first, turn the oven down low to keep it warm.

5) Heat some oil in a sauté pan (not a skillet without high sides; we’re going to need space in a bit), and fry the chopped onion until translucent and soft. We could say “about 5 minutes” but honestly it depends on your pan as well as the heat and other factors.

6) Add the seasonings (herbs, garlic, black pepper, MSG/salt, nooch), and cook for a further 2 minutes, stirring thoroughly to distribute evenly.

7) Add the rice, berries, and nuts, cooking for a further 2 minutes, stirring constantly, ensuring everything is heated evenly.

8) Remove the squash halves from the oven, turn them over, and spoon the mixture we just made into them, filling generously.

9) Drizzle a lashing of the aged balsamic vinegar (or balsamic vinegar reduction), to serve.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Brown Rice vs Wild Rice – Which is Healthier?

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

- Chia: The Tiniest Seeds With The Most Value

- The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

- Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

- 10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

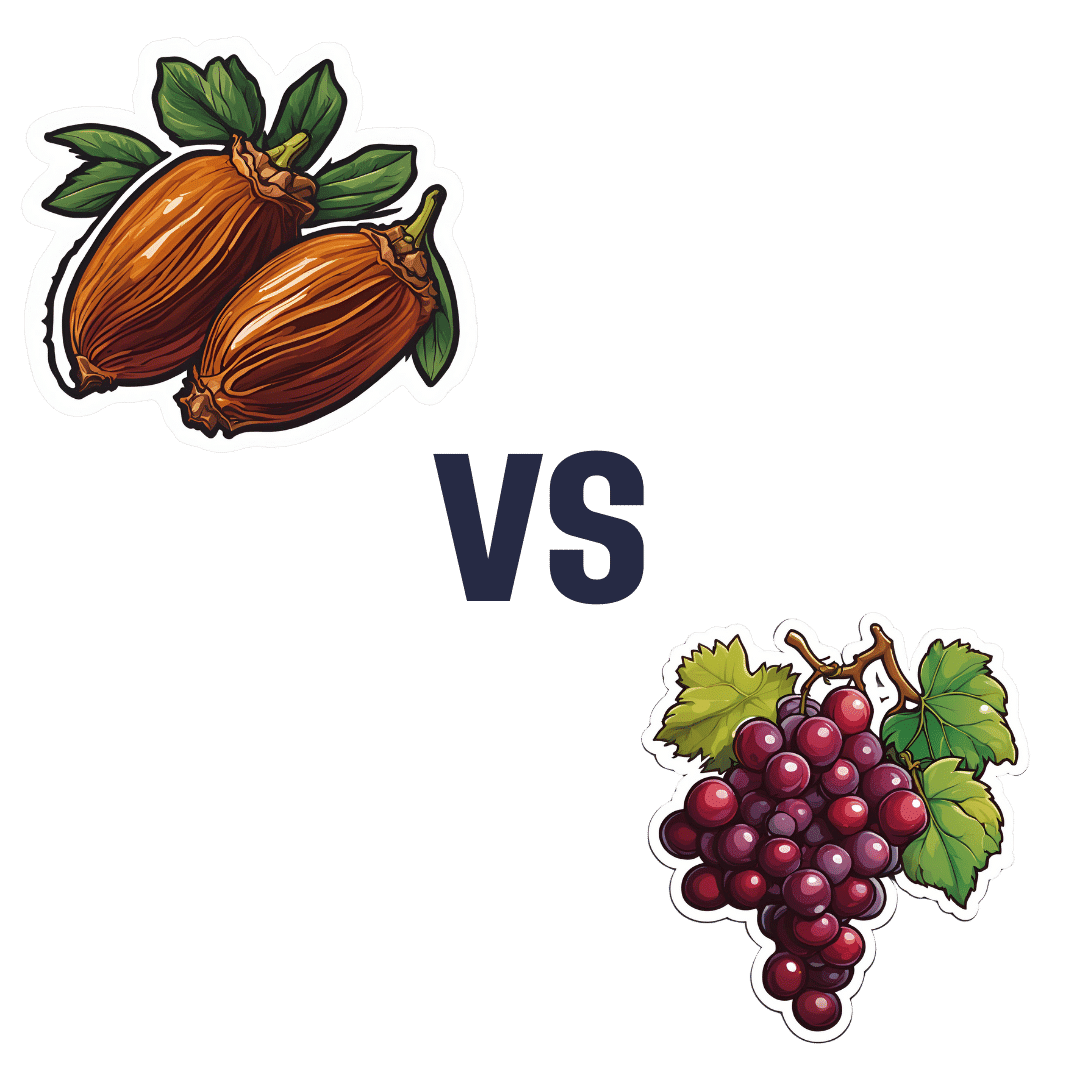

Dates vs Grapes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing dates to grapes, we picked the dates.

Why?

It’s not close:

In terms of macros, dates have 4x the carbs and/but 8x the fiber, making for the lower glycemic index. Also, for what it’s worth, they have nearly 4x the protein, but probably nobody is eating either of these fruits for the protein. In any case, it’s an easy and clear win for dates in the category of macros.

In the category of vitamins, dates have more of vitamins B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, and choline, while grapes have more of vitamins B1, C, E, and K, making for a 6:4 win for dates.

When it comes to minerals, it’s more one-sided: dates have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while grapes have more manganese. An easy win for dates here.

Of course, enjoy either or both (diversity is good), but if you’re looking for nutrient density, dates are where it’s at.

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Can We Drink To Good Health? ← while there are polyphenols such as resveratrol in red wine that per se would boost heart health, there’s so little per glass that you may need 100–1000 glasses per day to get the dosage that provides benefits in mouse studies.

If you’re not a mouse, you might even need more than that!

To this end, many people prefer resveratrol supplementation ← link is to an example product on Amazon, but there are plenty more so feel free to shop around 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Gluconolactone Restores Immune Regulation In Lupus

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Let’s be clear up front: this will not cure lupus.

However, it will interrupt the pathology of lupus in such a way as to, as the title says, restore immune regulation—so that your body stops attacking itself, or at the very least, attacks itself significantly less.

What is gluconolactone anyway?

Gluconolactone (also called glucono-δ-lactone) an oxidized derivative of glucose, when glucose is exposed to oxygen and a certain enzyme (glucose oxidase). It’s used in various food-related fermentation processes, and also helps such foods to have a tangy flavor.

It’s also known as E575, showing that E-numbers need not always be scary 🙂

How does it work?

First, a recap on how lupus works: lupus is an autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks its own tissues, causing inflammation and organ damage (to oversimplify it in very few words).

Next, how lupus is currently treated: mostly with immunosuppressant drugs, which reduce symptoms but have significant side effects, not least of all the fact that your immune system will be suppressed, leaving you vulnerable to infections, cancer, aging, and the like. So, there’s really a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” aspect here (because untreated lupus will run your immune system into the ground with its chronic inflammation, which will also leave you vulnerable to the aforementioned things).

See also: How to Prevent (or Reduce) Inflammation

Now, how gluconolactone works: it increases the number of regulatory T-cells (also called “Tregs” by scientists who don’t want to have to say/write “regulatory T-cells” many times per day), which are the ones that tell the rest of your immune system what not to attack. It also inhibits pro-inflammatory T-helper-cells that are otherwise involved in autoimmune dysfunction.

Where is the science for this?

It’s a shiny new paper that covers three angles:

- In lupus-suffering mouse in vivo studies, it improved Treg function and reduced inflammatory skin rashes

- In human cell culture in vitro studies (with cell cultures from human lupus patients), it bolstered Treg count and improved immune regulation

- In human patient in vivo studies, a gluconolactone cream controlled skin inflammation and improved the clinical and histologic appearance of the skin lesions within 2 weeks

❝These results suggest that gluconolactone could be a targeted treatment option with fewer side effects for autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

Gluconolactone acts like a ‘power food’ for regulatory T cells—a real win-win situation for immune regulation❞

~ Dr. Antonios Kolios

You can find the paper itself here:

Where can I get gluconolactone?

At the moment, this is still in the clinical trials phase, so it’s not something you can get a prescription for yet, alas.

But definitely keep an eye out for it!

We would hypothesize that eating foods fermented with E575 (it’s sometimes used in feta cheese, hence today’s featured image, and it’s also often used as a pickling agent) may well help, but that’s just our hypothesis as it isn’t what was tested in the above studies.

Want to learn more?

In the meantime, if you’d like to learn more about lupus, we recommend this very comprehensive book:

*The “et al.” are: Jemima Albayda, MD; Divya Angra, MD; Alan N. Baer, MD; Sasha Bernatsky, MD, PhD; George Bertsias, MD, PhD; Ashira D. Blazer, MD; Ian Bruce, MD; Jill Buyon, MD; Yashaar Chaichian, MD; Maria Chou, MD; Sharon Christie, Esq; Angelique N. Collamer, MD; Ashté Collins, MD; Caitlin O. Cruz, MD; Mark M. Cruz, MD; Dana DiRenzo, MD; Jess D. Edison, MD; Titilola Falasinnu, PhD; Andrea Fava, MD; Cheri Frey, MD; Neda F. Gould, PhD; Nishant Gupta, MD; Sarthak Gupta, MD; Sarfaraz Hasni, MD; David Hunt, MD; Mariana J. Kaplan, MD; Alfred Kim, MD; Deborah Lyu Kim, DO; Rukmini Konatalapalli, MD; Fotios Koumpouras, MD; Vasileios C. Kyttaris, MD; Jerik Leung, MPH; Hector A. Medina, MD; Timothy Niewold, MD; Julie Nusbaum, MD; Ginette Okoye, MD; Sarah L. Patterson, MD; Ziv Paz, MD; Darryn Potosky, MD; Rachel C. Robbins, MD; Neha S. Shah, MD; Matthew A. Sherman, MD; Yevgeniy Sheyn, MD; Julia F. Simard, ScD; Jonathan Solomon, MD; Rodger Stitt, MD; George Stojan, MD; Sangeeta Sule, MD; Barbara Taylor, CPPM, CRHC; George Tsokos, MD; Ian Ward, MD; Emma Weeding, MD; Arthur Weinstein, MD; Sean A. Whelton, MD

The reason we mention this is to render it clear that this isn’t one man’s opinions (as happens with many books about certain topics), but rather, a panel of that many doctors all agreeing that this is correct and good, evidence-based, up-to-date (as of the publication of this latest revised edition) information.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Pomegranate vs Cranberries – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pomegranate to cranberries, we picked the pomegranate.

Why?

Starting with the macros: pomegranate has nearly 4x the protein (actually quite a lot for a fruit, but this is not too surprising—it’s because we are eating the seeds!), and slightly more carbs and fiber. Their glycemic indices are comparable, both being low GI foods. While both of these fruits have excellent macro profiles, we say the pomegranate is slightly better, because of the protein, and when it comes to the carbs and fiber, since they balance each other out, we’ll go with the option that’s more nutritionally dense. We like foods that add more nutrients!

In the category of vitamins, pomegranate is higher in vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, K, and choline, while cranberry is higher in vitamins A, C, and E. Both are very respectable profiles, but pomegranate wins on strength of numbers (and also some higher margins of difference).

When it comes to minerals, it is not close; pomegranate is higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while cranberry is higher in manganese. An easy win for pomegranate here.

Both of these fruits have additional “special” properties, though it’s worth noting that:

- pomegranate’s bonus properties, which are too many to list here, but we link to an article below, are mostly in its peel (so dry it, and grind it into a powder supplement, that can be worked into foods, or used like an instant fruit tea, just without the sugar)

- cranberries’ bonus properties (including: famously very good at reducing UTI risk) come with some warnings, including that they may increase the risk of kidney stones if you are prone to such, and also that cranberries have anti-clotting effects, which are great for heart health but can be a risk of you’re on blood thinners or have a bleeding disorder.

You can read about both of these fruits’ special properties in more detail below:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

- Pomegranate’s Health Gifts Are Mostly In Its Peel

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: