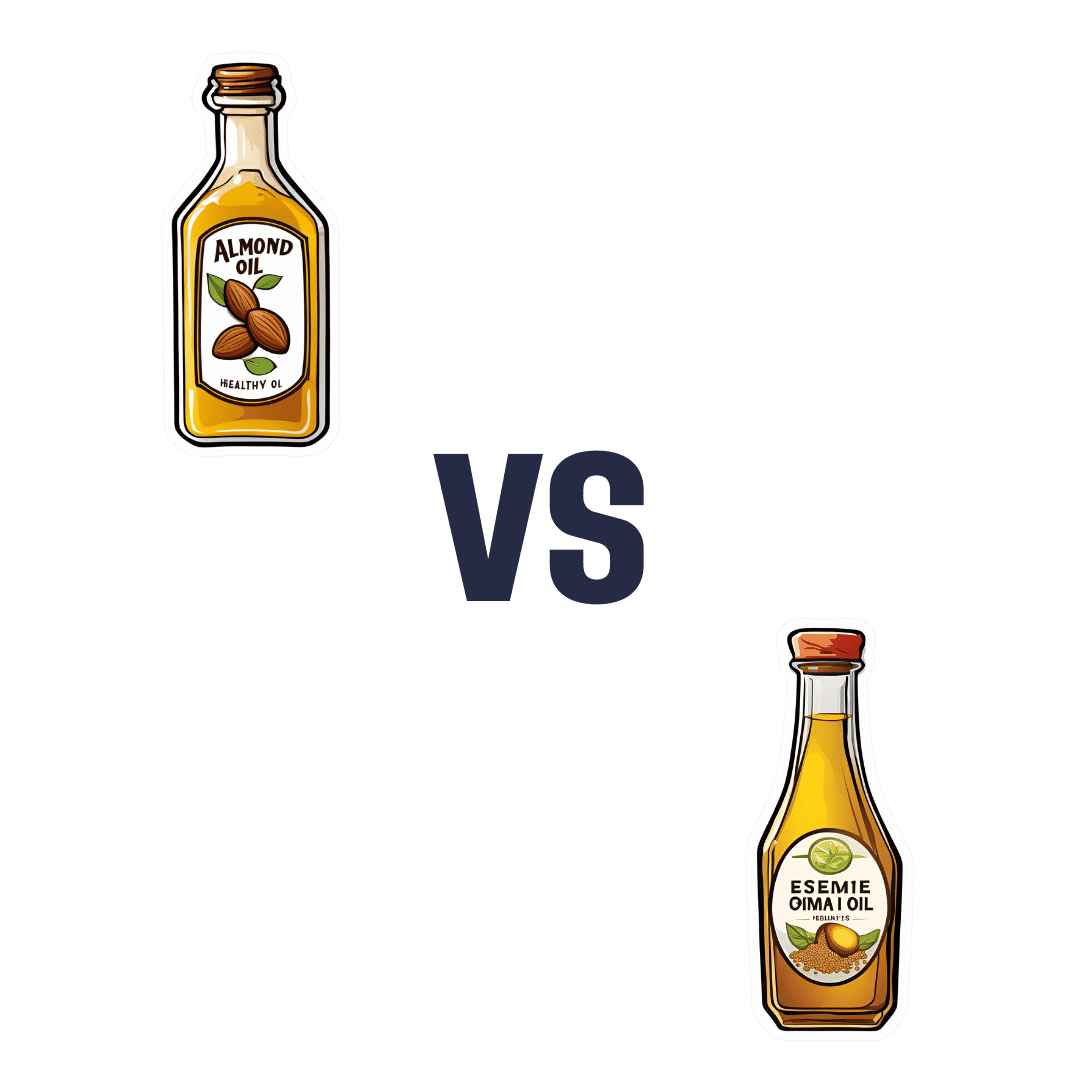

Sesame Oil vs Almond Oil – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing sesame oil to almond oil, we picked the almond.

Why?

We were curious about this one! Were you, or were you confident? You see, almonds tend to blow away all the other nuts with their nutritional density, but they’re far from the oiliest of nuts, and their greatest strengths include their big dose of protein and fiber (which don’t make it into the oil), vitamins (most of which don’t make it into the oil) and minerals (which don’t make it into the oil). So, a lot will come down to the fat profile!

On which note, looking at the macros first, it’s 100% fat in both cases, but sesame oil has more saturated fat and polyunsaturated fat, while almond oil has more monounsaturated fat. Since the mono- and poly-unsaturated fats are both healthy and each oil has more of one or the other, the deciding factor here is which has the least saturated fat—and that’s the almond oil, which has close to half the saturated fat of sesame oil. As an aside, neither of them are a source of omega-3 fatty acids.

In terms of vitamins, there’s not a lot to say here, but “not a lot” is not nothing: sesame oil has nearly 2x the vitamin K, while almond oil has 28x the vitamin E*, and 2x the choline. So, another win for almond oil.

*which is worth noting, not least of all because seeds are more widely associated with vitamin E in popular culture, but it’s the almond oil that provide much more here. Not to get too distracted into looking at the values of the actual seeds and nuts, almonds themselves do have over 102x the vitamin E compared to sesame seeds.

Now, back to the oils:

In the category of minerals, there actually is nothing to say here, except you can’t get more than the barest trace of any mineral from either of these two oils. So it’s a tie on this one.

Adding up the categories makes for a clear win for almond oil!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Avocado Oil vs Olive Oil – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mythbusting The Mask Debate

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mythbusting The Mask Debate

We asked you for your mask policy this respiratory virus season, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- A little under half of you said you will be masking when practical in indoor public places

- A little over a fifth of you said you will mask only if you have respiratory virus symptoms

- A little under a fifth of you said that you will not mask, because you don’t think it helps

- A much smaller minority of you (7%) said you will go with whatever people around you are doing

- An equally small minority of you said that you will not mask, because you’re not concerned about infections

So, what does the science say?

Wearing a mask reduces the transmission of respiratory viruses: True or False?

True…with limitations. The limitations include:

- The type of mask

- A homemade polyester single-sheet is not the same as an N95 respirator, for instance

- How well it is fitted

- It needs to be a physical barrier, so a loose-fitting “going through the motions” fit won’t help

- The condition of the mask

- And if applicable, the replaceable filter in the mask

- What exactly it has to stop

- What kind of virus, what kind of viral load, what kind of environment, is someone coughing/sneezing, etc

More details on these things can be found in the link at the end of today’s main feature, as it’s more than we could fit here!

Note: We’re talking about respiratory viruses in general in this main feature, but most extant up-to-date research is on COVID, so that’s going to appear quite a lot. Remember though, even COVID is not one beast, but many different variants, each with their own properties.

Nevertheless, the scientific consensus is “it does help, but is not a magical amulet”:

- 2021: Effectiveness of Face Masks in Reducing the Spread of COVID-19: A Model-Based Analysis

- 2022: Why Masks are Important during COVID‐19 Pandemic

- 2023: The mitigating effect of masks on the spread of COVID-19

Wearing a mask is actually unhygienic: True or False?

False, assuming your mask is clean when you put it on.

This (the fear of breathing more of one’s own germs in a cyclic fashion) was a point raised by some of those who expressed mask-unfavorable views in response to our poll.

There have been studies testing this, and they mostly say the same thing, “if it’s clean when you put it on, great, if not, then well yes, that can be a problem”:

❝A longer mask usage significantly increased the fungal colony numbers but not the bacterial colony numbers.

Although most identified microbes were non-pathogenic in humans; Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Cladosporium, we found several pathogenic microbes; Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Aspergillus, and Microsporum.

We also found no associations of mask-attached microbes with the transportation methods or gargling.

We propose that immunocompromised people should avoid repeated use of masks to prevent microbial infection.❞

Source: Bacterial and fungal isolation from face masks under the COVID-19 pandemic

Wearing a mask can mean we don’t get enough oxygen: True or False?

False, for any masks made-for-purpose (i.e., are by default “breathable”), under normal conditions:

- COVID‐19 pandemic: do surgical masks impact respiratory nasal functions?

- Performance Comparison of Single and Double Masks: Filtration Efficiencies, Breathing Resistance and CO2 Content

However, wearing a mask while engaging in strenuous best-effort cardiovascular exercise, will reduce VO₂max. To be clear, you will still have more than enough oxygen to function; it’s not considered a health hazard. However, it will reduce peak athletic performance:

…so if you are worrying about whether the mask will impede you breathing, ask yourself: am I engaging in an activity that requires my peak athletic performance?

Also: don’t let it get soaked with water, because…

Writer’s anecdote as an additional caveat: in the earliest days of the COVID pandemic, I had a simple cloth mask on, the one-piece polyester kind that we later learned quite useless. The fit wasn’t perfect either, but one day I was caught in heavy rain (I had left it on while going from one store to another while shopping), and suddenly, it fitted perfectly, as being soaked through caused it to cling beautifully to my face.

However, I was now effectively being waterboarded. I will say, it was not pleasant, but also I did not die. I did buy a new mask in the next store, though.

tl;dr = an exception to “no it won’t impede your breathing” is that a mask may indeed impede your breathing if it is made of cloth and literally soaked with water; that is how waterboarding works!

Want up-to-date information?

Most of the studies we cited today were from 2022 or 2023, but you can get up-to-date information and guidance from the World Health Organization, who really do not have any agenda besides actual world health, here:

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Masks | Frequently Asked Questions

At the time of writing this newsletter, the above information was last updated yesterday.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Kitchen Doctor

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

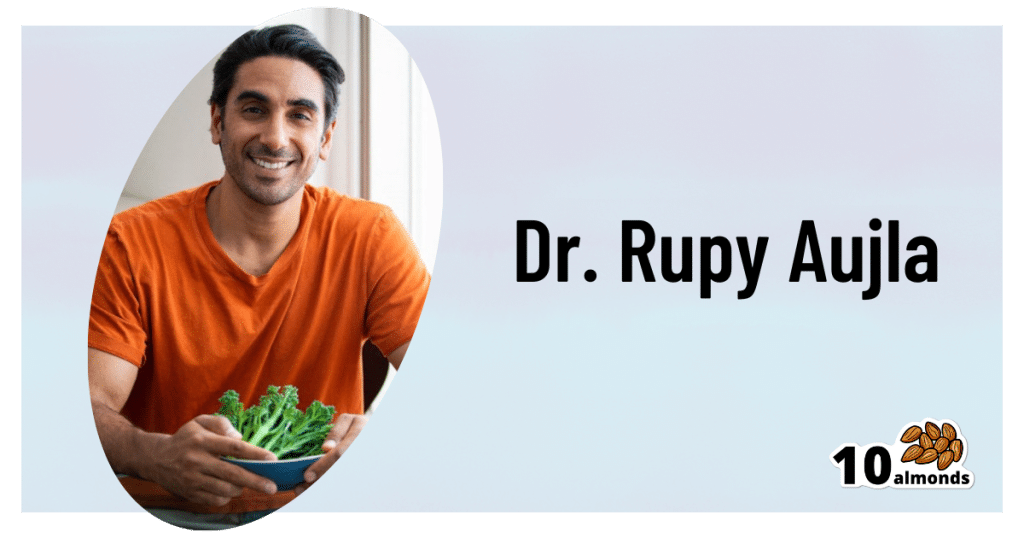

Dr. Rupy Aujla: The Kitchen Doctor

This is Dr. Rupy Aujla, and he’s a medical doctor. He didn’t set out to become a “health influencer”.

But then, a significant heart condition changed his life. Having a stronger motivation to learn more about nutritional medicine, he did a deep dive into the scientific literature, because that’s what you do when your life is on the line, especially if you’re a doctor!

Using what he learned, he was able to reverse his condition using a food and lifestyle approach. Now, he devotes himself to sharing what he learned—and what he continues to learn as he goes along.

One important thing he learned because of what happened to him, was that he hadn’t been paying enough attention to what his body was trying to tell him.

He wants us to know about interoception—which isn’t a Chris Nolan movie. Rather, interoception is the sense of what is going on inside one’s own body.

The counterpart of this is exteroception: our ability to perceive the outside world by means of our various senses.

Interoception is still using the senses, but is sensing internal body sensations. Effectively, the brain interprets and integrates what happens in our organs.

When interoception goes wrong, researchers found, it can lead to a greater likelihood of mental health problems. Having an anxiety disorder, depression, mood disorder, or an eating disorder often comes with difficulties in sensing what is going on inside the body.

Improving our awareness of body cues

Those same researchers suggested therapies and strategies aimed at improving awareness of mind-body connections. For example, mindfulness-based stress reduction, yoga, meditation and movement-based treatments. They could improve awareness of body cues by attending to sensations of breathing, cognitions and other body states.

But where Dr. Aujla puts his focus is “the heart of the home”, the kitchen.

The pleasure of food

❝Eating is not simply ingesting a mixture of nutrients. Otherwise, we would all be eating astronaut food. But food is not only a tool for health. It’s also an important pleasure in life, allowing us to connect to others, the present moment and nature.❞

Dr. Rupy Aujla

Dr. Aujla wants to help shift any idea of a separation between health and pleasure, because he believes in food as a positive route to well-being, joy and health. For him, it starts with self-awareness and acceptance of the sensory pleasures of eating and nourishing our bodies, instead of focusing externally on avoiding perceived temptations.

Most importantly:

We can use the pleasure of food as an ally to healthy eating.

Instead of spending our time and energy fighting the urge to eat unhealthy things that may present a “quick fix” to some cravings but aren’t what our body actually wants, needs, Dr. Aujla advises us to pay just a little more attention, to make sure the body’s real needs are met.

His top tips for such are:

- Create an enjoyable relaxing eating environment

To help cultivate positive emotions around food and signal to the nervous system a shift to food-processing time. Try setting the table with nothing else on it beyond what’s relevant to the dinner, putting away distractions, using your favorite plates, tablecloth, etc.

- Take 3 deep abdominal breaths before eating

To help you relax and ground yourself in the present moment, which in turn is to prepare your digestive system to receive and digest food.

- Pay attention to the way you sit

Take some time to sit comfortably with your feet grounded on the floor, not slouching, to give your stomach space to digest the food.

- Appreciate what it took to bring this food to your plate

Who was involved in the growing process and production, the weather and soil it took to grow the food, and where in the world it came from.

- Enjoy the sensations

When you’re cooking, serving, and eating your food, be attentive to color, texture, aroma and even sound. Taste the individual ingredients and seasonings along the way, when safe and convenient to do so.

- Journal

If you like journaling, you can try adding a mindful eating section to that. Ask questions such as: “how did I feel before, during, and after the meal?”

In closing…

Remember that this is a process, not only on an individual level but as a society too.

Oftentimes it’s hard to eat healthily… We can be given to wonder even “what is healthy, after all?”, and we can be limited by what is available, what is affordable, and what we have time to prepare.

But if we make a conscious commitment to make the best choices we reasonably can as we go along, then small changes can soon add up.

Interested in what kind of recipes Dr. Aujla goes for?

Share This Post

-

Spermidine For Longevity

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝How much evidence is there behind the longevity-related benefit related to spermidine, and more specifically, does it cause autophagy?❞

A short and simple answer to the latter question: yes, it does:

Spermidine: a physiological autophagy inducer acting as an anti-aging vitamin in humans?

For anyone wondering what autophagy is: it’s when old cells are broken down and consumed by the body to make new ones. Doing this earlier rather than later means that the genetic material is not yet so degraded when it is copied, and so the resultant new cell(s) will be “younger” than if the previous cell(s) had been broken down and recycled when older.

Indeed, we have written previously about senolytic supplements such as fisetin, which specialize in killing senescent (aging) cells earlier:

Fisetin: The Anti-Aging Assassin

As for spermidine and longevity, because of its autophagy-inducing properties, it’s considered a caloric restriction mimetic, that is to say, it has the same effect on a cellular level as caloric restriction. And yes, while it’s not an approach we regularly recommend here (usually preferring intermittent fasting as a CR-mimetic), caloric restriction is a way to fight aging:

Is Cutting Calories The Key To Healthy Long Life?

As for how spermidine achieves similarly:

Spermidine delays aging in humans

However! Both of the scientific papers on spermidine use in humans that we’ve cited so far today have conflict of interests statements made with regard to the funding of the studies, which means there could be some publication bias.

To that end, let’s look at a less glamorous study (e.g. no “in humans” in the title because, like most longevity studies, it’s with non-human animals with naturally short lifespans such as mice and rats), like this one that finds it to be both cardioprotective and neuroprotective and having many anti-aging benefits mediated by inducing autophagy:

A review on polyamines as promising next-generation neuroprotective and anti-aging therapy

(the polyamines in question are spermidine and putrescine, which latter is a similar polyamine)

Lastly, let’s answer a few likely related questions, so that you don’t have to Google them:

Does spermidine come from sperm?

Amongst other places (including some foods, which we’ll come to in a moment), yes, spermidine is normally found in semen (in fact, it’s partly responsible for the normal smell, though other factors influence the overall scent, such as diet, hormones, and other lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol use etc) and that is how/where it was first identified.

Does that mean that consuming semen is good for longevity?

Aside from the health benefits of a healthy sex life… No, not really. Semen does contain spermidine (as discussed) as well as some important minerals, but you’d need to consume approximately 1 cup of semen to get the equivalent spermidine you’d get from 1 tbsp of edamame (young soy) beans.

Unless your lifestyle is rather more exciting than this writer’s, it’s a lot easier to get 1 tbsp of edamame beans than 1 cup of semen.

Here are how some top foods stack up, by the way—we admittedly cherry-picked from the near top of the list, but wheatgerm is an even better source, with cheddar cheese and mushrooms (it was shiitake in the study) coming after soy:

Frontiers in Nutrition | Polyamines in Food

Alternatively, if you prefer to just take it in supplement form, here’s an example product on Amazon, giving 5mg per capsule (which is almost as much as the 1 cup of semen or 1 tbsp of edamame that we mentioned earlier).

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Beat The Heat, With Fat

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Surviving Summer

Summer is upon us, for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere anyway, and given that nowadays each year tends to be hotter than the one before, on average, it pays to be prepared.

We’ve talked about dealing with the heat before:

Sun, Sea, And Sudden Killers To Avoid

All the above advice stands this summer too, but today we’re going to speak a little extra on not having a “default body”.

For much of medical literature and common health advice, the default body is that of a slim and/or athletic white cis man aged 25–35 with no disabilities.

When it comes to “women’s health”, this is often confined to “the bikini zone” and everything else is commonly treated based on research conducted with men.

Today we’ll be looking at a particular challenge for a wide variety of people, when it comes to heat…

Beating the heat, with fat

If you are fat, and/or have a bit of a tummy, and/or have breasts, this one’s for you.

Fat acts as an insulator, which naturally does no favors in hot weather. Carrying the weight around is also extra exercise, which also becomes a problem in hot weather. Fat people usually sweat more than thin people do, as a result.

Sweat is great for cooling down the body, because it takes heat with it when it evaporates off. However, that only works if it can evaporate off, and it can’t evaporate off if it’s trapped in a skin fold / fat roll.

If you’re fat, you may have plenty of those; if you have a bit of a tummy (if you’re not fat generally, this might be a leftover from pregnancy, or weight loss, or something else; how it got there doesn’t matter for our purposes today), you’ll have at least one under it, and if you have breasts, unless they’re quite small, you’ll have one under each breast, and potentially your cleavage may become an issue too.

Note: if you are perhaps a man who has fat in the place where breasts go, then medically this goes for you too, except that there’s not a societal expectation that you wear bra. Use today’s information as you see fit.

Sweat-wicking hacks

We don’t want sweat to stay in those folds—both because then it’s not doing its cooling-down job, and also, because it can cause a rash, and even yeast infections and/or bacterial infections.

So, we want there to be some barrier there. You could use something like vaseline or baby powder, as to prevent chafing, but fat better (more effective, and less messy) is to have some kind of cloth there that can wick the sweat away.

There are made-for-purpose curved cotton bands that exist, called “tummy liners”; here’s an example product on Amazon, or you could make your own if you’re so inclined. They’re breathable, absorbent, and reduce friction too, making everything a lot more comfortable.

And for breasts? Same deal, there are made-for-purpose cotton bra-liners that exist; here’s an example product on Amazon, or again, you could make your own if you feel so inclined. The important part is that it makes things so much comfortable, because let’s face it: wearing a bra in the summer is not comfortable.

So with these, it can become more comfortable (and the cotton liners are flat, so they’re not visible if one’s wearing a t-shirt or similar-coverage garment). You could go braless, of course, but then you’re back to having sweaty folds, so if you’re doing something other than swimming or lying on your back, you might want something there.

Different hydration rules

“People should drink this much per day” and guess what, those guidelines were based on, drumroll please, not fat people.

Sweating more means needing to hydrate more, and even without breaking a sweat, having a larger body than average (be it muscle, fat, or both) means having more body to hydrate. That’s simple math.

So instead, a good general guideline is half an ounce of water per your weight in pounds, per day:

How much water do I need each day?

Another good general guideline is to simply drink “little and often”, that is to say, always have a (hydrating!) drink on the go.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Discipline is Destiny – by Ryan Holiday

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed another of Holiday’s books, The Daily Stoic, and here is another excellent work from the same author.

We’re not a philosophy newsletter, but there are some things that make a big difference to physical and mental health, the habits we build, and the path we take in life for better or for worse.

Self-discipline is one of those things. A lot of the time, we know what we need to do, but knowing isn’t the problem. We need to actually do it! This applies to diet, exercise, sleep, and more.

Holiday gives us, in a casual easy-reading style, timeless principles to lock in strong discipline and good habits for life.

The book’s many small chapters, by the way, are excellent for reading a chapter-per-day as a healthy dose of motivation each morning, if you’re so inclined.

Bottom line: if you’ve noticed that one of the biggest barriers between you and your goals is actually doing the necessary things in a disciplined fashion, then this book will help you become more efficient, and actually get there.

Click here to check out Discipline is Destiny, and upgrade yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Improve Your Insulin Sensitivity!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written before about blood sugar management, for example:

10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars ← this one really is the most solid foundation possible; if you do nothing else, do these 10 things!

And as for why we care:

Good (Or Bad) Health Starts With Your Blood

…because the same things that cause type 2 diabetes, go on to cause many other woes, with particularly strong comorbidities in the case of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, as well as heart disease of various kinds, and a long long laundry list of immune dysfunctions / inflammatory disorders in general.

In short, if you can’t keep your blood sugars even, the rest of your health will fall like so many dominoes.

Getting a baseline

Are you counting steps? Counting calories? Monitoring your sleep? Heart rate zones? These all have their merits:

- Steps: One More Resource Against Osteoporosis!

- Calories: Is Cutting Calories The Key To Healthy Long Life?

- Sleep: A Head-To-Head Of Google and Apple’s Top Apps For Getting Your Head Down

- Heart Rate Zones: Heart Rate Zones, Oxalates, & More

But something far fewer people do unless they have diabetes or are very enthusiastic about personal health, is to track blood sugars:

Here’s how: Track Your Blood Sugars For Better Personalized Health

And for understanding some things to watch out for when using a continuous glucose monitor:

Continuous Glucose Monitors Without Diabetes: Pros & Cons

Writer’s anecdote: I decided to give one a try for a few months, and so far it has been informative, albeit unexciting. It seems that with my diet (mostly whole-foods plant based, though I do have a wholegrain wheat product about twice per week (usually: flatbread once, pasta once) which is… Well, we could argue it’s whole-food plant based, but let’s be honest, it’s a little processed), my blood sugars don’t really have spikes at all; the graph looks more like gently rolling low hills (which is good). However! Even so, by experimenting with it, I can see for myself what differences different foods/interventions make to my blood sugars, which is helpful, and it also improves my motivation for intermittent fasting. It also means that if I think “hmm, my energy levels are feeling low; I need a snack” I can touch my phone to my arm and find out if that is really the reason (so far, it hasn’t been). I expect that as I monitor my blood sugars continuously and look at the data frequently, I’ll start to get a much more intuitive feel for my own blood sugars, in much the same way I can generally intuit my hormone levels correctly after years of taking-and-testing.

So much for blood sugars. Now, what about insulin?

Step Zero

If taking care of blood sugars is step one, then taking care of insulin is step zero.

Often’s it’s viewed the other way around: we try to keep our blood sugars balanced, to reduce the need for our bodies to produce so much insulin that it gets worn out. And that’s good and fine, but…

To quote what we wrote when reviewing “Why We Get Sick” last month:

❝Dr. Bikman makes the case that while indeed hyper- or hypoglycemia bring their problems, mostly these are symptoms rather than causes, and the real culprit is insulin resistance, and this is important for two main reasons:

- Insulin resistance occurs well before the other symptoms set in (which means: it is the thing that truly needs to be nipped in the bud; if your fasting blood sugars are rising, then you missed “nipping it in the bud” likely by a decade or more)

- Insulin resistance causes more problems than “mere” hyperglycemia (the most commonly-known result of insulin resistance) does, so again, it really needs to be considered separately from blood sugar management.

This latter, Dr. Bikman goes into in great detail, linking insulin resistance (even if blood sugar levels are normal) to all manner of diseases (hence the title).

You may be wondering: how can blood sugar levels be normal, if we have insulin resistance?

And the answer is that for as long as it is still able, your pancreas will just faithfully crank out more and more insulin to deal with the blood sugar levels that would otherwise be steadily rising. Since people measure blood sugar levels much more regularly than anyone checks for actual insulin levels, this means that one can be insulin resistant for years without knowing it, until finally the pancreas is no longer able to keep up with the demand—then that’s when people finally notice.❞

You can read the full book review here:

Now, testing for insulin is not so quick, easy, or accessible as testing for glucose, but it can be worthwhile to order such a test—because, as discussed, your insulin levels could be high even while your blood sugars are still normal, and it won’t be until the pancreas finally reaches breaking point that your blood sugars show it.

So, knowing your insulin levels can help you intervene before your pancreas reaches that breaking point.

We can’t advise on local services available for ordering blood tests (because they will vary depending on location), but a simple Google search should suffice to show what’s available in your region.

Once you know your insulin levels (or even if you don’t, but simply take the principled position that improving insulin sensitivity will be good regardless), you can set about managing them.

Insulin sensitivity is important, because the better it is (higher insulin sensitivity), the less insulin the pancreas has to make to tidy up the same amount of glucose into places that are good for it to go—which is good. In contrast, the worse it is (higher insulin resistance), the more insulin the pancreas has to make to do the same blood sugar management. Which is bad.

What to do about it

We imagine you will already be eating in a way that is conducive to avoiding or reversing type 2 diabetes, but for anyone who wants a refresher,

See: How To Prevent And Reverse Type 2 Diabetes

…which yes, as well as meaning eating/avoiding certain foods, does recommend intermittent fasting. For anyone who wants a primer on that,

See: Intermittent Fasting: Methods & Benefits

There are also drugs you may want to consider:

Metformin Without Diabetes, For Weight-Loss & More

And “nutraceuticals” that sound like drugs, for example:

Glutathione’s Benefits: The Usual And The Unique ← the good news is, it’s found in several common foods

You may have heard the hype about “nature’s Ozempic”, and berberine isn’t exactly that (works in mostly different ways), but its benefits do include improving insulin sensitivity:

Berberine For Metabolic Health

Lastly, while eating for blood sugar management is all well and good, do be aware that some things affect insulin levels without increased blood sugar levels. So even if you’re using a CGM, you may go blissfully unaware of an insulin spike, because there was no glucose spike on the graph—and in contrast, there could even be a dip in blood sugar levels, if you consumed something that increased insulin levels without providing glucose at the same time, making you think “I should have some carbs”, which visually on the graph would even out your blood sugars, but invisibly, would worsen the already-extant insulin spike.

Read more about this: Strange Things Happening In The Islets Of Langerhans: When Carbs, Proteins, & Fats Switch Metabolic Roles

Now, since you probably can’t test your insulin at a moment’s notice, the way to watch out for this is “hmm, I ate some protein/fats (delete as applicable) without carbs and my blood sugars dipped; I know what’s going on here”.

Want to know more?

We heartily recommend the “Why We Get Sick” book we linked above, as this focuses on insulin resistance/sensitivity itself!

However, a very good general primer on blood sugar management (and thus, by extension, at least moderately good insulin management), is:

Glucose Revolution: The Life-Changing Power of Balancing Your Blood Sugar – by Jessie Inchauspé

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: