Radishes vs Endives – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing radishes to endives, we picked the endives.

Why?

These are both great, but there’s a clear winner here in every category!

In terms of macros, radishes have more carbs while endives have more fiber and protein.

In the category of vitamins, radishes have more of vitamins B6 and C, while endives have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B4, B5, B7, B9, E, K, and choline.

When it comes to minerals, things are not less one-sided: radishes have more selenium, while endives have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc.

You may be thinking: but what about radishes’ shiny red bit? Doesn’t that usually mean more of something important, like carotenoids or anthocyanins or something? And the answer is that the red pigment in radishes is so thinly-distributed on the exterior that it’s barely there and if we’re looking at values per 100g, it’s a tiny fraction of a tiny fraction.

In both cases, their bitter taste comes mostly from flavonols, of which mostly kaempferol, of which endives have about 20x what radishes have, on average.

All in all, an overwhelming win for endives.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Uses of Delusion – by Dr. Stuart Vyse

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most of us try to live rational lives. We try to make the best decisions we can based on the information we have… And if we’re thoughtful, we even try to be aware of common logical fallacies, and overcome our personal biases too. But is self-delusion ever useful?

Dr. Stuart Vyse, psychologist and Fellow for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, argues that it can be.

From self-fulfilling prophecies of optimism and pessimism, to the role of delusion in love and loss, Dr. Vyse explores what separates useful delusion from dangerous irrationality.

We also read about such questions as (and proposed answers to):

- Why is placebo effect stronger if we attach a ritual to it?

- Why are negative superstitions harder to shake than positive ones?

- Why do we tend to hold to the notion of free will, despite so much evidence for determinism?

The style of the book is conversational, and captivating from the start; a highly compelling read.

Bottom line: if you’ve ever felt yourself wondering if you are deluding yourself and if so, whether that’s useful or counterproductive, this is the book for you!

Click here to check out The Uses of Delusion, and optimize yours!

Share This Post

-

Cognitive Enhancement Without Drugs

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cognitive Enhancement Without Drugs

This is Elizabeth Ricker. She’s a Harvard-and-MIT-trained neuroscientist and researcher, who now runs the “Citizen Science” DIY-neurohacking organization, NeuroEducate.

Sounds fun! What’s it about?

The philosophy that spurs on her research and practice can be summed up as follows:

❝I’m not going to leave my brain up to my doctor or [anyone else]… My brain is my own responsibility, and I’m going to do the best that I can to optimize it❞

Her goal is not just to optimize her own brain though; she wants to make the science accessible to everyone.

What’s this about Citizen Science?

“Citizen Science” is the idea that while there’s definitely an important role in society for career academics, science itself should be accessible to all. And, not just the conclusions, but the process too.

This can take the form of huge experiments, often facilitated these days by apps where we opt-in to allow our health metrics (for example) to be collated with many thousands of others, for science. It can also involve such things as we talked about recently, getting our own raw genetic data and “running the numbers” at home to get far more comprehensive and direct information than the genetic testing company would ever provide us.

For Ricker, her focus is on the neuroscience side of biohacking, thus, neurohacking.

I’m ready to hack my brain! Do I need a drill?

Happily not! Although… Bone drills for the skull are very convenient instruments that make it quite hard to go wrong even with minimal training. The drill bit has a little step/ledge partway down, which means you can only drill through the thickness of the skull itself, before the bone meeting the wider part of the bit stops you from accidentally drilling into the brain. Still, please don’t do this at home.

What you can do at home is a different kind of self-experimentation…

If you want to consider which things are genuinely resulting in cognitive enhancement and which things are not, you need to approach the matter like a scientist. That means going about it in an organized fashion, and recording results.

There are several ways cognitive enhancement can be measured, including:

- Learning and memory

- Executive function

- Emotional regulation

- Creative intelligence

Let’s look at each of them, and what can be done. We don’t have a lot of room here; we’re a newsletter not a book, but we’ll cover one of Ricker’s approaches for each:

Learning and memory

This one’s easy. We’re going to leverage neuroplasticity (neurons that fire together, wire together!) by simple practice, and introduce an extra element to go alongside your recall. Perhaps a scent, or a certain item of clothing. Tell yourself that clinical studies have shown that this will boost your recall. It’s true, but that’s not what’s important; what’s important is that you believe it, and bring the placebo effect to bear on your endeavors.

You can test your memory with word lists, generated randomly by AI, such as this one:

You’ll soon find your memory improving—but don’t take our word for it!

Executive function

Executive function is the aspect of your brain that tells the other parts how to work, when to work, and when to stop working. If you’ve ever spent 30 minutes thinking “I need to get up” but you were stuck in scrolling social media, that was executive dysfunction.

This can be trained using the Stroop Color and Word Test, which shows you words, specifically the names of colors, which will themselves be colored, but not necessarily in the color the word pertains to. So for example, you might be shown the word “red”, colored green. Your task is to declare either the color of the word only, ignoring the word itself, or the meaning of the word only, ignoring its appearance. It can be quite challenging, but you’ll get better quite quickly:

The Stroop Test: Online Version

Emotional Regulation

This is the ability to not blow up angrily at the person with whom you need to be diplomatic, or to refrain from laughing when you thought of something funny in a sombre situation.

It’s an important part of cognitive function, and success or failure can have quite far-reaching consequences in life. And, it can be trained too.

There’s no online widget for this one, but: when and if you’re in a position to safely* do so, think about something that normally triggers a strong unwanted emotional reaction. It doesn’t have to be something life-shattering, but just something that you feel in some way bad about. Hold this in your mind, sit with it, and practice mindfulness. The idea is to be able to hold the unpleasant idea in your mind, without becoming reactive to it, or escaping to more pleasant distractions. Build this up.

*if you perchance have PTSD, C-PTSD, or an emotional regulation disorder, you might want to talk this one through with a qualified professional first.

Creative Intelligence

Another important cognitive skill, and again, one that can be cultivated and grown.

The trick here is volume. A good, repeatable test is to think of a common object (e.g. a rock, a towel, a banana) and, within a time constraint (such as 15 minutes) list how many uses you can think of for that item.

Writer’s storytime: once upon a time, I was sorting through an inventory of medical equipment with a colleague, and suggested throwing out our old arterial clamps, as we had newer, better ones—in abundance. My colleague didn’t want to part with them, so I challenged him “Give me one use for these, something we could in some possible world use them for that the new clamps don’t do better, and we’ll keep them”. He said “Thumbscrews”, and I threw my hands up in defeat, saying “Fine!”, as he had technically fulfilled my condition.

What’s the hack to improve this one? Just more volume. Creativity, as it turns out, isn’t something we can expend—like a muscle, it grows the more we use it. And because the above test is repeatable (with different objects), you can track your progress.

And if you feel like using your grown creative muscle to write/paint/compose/etc your magnum opus, great! Or if you just want to apply it to the problem-solving of everyday life, also great!

In summary…

Our brain is a wonderful organ with many functions. Society expects us to lose these as we get older, but the simple, scientific truth is that we can not only maintain our cognitive function, but also enhance and grow it as we go.

Want to know more from today’s featured expert?

You might enjoy her book, “Smarter Tomorrow”, which we reviewed back in March

Share This Post

-

Decoding Hormone Balancing in Ads

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Time!

This is the bit whereby each week, we respond to subscriber questions/requests/etc

Have something you’d like to ask us, or ask us to look into? Hit reply to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom, and a Real Human™ will be glad to read it!

Q: As to specific health topics, I would love to see someone address all these Instagram ads targeted to women that claim “You only need to ‘balance your hormones’ to lose weight, get ripped, etc.” What does this mean? Which hormones are they all talking about? They all seem to be selling a workout program and/or supplements or something similar, as they are ads, after all. Is there any science behind this stuff or is it mostly hot air, as I suspect?

Thank you for asking this, as your question prompted yesterday’s main feature, What Does “Balancing Your Hormones” Even Mean?

That’s a great suggestion also about addressing ads (and goes for health-related things in general, not just hormonal stuff) and examining their claims, what they mean, how they work (if they work!), and what’s “technically true but may

be misleading* cause confusion”*We don’t want companies to sue us, of course.

Only, we’re going to need your help for this one, subscribers!

See, here at 10almonds we practice what we preach. We limit screen time, we focus on our work when working, and simply put, we don’t see as many ads as our thousands of subscribers do. Also, ads tend to be targeted to the individual, and often vary from country to country, so chances are good that we’re not seeing the same ads that you’re seeing.

So, how about we pull together as a bit of a 10almonds community project?

- Step 1: add our email address to your contacts list, if you haven’t already

- Step 2: When you see an ad you’re curious about, select “share” (there is usually an option to share ads, but if not, feel free to screenshot or such)

- Step 3: Send the ad to us by email

We’ll do the rest! Whenever we have enough ads to review, we’ll do a special on the topic.

We will categorically not be able to do this without you, so please do join in—Many thanks in advance!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Marrakesh Sorghum Salad

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As the name suggests, it’s a Maghreb dish today! Using sorghum, a naturally gluten-free whole grain with a stack of vitamins and minerals. This salad also comes with fruit and nuts (apricots and almonds; a heavenly combination for both taste and nutrients) as well as greens, herbs, and spices.

Note: to keep things simple today, we’ve listed ras el-hanout as one ingredient. If you’re unfamiliar, it’s a spice blend; you can probably buy a version locally, but you might as well know how to make it yourself—so here’s our recipe for that!

You will need

- 1½ cups sorghum, soaked overnight in water (if you can’t find it locally, you can order it online (here’s an example product on Amazon), or substitute quinoa) and if you have time, soaked overnight and then kept in a jar with just a little moisture for a few days until they begin to sprout—this will be best of all. But if you don’t have time, don’t worry about it; overnight soaking is sufficient already.

- 1 carrot, grated

- ½ cup chopped parsley

- 1 tbsp apple cider vinegar

- ½ tbsp chopped chives

- 2 tbsp ras el-hanout

- 3 cloves garlic, crushed

- 2 tbsp almond butter

- 1 tbsp lemon juice

- 1 tsp white miso paste

- ½ cup sliced almonds

- 4 fresh apricots, pitted and cut into wedges

- 1 cup mint leaves, chopped

- To serve: your choice of salad greens; we suggest chopped romaine lettuce and rocket

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Cook the sorghum, which means boiling it for about 45 minutes, or 30 in a pressure cooker. If unsure, err on the side of cooking longer—even up to an hour will be totally fine. You have a lot of wiggle room, and will soon get used to how long it takes with your device/setup. Drain the cooked sorghum, and set it aside to cool. If you’re entertaining, we recommend doing this part the day before and keeping it in the fridge.

2) When it’s cool, add the carrot, the parsley, the chives, the vinegar, and 1 tbsp of the ras el-hanout. Toss gently but thoroughly to combine.

3) Make the dressing, which means putting ¼ cup water into a blender with the other 1 tbsp of the ras el-hanout, the garlic, the almond butter, the lemon juice, and the miso paste. Blend until smooth.

4) Assemble the salad, which means adding the dressing to sorghum-and-ingredients bowl, along with the almonds, apricots, and mint leaves. Toss gently, but sufficiently that everything is coated.

5) Serve on a bed of salad greens.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet ← including an anti-inflammatory version, which is functionally what we’re doing today. As an aside when people hear “Mediterranean” they often think “Italy and Greece”. Which, sure, but N. Africa (and thus Maghreb cuisine) is also very much Mediterranean, and it shows!

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Brain Food? The Eyes Have It!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

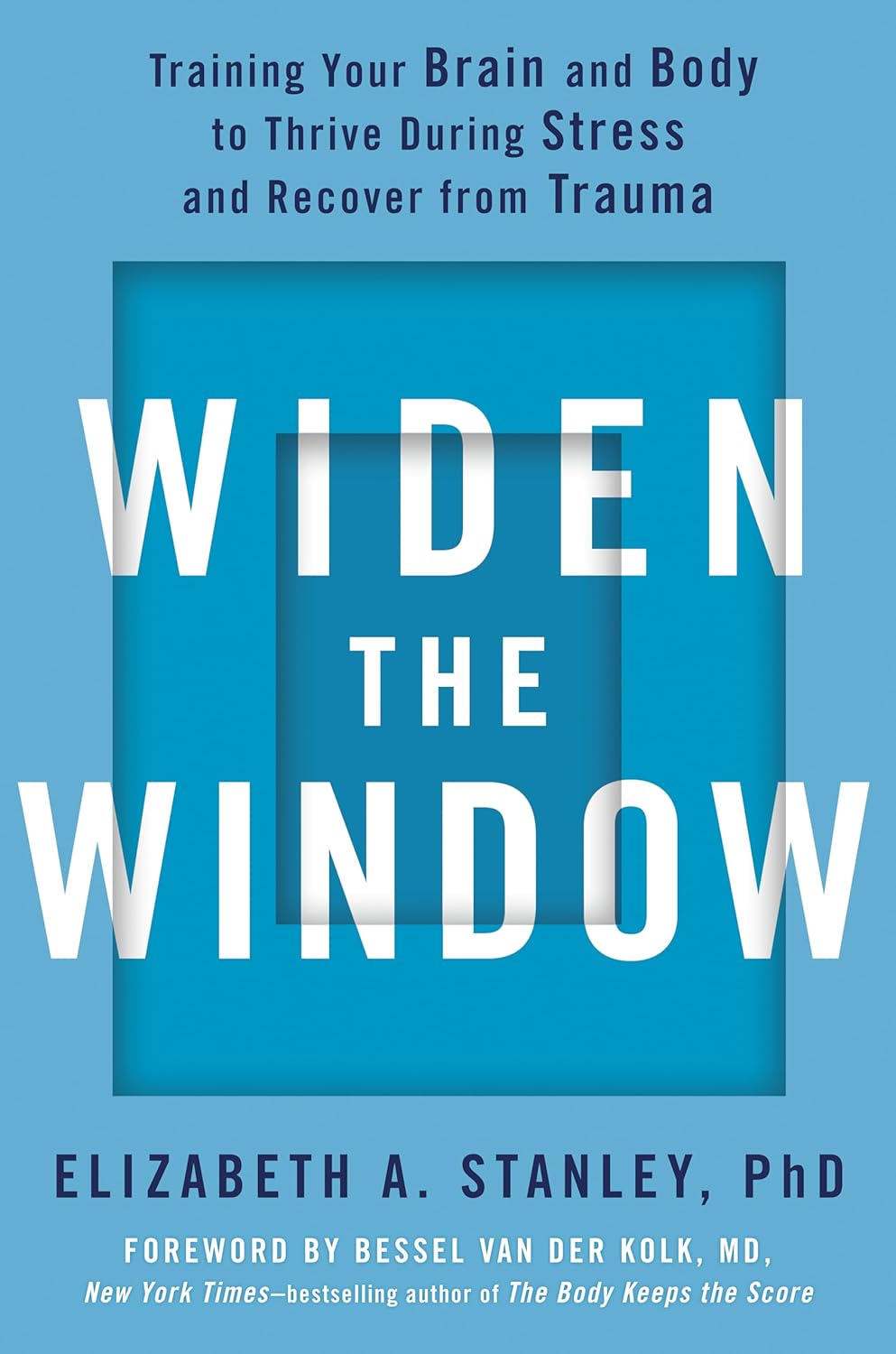

Widen the Window – by Dr. Elizabeth Stanley

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Firstly, about the title… That “window” that the author bids us “widen” is not a flowery metaphor, but rather, is referring to the window of exhibited resilience to stress/trauma; the “window” in question looks like an “inverted U” bell-curve on the graph.

In other words: Dr. Stanley’s main premise here is that we respond best to moderate stress (i.e: in that window, the area under the curve!), but if there is too little or too much, we don’t do so well. The key, she argues, is widening that middle part (expanding the area under the curve) in which we perform optimally. That way, we can still function in a motivated fashion without extrinsic threats, and we also don’t collapse under the weight of overwhelm, either.

The main strength of this book, however, lies in its practical exercises to accomplish that—and more.

“And more”, because the subtitle also promised recovery from trauma, and the author delivers in that regard too. In this case, it’s about widening that same window, but this time to allow one’s parasympathetic nervous system to recognize that the traumatic event is behind us, and no longer a threat; we are safe now.

Bottom line: if you would like to respond better to stress, and/or recover from trauma, this book is a very good tool.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

STI rates are increasing among midlife and older adults. We need to talk about it

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Globally, the rates of common sexually transmissible infections (STIs) are increasing among people aged over 50. In some cases, rates are rising faster than among younger people.

Recent data from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that, among people aged 55 and older, rates of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, two of the most common STIs, more than doubled between 2012 and 2022.

Australian STI surveillance data has reflected similar trends. Between 2013 and 2022, there was a steady increase in diagnoses of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis among people aged 40 and older. For example, there were 5,883 notifications of chlamydia in Australians 40 plus in 2013, compared with 10,263 in 2022.

A 2020 study of Australian women also showed that, between 2000 and 2018, there was a sharper increase in STI diagnoses among women aged 55–74 than among younger women.

While the overall rate of common STIs is highest among young adults, the significant increase in STI diagnoses among midlife and older adults suggests we need to pay more attention to sexual health across the life course.

Fit Ztudio/Shutterstock Why are STI rates rising among older adults?

STI rates are increasing globally for all age groups, and an increase among midlife and older people is in line with this trend.

However, increases of STIs among older people are likely due to a combination of changing sex and relationship practices and hidden sexual health needs among this group.

The “boomer” generation came of age in the 60s and 70s. They are the generation of free love and their attitude to sex, even as they age, is quite different to that of generations before them.

Given the median age of divorce in Australia is now over 43, and the internet has ushered in new opportunities for post-separation dating, it’s not surprising that midlife and older adults are exploring new sexual practices or finding multiple sexual partners.

People may start new relationships later in life. Tint Media/Shutterstock It’s also possible midlife and older people have not had exposure to sexual health education in school or do not relate to current safe sex messages, which tend to be directed toward young people. Condoms may therefore seem unnecessary for people who aren’t trying to avoid pregnancy. Older people may also lack confidence negotiating safe sex or accessing STI screening.

Hidden sexual health needs

In contemporary life, the sex lives of older adults are largely invisible. Ageing and older bodies are often associated with loss of power and desirability, reflected in the stereotype of older people as asexual and in derogatory jokes about older people having sex.

With some exceptions, we see few positive representations of older sexual bodies in film or television.

Older people’s sexuality is also largely invisible in public policy. In a review of Australian policy relating to sexual and reproductive health, researchers found midlife and older adults were rarely mentioned.

Sexual health policy generally targets groups with the highest STI rates, which excludes most older people. As midlife and older adults are beyond childbearing years, they also do not feature in reproductive health policy. This means there is a general absence of any policy related to sex or sexual health among midlife or older adults.

Added to this, sexual health policy tends to be focused on risk rather than sexual wellbeing. Sexual wellbeing, including freedom and capacity to pursue pleasurable sexual experiences, is strongly associated with overall health and quality of life for adults of all ages. Including sexual wellbeing as a policy priority would enable a focus on safe and respectful sex and relationships across the adult life course.

Without this priority, we have limited knowledge about what supports sexual wellbeing as people age and limited funding for initiatives to engage with midlife or older adults on these issues.

Midlife and older adults may have limited knowledge about STIs. Southworks/Shutterstock How can we support sexual health and wellbeing for older adults?

Most STIs are easily treatable. Serious complications can occur, however, when STIs are undiagnosed and untreated over a long period. Untreated STIs can also be passed on to others.

Late diagnosis is not uncommon as some STIs can have no symptoms and many people don’t routinely screen for STIs. Older, heterosexual adults are, in general, less likely than other groups to seek regular STI screening.

For midlife or older adults, STIs may also be diagnosed late because some doctors do not initiate testing due to concerns they will cause offence or because they assume STI risk among older people is negligible.

Many doctors are reluctant to discuss sexual health with their older patients unless the patient explicitly raises the topic. However, older people can be embarrassed or feel awkward raising matters of sex.

Resources for health-care providers and patients to facilitate conversations about sexual health and STI screening with older patients would be a good first step.

To address rising rates of STIs among midlife and older adults, we also need to ensure sexual health promotion is targeted toward these age groups and improve accessibility of clinical services.

More broadly, it’s important to consider ways to ensure sexual wellbeing is prioritised in policy and practice related to midlife and older adulthood.

A comprehensive approach to older people’s sexual health, that explicitly places value on the significance of sex and intimacy in people’s lives, will enhance our ability to more effectively respond to sexual health and STI prevention across the life course.

Jennifer Power, Associate Professor and Principal Research Fellow, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: