Qigong: A Breath Of Fresh Air?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Qigong: Breathing Is Good (Magic Remains Unverified)

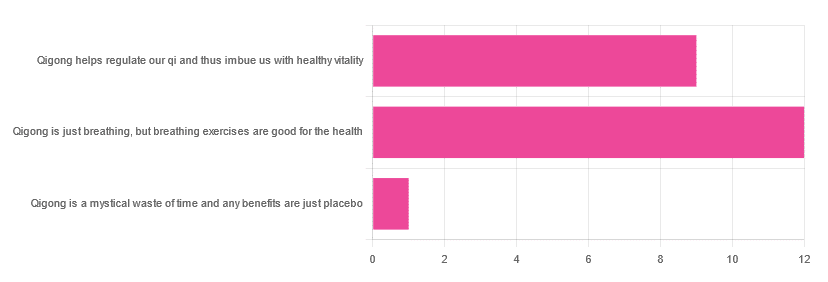

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinions of qigong, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 55% said “Qigong is just breathing, but breathing exercises are good for the health”

- About 41% said “Qigong helps regulate our qi and thus imbue us with healthy vitality”

- One (1) person said “Qigong is a mystical waste of time and any benefits are just placebo”

The sample size was a little low for this one, but the results were quite clearly favorable, one way or another.

So what does the science say?

Qigong is just breathing: True or False?

True or False, depending on how we want to define it—because qigong ranges in its presentation from indeed “just breathing exercises”, to “breathing exercises with visualization” to “special breathing exercises with visualization that have to be exactly this way, with these hand and sometimes body movements also, which also must be just right”, to far more complex definitions that involve qi by various mystical definitions, and/or an appeal to a scientific analog of qi; often some kind of bioelectrical field or such.

There is, it must be said, no good quality evidence for the existence of qi.

Writer’s note, lest 41% of you want my head now: I’ve been practicing qigong and related arts for about 30 years and find such to be of great merit. This personal experience and understanding does not, however, change the state of affairs when it comes to the availability (or rather, the lack) of high quality clinical evidence to point to.

Which is not to say there is no clinical evidence, for example:

Acute Physiological and Psychological Effects of Qigong Exercise in Older Practitioners

…found that qigong indeed increased meridian electrical conductance!

Except… Electrical conductance is measured with galvanic skin responses, which increase with sweat. But don’t worry, to control for that, they asked participants to dry themselves with a towel. Unfortunately, this overlooks the fact that a) more sweat can come where that came from, because the body will continue until it is satisfied of adequate homeostasis, and b) drying oneself with a towel will remove the moisture better than it’ll remove the salts from the skin—bearing in mind that it’s mostly the salts, rather than the moisture itself, that improve the conductivity (pure distilled water does conduct electricity, but not very well).

In other words, this was shoddy methodology. How did it pass peer review? Well, here’s an insight into that journal’s peer review process…

❝The peer-review system of EBCAM is farcical: potential authors who send their submissions to EBCAM are invited to suggest their preferred reviewers who subsequently are almost invariably appointed to do the job. It goes without saying that such a system is prone to all sorts of serious failures; in fact, this is not peer-review at all, in my opinion, it is an unethical sham.❞

~ Dr. Edzard Ernst, a founding editor of EBCAM (he since left, and decries what has happened to it since)

One of the other key problems is: how does one test qigong against placebo?

Scientists have looked into this question, and their answers have thus far been unsatisfying, and generally to the tune of the true-but-unhelpful statement that “future research needs to be better”:

Problems of scientific methodology related to placebo control in Qigong studies: A systematic review

Most studies into qigong are interventional studies, that is to say, they measure people’s metrics (for example, blood pressure, heart rate, maybe immune function biomarkers, sleep quality metrics of various kinds, subjective reports of stress levels, physical biomarkers of stress levels, things like that), then do a course of qigong (perhaps 6 weeks, for example), then measure them again, and see if the course of qigong improved things.

This almost always results in an improvement when looking at the before-and-after, but it says nothing for whether the benefits were purely placebo.

We did find one study that claimed to be placebo-controlled:

…but upon reading the paper itself carefully, it turned out that while the experimental group did qigong, the control group did a reading exercise. Which is… Saying how well qigong performs vs reading (qigong did outperform reading, for the record), but nothing for how well it performs vs placebo, because reading isn’t a remotely credible placebo.

See also: Placebo Effect: Making Things Work Since… Well, A Very Long Time Ago ← this one explains a lot about how placebo effect does work

Qigong is a mystical waste of time: True or False?

False! This one we can answer easily. Interventional studies invariably find it does help, and the fact remains that even if placebo is its primary mechanism of action, it is of benefit and therefore not a waste of time.

Which is not to say that placebo is its only, or even necessarily primary, mechanism of action.

Even from a purely empirical evidence-based medicine point of view, qigong is at the very least breathing exercises plus (usually) some low-impact body movement. Those are already two things that can be looked at, mechanistic processes pointed to, and declarations confidently made of “this is an activity that’s beneficial for health”.

See for example:

- Effects of Qigong practice in office workers with chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized control trial

- Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Infection in Older Adults

- Impact of Medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial

…and those are all from respectable journals with meaningful peer review processes.

None of them are placebo-controlled, because there is no real option of “and group B will only be tricked into believing they are doing deep breathing exercises with low-impact movements”; that’s impossible.

But! They each show how doing qigong reliably outperforms not doing qigong for various measurable metrics of health.

And, we chose examples with physical symptoms and where possible empirically measurable outcomes (such as COVID-19 infection levels, or inflammatory responses); there are reams of studies showings qigong improves purely subjective wellbeing—but the latter could probably be claimed for any enjoyable activity, whereas changes in inflammatory biomarkers, not such much.

In short: for most people, it indeed reliably helps with many things. And importantly, it has no particular risks associated with it, and it’s almost universally framed as a complementary therapy rather than an alternative therapy.

This is critical, because it means that whereas someone may hold off on taking evidence-based medicines while trying out (for example) homeopathy, few people are likely to hold off on other treatments while trying out qigong—since it’s being viewed as a helper rather than a Hail-Mary.

Want to read more about qigong?

Here’s the NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has to say. It cites a lot of poor quality science, but it does mention when the science it’s citing is of poor quality, and over all gives quite a rounded view:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How To Avoid Carer Burnout (Without Dropping Care)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How To Avoid Carer Burnout

Sometimes in life we find ourselves in a caregiving role.

Maybe we chose it. For example, by becoming a professional carer, or even just by being a parent.

Oftentimes we didn’t. Sometimes because our own parents now need care from us, or because a partner becomes disabled.

Philosophical note: an argument could be made for that latter also having been a pre-emptive choice; we probably at some point said words to the effect of “in sickness and in health”, hopefully with free will, and hopefully meant it. And of course, sometimes we enter into a relationship with someone who is already disabled.

But, we are not a philosophy publication, and will henceforth keep to the practicalities.

First: are you the right person?

Sometimes, a caregiving role might fall upon you unasked-for, and it’s worth considering whether you are really up for it. Are you in a position to be that caregiver? Do you want to be that caregiver?

It may be that you do, and would actively fight off anyone or anything that tried to stop you. If so, great, now you only need to make sure that you are actually in a position to provide the care in question.

It may be that you do want to, but your circumstances don’t allow you to do as good a job of it as you’d like, or it means you have to drop other responsibilities, or you need extra help. We’ll cover these things later.

It may be that you don’t want to, but you feel obliged, or “have to”. If that’s the case, it will be better for everyone if you acknowledge that, and find someone else to do it. Nobody wants to feel a burden, and nobody wants someone providing care to be resentful of that. The result of such is two people being miserable; that’s not good for anyone. Better to give the job to someone who actually wants to (a professional, if necessary).

So, be honest (first with yourself, then with whoever may be necessary) about your own preferences and situation, and take steps to ensure you’re only in a caregiving role that you have the means and the will to provide.

Second: are you out of your depth?

Some people have had a life that’s prepared them for being a carer. Maybe they worked in the caring profession, maybe they have always been the family caregiver for one reason or another.

Yet, even if that describes you… Sometimes someone’s care needs may be beyond your abilities. After all, not all care needs are equal, and someone’s condition can (and more often than not, will) deteriorate.

So, learn. Learn about the person’s condition(s), medications, medical equipment, etc. If you can, take courses and such. The more you invest in your own development in this regard, the more easily you will handle the care, and the less it will take out of you.

And, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Maybe the person knows their condition better than you, and certainly there’s a good chance they know their care needs best. And certainly, there are always professionals that can be contacted to ask for advice.

Sometimes, a team effort may be required, and there’s no shame in that either. Whether it means enlisting help from family/friends or professionals, sometimes “many hands make light work”.

Check out: Caregiver Action Network: Organizations Near Me

A very good resource-hub for help, advice, & community

Third: put your own oxygen mask on first

Like the advice to put on one’s own oxygen mask first before helping others (in the event of a cabin depressurization in an airplane), the rationale is the same here. You can’t help others if you are running on empty yourself.

As a carer, sometimes you may have to put someone else’s needs above yours, both in general and in the moment. But, you do have needs too, and cannot neglect them (for long).

One sleepless night looking after someone else is… a small sacrifice for a loved one, perhaps. But several in a row starts to become unsustainable.

Sometimes it will be necessary to do the best you can, and accept that you cannot do everything all the time.

There’s a saying amongst engineers that applies here too: “if you don’t schedule time for maintenance, your equipment will schedule it for you”.

In other words: if you don’t give your body rest, your body will break down and oblige you to rest. Please be aware this goes for mental effort too; your brain is just another organ.

So, plan ahead, schedule breaks, find someone to take over, set up your cared-for-person with the resources to care for themself as well as possible (do this anyway, of course—independence is generally good so far as it’s possible), and make the time/effort to get you what you need for you. Sleep, distraction, a change of scenery, whatever it may be.

Lastly: what if it’s you?

If you’re reading this and you’re the person who has the higher care needs, then firstly:all strength to you. You have the hardest job here; let’s not forget that.

About that independence: well-intentioned people may forget that, so don’t be afraid to remind them when “I would prefer to do that myself”. Maintaining independence is generally good for the health, even if sometimes it is more work for all concerned than someone else doing it for you. The goal, after all, is your wellbeing, so this shouldn’t be cast aside lightly.

On the flipside: you don’t have to be strong all the time; nobody should.

Being disabled can also be quite isolating (this is probably not a revelation to you), so if you can find community with other people with the same or similar condition(s), even if it’s just online, that can go a very, very long way to making things easier. Both practically, in terms of sharing tips, and psychologically, in terms of just not feeling alone.

See also: How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

Share This Post

-

Eating For Energy (In Ways That Actually Work)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Snacks & Hacks: The Real Energy Boosters

Declining energy levels are a common complaint of people getting older, and this specific kind of “getting older” is starting earlier and earlier (even Gen-Z are already getting in line for this one). For people of all ages, however, diet is often a large part of the issue.

The problem:

It can sometimes seem, when it comes to food and energy levels, that we have a choice:

- Don’t eat (energy levels decline)

- Eat quick-release energy snacks (energy spikes and crashes)

- Eat slow-release energy meals (oh hi, post-dinner slump)

But, this minefield can be avoided! Advice follows…

Skip the quasi-injectables

Anything the supermarket recommends for rapid energy can be immediately thrown out (e.g. sugary energy drinks, glucose tablets, and the like).

Same goes for candy of most sorts (if the first ingredient is sugar, it’s not good for your energy levels).

Unless you are diabetic and need an emergency option to keep with you in case of a hypo, the above things have no place on a healthy shopping list.

Aside from that, if you have been leaning on these heavily, you might want to check out yesterday’s main feature:

The Not-So-Sweet Science Of Sugar Addiction

…and if your knee-jerk response is “I’m not addicted; I just enjoy…” then ok, test that! Skip it for this month.

- If you succeed, you’ll be in better health.

- If you don’t, you’ll be aware of something that might benefit from more attention.

Fruit and nuts are your best friends

Unless you are allergic, in which case, obviously skip your allergen(s).

But for most of us, we were born to eat fruit and nuts. Literally, those two things are amongst the oldest and most well-established parts of human diet, which means that our bodies have had a very long time to evolve the perfect fruit-and-nut-enjoying abilities, and reap the nutritional benefits.

Nuts are high in fat (healthy fats) and that fat is a great source of energy’s easy for the body to get from the food, and/but doesn’t result in blood sugar spikes (and thus crashes) because, well, it’s not a sugar.

See also: Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Fruit is high in sugars, and/but high in fiber that slows the absorption into a nice gentle curve, and also contains highly bioavailable vitamins to perk you up and polyphenols to take care of your long-term health too.

Be warned though: fruit juice does not work the same as actual fruit; because the fiber has been stripped and it’s a liquid, those sugars are zipping straight in exactly the same as a sugary energy drink.

See also: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Slow release carbs yes, but…

Eating a bowl of wholegrain pasta is great if you don’t have to do anything much immediately afterwards, but it won’t brighten your immediately available energy much—on the contrary, energy will be being used for digestion for a while.

So if you want to eat slow-release carbs, make it a smaller portion of something more-nutrient dense, like oats or lentils. This way, the metabolic load will be smaller (because the portion was smaller) but the higher protein content will prompt satiety sooner (so you addressed your hunger with a smaller portion) and the iron and B vitamins will be good for your energy too.

See also: Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

Animal, vegetable, or mineral?

At the mention of iron and B vitamins, you might be thinking about various animal products that might work too.

If you are vegetarian or vegan: stick to that; it’s what your gut microbiome is used to now, and putting an animal product in will likely make you feel ill.

If you have them in your diet already, here’s a quick rundown of how broad categories of animal product work (or not) for energy:

- Meat: nope. Well, the fat, if applicable, will give you some energy, but less than you need just to digest the meat. This, by the way, is a likely part of why the paleo diet is good for short term weight loss. But it’s not very healthy.

- Fish: healthier than the above, but for energy purposes, just the same.

- Dairy: high-fat dairy, such as cream and butter, are good sources of quick energy. Be aware if they contain lactose though, that this is a sugar and can be back to spiking blood sugars.

- As an aside for diabetics: this is why milk can be quite good for correcting a hypo: the lactose provides immediate sugar, and the fat keeps it more balanced afterwards

- Eggs: again the fat is a good source of quick energy, and the protein is easier to digest than that of meat (after all, egg protein is literally made to be consumed by an embryo, while meat protein is made to be a functional muscle of an animal), so the metabolic load isn’t too strenuous. Assuming you’re doing a moderate consumption (under 3 eggs per day) and not Sylvester Stallone-style 12-egg smoothies, you’re good to go.

See also: Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy?

…and while you’re at it, check out:

Eggs: Nutritional Powerhouse

or Heart-Health Timebomb?(spoiler: it’s the former; the title was because it was a mythbusting edition)

Hydration considerations

Lastly, food that is hydrating will be more energizing than food that is not, so how does your snack/meal rank on a scale of watermelon to saltines?

You may be thinking: “But you said to eat nuts! They’re not hydrating at all!”, in which case, indeed, drink water with them, or better yet, enjoy them alongside fruit (hydration from food is better than hydration from drinking water).

And as for those saltines? Salt is not your friend (unless you are low on sodium, because then that can sap your energy)

How to tell if you are low on sodium: put a little bit (e.g. ¼ tsp) of salt into a teaspoon and taste it; does it taste unpleasantly salty? If not, you were low on sodium. Have a little more at five minute intervals, until it tastes unpleasantly salty. Alternatively have a healthy snack that nonetheless contains a little salt.

If you otherwise eat salty food as an energy-giving snack, you risk becoming dehydrated and bloated, neither of which are energizing conditions.

Dehydrated and bloated at once? Yes, the two often come together, even though it usually doesn’t feel like it. Basically, if we consume too much salty food, our homeostatic system goes into overdrive to try to fix it, borrows a portion of our body’s water reserves to save us from the salt, and leaves us dehydrated, bloated, and sluggish.

For more on salt in general, check out:

How Too Much Salt Can Lead To Organ Failure: Lesser-Known Salt Health Risks

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Sesame Chocolate Fudge

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you’d like a sweet treat without skyrocketing your blood sugars with, well, rocket fuel… Today’s recipe can help you enjoy a taste of decadence that’s not bad for your blood sugars, and good for your heart and brain.

You will need

- ½ cup sesame seeds

- ¼ cup cocoa powder

- 3 tbsp maple syrup

- 1 tbsp coconut oil (plus a little extra for the pan)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Lightly toast the sesame seeds in a pan until golden brown. Remove from the heat and allow to cool.

2) Put them in a food processor, and blend on full speed until they start to form a dough-like mixture. This may take a few minutes, so be patient. We recommend doing it in 30-second sessions with a 30-second rest between them, to avoiding overheating the motor.

3) Add the rest of the ingredients and blend to combine thoroughly—this should go easily now and only take 10 seconds or so, but judge it by eye.

4) Grease an 8″ square baking tin with a little coconut oil, and add the mixture, patting it down to fill the tin, making sure it is well-compressed.

5) Allow to chill in the fridge for 6 hours, until firm.

6) Turn the fudge out onto a chopping board, and cut into the size squares you want. Serve, or store in the fridge until ready to serve.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Tasty Polyphenols For Your Heart & Brain

- Cacao vs Carob – Which is Healthier?

- Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Brown Rice vs Wild Rice – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing brown rice to wild rice, we picked the wild.

Why?

It’s close! But there are important distinctions.

First let’s clarify: despite the name and appearance, wild rice is botanically quite different from rice per se; it’s not the same species, it’s not even the same genus, though it is the same umbrella family. In other words, they’re about as closely related as humans and gorillas are to each other.

In terms of macros, wild rice has considerably more protein and a little more fiber, for slightly lower carbs.

Notably, however, wild rice’s carbs are a close-to-even mix of sucrose, fructose, and glucose, while brown rice’s carbs are 99% starch. Given the carb to fiber ratio, it’s worth noting that wild rice also has lower net carbs, and the lower glycemic index.

In the category of vitamins, wild rice leads with more of vitamins A, B2, B9, E, K, and choline. In contrast, brown rice has more of vitamins B1, B3, and B5. So, a moderate win for wild rice.

When it comes to minerals, brown rice finally gets a tally in its favor, even if only slightly: brown rice has more magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, and selenium, while wild rice has more copper, potassium, and zinc. They’re equal in calcium and iron, by the way. Still, this category stands as a 4:3 win for brown rice.

Adding up the categories makes a modest win for wild rice, and additionally, if we had to consider one of these things more important than the others, it’d be wild rice being higher in fiber and protein and lower in total carbs and net carbs.

Still, enjoy either or both, per your preference!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Brown Rice Protein: Strengths & Weaknesses

- Rice vs Buckwheat – Which is Healthier? ← it’s worth noting, by the way, that buckwheat is so unrelated from wheat that it’s not even the same family of plants. They are about as closely related as a lion and a lionfish are to each other.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Red Light, Go!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Casting Yourself In A Healthier Light

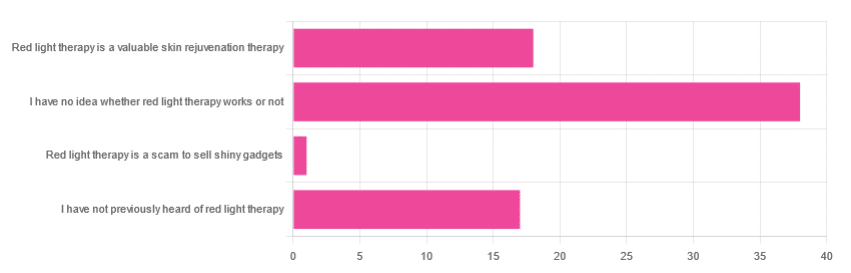

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinion of red light therapy (henceforth: RLT), and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 51% said “I have no idea whether light therapy works or not”

- About 24% said “Red light therapy is a valuable skin rejuvenation therapy”

- About 23% said “I have not previously heard of red light therapy”

- One (1) person said: “Red light therapy is a scam to sell shiny gadgets”

A number of subscribers wrote with personal anecdotes of using red light therapy to beneficial effect, for example:

❝My husband used red light therapy after surgery on his hand. It did seem to speed healing of the incision and there is very minimal scarring. I would like to know if the red light really helped or if he was just lucky❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

And one wrote to report having observed mixed results amongst friends, per:

❝Some people it works, others I’ve seen it breaks them out❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

So, what does the science say?

RLT rejuvenates skin, insofar as it reduces wrinkles and fine lines: True or False?

True! This one’s pretty clear-cut, so we’ll just give one example study of many, which found:

❝The treated subjects experienced significantly improved skin complexion and skin feeling, profilometrically assessed skin roughness, and ultrasonographically measured collagen density.

The blinded clinical evaluation of photographs confirmed significant improvement in the intervention groups compared with the control❞

~ Dr. Alexander Wunsch & Dr. Karsten Matuschka

RLT helps speed up healing of wounds: True or False?

True! There is less science for this than the above claim, but the studies that have been done are quite compelling, for example this NASA technology study found that…

❝LED produced improvement of greater than 40% in musculoskeletal training injuries in Navy SEAL team members, and decreased wound healing time in crew members aboard a U.S. Naval submarine.❞

Read more: Effect of NASA light-emitting diode irradiation on wound healing

RLT’s benefits are only skin-deep: True or False?

False, probably, but we’d love to see more science for this, to be sure.

However, it does look like wavelengths in the near-infrared spectrum reduce the abnormal tau protein and neurofibrillary tangles associated with Alzheimer’s disease, resulting in increased blood flow to the brain, and a decrease in neuroinflammation:

Therapeutic Potential of Photobiomodulation In Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review

Would you like to try RLT for yourself?

There are some contraindications, for example:

- if you have photosensitivity (for obvious reasons)

- if you have Lupus (mostly because of the above)

- if you have hyperthyroidism (because if you use RLT to your neck as well as face, it may help stimulate thyroid function, which in your case is not what you want)

As ever, please check with your own doctor if you’re not completely sure; we can’t cover all bases here, and cannot speak for your individual circumstances.

For most people though, it’s very safe, and if you’d like to try it, here’s an example product on Amazon, and by all means do read reviews and shop around for the ideal device for you

Take care! 😎

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Polyphenol Paprika Pepper Penne

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one’s easier to promptly prepare than it is to pronounce unprepared! Ok, enough alliteration: this dish is as full of flavor as it is full of antioxidants, and it’s great for digestive health and heart health too.

You will need

- 4 large red bell peppers, diced

- 2 red onions, roughly chopped

- 1 bulb garlic, finely chopped

- 2 cups cherry tomatoes, halved

- 10oz wholemeal penne pasta

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tbsp smoked paprika

- 1 tbsp black pepper

- Extra virgin olive oil for drizzling

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 200℃ / 400℉ / Gas mark 6

2) Put the vegetables in a roasting tin; drizzle with oil, sprinkle with the seasonings (nooch, paprika, black pepper), stir well to mix and distribute the seasonings evenly, and roast for 20–25 minutes, stirring/turning occasionally. When the edges begin to caramelize, turn off the heat, but leave to keep warm.

3) Cook the penne al dente (this should take 7–8 minutes in boiling salted water). Rinse in cold water, then pass a kettle of hot water over them to reheat. This process removed starch and lowered the glycemic index, before reheating the pasta so that it’s hot to serve.

4) Place the roasted vegetables in a food processor and blitz for just a few seconds. You want to produce a very chunky sauce—but not just chunks or just sauce.

5) Combine the sauce and pasta to serve immediately.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Which Bell Peppers To Pick? A Spectrum Of Specialties ← note how red bell peppers are perfect for this, as their lycopene quadruples in bioavailability when cooked

- Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

- The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

- What Matters Most For Your Heart? Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: