Brown Rice Protein: Strengths & Weaknesses

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I had a friend mention that recent research showed Brown Rice Protein Powder can be bad for you, possibly impacting your nutrient absorption. Is this true? I’ve been using it given it’s one of the few plant-based proteins with a full essential amino acid profile!❞

Firstly: we couldn’t find anything to corroborate the “brown rice protein powder [adversely] impacts nutrient absorption” idea, but we suspect that the reason for this belief is: brown rice (not brown rice protein powder) contains phytic acid, which is something of an antinutrient, in that it indeed reduces absorption of various other nutrients.

However, two things are important to note here:

- the phytic acid is found in whole grains, not in protein isolates as found in brown rice protein powder. The protein isolates contain protein… Isolated. No phytates!

- even in the case of eating whole grain rice, the phytic acid content is greatly reduced by two things: soaking and heating (especially if those two things are combined) ← doing this the way described results in bioavailability of nutrients that’s even better than if there were just no phytic acid, albeit it requires you having the time to soak, and do so at temperature.

tl;dr = no, it’s not true, unless there truly is some groundbreaking new research we couldn’t find—it was almost certainly a case of an understandable confusion about phytic acid.

Your question does give us one other thing to mention though:

Brown rice indeed technically contains all 9 essential amino acids, but it’s very low in several of them, most notably lysine.

However, if you use our Tasty Versatile Rice Recipe, the chia seeds we added to the rice have 100x the lysine that brown rice does, and the black pepper also boosts nutrient absorption.

Because your brown rice protein powder is a rice protein powder and not simply rice, it’s possible that they’ve tweaked it to overcome rice’s amino acid deficiencies. But, if you’re looking for a plant-based protein powder that is definitely a complete protein, soy is a very good option assuming you’re not allergic to that:

Amino Acid Compositions Of Soy Protein Isolate

If you’re wondering where to get it, you can see examples of them next to each other on Amazon here:

Brown Rice Protein Powder | Soy Protein Isolate Powder

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Exercise That Protects Your Brain

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Neuroscientist In The Gym

This is Dr. Wendy Suzuki. She’s a neuroscientist, and an expert in the neurobiology of memory, as well as neuroplasticity, and the role of exercise in neuroprotection.

We’ve sneakily semi-featured her before when we shared her Big Think talk:

Brain Benefits In Three Months… Through Walking?

Today we’re going to expand on that a little!

A Quick Recap

To share the absolute key points of that already fairly streamlined rundown:

- Exercise boosts levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin (and, which wasn’t mentioned there, noradrenaline)

- These are responsible for motivation, happiness, and focus (amongst other things)

- Persistent exercise boosts certain regions of the brain in particular, most notably the pre-frontal cortex and the hippocampi*

- These are responsible for planning and memory (amongst other things)

Dr. Suzuki advocates for stepping up your exercise routine if you can, with more exercise generally being better than less (unless you have some special medical reason why that’s not the case for you).

*often referred to in the singular as the hippocampus, but you have one on each side of your brain (unless a serious accident/incident destroyed one, but you’ll know if that applies to you, unless you lost both, in which case you will not remember about it).

What kind(s) of workout?

While a varied workout is best for overall health, for these brain benefits specifically, what’s most important is that it raises your heart rate.

This is why in her Big Think talk we shared before, she talks about the benefits of taking a brisk walk daily. See also:

If that’s not your thing, though (and/or is for whatever reason an inaccessible form of exercise for you), there is almost certainly some kind of High Intensity Interval Training that is a possibility for you. That might sound intimidating, but if you have a bit of floor and can exercise for one minute at a time, then HIIT is an option for you:

How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body)

Dr. Suzuki herself is an ardent fan of “intenSati” which blends cardio workouts with yoga for holistic mind-and-body fitness. In fact, she loves it so much that she became a certified exercise instructor:

How much is enough?

It’s natural to want to know the minimum we can do to get results, but Dr. Suzuki would like us to bear in mind that when it comes to our time spent exercising, it’s not so much an expense of time as an investment in time:

❝Exercise is something that when you spend time on it, it will buy you time when you start to work❞

Read more: A Neuroscientist Experimented on Her Students and Found a Powerful Way to Improve Brain Function

Ok, but we really want to know how much!

Dr. Suzuki recommends at least three to four 30-minute exercise sessions per week.

Note: this adds up to less than the recommended 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week, but high-intensity exercise counts for twice the minutes for these purposes, e.g. 1 minute of high-intensity exercise is worth 2 minutes of moderate exercise.

How soon will we see benefits?

Benefits start immediately, but stack up cumulatively with continued long-term exercise:

❝My lab showed that a single workout can improve your ability to shift and focus attention, and that focus improvement will last for at least two hours. ❞

…which is a great start, but what’s more exciting is…

❝The more you’re working out, the bigger and stronger your hippocampus and prefrontal cortex gets. Why is that important?

Because the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus are the two areas that are most susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases and normal cognitive decline in aging. ❞

In other words, while improving your heart rate through regular exercise will help prevent neurodegeneration by the usual mechanism of reducing neuroinflammation… It’ll also build the parts of your brain most susceptible to decline, meaning that when/if decline sets in, it’ll take a lot longer to get to a critical level of degradation, because it had more to start with.

Read more:

Inspir Modern Senior Living | Dr. Wendy Suzuki Boosts Brain Health with Exercise

Want more from Dr. Suzuki?

You might enjoy her TED talk:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically

Prefer text? TED.com has a transcript for you

Prefer lots of text? You might like her book, which we haven’t reviewed yet but will soon:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

- Exercise boosts levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin (and, which wasn’t mentioned there, noradrenaline)

-

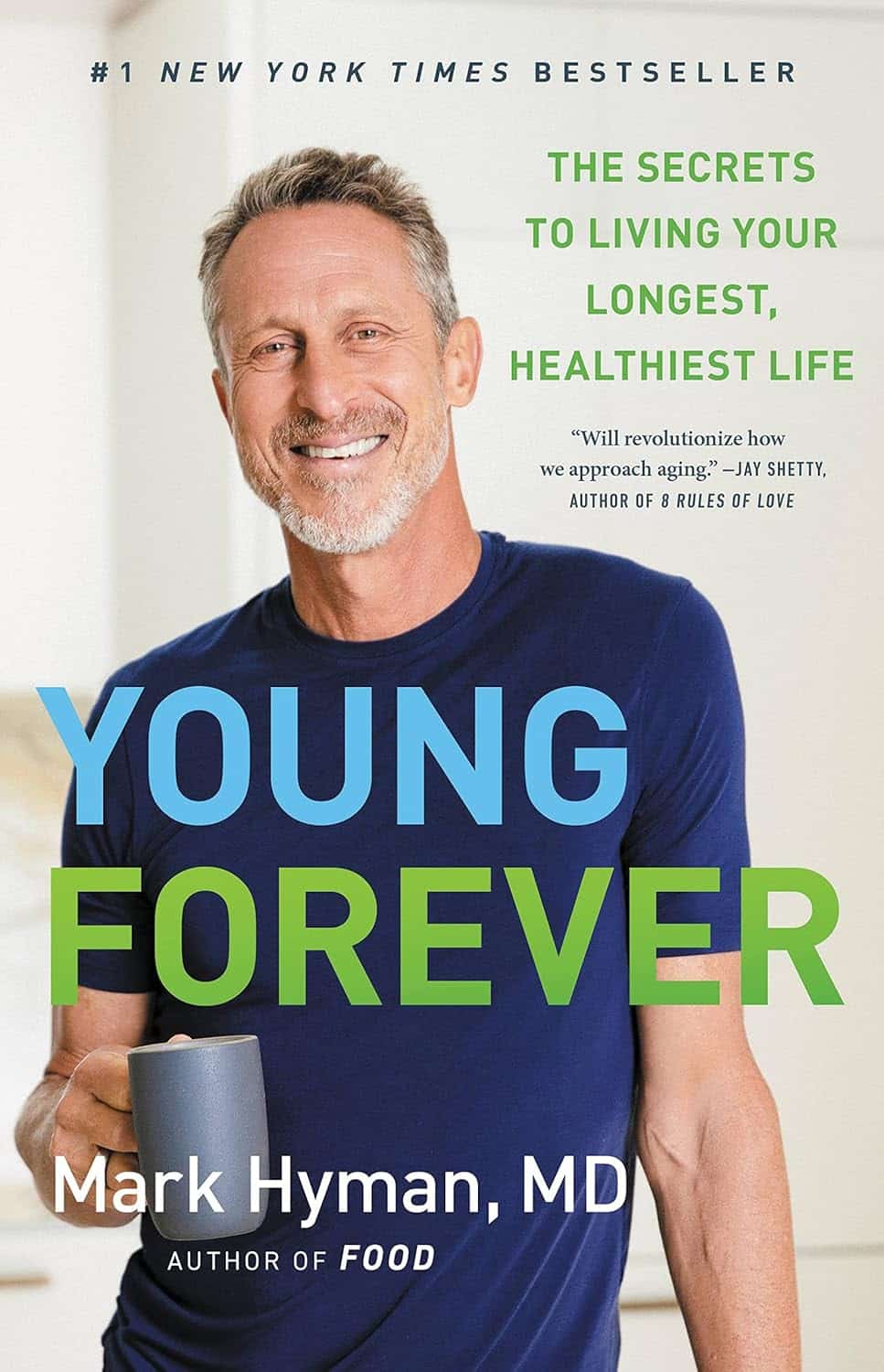

Young Forever – by Dr. Mark Hyman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A lot of work on the topic of aging looks at dealing with symptoms of aging, rather than the causes. And, that’s worthy too! Those symptoms often do need addressing. But this book is about treating the causes.

Dr. Hyman outlines:

- How and why we age

- The root causes of aging

- The ten hallmarks of aging

From there, we go on to learn about the foundations of longevity, and balancing our seven core biological systems:

- Nutrition, digestion, and the microbiome

- Immune and inflammatory system

- Cellular energy

- Biotransformation and elimination/detoxification*

- Hormones, neurotransmitters, and other signalling molecules

- Circulation and lymphatic flow

- Structural health, from muscle and bones to cells and tissues

*This isn’t about celery juice fasts and the like; this talking about the work your kidneys, liver, and other organs do

The book goes on to detail how, precisely, with practical actionable advices, to optimize and take care of each of those systems.

All in all: if you want a great foundational understanding of aging and how to slow it to increase your healthy lifespan, this is a very respectable option.

Click here to get your copy of “Young Forever” from Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

Shockingly, we’ve not previously covered this in a main feature here at 10almonds… Mostly we tend to focus on less well-known supplements. However, in this case, the supplement may be well known, while some of its benefits, we suspect, may come as a surprise.

So…

What is it?

In this case, it’s more of a “what are they?”, because omega-3 fatty acids come in multiple forms, most notably:

- Alpha-linoleic acid (ALA)

- Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)

- Docosahexanoic acid (DHA)

ALA is most readily found in certain seeds and nuts (chia seeds and walnuts are top contenders), while EPA and DHA are most readily found in certain fish (hence “cod liver oil” being a commonly available supplement, though actually cod aren’t even the best source—salmon and mackerel are better; cod is just cheaper to overfish, making it the cheaper supplement to manufacture).

Which of the three is best, or do we need them all?

There are two ways of looking at this:

- ALA is sufficient alone, because it is a precursor to EPA and DHA, meaning that the body will take ALA and convert it into EPA and DHA as required

- EPA and DHA are superior because they’re already in the forms the body will use, which makes them more efficient

As with most things in health, diversity is good, so you really can’t go wrong by getting some from each source.

Unless you have an allergy to fish or nuts, in which case, definitely avoid those!

What do omega-3 fatty acids do for us, according to actual research?

Against inflammation

Most people know it’s good for joints, as this is perhaps what it’s most marketed for. Indeed, it’s good against inflammation of the joints (and elsewhere), and autoimmune diseases in general. So this means it is indeed good against common forms of arthritis, amongst others:

Read: Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune disease

Against menstrual pain

Linked to the above-referenced anti-inflammatory effects, omega-3s were also found to be better than ibuprofen for the treatment of severe menstrual pain:

Don’t take our word for it: Comparison of the effect of fish oil and ibuprofen on treatment of severe pain in primary dysmenorrhea

Against cognitive decline

This one’s a heavy-hitter. It’s perhaps to be expected of something so good against inflammation (bearing in mind that, for example, a large part of Alzheimer’s is effectively a form of inflammation of the brain); as this one’s so important and such a clear benefit, here are three particularly illustrative studies:

- Inadequate supply of vitamins and DHA in the elderly: implications for brain aging and Alzheimer-type dementia

- Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study

- Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease

Against heart disease

The title says it all in this one:

But what about in patients who do have heart disease?

Mozaffarian and Wu did a huge meta-review of available evidence, and found that in fact, of all the studied heart-related effects, reducing mortality rate in cases of cardiovascular disease was the single most well-evidenced benefit:

How much should we take?

There’s quite a bit of science on this, and—which is unusual for something so well-studied—not a lot of consensus.

However, to summarize the position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics on dietary fatty acids for healthy adults, they recommend a minimum of 250–500 mg combined EPA and DHA each day for healthy adults. This can be obtained from about 8 ounces (230g) of fatty fish per week, for example.

If going for ALA, on the other hand, the recommendation becomes 1.1g/day for women or 1.6g/day for men.

Want to know how to get more from your diet?

Here’s a well-sourced article about different high-density dietary sources:

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Apples vs Dates – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apples to dates, we picked the dates.

Why?

Both have their strengths, but ultimatley, it wasn’t close:

In terms of macros, dates have more fiber and carbs, for an approximately equal glycemic index. Thus, we say dates win this category as the more nutritionally dense option.

In the category of vitamins, apples have more of vitamins A, C, and E, while dates have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, K, and choline. A clear win for dates.

When it comes to minerals, it’s even more one-sided: apples are not richer in any minerals, while dates have a lot more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. An overwhelming win for dates.

Of course, enjoy either or both (diversity is good), but if you want the most nutrients per bite, it’s dates.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Parsnips vs Potatoes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing parsnips to potatoes, we picked the parsnips.

Why?

To be more specific, we’re looking at russet potatoes, and in both cases we’re looking at cooked without fat or salt, skin on. In other words, the basic nutritional values of these plants in edible form, without adding anything. With this in mind, once we get to the root of things, there’s a clear winner:

Looking at the macros first, potatoes have more carbs while parsnips have more fiber. Potatoes do have more protein too, but given the small numbers involved when it comes to protein we don’t think this is enough of a plus to outweigh the extra fiber in the parsnips.

In the category of vitamins, again a champion emerges: parsnips have more of vitamins B1, B2, B5, B9, C, E, and K, while potatoes have more of vitamins B3, B6, and choline. So, a 7:3 win for parsnips.

When it comes to minerals, parsnips have more calcium copper, manganese, selenium, and zinc, while potatoes have more iron and potassium. Potatoes do also have more sodium, but for most people most of the time, this is not a plus, healthwise. Disregarding the sodium, this category sees a 5:2 win for parsnips.

In short: as with most starchy vegetables, enjoy both in moderation if you feel so inclined, but if you’re picking one, then parsnips are the nutritionally best choice here.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

- Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What pathogen might spark the next pandemic? How scientists are preparing for ‘disease X’

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

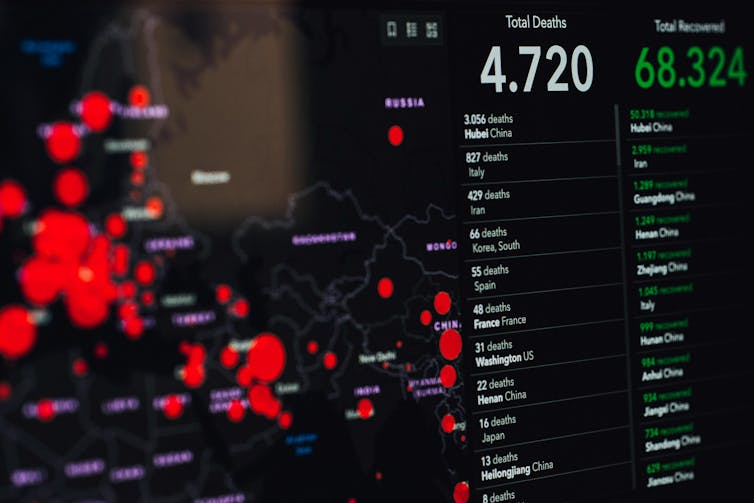

Before the COVID pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) had made a list of priority infectious diseases. These were felt to pose a threat to international public health, but where research was still needed to improve their surveillance and diagnosis. In 2018, “disease X” was included, which signified that a pathogen previously not on our radar could cause a pandemic.

While it’s one thing to acknowledge the limits to our knowledge of the microbial soup we live in, more recent attention has focused on how we might systematically approach future pandemic risks.

Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously talked about “known knowns” (things we know we know), “known unknowns” (things we know we don’t know), and “unknown unknowns” (the things we don’t know we don’t know).

Although this may have been controversial in its original context of weapons of mass destruction, it provides a way to think about how we might approach future pandemic threats.

Anna Shvets/Pexels Influenza: a ‘known known’

Influenza is largely a known entity; we essentially have a minor pandemic every winter with small changes in the virus each year. But more major changes can also occur, resulting in spread through populations with little pre-existing immunity. We saw this most recently in 2009 with the swine flu pandemic.

However, there’s a lot we don’t understand about what drives influenza mutations, how these interact with population-level immunity, and how best to make predictions about transmission, severity and impact each year.

The current H5N1 subtype of avian influenza (“bird flu”) has spread widely around the world. It has led to the deaths of many millions of birds and spread to several mammalian species including cows in the United States and marine mammals in South America.

Human cases have been reported in people who have had close contact with infected animals, but fortunately there’s currently no sustained spread between people.

While detecting influenza in animals is a huge task in a large country such as Australia, there are systems in place to detect and respond to bird flu in wildlife and production animals.

Scientists are continually monitoring a range of pathogens with pandemic potential. Edward Jenner/Pexels It’s inevitable there will be more influenza pandemics in the future. But it isn’t always the one we are worried about.

Attention had been focused on avian influenza since 1997, when an outbreak in birds in Hong Kong caused severe disease in humans. But the subsequent pandemic in 2009 originated in pigs in central Mexico.

Coronaviruses: an ‘unknown known’

Although Rumsfeld didn’t talk about “unknown knowns”, coronaviruses would be appropriate for this category. We knew more about coronaviruses than most people might have thought before the COVID pandemic.

We’d had experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) causing large outbreaks. Both are caused by viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID. While these might have faded from public consciousness before COVID, coronaviruses were listed in the 2015 WHO list of diseases with pandemic potential.

Previous research into the earlier coronaviruses proved vital in allowing COVID vaccines to be developed rapidly. For example, the Oxford group’s initial work on a MERS vaccine was key to the development of AstraZeneca’s COVID vaccine.

Similarly, previous research into the structure of the spike protein – a protein on the surface of coronaviruses that allows it to attach to our cells – was helpful in developing mRNA vaccines for COVID.

It would seem likely there will be further coronavirus pandemics in the future. And even if they don’t occur at the scale of COVID, the impacts can be significant. For example, when MERS spread to South Korea in 2015, it only caused 186 cases over two months, but the cost of controlling it was estimated at US$8 billion (A$11.6 billion).

COVID could be regarded as an ‘unknown known’. Markus Spiske/Pexels The 25 viral families: an approach to ‘known unknowns’

Attention has now turned to the known unknowns. There are about 120 viruses from 25 families that are known to cause human disease. Members of each viral family share common properties and our immune systems respond to them in similar ways.

An example is the flavivirus family, of which the best-known members are yellow fever virus and dengue fever virus. This family also includes several other important viruses, such as Zika virus (which can cause birth defects when pregnant women are infected) and West Nile virus (which causes encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain).

The WHO’s blueprint for epidemics aims to consider threats from different classes of viruses and bacteria. It looks at individual pathogens as examples from each category to expand our understanding systematically.

The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has taken this a step further, preparing vaccines and therapies for a list of prototype pathogens from key virus families. The goal is to be able to adapt this knowledge to new vaccines and treatments if a pandemic were to arise from a closely related virus.

Pathogen X, the ‘unknown unknown’

There are also the unknown unknowns, or “disease X” – an unknown pathogen with the potential to trigger a severe global epidemic. To prepare for this, we need to adopt new forms of surveillance specifically looking at where new pathogens could emerge.

In recent years, there’s been an increasing recognition that we need to take a broader view of health beyond only thinking about human health, but also animals and the environment. This concept is known as “One Health” and considers issues such as climate change, intensive agricultural practices, trade in exotic animals, increased human encroachment into wildlife habitats, changing international travel, and urbanisation.

This has implications not only for where to look for new infectious diseases, but also how we can reduce the risk of “spillover” from animals to humans. This might include targeted testing of animals and people who work closely with animals. Currently, testing is mainly directed towards known viruses, but new technologies can look for as yet unknown viruses in patients with symptoms consistent with new infections.

We live in a vast world of potential microbiological threats. While influenza and coronaviruses have a track record of causing past pandemics, a longer list of new pathogens could still cause outbreaks with significant consequences.

Continued surveillance for new pathogens, improving our understanding of important virus families, and developing policies to reduce the risk of spillover will all be important for reducing the risk of future pandemics.

This article is part of a series on the next pandemic.

Allen Cheng, Professor of Infectious Diseases, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: