The Pain Relief Secret – by Sarah Warren

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one’s a book to not judge by the cover—or the title. The title is actually accurate, but it sounds like a lot of woo, doesn’t it?

Instead, what we find is a very clinical, research-led (40 pages of references!) explanation of:

- the causes of musculoskeletal pain

- how this will tend to drive us to make it worse

- what we can do instead to make it better

A lot of this, to give you an idea what to expect, hinges on the fact that bones only go where muscles allow/move them; muscles only behave as instructed by nerves, and with a good development of biofeedback and new habits to leverage neuroplasticity, we can take more charge of that than you might think.

Warning: you may want to jump straight into the part with the solutions, but if you do so without a very good grounding in anatomy and physiology, you may find yourself out of your depth with previously-explained terms and concepts that are now needed to understand (and apply) the solutions.

However, if you read it methodically cover-to-cover, you’ll find you need no prior knowledge to take full advantage of this book; the author is a very skilled educator.

Bottom line: while it’s not an overnight magic pill, the methodology described in this book is a very sound way to address the causes of musculoskeletal pain.

Click here to check out The Pain Relief Secret, and help your body undo damage done!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

A Correction, And A New, Natural Way To Boost Daily Energy Levels

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

First: a correction and expansion!

After yesterday’s issue of 10almonds covering breast cancer risks and checks, a subscriber wrote to say, with regard to our opening statement, which was:

“Anyone (who has not had a double mastectomy, anyway) can get breast cancer”

❝I have been enjoying your newsletter. This statement is misleading and should have a disclaimer that says even someone who has had a double mastectomy can get breast cancer, again. It is true and nothing…nothing is 100% including a mastectomy. I am a 12 year “thriver” (I don’t like to use the term survivor) who has had a double mastectomy. I work with a local hospital to help newly diagnosed patients deal with their cancer diagnosis and the many decisions that follow. A double mastectomy can help keep recurrence from happening but there are no guarantees. I tried to just delete this and let it go but it doesn’t feel right. Thank you!❞

Thank you for writing in about this! We wouldn’t want to mislead, and we’re always glad to hear from people who have been living with conditions for a long time, as (assuming they are a person inclined to learning) they will generally know topics far more deeply than someone who has researched it for a short period of time.

Regards a double mastectomy (we’re sure you know this already, but noting here for greater awareness, prompted by your message), a lot of circumstances can vary. For example, how far did a given cancer spread, and especially, did it spread to the lymph nodes at the armpits? And what tissue was (and wasn’t) removed?

Sometimes a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy will leave the lymph nodes partially or entirely intact, and a cancer could indeed come back, if not every last cancerous cell was removed.

A total double mastectomy, by definition, should have removed all tissue that could qualify as breast tissue for a breast cancer, including those lymph nodes. However, if the cancer spread unnoticed somewhere else in the body, then again, you’re quite correct, it could come back.

Some people have a double mastectomy without having got cancer first. Either because of a fear of cancer due to a genetic risk (like Angelina Jolie), or for other reasons (like Elliot Page).

This makes a difference, because doing it for reasons of cancer risk may mean surgeons remove the lymph nodes too, while if that wasn’t a factor, surgeons will tend to leave them in place.

In principle, if there is no breast tissue, including lymph nodes, and there was no cancer to spread, then it can be argued that the risk of breast cancer should now be the same “zero” as the risk of getting prostate cancer when one does not have a prostate.

But… Surgeries are not perfect, and everyone’s anatomy and physiology can differ enough from “textbook standard” that surprises can happen, and there’s almost always a non-zero chance of certain health outcomes.

For any unfamiliar, here’s a good starting point for learning about the many types of mastectomy, that we didn’t go into in yesterday’s edition. It’s from the UK’s National Health Service:

NHS: Mastectomy | Types of Mastectomy

And for the more sciency-inclined, here’s a paper about the recurrence rate of cancer after a prophylactic double mastectomy, after a young cancer was found in one breast.

The short version is that the measured incidence rate of breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy was zero, but the discussion (including notes about the limitations of the study) is well worth reading:

Breast Cancer after Prophylactic Bilateral Mastectomy in Women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation

❝[Can you write about] the availability of geriatric doctors Sometimes I feel my primary isn’t really up on my 70 year old health issues. I would love to find a doctor that understands my issues and is able to explain them to me. Ie; my worsening arthritis in regards to food I eat; in regards to meds vs homeopathic solutions.! Thanks!❞

That’s a great topic, worthy of a main feature! Because in many cases, it’s not just about specialization of skills, but also about empathy, and the gap between studying a condition and living with a condition.

About arthritis, we’re going to do a main feature specifically on that quite soon, but meanwhile, you might like our previous article:

Keep Inflammation At Bay (arthritis being an inflammatory condition)

As for homeopathy, your question prompts our poll today!

(and then we’ll write about that tomorrow)

Share This Post

-

What’s Your Vascular Dementia Risk?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We often say that “what’s good for your heart is good for your brain”, and this is because the former feeds the latter, with oxygen and nutrients, and also clears away detritus like beta-amyloid (associated with Alzheimer’s) and alpha-synuclein (associated with Parkinson’s).

For more on those, see: How To Clean Your Brain (Glymphatic Health Primer)

For this reason, there are many risk factors that apply equally cardiovascular disease (CVD), and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and other vascular dementias, as well as stroke risk.

The link between the two has also been studied; recently a team of scienists led by Dr. Anisa Dhana asked the question:

❝What is the association between cardiovascular health (CVH) and biomarkers of neurodegeneration, including neurofilament light chain and total tau?❞

To answer this, they looked at data from more than 10,000 Americans aged 65+; of these, they were able to get serum samples from 5,470 of them, and tested those samples for the biomarkers of neurodegeneration mentioned above.

They then tabulated the results with cardiovascular health scores based on the American Heart Association (AHA)’s “Life’s Simple 7” tool, and found, amongst other things:

- 34.6% of participants carried the APOE e4 allele, a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s.

- Higher CVH scores were associated with lower NfL levels, but not with t-tau concentrations.

- APOE e4 carriers with high CVH had significantly lower NfL levels.

- Race did not influence the CVH-NfL relationship.

- Higher CVH was linked to a slower annual increase in NfL levels but did not affect t-tau changes.

- Over 10 years, participants with the lowest CVH scores saw a 7.1% annual increase in NfL levels, while those with the highest CVH scores had a 5.2% annual increase.

- Better CVH is linked to lower serum NfL levels, regardless of age, sex, or race.

- CVH is particularly crucial for APOE e4 carriers

In other words: higher cardiovascular health meant lower markers of neurodegeneration, and this not only still held true for APOE e4 carriers, but also, the benefits actually even more pronounced in those participants.

You may be wondering: “but it said it helped with NfL levels, not t-tau concentrations?” And, indeed, it is so. But this means that the overall neurodegeneration risk is still inversely proportional to cardiovascular health; it just means it’s not a magical panacea and we must still do other things too.

See also: How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

And as for the study, you can read the paper itself in full here:

Cardiovascular Health and Biomarkers of Neurodegenerative Disease in Older Adults

Life’s Simple 7

We mentioned that they used the AHA’s “Life’s Simple 7” tool to assess cardiovascular health; it is indeed simple, but important. Here it is:

Metric Poor Intermediate Ideal Current smoking Yes Former ≤12 mo Never or quit >12 mo BMI, kg/m2 ≥30 25–29.9 <25 Physical activity None 1–149 min/wk of moderate activity or 1–74 min/wk of vigorous activity or 1–149 min/wk of moderate and vigorous activity ≥150 min/wk of moderate activity or ≥75 min/wk of vigorous activity or ≥150 min/wk of moderate and vigorous activity Diet pattern score* 0–1 2–3 4–5 Total cholesterol, mg/dL ≥240 200–239 or treated to goal <200 Blood pressure, mm Hg SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90 SBP 120–139 or DBP 80–89 or treated to goal <120/<80 Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL ≥126 100–125 or treated to goal <100 *Each of the following 5 diet elements is given a score of 1: (1) ≥4.5 cups/day of fruits and vegetables; (2) ≥2 servings/week of fish; (3) ≥3 servings/day of whole grains; (4) no more than 36 oz/wk of sugar‐sweetened beverages; and (5) no more than 1500 mg/d of sodium.

As the AHA notes,

❝Unfortunately, 99% of the U.S. adult population has at least one of seven cardiovascular health risks: tobacco use,

poor diet, physical inactivity, unhealthy weight, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or high blood glucose.❞It then goes on to talk about the financial burden of this on employers, but this was taken from a workplace health resource, and we recognize the rest of it won’t be of pressing concern for most of our readers. In case you are interested though, here it is:

American Heart Association | Life’s Simple 7® Journey to Health™

For a more practical (if you’re just a private individual and employee healthcare is not your main concern) overview, see:

Want to know more?

Here are some very good starting points for improving each of those 7 metrics, as necessary:

- Which Addiction-Quitting Methods Work Best?

- How To Lose Weight (Healthily!)

- The Doctor Who Wants Us To Exercise Less, & Move More

- Which Diet? Top Diets Ranked By Experts

- Lower Cholesterol Naturally, Without Statins

- 10 Ways To Lower Blood Pressure Naturally

- 10 Ways To Balance Your Blood Sugars

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Are Squats the Ultimate Game-Changer?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Jess Grochowsky, PT, DPT, MTC, CLT, CMPTP, says the answer is yes, and here’s why:

The most complete exercise

Squats are a powerful full-body exercise that targets legs, core, and (when weights are used) upper body. All in all, they enhance strength, mobility, metabolism, and joint health, making them essential for longevity and maintaining quality of movement throughout life.

In particular, they allow a much greater range of movement through more dimensions than most exercises do, meaning that (unlike a lot of more linear exercises) they build functional strength that sees us well in everyday life—mobility, joint control, and muscle stability.

Proper Squat Technique:

- The squat involves lowering the center of mass (which is slightly behind your navel and slightly down; exact position depends on your body composition and proportions) toward the floor.

- Use the “head to hips” principle to maintain a straight spine: as the head moves forward, the hips go back.

- Different foot positions (sumo, narrow, etc) target various muscles.

4 key variables to adjust squats:

- Base of support: the surface you stand on (firm vs unstable like a Bosu ball) affects stability and muscle engagement.

- Foot position: wide stances increase stability and target inner thighs and glutes; narrow stances focus more on quads.

- Weights: can use free weights, kettlebells, or bars. Adding weights increases intensity and can incorporate upper body exercises (e.g. bicep curls, overhead presses, etc).

- Squat depth: ranges from partial to deep squats, depending on functional goals.

Types of squats and variations given in the video:

- Firm surface squats: provide stability and allow even weight distribution.

- Unstable surface squats: engage smaller stabilizing muscles.

- Yoga ball squats: shift the center of mass backward, increasing quad and glute activation.

- Weighted squats: add resistance to increase muscle load and core stability (e.g. one-sided weights for oblique engagement).

- Dynamic weighted squats: incorporate quick movements, like kettlebell swings, for power and coordination.

- Single-leg squats: enhance balance and increase workload on one side of the body.

For more on all of these plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Currants vs Grapes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing currants to grapes, we picked the currants.

Why?

First, a note on nomenclature: when we say “currants”, we are talking about actual currants, of the Ribes genus, and in this case (as per the image) red ones. We are not talking about “currants” that are secretly tiny grapes that also get called currants in the US. So, there are important botanical differences here, beyond how they have been cultivated; they are literally entirely different plants.

So, about those differences…

In terms of macros, currants have nearly 5x the fiber, while grapes are slightly higher in carbs. So there’s an easy choice here in terms of fiber and on the glycemic index front; currants win easily.

In the category of vitamins, currants have more of vitamins B5, B9, C, and choline, while grapes have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, E, and K. So, a win for grapes in this round.

When it comes to minerals, currants have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while grapes have more manganese. A win, therefore, for currants again this time.

In terms of polyphenols, currants have a lot more in terms of total polyphenols, including (as a matter of interest) approximately 5x the resveratrol content compared to grapes—and that’s compared to black grapes, which are the “best” kind of grapes for such. Grapes really aren’t a very good source of resveratrol; people just really like the idea of red wine being a health food, so it has been talked up a lot and got a popular reputation despite its extreme paucity of nutritional value.

In any case, adding up the sections makes for a clear overall win for currants, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

21 Most Beneficial Polyphenols & What Foods Have Them

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Eggplant vs Zucchini – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing eggplant to zucchini, we picked the zucchini.

Why?

In terms of macros, eggplant has more carbs and fiber while zucchini has more protein; we’ll generally prioritize fiber, so call this a subjective win for eggplant in this category, though an argument could be made for a tie.

In the category of vitamins, eggplant has more of vitamins B3, B5, and E, while zucchini has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, B9, C, K, and choline, scoring a win for zucchini here.

Looking at minerals, eggplant has more copper, manganese, and selenium, while zucchini has more calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium and zinc, meaning another win for zucchini in this round.

In terms of polyphenols, eggplant has a greater variety of polyphenols, while zucchini has greater total mass of polyphenols, so we’re calling this one a tie.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for zucchini, but by all means enjoy either or both (perhaps together!); diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

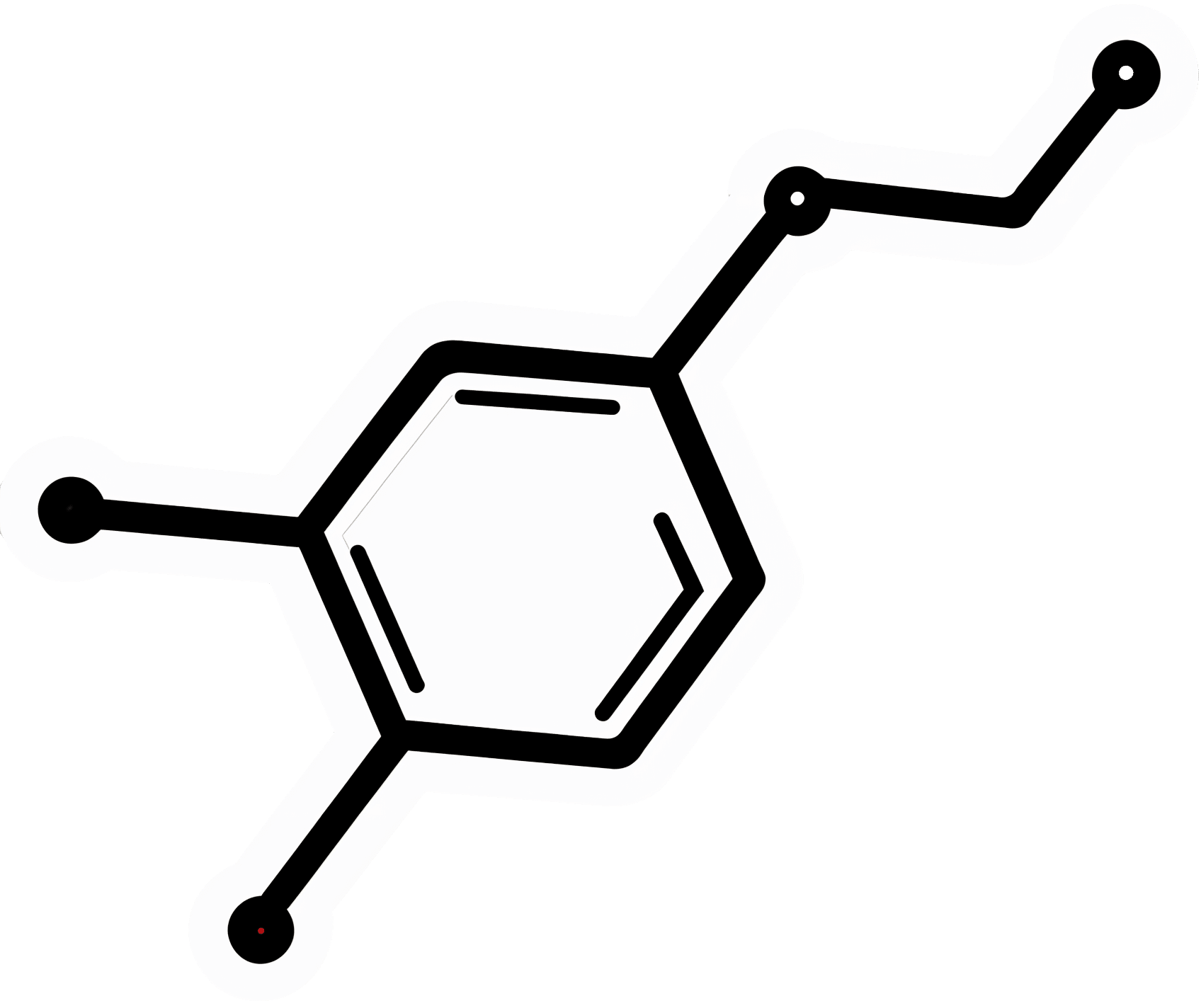

Wakefulness, Cognitive Enhancement, AND Improved Mood?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Old Drug, New Tricks?

Modafinil (also known by brand names including Modalert and Provigil) is a dopamine uptake inhibitor.

What does that mean? It means it won’t put any extra dopamine in your brain, but it will slow down the rate at which your brain removes naturally-occuring dopamine.

The result is that your brain will get to make more use of the dopamine it does have.

(dopamine is a neutrotransmitter that allows you to feel wakeful and happy, and perform complex cognitive tasks)

Modafinil is prescribed for treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness. Often that’s caused by shift work sleep disorder, sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, or narcolepsy.

Read: Overview of the Clinical Uses, Pharmacology, and Safety of Modafinil

Many studies done on humans (rather than rats) have been military experiments to reduce the effects of sleep deprivation:

Click Here To See A Military Study On Modafinil!

They’ve found modafinil to be helpful, and more effective and more long-lasting than caffeine, without the same “crash” later. This is for two reasons:

1) while caffeine works by blocking adenosine (so you don’t feel how tired you are) and by constricting blood vessels (so you feel more ready-for-action), modafinil works by allowing your brain to accumulate more dopamine (so you’re genuinely more wakeful, and you get to keep the dopamine)

2) the biological half-life of modafinil is 12–15 hours, as opposed to 4–8 hours* for caffeine.

*Note: a lot of sources quote 5–6 hours for caffeine, but this average is misleading. In reality, we are each genetically predetermined to be either a fast caffeine metabolizer (nearer 4 hours) or a slow caffeine metabolizer (nearer 8 hours).

What’s a biological half-life (also called: elimination half-life)?

A substance’s biological half-life is the time it takes for the amount in the body to be reduced by exactly half.

For example: Let’s say you’re a fast caffeine metabolizer and you have a double-espresso (containing 100mg caffeine) at 8am.

By midday, you’ll have 50mg of caffeine left in your body. So far, so simple.

By 4pm you might expect it to be gone, but instead you have 25mg remaining (because the amount halves every four hours).

By 8pm, you have 12.5mg remaining.

When midnight comes and you’re tucking yourself into bed, you still have 6.25mg of caffeine remaining from your morning coffee!

Use as a nootropic

Many healthy people who are not sleep-deprived use modafinil “off-label” as a nootropic (i.e., a cognitive enhancer).

Read: Modafinil for cognitive neuroenhancement in healthy non-sleep-deprived subjects: A systematic review

Important Note: modafinil is prescription-controlled, and only FDA-approved for sleep disorders.

To get around this, a lot of perfectly healthy biohackers describe the symptoms of sleep pattern disorder to their doctor, to get a prescription.

We do not recommend lying to your healthcare provider, and nor do we recommend turning to the online “grey market”.

Such websites often use anonymized private doctors to prescribe on an “informed consent” basis, rather than making a full examination. Those websites then dispense the prescribed medicines directly to the patient with no further questions asked (i.e. very questionable practices).

Caveat emptor!

A new mood-brightener?

Modafinil was recently tested head-to-head against Citalapram for the treatment of depression, and scored well:

See its head-to-head scores here!

How does it work? Modafinil does for dopamine what a lot of anti-depressants do for serotonin. Both dopamine and serotonin promote happiness and wakefulness.

This is very promising, especially as modafinil (in most people, at least) has fewer unwanted side-effects than a lot of common anti-depressant medications.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: