Reading As A Cognitive Exercise

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Reading, Better

It is relatively uncontroversial to say that reading is good for cognitive health, but we don’t like to make claims without science if we can help it, so let’s get started:

There was a 2021 study, which found that even when controlling for many other factors, including highest level of education, socioeconomic status, and generalized pre-morbid intelligence:

❝high reading activity, as defined by almost daily reading, was associated with lower odds of cognitive decline, compared to low reading activity❞

Source: Can reading increase cognitive reserve?

However, not all reading is the same. And this isn’t just about complexity or size of vocabulary, either. It’s about engagement.

And that level of engagement remains the key factor, no matter how quickly or slowly someone reads, as the brain tends to automatically adjust reading speed per complexity, because the brain’s “processing speed” remains the same:

Read more: Cognitive coupling during reading

Everyone’s “processing speed” is different (and is associated with generalized intelligence and executive functions), though as a general rule of thumb, the more we practice it, the faster our processing speed gets. So if you balked at the notion of “generalized intelligence” being a factor, be reassured that this association goes both ways.

So is the key to just read more?

That’s a great first step! But…

The key factor still remains: engagement.

So what does that mean?

It is not just the text that engages you. You must also engage the text!

This is akin to the difference between learning to drive by watching someone else do it, and learning by getting behind the wheel and having a go.

When it comes to reading, it should not be a purely passive thing. Sure, if you are reading a fiction book at bedtime, get lost in it, by all means. But when it comes to non-fiction reading, engage with it actively!

For example, I (your writer here, hi), when reading non-fiction:

- Read at what is generally considered an unusually fast pace, but

- Write so many notes in the margins of physical books, and

- Write so many notes using the “Notes” function on my Kindle

And this isn’t just like a studious student taking notes. Half the time I am…

- objecting to content (disagreeing with the author), or

- at least questioning it, or which is especially important, or

- noting down questions that came to my mind as a result of what I am reading.

This latter is a bit like:

- when you are reading 10almonds, sometimes you will follow our links and go off down a research rabbit-hole of your own, and that’s great!

- sometimes you will disagree with something and write to tell us, and that’s great too (when this happens, one or the other or all of us will learn something, and yes, we have published corrections before now)!

- sometimes what you read here will prompt a further question, and you’ll send that to us, and guess what, also great! We love questions.

Now, if your enjoyment of 10almonds is entirely passive, don’t let us stop you (we know our readers like quick-and-easy knowledge, and that’s good too), it’s just, the more you actively engage with it, the more you’ll get out of it.

This, by the way, was also a lifelong habit of Leonardo da Vinci, which you can read about here:

How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day – by Michael J. Gelb

a very good book that we reviewed last year

How you read (i.e. what medium) matters too!

Are you reading this on a desktop/laptop, or a mobile device? That difference could matter more than the difference between paper and digital, according to this study from 2020 that found…

❝The cumulation of evidence from this and previous studies suggests that reading on a tablet affords different interactions between the reader and the text than reading on a computer screen.

Reading on a tablet might be more similar to reading on paper, and this may impact the attentional processes during reading❞

What if my mind wanders easily?

You can either go with it, or train to improve focus.

Going with it: just make sure you have more engaging reading to get distracted by. It’s all good.

Training focus: this is trickier, but worthwhile, as executive function (you will remember from earlier) was an important factor too, and training focus is training executive function.

As for one way to do that…

If you’d like a primer for getting going with that, then you may enjoy our previous main feature:

No-Frills, Evidence-Based Mindfulness

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Ageless Athletes – by Dr. Jim Madden

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is an approach to strength and fitness training specifically for the 50+ crowd, and/but even more specifically for the 50+ crowd who do not wish to settle for mediocrity. In short, it’s for those who not only wish to stay healthy and have good mobility, but also who wish to be and remain athletic.

It does not assume extant athleticism, but nor does it assume complete inexperience. It provides a fairly ground-upwards entry to a training program that then quickly proceeds to competitive levels of athleticism.

The author himself details his own journey from being in his 30s, overweight and unfit, to being in his 50s and very athletic, with before and after photos. Granted, those are 20 years in between, but all the same, it’s a good sign when someone gets stronger and fitter with age, rather than declining.

The style of the book is quite casual, and/but after the introductory background and pep talk, is quite pragmatic and drops the additional fluff. In particular, older readers may enjoy the “Old Workhorse” protocol, as a tailored measured progression system.

In terms of expected equipment by the way, some is bodyweight and some is with weights; kettlebells in particular feature strongly, since this is about functional strength and not bodybuilding.

In the category of criticism, he does refer to his other books and generally assumes the reader is reading all his work, so it may not be for everyone as a standalone book.

Bottom line: if you’re 50+ and are wondering how to gain/maintain a high level athleticism, this book can definitely help with that.

Click here to check out Ageless Athlete, and go from strength to strength!

Share This Post

-

Toasted Chick’n Mango Tacos

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Tacos aren’t generally held up as the world’s healthiest food, but they can be! There’s so much going on in this dish today, healthwise, in a good way, that it’s hard to know where to start. But suffice it to say, these tacos are great for your gut, heart, blood sugars, and more.

You will need

For the chickpeas:

- 1 can chickpeas, drained

- 1 tbsp ras el-hanout*

- 1 tsp red pepper flakes

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Extra virgin olive oil

*You can easily make this yourself; following our recipe (linked above in the ingredients list) will be better than buying it ready-made, and if you have strong feelings about any of the ingredients, you can adjust per your preference.

For the tahini sauce:

- ⅓ cup tahini

- 2 tbsp apple cider vinegar

- 2 tbsp finely chopped fresh dill

- ¼ bulb garlic, minced

- 1 tsp red pepper flakes

- ½ tsp black pepper, coarse ground

It may seem like salt is conspicuous by its absence, but there is already enough in the chickpeas component; you do not want to overwhelm the dish. Trust us that enjoying these things together will be well-balanced and delicious as written.

For the mango relish:

- ½ mango, pitted, peeled, and cubed

- 2 tsp apple cider vinegar

- 2 tsp cilantro, finely chopped (substitute with parsley if you have the “cilantro tastes like soap” gene)

- 1 tsp red pepper flakes

For building the taco:

- Soft corn tortillas

- Handful of arugula

- 1 avocado, pitted, peeled, and sliced

- ½ red onion, sliced

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat a sauté pan with a little olive oil in; add the chickpeas and then the rest of the ingredients from the chickpea section; cook for about 5 minutes, stirring frequently, and set aside.

2) Combine the tahini sauce ingredients in a small bowl, stirring in ¼ cup water, and set aside.

3) Combine the mango relish ingredients in a separate small bowl, and set aside. You can eat the other half of the mango if you like.

4) Lightly toast the tortillas in a dry skillet, or using a grill.

5) Assemble the tacos; we recommend the order: tortillas, arugula, avocado slices, chickpeas, mango relish, red onion slices, tahini sauce.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← we hit all five today! Yay!

- An Apple (Cider Vinegar) A Day…

- Coconut vs Avocado – Which is Healthier?

- Lettuce vs Arugula – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Latest Alzheimer’s Prevention Research Updates

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Questions and Answers at 10almonds

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

This newsletter has been growing a lot lately, and so have the questions/requests, and we love that! In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

I am now in the “aging” population. A great concern for me is Alzheimers. My father had it and I am so worried. What is the latest research on prevention?

One good thing to note is that while Alzheimer’s has a genetic component, it doesn’t appear to be hereditary per se. Still, good to be on top of these things, and it’s never too early to start with preventive measures!

You might like a main feature we did on this recently:

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

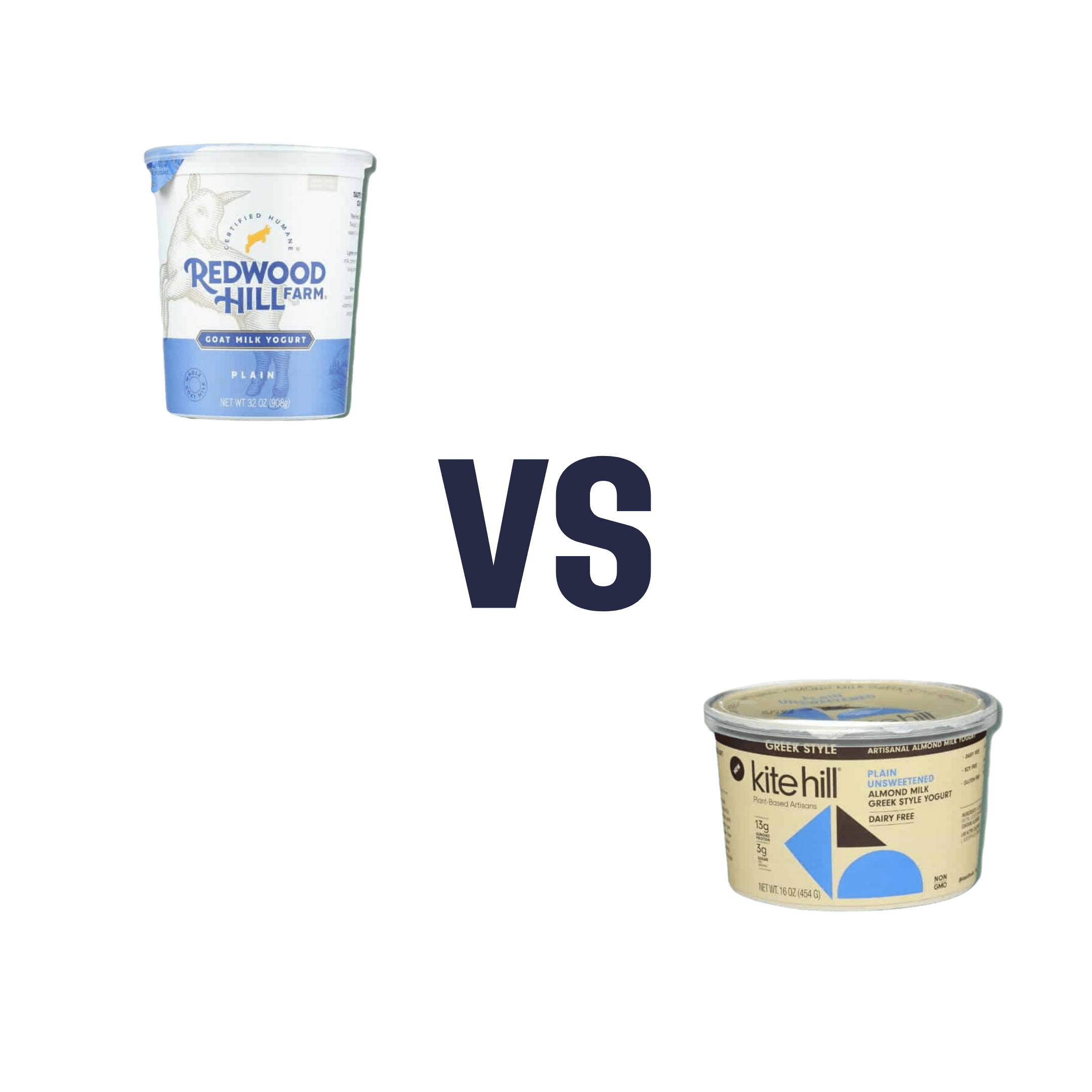

Goat Milk Greek Yogurt vs Almond Milk Greek Yogurt – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing goat milk yogurt to almond milk yogurt, we picked the almond milk yogurt.

Why?

Surprised? Honestly, we were too!

Much as we love almonds, we were fully expecting to write about how they’re very close in nutritional value, but the dairy yogurt has more probiotics, but no, as it turns out when we looked into them, they’re quite comparable in that regard.

It’s easy to assume “goat milk yogurt is more natural and therefore healthier”, but in both cases, it was a case of taking a fermentable milk, and fermenting it (an ancient process). “But almond milk is a newfangled thing”, well, new-ish…

So what was the deciding factor?

In this case, the almond milk yogurt has about twice the protein per (same size) serving, compared to the goat milk; all the other macros are about the same, and the micronutrients are similar. Like many plant-based milks and yogurts, this one is fortified with calcium and vitamin D, so that wasn’t an issue either.

In short: the only meaningful difference was the protein, and the almond came out on top.

However!

The almond came out on top only because it is strained; this can be done (or not) with any kind of yogurt, be it from an animal or a plant.

In other words: if it had been different brands, the goat milk yogurt could have come out on top!

The take-away idea here is: always read labels, because as you’ve just seen, even we can get surprised sometimes!

seriously if you only remember one thing from this today, make it the above

Other thing worth mentioning: yogurts, and dairy products in general, are often made with common allergens (e.g. dairy, nuts, soy, etc). So if you are allergic or intolerant, obviously don’t choose the one to which you are allergic or intolerant.

That said… If you are lactose-intolerant, but not allergic, goat’s milk does have less lactose than cow’s milk. But of course, you know your limits better than we can in this regard.

Want to try some?

Amazon is not coming up with the goods for this one (or anything even similar, at time of writing), so we recommend trying your local supermarket (and reading labels, because products vary widely!)

What you’re looking for (be it animal- or plant-based):

- Live culture probiotic bacteria

- No added sugar

- Minimal additives in general

- Lastly, check out the amounts for protein, calcium, vitamin D, etc.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

100 Hikes of a Lifetime – by Kate Siber

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is published by National Geographic, so you can imagine the quality of the photos throughout.

Inside, and after a general introduction and guide to gear and packing appropriately, it’s divided into continents, with a diverse array of “trips of a lifetime” for anyone who enjoys hiking.

It’s not a narrative book, rather, it is a guide, a little in the style of “Lonely Planet”, with many “know before you go” tips, information about the best time to go, difficult level, alternative routes if you want to get most of the enjoyment while having an easier time of it (or, conversely, if you want to see some extra sights along the way), and what to expect at all points.

Where the book really excels is in balancing inspiration with information. There are some books that make you imagine being in a place, but you’ll never actually go there. There are other books that are technical manuals but not very encouraging. This one does both; it provides the motivation and the “yes, you really can, here’s how” information that, between them, can actually get you packing and on your way.

Bottom line: if you yearn for breathtaking views and time in the great outdoors, but aren’t sure where to start, this will give you an incredible menu to choose from, and give you the tools to go about doing it.

Click here to check out 100 Hikes Of A Lifetime, and live it!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Paulina Porizkova (Former Supermodel) Talks Menopause, Aging, & Appearances

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Are supermodels destined to all eventually become “Grizabella the Glamor Cat”, a washed-up shell of their former glory? Is it true that “men grow cold as girls grow old, and we all lose our charms in the end”? And what—if anything—can we do about it?

Insights from a retired professional

Paulina Porizkova is 56, and she looks like she’s… 56, maybe? Perhaps a little younger or a bit older depending on the camera and lighting and such.

It’s usually the case, on glossy magazine covers and YouTube thumbnails, that there’s a 20-year difference between appearance and reality, but not here. Why’s that?

Porizkova noted that many celebrities of a similar age look younger, and felt bad. But then she noted that they’d all had various cosmetic work done, and looked for images of “real” women in their mid-50s, and didn’t find them.

Note: we at 10almonds do disagree with one thing here: we say that someone who has had cosmetic work done is no less real for it; it’s a simple matter of personal choice and bodily autonomy. She is, in our opinion, making the same mistake as people make when they say such things as “real people, rather than models”, as though models are not also real people.

Porizkova found modelling highly lucrative but dehumanizing, and did not enjoy the objectification involved—and she enjoyed even less, when she reached a certain age, negative comments about aging, and people being visibly wrong-footed when meeting her, as they had misconceptions based on past images.

As a child and younger adult through her modelling career, she felt very much “seen and not heard”, and these days, she realizes she’s more interesting now but feels less seen. Menopause coincided with her marriage ending, and she felt unattractive and ignored by her husband; she questioned her self-worth, and felt very bad about it. Then her husband (they had separated, but had not divorced) died, and she felt even more isolated—but it heightened her sensitivity to life.

In her pain and longing for recognition, she reached out through her Instagram, crying, and received positive feedback—but still she struggles with expressing needs and feeling worthy.

And yet, when it comes to looks, she embraces her wrinkles as a form of expression, and values her natural appearance over cosmetic alterations.

She describes herself as a work in progress—still broken, still needing cleansing and healing, but proud of how far she’s come so far, and optimistic with regard to the future.

For all this and more in her own words, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

The Many Faces Of Cosmetic Surgery

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: