Is Cutting Calories The Key To Healthy Long Life?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Caloric Restriction with Optimal Nutrition

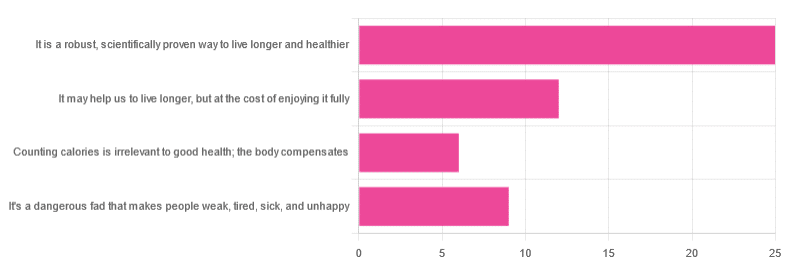

Yesterday, we asked you “What is your opinion of caloric restriction as a health practice?” and got the above-depicted, below-described spread of responses:

- 48% said “It is a robust, scientifically proven way to live longer and healthier”

- 23% said “It may help us to live longer, but at the cost of enjoying it fully”

- 17% said “It’s a dangerous fad that makes people weak, tired, sick, and unhealthy”

- 12% said “Counting calories is irrelevant to good health; the body compensates”

So… What does the science say?

A note on terms, first

“Caloric restriction” (henceforth: CR), as a term, sees scientific use to mean anything from a 25% reduction to a 50% reduction, compared to metabolic base rate.

This can also be expressed the other way around, “dropping to 60% of the metabolic base rate” (i.e., a 40% reduction).

Here we don’t have the space to go into much depth, so our policy will be: if research papers consider it CR, then so will we.

A quick spoiler, first

The above statements about CR are all to at least some degree True in one way or another.

However, there are very important distinctions, so let’s press on…

CR is a robust, scientifically proven way to live longer and healthier: True or False?

True! This has been well-studied and well-documented. There’s more science for this than we could possibly list here, but here’s a good starting point:

❝Calorie restriction (CR), a nutritional intervention of reduced energy intake but with adequate nutrition, has been shown to extend healthspan and lifespan in rodent and primate models.

Accumulating data from observational and randomized clinical trials indicate that CR in humans results in some of the same metabolic and molecular adaptations that have been shown to improve health and retard the accumulation of molecular damage in animal models of longevity.

In particular, moderate CR in humans ameliorates multiple metabolic and hormonal factors that are implicated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, the leading causes of morbidity, disability and mortality❞

Source: Ageing Research Reviews | Calorie restriction in humans: an update

See also: Caloric restriction in humans reveals immunometabolic regulators of health span

We could devote a whole article (or a whole book, really) to this, but the super-short version is that it lowers the metabolic “tax” on the body and allows the body to function better for longer.

CR may help us to live longer, but at the cost of enjoying it fully: True or False?

True or False, contingently, depending on what’s important to you. And that depends on psychology as much as physiology, but it’s worth noting that there is often a selection bias in the research papers; people ill-suited to CR drop out of the studies and are not counted in the final data.

Also, relevant for a lot of our readers, most (human-based) studies recruit people over 18 and under 60. So while it is reasonable to assume the same benefits will be carried over that age, there is not nearly as much data for it.

Studies into CR and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) have been promising, and/but have caveats:

❝In non-obese adults, CR had some positive effects and no negative effects on HRQoL.❞

❝We do not know what degree of CR is needed to achieve improvements in HRQoL, but we do know it requires an extraordinary amount of support.

Therefore, the incentive to offer this intervention to a low-risk, normal or overweight individual is lacking and likely not sustainable in practice.❞

CR a dangerous fad that makes people weak, tired, sick, and unhealthy: True or False?

True if it is undertaken improperly, and/or without sufficient support. Many people will try CR and forget that the idea is to reduce metabolic load while still getting good nutrition, and focus solely on the calorie-counting.

So for example, if a person “saves” their calories for the day to have a night out in a bar where they drink their calories as alcohol, then this is going to be abysmal for their health.

That’s an extreme example, but lesser versions are seen a lot. If you save your calories for a pizza instead of a night of alcoholic drinks, then it’s not quite so woeful, but for example the nutrition-to-calorie ratio of pizza is typically not great. Multiply that by doing it as often as not, and yes, someone’s health is going to be in ruins quite soon.

Counting calories is irrelevant to good health; the body compensates: True or False?

True if by “good health” you mean weight loss—which is rarely, if ever, what we mean by “good health” here at 10almonds (unless we clarify such), but it’s a very common association and indeed, for some people it’s a health goal. You cannot sustainably and healthily lose weight by CR alone, especially if you’re not getting optimal nutrition.

Your body will notice that you are starving, and try to save you by storing as much fat as it can, amongst other measures that will similarly backfire (cortisol running high, energy running low, etc).

For short term weight loss though, yes, it’ll work. At a cost. That we don’t recommend.

❝By itself, decreasing calorie intake will have a limited short-term influence.❞

Source: Reducing Calorie Intake May Not Help You Lose Body Weight

See also…

❝Caloric restriction is a commonly recommended weight-loss method, yet it may result in short-term weight loss and subsequent weight regain, known as “weight cycling”, which has recently been shown to be associated with both poor sleep and worse cardiovascular health❞

Source: Dieting Behavior Characterized by Caloric Restriction

In summary…

Caloric restriction is a well-studied area of health science. We know:

- Practised well, it can extend not only lifespan, but also healthspan

- Practised well, it can improve mood, energy, sexual function, and the other things people fear losing

- Practised badly, it can be ruinous to the health—it is critical to practise caloric restriction with optimal nutrition.

- Practised badly, it can lead to unhealthy weight loss and weight regain

One final note…

If you’ve tried CR and hated it, and you practised it well (e.g., with optimal nutrition), then we recommend just not doing it.

You could also try intermittent fasting instead, for similar potential benefits. If that doesn’t work out either, then don’t do that either!

Sometimes, we’re just weird. It can often be because of a genetic or epigenetic quirk. There are usually workarounds, and/but not everything that’s right for most people will be right for all of us.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Workout Advice For Busy People

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hampton at Hybrid Calisthenics always has very sound advice in his uplifting videos, and this one’s no exception:

Key tips for optimizing workouts without burning out

“We all have the same 24 hours” is a folly when in fact, some of us have more responsibilities and/or other impediments to getting things done (e.g. disabilities).

A quick word on disabilities first: sometimes people are quick to point out Paralympian athletes, and “if they can do it, so can you!” and forget that these people are in the top percentile of the top percentile of the top percentile of human performance. If you wouldn’t disparagingly say “if Simone Biles/Hussein Bolt/Michael Phelps can do it, so can you”, then don’t for Paralympians either 😉

Now, as for Hampton’s advice, he recommends:

Enjoy short, intense workouts:

- You can get effective results in under 30 minutes (or even just a few minutes per day) with compound exercises (e.g., squats, pull-ups).

- Focus on full-body movements also saves time!

- Push closer to failure when possible to maximize efficiency. It’s the last rep where most of the strength gains are made! Same deal with cardiovascular fitness, too. Nevertheless, do take safety into account in both cases, of course.

Time your rest periods:

- Resting for 2–3 minutes between sets ensures optimal recovery.

- Avoid getting distracted during rest by setting a timer to stay focused.

- 10almonds tip: use this time to practice a mindfulness meditation. That will greatly reduce the chance of you becoming distracted.

Remember holistic fitness:

- Fitness isn’t just about exercise; diet, sleep, and stress management are equally important for your fitness as much as for the rest of your health.

- Better sleep and reduced stress will help you exercise more consistently and avoid junk food.

Address burnout:

- If feeling too exhausted to apply these tips, focus on getting better rest and reducing stress first.

- Taking a short break to reset can help in the long run.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- How To Do High Intensity Interval Training (Without Wrecking Your Body)

- How To Rest More Efficiently (Yes, Really)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Laugh Often, To Laugh Longest!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Putting The Abs Into Absurdity

We’ve talked before about the health benefits of a broadly positive outlook on life:

Optimism Seriously Increases Longevity!

…and we’re very serious about it, but that’s about optimistic life views in general, and today we’re about not just keeping good humor in questionable circumstances, but actively finding good humor in the those moments—even when the moments in question might not be generally described as good!

After all, laughter really can be the best medicine, for example:

From the roots

First a quick recap on de-toothing the psychological aspect of threats, no matter how menacing they may be:

Hello, Emotions: Time For Radical Acceptance!

…which we can then take a step further:

What’s The Worst That Could Happen?

Choose your frame

Do you remember when that hacker hacked and publicized the US Federal no-fly list, after already hacking a nationwide cloud-based security camera company, getting access to more than 150,000 companies’ and private individuals’ security cameras, amongst various other cyber crimes, mostly various kinds of fraud and data theft?

Imagine how she (age 21) must have felt, when being indicted. What do you suppose this hacker had to say for itself under such circumstances?

❝congress is investigating now 🙂

but i stay silly :3 ❞

…the latter half of which, usually rendered “but I stay silly” or “but we stay silly” has since entered popular Gen-Z parlance, usually after expressing some negative thing, often in a state of powerlessness.

Which is an important life skill if powerlessness is something that is often likely.

It’s important for many Gen-Zs with negligible life prospects economically; it’s equally important for 60-somethings getting cancer diagnoses (statistically the most likely decade to find out one has cancer, by the way), and many other kinds of people younger, older, and in between.

Because at the end of the day, we all start powerless and we all end powerless.

Learned helplessness (two kinds)

In psychology, “learned helplessness” occurs when a person or creature gives up after learning that all and any attempts to resist a Bad Thing™ fail, perhaps even badly. A lab rat may just shut down and sit there getting electroshocked, for example. A person subjected to abuse may stop trying to improve their situation, and just go with the path of least resistance.

But, there’s another kind, wherein someone in a position of absolute powerlessness not only makes their peace with that, but also, decides that the one thing the outside world can’t control, is how they take it. Like the hacker we mentioned earlier.

Sometimes the gallows humor is even more literal, laughing at one’s own impending death. Not as a matter of bravado, but genuinely seeing the funny side.

But how?

Unfortunately, fortunately

The trick here is to “find a silver lining” that is nowhere near enough to compensate for the bad thing—and it may even be worse! But that’s fine:

“Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to do the dishes before leaving for my vacation. Fortunately, I also forgot to turn the oven off, so the house burning down covered up my messy kitchen”

Writer’s personal less drastic example: today I set my espresso machine to press me an espresso; it doesn’t have an auto-off and I got distracted and it overflowed everywhere; my immediate reaction was “Oh! I have been blessed with an abundance of coffee!”

This kind of silly little thing, on a daily basis, builds a very solid habit for life that allows one to see the funny side in even the most absurd situations, even matters of life and death (can confirm: been there enough times personally—so far so good, still alive to find the remembered absurdity silly).

The point is not to genuinely value the “silver lining”, because half the time it isn’t even one, really, and it is useless to pretend, in seriousness.

But to pretend in silliness? Now we’re onto something, and the real benefit is in the laughs we had along the way.

Because those worst moments? Are probably when we need it the most, so it’s good to get some practice in!

Want more ways to find the funny and make it a life habit?

We reviewed a good book recently:

The Humor Habit: Rewire Your Brain To Stress Less, Laugh More, And Achieve More’er – by Paul Osincup

Stay silly!

Share This Post

-

A Surprisingly Powerful Tool: Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing (EMDR)

What skeletons are in your closet? As life goes on, most of accumulate bad experiences as well as good ones, to a greater or lesser degree. From clear cases of classic PTSD, to the widely underexamined many-headed beast that is C-PTSD*, our past does affect our present. Is there, then, any chance for our future being different?

*PTSD is typically associated with military veterans, for example, or sexual assault survivors. There was a clear, indisputable, Bad Thing™ that was experienced, and it left a psychological scar. When something happens to remind us of that—say, there are fireworks, or somebody touches us a certain way—it’ll trigger an immediate strong response of some kind.

These days the word “triggered” has been popularly misappropriated to mean any adverse emotional reaction, often to something trivial.

But, not all trauma is so clear. If PTSD refers to the result of that one time you were smashed with a sledgehammer, C-PTSD (Complex PTSD) refers to the result of having been hit with a rolled-up newspaper every few days for fifteen years, say.

This might have been…

- childhood emotional neglect

- a parent with a hair-trigger temper

- bullying at school

- extended financial hardship as a young adult

- “just” being told or shown all too often that your best was never good enough

- the persistent threat (real or imagined) of doom of some kind

- the often-reinforced idea that you might lose everything at any moment

If you’re reading this list and thinking “that’s just life though”, you might be in the estimated 1 in 5 people with (often undiagnosed) C-PTSD.

For more on C-PTSD, see our previous main feature:

So, what does eye movement have to do with this?

Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing (EMDR) is a therapeutic technique whereby a traumatic experience (however small or large; it could be the memory of that one time you said something very regrettable, or it could be some horror we couldn’t describe here) is recalled, and then “detoothed” by doing a bit of neurological jiggery-pokery.

How the neurological jiggery-pokery works:

By engaging the brain in what’s called bilateral stimulation (which can be achieved in various ways, but a common one is moving the eyes rapidly from side to side, hence the name), the event can be re-processed, in much the same way that we do when dreaming, and relegated safely to the past.

This doesn’t mean you’ll forget the event; you’d need to do different exercises for that.

See also our previous main feature:

The Dark Side Of Memory (And How To Make Your Life Better)

That’s not the only aspect of EMDR, though…

EMDR is not just about recalling traumatic events while moving your eyes from side-to-side. What an easy fix that would be! There’s a little more to it.

The process also involves (ideally with the help of a trained professional) examining what other memories, thoughts, feelings, come to mind while doing that. Sometimes, a response we have today associated with, for example, a feeling of helplessness, or rage in conflict, or shame, or anything really, can be connected to previous instances of feeling the same thing. And, each of those events will reinforce—and be reinforced by—the others.

An example of this could be an adult who struggles with substance abuse (perhaps alcohol, say), using it as a crutch to avoid feelings of [insert static here; we don’t know what the feelings are because they’re being avoided], that were first created by, and gradually snowballed from, some adverse reaction to something they did long ago as a child, then reinforced at various times later in life, until finally this adult doesn’t know what to do, but they do know they must hide it at all costs, or suffer the adverse reaction again. Which obviously isn’t a way to actually overcome anything.

EMDR, therefore, seeks to not just “detooth” a singular traumatic memory, but rather, render harmless the whole thread of memories.

Needless to say, this kind of therapy can be quite an emotionally taxing experience, so again, we recommend trying it only under the guidance of a professional.

Is this an evidence-based approach?

Yes! It’s not without its controversy, but that’s how it is in the dog-eat-dog world of academia in general and perhaps psychotherapy in particular. To give a note to some of why it has some controversy, here’s a great freely-available paper that presents “both sides” (it’s more than two sides, really); the premises and claims, the criticisms, and explanations for why the criticisms aren’t necessarily actually problems—all by a wide variety of independent research teams:

Research on Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing (EMDR) as a Treatment for PTSD

To give an idea of the breadth of applications for EMDR, and the evidence of the effectiveness of same, here are a few additional studies/reviews (there are many):

- An Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Group Intervention for Syrian Refugees With Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing for Treating Panic Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in the treatment of depression: a matched pairs study in an inpatient setting

- Emergency room intervention to prevent post concussion-like symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder. A pilot randomized controlled study of a brief eye movement desensitization and reprocessing intervention versus reassurance or usual care

As for what the American Psychiatric Association says about it:

❝After assessing the 120 outcome studies pertaining to the focus areas, we conclude that for two of the areas (i.e., PTSD in children and adolescents and EMDR early interventions research) the strength of the evidence is rated at the highest level, whereas the other areas obtain the second highest level.❞

Source: The current status of EMDR therapy, specific target areas, and goals for the future

Want to learn more?

To learn a lot more than we could include here, check out the APA’s treatment guidelines (they are written in a fashion that is very accessible to a layperson):

APA | Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Don’t Do *This* If You’re Over 50 (And Want Better Sleep)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Michael Breus, sleep specialist, explains:

Don’t make these mistakes

Dr. Breus recommends avoiding…

- Misusing magnesium: magnesium is a helpful sleep aid but must be carefully monitored. Recommended doses are 250mg for women and 300–350 mg for men, with slight adjustments for hot climates or active lifestyles. Overdosing can cause stomach issues, diarrhea, and dehydration, disrupting sleep. He recommends starting with magnesium glycinate for fewer stomach issues, and later mix with magnesium citrate. Always check supplements to avoid excessive magnesium intake.

- Misusing melatonin: melatonin production declines after age 55–60, making low-dose supplementation (0.5–1 mg) beneficial. He recommends, however, avoiding high doses (3–10mg), and he recommends to take it 90 minutes before bedtime. Melatonin interacts with some medications (including some meds for blood pressure or depression), so consult a pharmacist before use to avoid risks like serotonin syndrome.

- Going to bed too early: going to bed too early disrupts circadian rhythms and reduces sleep drive, causing earlier waking. Now, being an “early bird” is a generally healthy thing, but if you’re already getting up at 5am, say, you probably want your schedule to not continue to creep further forwards until you become nocturnal. Set a consistent wake-up time and count 7.5 hours backward (plus a set time to fall asleep, e.g. 20 minutes, but you’ll know what it is for you) to determine bedtime.

- Excessive caffeine consumption: from the heading, it may seem like a no-brainer, but older adults metabolize caffeine 33% slower on average, prolonging its effects. Dr. Breus recommends to reduce intake with “caffeine fading,” switching to half-caffeinated coffee for a while and then considering transitioning to decaf. He also suggests enjoying increasingly lower-caffeine teas, like black tea in the morning, matcha in the afternoon, and herbal tea at night to reduce caffeine’s impact on sleep.

- Falling foul of serotonin: avoid taking 5-HTP supplements with SSRI antidepressants like Prozac or Zoloft due to the risk of serotonin syndrome.

- Consider checking for physical problems: if you regularly wake up tired and/or groggy (despite having ostensibly had enough sleep, and there not being a pharmaceutical explanation for your grogginess), consider screening for sleep apnea. Home sleep tests are a convenient way to identify and treat this common but often undiagnosed condition.

For more on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

How to Fall Asleep Faster: CBT-Insomnia Treatment

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Time Smart – by Dr. Ashley Whillans

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this is not: it’s not a productivity book.

What is rather: a book of better wellbeing.

There is a little overlap, insofar as getting “time smart” in the ways that Dr. Whillans recommends will give you more ability to also be more productive—if that’s what you want.

She talks us through time traps and the “time poverty epidemic”, as well as steps to finding time and funding time. Perhaps most critical idea-wise is the chapter on building a “time-affluence habit”, making decisions that prioritize your time-freedom where you can—which in turn will allow you to build yet more. Kind of like compound interest really, but for time.

The writing style is a conversational tone, but peppered with bullet-point lists and charts and the like from time to time, and often with citations to back up claims. It makes for a very readable book, and yet one that’s also inspiring of the confidence that it’s more than just one person’s opinion.

Bottom line: if you sometimes feel like you could do everything you want to if you could just find the time, this book can help you get there.

Click here to check out Time Smart, and live your most satisfying life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Ear Candling: Is It Safe & Does It Work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Does This Practice Really Hold A Candle To Evidence-Based Medicine?

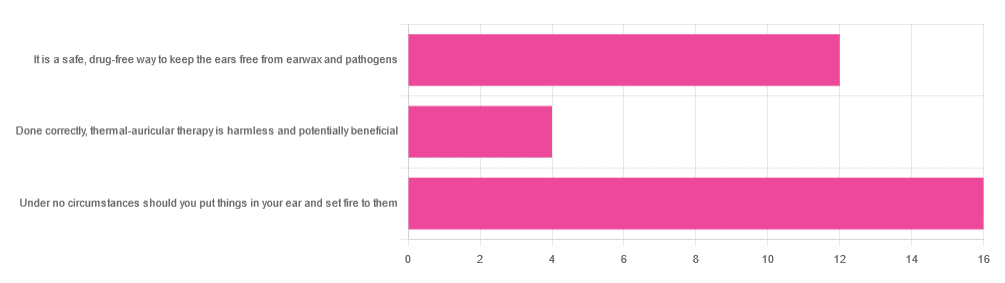

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion of ear candling, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of responses:

- Exactly 50% said “Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them”

- About 38% said “It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens”

- About 13% said “Done correctly, thermal-auricular therapy is harmless and potentially beneficial”

This means that if we add the two positive-to-candling answers together, it’s a perfect 50:50 split between “do it” and “don’t do it”.

(Yes, 38%+13%=51%, but that’s because we round to the nearest integer in these reports, and more precisely it was 37.5% and 12.5%)

So, with the vote split, what does the science say?

First, a quick bit of background: nobody seems keen to admit to having invented this. One of the major manufacturers of ear candles refers to them as “Hopi” candles, which the actual Hopi tribe has spent a long time asking them not to do, as it is not and never has been used by the Hopi people. Other proposed origins offered by advocates of ear candling include Traditional Chinese Medicine (not used), Ancient Egypt (no evidence of such whatsoever), and Atlantis:

Quackwatch | Why Ear Candling Is Not A Good Idea

It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens: True or False?

False! In a lot of cases of alternative therapy claims, there’s an absence of evidence that doesn’t necessarily disprove the treatment. In this case, however, it’s not even an open matter; its claims have been actively disproven by experimentation:

- It doesn’t remove earwax; on the contrary, experimentation “showed no removal of cerumen from the external auditory canal. Candle wax was actually deposited in some“

- It doesn’t remove pathogens, and the proposed mechanism of action for removing pathogens, that of the “chimney effect”: the idea that the burning candle creates a vacuum that draws wax out of the ear along with debris and bacteria, simply does not work; on the contrary, “Tympanometric measurements in an ear canal model demonstrated that ear candles do not produce negative pressure”.

- It isn’t safe; on the contrary, “Ear candles have no benefit in the management of cerumen and may result in serious injury”

In a medium-sized survey (n=122), the following injuries were reported:

- 13 x burns

- 7 x occlusion of the ear canal

- 6 x temporary hearing loss

- 3 x otitis externa (this also called “swimmer’s ear”, and is an inflammation of the ear, accompanied by pain and swelling)

- 1 x tympanic membrane perforation

Indeed, authors of one paper concluded:

❝Ear candling appears to be popular and is heavily advertised with claims that could seem scientific to lay people. However, its claimed mechanism of action has not been verified, no positive clinical effect has been reliably recorded, and it is associated with considerable risk.

No evidence suggests that ear candling is an effective treatment for any condition. On this basis, we believe it can do more harm than good and we recommend that GPs discourage its use❞

Source: Canadian Family Physician | Ear Candling

Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them: True or False?

True! It’s generally considered good advice to not put objects in general in your ears.

Inserting flaming objects is a definite no-no. Please leave that for the Cirque du Soleil.

You may be thinking, “but I have done this and suffered no ill effects”, which seems reasonable, but is an example of survivorship bias in action—it doesn’t make the thing in question any safer, it just means you were one of the one of the ones who got away unscathed.

If you’re wondering what to do instead… Ear oils can help with the removal of earwax (if you don’t want to go get it sucked out at a clinic—the industry standard is to use a suction device, which actually does what ear candles claim to do). For information on safely getting rid of earwax, see our previous article:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: