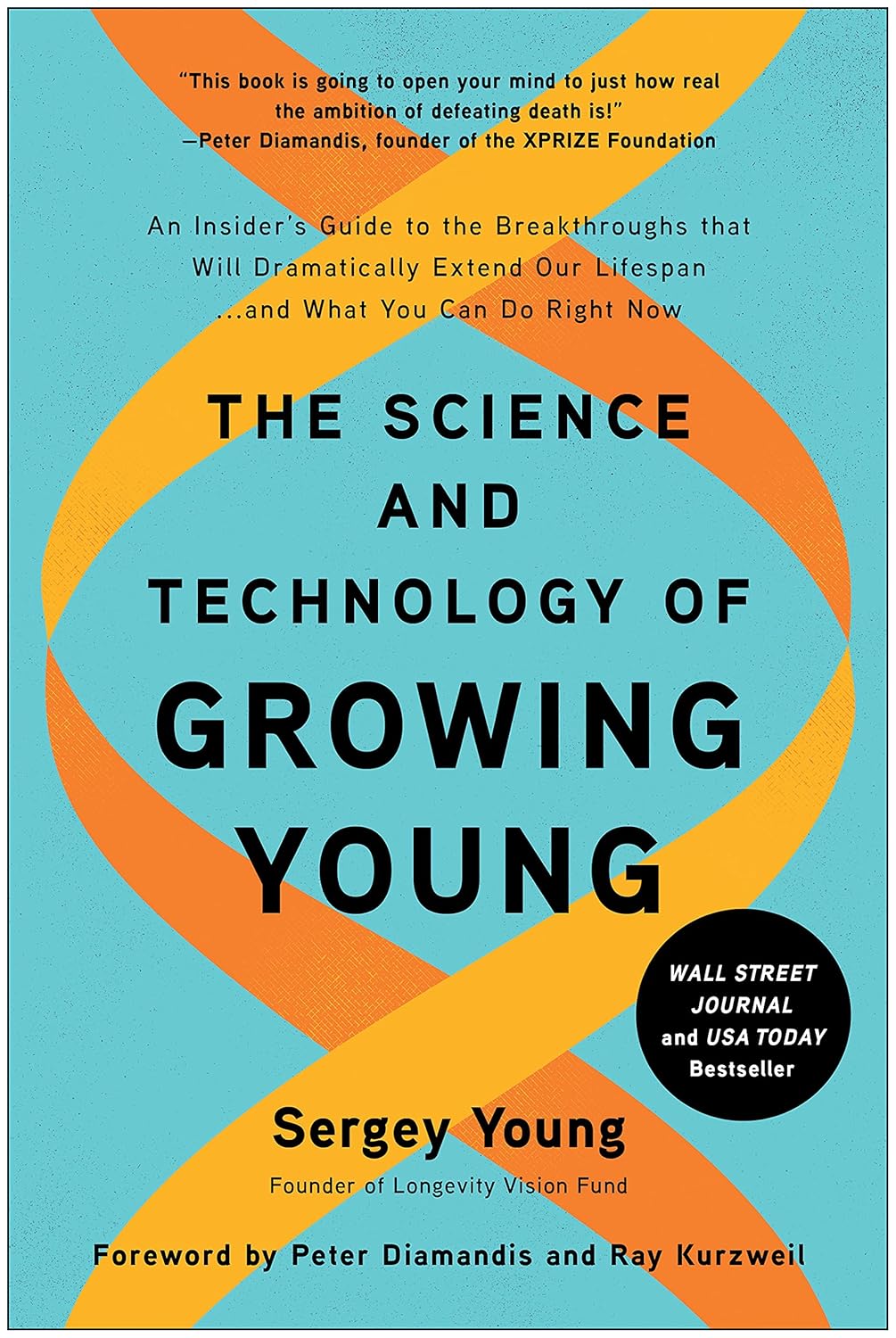

The Science and Technology of Growing Young – by Sergey Young

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are a lot of very optimistic works out there that promise the scientific breakthroughs that will occur very soon. Even amongst the hyperoptimistic transhumanism community, there is the joke of “where’s my flying car?” Sometimes prefaced with “Hey Ray, quick question…” as a nod to (or sometimes, direct address to) Ray Kurzweil, the Google computer scientist and futurist.

So, how does this one measure up?

Our author, Sergey Young, is not a scientist, but an investor with fingers in many pies. Specifically, pies relating to preventative medicine and longevity. Does that make him an unreliable narrator? Not necessarily, but it means we need to at least bear that context in mind.

But, also, he’s investing in those fields because he believes in them, and wants to benefit from them himself. In essense, he’s putting his money where his mouth is. But, enough about the author. What of the book?

It’s a whirlwind tour of the main areas of reseach and development, in the recent past, the present, and the near future. He talks about problems, and compelling solutions to problems.

If the book has a weak point, it’s that it doesn’t really talk about the problems to those solutions—that is, what can still go wrong. He’s excited about what we can do, and it’s somebody else’s job to worry about pitfalls along the way.

As to the “and what you can do now?” We’ll summarize:

- Mediterranean diet, mostly plant-based

- Get moderate exercise daily

- Get good sleep

- Don’t drink or smoke

- Get your personal health genomics data

- Get regular medical check-ups

- Look after your mental health too

Bottom line: this is a great primer on the various avenues of current anti-aging research and development, with discussion ranging from the the technological to the sociological. It has some health tips too, but the real meat of the work is the insight into the workings of the longevity industry.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Actually Causes High Cholesterol?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In 1968, the American Heart Association advised limiting egg consumption to three per week due to cholesterol concerns linked to cardiovascular disease. Which was reasonable based on the evidence available back then, but it didn’t stand the test of time.

Eggs are indeed high in cholesterol, but that doesn’t mean that those who eat them will also be high in cholesterol, because…

It’s not quite what many people think

Some quite dietary pointers to start with:

- Egg yolks are high in cholesterol but have a minimal impact on blood cholesterol.

- Saturated and trans fats (as found in fatty meats or dairy, and some processed foods) have a greater influence on LDL levels than dietary cholesterol.

And on the other hand:

- Unsaturated fats (e.g. from fish, nuts, seeds) have anti-inflammatory benefits

- Fiber-rich foods help lower LDL by affecting fat absorption in the digestive tract

A quick primer on LDL and other kinds of cholesterol:

- VLDL (Very Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- delivers triglycerides and cholesterol to muscle and fat cells for energy

- is converted into LDL after delivery

- LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- is called “bad cholesterol”, which we call that due to its role in arterial plaque formation

- in excess leads to inflammation, overworked macrophage activity, and artery narrowing

- HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein):

- known as “good cholesterol,” picks up excess LDL and returns it to the liver for excretion

- is anti-inflammatory, in addition to regulating LDL levels

There are other factors too, for example:

- Smoking and drinking increase LDL buildup and cause oxidative damage to lipids in general and the blood vessels through which they travel

- Regular exercise, meanwhile, can lower LDL and raise HDL

- Statins and other medications can help lower LDL and manage cholesterol when lifestyle changes and genetics require additional support—but they often come with serious side effects, and the usefulness varies from person to person.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Mocktails – by Moira Clark

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed books about quitting alcohol before (such as this one), but today’s is not about quitting, so much as about enjoying non-alcoholic drinks; it’s simply a recipe book of zero-alcohol cocktails, or “mocktails”.

What sets this book apart from many of its kind is that every recipe uses only natural and fresh ingredients, rather than finding in the ingredients list some pre-made store-bought component. Instead, because of its “everything from scratch” approach, this means:

- Everything is reliably as healthy as the ingredients you use

- Every recipe’s ingredients can be found easily unless you live in a food desert

Each well-photographed and well-written recipe also comes with a QR code to see a step-by-step video tutorial (or if you get the ebook version, then a direct link as well).

Bottom line: this is the perfect mocktail book to have in (and practice with!) before the summer heat sets in.

Click here to check out Mocktails: A Delicious Collection of Non-Alcoholic Drinks, and get mixing!

Share This Post

-

Carrot vs Sweet Potato – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing carrot to sweet potato, we picked the sweet potato.

Why?

Both are great! But there’s a winner in the end:

Looking at the macros first, sweet potato has more protein carbs, and fiber, and is thus the “more food per food” item. If they are both cooked the same, then the glycemic index is comparable, despite the carrot’s carbs having more sucrose and the sweet potato’s carbs having more starch. We’ll call this category a tie.

In terms of vitamins, carrots have more of vitamins B9 and K, while sweet potatoes have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6. B7, C, E, and choline. Both are equally high in vitamin A. Thus, the vitamins category is an overwhelming win for sweet potato.

When it comes to minerals, carrots are not higher in any minerals (unless we count that they are slightly higher in sodium, but that is not generally considered a plus for most people in most places most of the time), while sweet potato is higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Another easy win for sweet potato.

Adding up the sections makes for a clear win for the sweet potato as the more nutritionally dense option, but as ever, enjoy either or both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Does This New Machine Cure Depression?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Let us first talk briefly about the slightly older tech that this may replace, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

TMS involves electromagnetic fields to stimulate the left half of the brain and inhibit the right half of the brain. It sounds like something from the late 19th century—“cure your melancholy with the mystical power of magnetism”—but the thing is, it works:

The main barriers to its use are that the machine itself is expensive, and it has to be done in a clinic by a trained clinician. Which, if it were treating one’s heart, say, would not be so much of an issue, but when treating depression, there is a problem that depressed people are not the most likely to commit to (and follow through with) going somewhere probably out-of-town regularly to get a treatment, when merely getting out of the door was already a challenge and motivation is thin on the ground to start with.

Thus, antidepressant medications are more often the go-to for cost-effectiveness and adherence. Of course, some will work better than others for different people, and some may not work at all in the case of what is generally called “treatment-resistant depression”:

Antidepressants: Personalization Is Key!

Transcranial stimulation… At home?

Move over transcranial magnetic stimulation; it’s time for transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS).

First, what it’s not: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Rather, it uses a very low current.

What it is: a small and portable headset (as opposed to the big machine to go sit in for TMS) that one can use at home. Here’s an example product on Amazon, though there are more stylish versions around, this is the same basic technology.

In a recent study, 45% of those who received treatment with this device experienced remission in 10 weeks, significantly beating placebo (bearing in mind that placebo effect is strongest when it comes to invisible ailments such as depression).

See also: How To Leverage Placebo Effect For Yourself ← this explains more about how the placebo effect works, to the extent that it can even be an adjuvant tool to augment “real” therapies

And as for the study, here it is:

…which rather cuts through the “depressed people don’t make it to the clinic consistently, if at all” problem. Of course, it still requires adherence to its use at home, for example three 30-minute sessions per week, but honestly, “lie/sit still” is likely within the abilities of the majority of depressed people. However…

Important note: you remember we said “in 10 weeks”? That may be critical, because shorter studies (e.g. 6 weeks) have previously returned without such glowing results:

Home-Use Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for the Treatment of a Major Depressive Episode

This means that if you get this tech for yourself or a loved one, it’ll be necessary to persist for likely 10 weeks, certainly more than 6 weeks, and not abandon it after a few sessions when it hasn’t been life-changing yet. And that may be more of a challenge for a depressed person, so likely an “accountability buddy” of some kind is in order (partner, close friend, etc) to help ensure adherence and generally bug you/them into doing it consistently.

And then, of course, you/they might still be in the 55% of people for whom it didn’t work. And that does suck, but random antidepressant medications (i.e., not personalized) don’t fare much better, statistically.

Want something else against depression meanwhile?

Here are some strategies that not only can significantly help, but also are tailored to be actually doable while depressed:

The Mental Health First-Aid You’ll Hopefully Never Need ← written by your writer who has previously suffered extensively from depression and knows what it is like

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can You Get Addicted To MSG, Like With Sugar?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝Hello, I love your newsletter 🙂 Can I have a question? While browsing through your recepies, I realised many contained MSG. As someone based in Europe, I am not used to using MSG while cooking (of course I know that processed food bought in supermarket containes MSG). There is a stigma, that MSG is not particulary healthy, but rather it should be really bad and cause negative effects like headaches. Is this true? Also, can you get addicted to MSG, just like you get addicted to sugar? Thank you :)❞

Thank you for the kind words, and the interesting questions!

Short answer: no and no 🙂

Longer answer: most of the negative reputation about MSG comes from a single piece of satire written in the US in the 1960s, which the popular press then misrepresented as a genuine concern, and the public then ran with, mostly due to racism/xenophobia/sinophobia specifically, given the US’s historically not fabulous relations with China, and the moniker of “Chinese restaurant syndrome”, notwithstanding that MSG was first isolated in Japan, not China, more than 100 years ago.

The silver lining that comes out of this is that because of the above, MSG has been one of the most-studied food additives in recent decades, with many teams of scientists in many countries trying to determine its risks and not finding any (except insofar as anything in extreme quantities can kill you, including water or oxygen).

You can read more about this and other* myths about MSG, here:

Monosodium Glutamate: Sinless Flavor-Enhancer Or Terrible Health Risk?

*such as pertaining to gluten sensitivity, which in reality MSG has no bearing on whatsoever as it does not contain gluten and is not even made of the same basic stuff; gluten being a protein made of (amongst other things) the amino acid glutamine, not a glutamate salt. Glutamate is as closely related to gluten as cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) is to cyanide (the famous poison).

PS: if you didn’t click the above link to read that article, then 1) we really do recommend it 2) we did some LD50 calculations there and looked at available research, and found that for someone of this writer’s (very medium) size, eating 1kg of MSG at once is sufficient to cause toxicity, and injecting >250g of MSG may cause heart problems. So we don’t recommend doing that.

However, ½ tsp in a recipe that gives multiple portions is not going to get you anywhere close to the danger zone, unless you consume that entire meal by yourself hundreds of times per day. And if you do, the MSG is probably the least of your concerns.

(2 tsp of cassia cinnamon, however, is enough to cause coumarin toxicity; for this reason we recommend Ceylon (or “True” or “Sweet”) cinnamon in our recipes, as it has almost undetectable levels of coumarin)

With regard to your interesting question about addiction, first of all let’s speak briefly about sugar addiction:

Sugar addiction is, by broad scientific consensus, agreed-upon as an extant thing that does exist, and contemporary research is more looking into the “hows” and “whys” and “whats” rather than the “whether”. It is a somewhat complicated topic, because it’s halfway between what science would usually consider a chemical addiction, and what science would usually consider a behavioral addiction:

The Not-So-Sweet Science Of Sugar Addiction

The reasonable prevailing hypothesis, therefore, is that sugar simply has two moderate mechanisms of addiction, rather than one strong one.

The biochemical side of sugar addiction comes from the body’s metabolism of sugar, so this cannot be a thing for MSG, because there is nothing to metabolize in the same sense of the word (MSG being an inorganic compound with zero calories).

People can crave salt, especially when deficient in it, and MSG does contain sodium (it’s what the “S” stands for), but it contains a little under ⅓ of the sodium that table salt does (sodium chloride in whatever form, be it sea salt, rock salt, or such):

MSG vs. Salt: Sodium Comparison ← we do molecular calculations here!

Sea Salt vs MSG – Which is Healthier? ← this one for a head-to-head

However, even craving salt does not constitute an addiction; nobody is shamefully hiding their rock salt crystals under their bed and getting a fix when they feel low, and nor does withdrawal cause adverse side effects, except insofar as (once again) a person deficient in salt will crave salt.

Finally, the only other way we know of that one might wonder if MSG could be addictive, is about glutamate and glutamate receptors. The glutamate in MSG is the same glutamate (down to the atoms) as the glutamate formed if one consumes tomatoes in the presence of salt, and triggers the same glutamate receptors in the same way. We have the same number of receptors either way, and uptake is exactly the same (because again, it’s exactly the same chemical) so there is a maximum to how strong this effect can be, and that maximum is the same whatever the source of the glutamate was.

In this respect, if MSG is addictive, then so is a tomato salad with a pinch of salt: it’s not—it’s just tasty.

We haven’t cited papers in today’s article, but it’s just because we cited them already in the articles we linked, and so we avoided doubling up. Most of them are in that first link we gave 🙂

One final note

Technically anyone can develop a sensitivity to anything, so in theory someone could develop a sensitivity to MSG, just like they could for any other ingredient. Our usual legal/medical disclaimer applies.

However, it’s certainly not a common trigger, putting it well below common allergens like nuts (or less common allergens like, say, bananas), not even in the same league as common intolerances such as gluten, and less worthy of health risk warnings than, say, spinach (high in oxalates; fine for most people but best avoided if you have kidney problems).

The reason we use it in the recipes we use it in, is simply because it’s a lower-sodium alternative to salt, and while it contains a (very) tiny bit less sodium than low-sodium salt (which itself has about ⅓ the sodium of regular salt), it has more of a flavor-enhancing effect, such that one can use half as much, for a more than sixfold total sodium reduction. Which for most of us in the industrialized world, is beneficial.

Want to try some?

If today’s article has inspired you to give MSG a try, here’s an example product on Amazon 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Which Diet? Top Diets Ranked By Experts

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A panel of 69 doctors and nutritionists examined the evidence for 38 diets, and scored them in 21 categories (e.g. best for weight loss, best for heart, best against diabetes, etc).

We’ll not keep it a mystery: the Mediterranean diet has been ranked as “best overall” for the 8th year in a row.

The Mediterranean (And Its Close Friends & Relations)

We’ve written before about the Mediterranean diet, here:

The Mediterranean Diet: What Is It Good For? ← What isn’t it good for?

👆 the above article also delineates what does and doesn’t go in a Mediterranean diet—hint, it’s not just any food from the Mediterranean region!

The Mediterranean diet’s strengths come from various factors including its good plant:animal ratio (leaning heavily on the plants), colorful fruit and veg minimally processed, and the fact that olive oil is the main source of fat:

All About Olive Oil ← pretty much one of the healthiest fats we can consume, if not healthiest all-rounder fat

The Mediterranean diet also won 1st place in various more specific categories, including:

- Best against arthritis (followed by Dr. Weil’s Anti-inflammatory, MIND, DASH)

- Best for mental health (followed by MIND, Flexitarian, DASH)

- Best against diabetes (followed by Flexitarian, DASH, MIND)

- best for liver regeneration (followed by Flexitarian, Vegan, DASH, MIND)

- Best for gut heath (followed by Vegan, DASH, Flexitarian, MIND)

If you’re not familiar with DASH and MIND, there are clues in their full names: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay, and as you might well suspect, they are simply tweaked variations of the Mediterranean diet:

Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean ← DASH and MIND are the heart-healthiest and brain-healthiest versions of the Mediterranean; this article also includes a gut-healthiest version and a most anti-inflammatory version

What aren’t those best for?

The Mediterranean diet scored 1st or 2nd in most of the 21 categories, and usually had the other above-named diets keeping it company in the top few.

When it comes to weight loss, the Mediterranean scored 2nd place and wasn’t flanked by its usual friends and relations; instead in first place was commercial diet WeightWatchers (likely helped a lot by being also a peer support group), and in third place was the Volumetrics diet, which we wrote about here:

Some Surprising Truths About Hunger And Satiety

And when it comes to rapid weight loss specifically, the Mediterranean didn’t even feature in the top spots at all, because it’s simply not an extreme diet and it prioritizes health over shedding the pounds at any cost. The top in that category were mostly commercial diets:

- Jenny Craig

- Slimfast

- Keto

- Nutrisystem

- WeightWatchers

We’ve not as yet written about any of those commercial diets, but we have written about keto here:

Ketogenic Diet: Burning Fat Or Burning Out?

Want to know more?

You can click around, exploring by diet or by health category, here 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: