I’ve been diagnosed with cancer. How do I tell my children?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

With around one in 50 adults diagnosed with cancer each year, many people are faced with the difficult task of sharing the news of their diagnosis with their loved ones. Parents with cancer may be most worried about telling their children.

It’s best to give children factual and age-appropriate information, so children don’t create their own explanations or blame themselves. Over time, supportive family relationships and open communication help children adjust to their parent’s diagnosis and treatment.

It’s natural to feel you don’t have the skills or knowledge to talk with your children about cancer. But preparing for the conversation can improve your confidence.

Preparing for the conversation

Choose a suitable time and location in a place where your children feel comfortable. Turn off distractions such as screens and phones.

For teenagers, who can find face-to-face conversations confronting, think about talking while you are going for a walk.

Consider if you will tell all children at once or separately. Will you be the only adult present, or will having another adult close to your child be helpful? Another adult might give your children a person they can talk to later, especially to answer questions they might be worried about asking you.

Finally, plan what to do after the conversation, like doing an activity with them that they enjoy. Older children and teenagers might want some time alone to digest the news, but you can suggest things you know they like to do to relax.

Also consider what you might need to support yourself.

Preparing the words

Parents might be worried about the best words or language to use to make sure the explanations are at a level their child understands. Make a plan for what you will say and take notes to stay on track.

The toughest part is likely to be saying to your children that you have cancer. It can help to practise saying those words out aloud.

Ask family and friends for their feedback on what you want to say. Make use of guides by the Cancer Council, which provide age-appropriate wording for explaining medical terms like “cancer”, “chemotherapy” and “tumour”.

Having the conversation

Being open, honest and factual is important. Consider the balance between being too vague, and providing too much information. The amount and type of information you give will be based on their age and previous experiences with illness.

Remember, if things don’t go as planned, you can always try again later.

Start by telling your children the news in a few short sentences, describing what you know about the diagnosis in language suitable for their age. Generally, this information will include the name of the cancer, the area of the body affected and what will be involved in treatment.

Let them know what to expect in the coming weeks and months. Balance hope with reality. For example:

The doctors will do everything they can to help me get well. But, it is going to be a long road and the treatments will make me quite sick.

Check what your child knows about cancer. Young children may not know much about cancer, while primary school-aged children are starting to understand that it is a serious illness. Young children may worry about becoming unwell themselves, or other loved ones becoming sick.

Older children and teenagers may have experiences with cancer through other family members, friends at school or social media.

This process allows you to correct any misconceptions and provides opportunities for them to ask questions. Regardless of their level of knowledge, it is important to reassure them that the cancer is not their fault.

Ask them if there is anything they want to know or say. Talk to them about what will stay the same as well as what may change. For example:

You can still do gymnastics, but sometimes Kate’s mum will have to pick you up if I am having treatment.

If you can’t answer their questions, be OK with saying “I’m not sure”, or “I will try to find out”.

Finally, tell children you love them and offer them comfort.

How might they respond?

Be prepared for a range of different responses. Some might be distressed and cry, others might be angry, and some might not seem upset at all. This might be due to shock, or a sign they need time to process the news. It also might mean they are trying to be brave because they don’t want to upset you.

Children’s reactions will change over time as they come to terms with the news and process the information. They might seem like they are happy and coping well, then be teary and clingy, or angry and irritable.

Older children and teenagers may ask if they can tell their friends and family about what is happening. It may be useful to come together as a family to discuss how to inform friends and family.

What’s next?

Consider the conversation the first of many ongoing discussions. Let children know they can talk to you and ask questions.

Resources might also help; for example, The Cancer Council’s app for children and teenagers and Redkite’s library of free books for families affected by cancer.

If you or other adults involved in the children’s lives are concerned about how they are coping, speak to your GP or treating specialist about options for psychological support.

Cassy Dittman, Senior Lecturer/Head of Course (Undergraduate Psychology), Research Fellow, Manna Institute, CQUniversity Australia; Govind Krishnamoorthy, Senior Lecturer, School of Psychology and Wellbeing, Post Doctoral Fellow, Manna Institute, University of Southern Queensland, and Marg Rogers, Senior Lecturer, Early Childhood Education; Post Doctoral Fellow, Manna Institute, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Behaving During the Holidays

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝It’s hard to “behave” when it comes to holiday indulging…I’m on a low sodium, sugar restricted regimen from my doctor. Trying to get interested in bell peppers as a snack…wish me luck!❞

Good luck! Other low sodium, low sugar snacks include:

- Nuts! Unsalted, of course. We’re biased towards almonds 😉

- Mixed nuts are an especially healthy way to snack, though (assuming you don’t have an allergy, obviously)

- Air-popped popcorn (you can season it, just not with salt/sugar!)

- Fruit (but not fruit juice; it has to be in solid form)

- Peas (not a classic snack food, we know, but they can be enjoyed many ways)

- Seriously, try them frozen or raw! Frozen/raw peas are a great sweet snack.

- Chickpeas are great dried/roasted, by the way, and give much of the same pleasure as a salty snack without being salty! Obviously, this means cooking them without salt, but that’s fine, or if using tinned, choose “in water” rather than “in brine”

- Hummus is also a great healthy snack (check the ingredients for salt if not making it yourself, though) and can be enjoyed as a dip using raw vegetables (celery, carrot sticks, cruciferous vegetables, whatever you prefer)

Enjoy!

Share This Post

- Nuts! Unsalted, of course. We’re biased towards almonds 😉

-

Watermelon vs Cucumber – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing watermelon to cucumber, we picked the cucumber.

Why?

Both are good! But in the battle of the “this is mostly water” salad items, cucumber wins out.

In terms of macros they both are, as we say, mostly water. However, watermelon contains more sugar for the same amount of fiber, contributing to cucumber having the lower glycemic index.

When it comes to vitamins, watermelon does a little better; watermelon has more of vitamins A, B1, B3, B6, C, and E, while cucumber has more of vitamins B2, B5, B9, K, and choline. So, a modest 6:5 win for watermelon.

In the category of minerals, it’s a different story; watermelon has more selenium, while cucumber has more calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc.

Both contain an array of polyphenols; mostly different ones from each other.

As ever, enjoy both. However, adding up the sections, we say cucumber enjoys a marginal win here.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Uses of Delusion – by Dr. Stuart Vyse

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most of us try to live rational lives. We try to make the best decisions we can based on the information we have… And if we’re thoughtful, we even try to be aware of common logical fallacies, and overcome our personal biases too. But is self-delusion ever useful?

Dr. Stuart Vyse, psychologist and Fellow for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, argues that it can be.

From self-fulfilling prophecies of optimism and pessimism, to the role of delusion in love and loss, Dr. Vyse explores what separates useful delusion from dangerous irrationality.

We also read about such questions as (and proposed answers to):

- Why is placebo effect stronger if we attach a ritual to it?

- Why are negative superstitions harder to shake than positive ones?

- Why do we tend to hold to the notion of free will, despite so much evidence for determinism?

The style of the book is conversational, and captivating from the start; a highly compelling read.

Bottom line: if you’ve ever felt yourself wondering if you are deluding yourself and if so, whether that’s useful or counterproductive, this is the book for you!

Click here to check out The Uses of Delusion, and optimize yours!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Stimulant Users Are Caught in Fatal ‘Fourth Wave’ of Opioid Epidemic

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In Pawtucket, Rhode Island, near a storefront advertising “free” cellphones, J.R. sat in an empty back stairwell and showed a reporter how he tries to avoid overdosing when he smokes crack cocaine. KFF Health News is identifying him by his initials because he fears being arrested for using illegal drugs.

It had been several hours since his last hit, and the chatty, middle-aged man’s hands moved quickly. In one hand, he held a glass pipe. In the other, a lentil-size crumb of cocaine.

Or at least J.R. hoped it was cocaine, pure cocaine — uncontaminated by fentanyl, a potent opioid that was linked to about 75% of all overdose deaths in Rhode Island in 2022. He flicked his lighter to “test” his supply. He believed that if it had a “cigar-like sweet smell,” he said, it would mean that the cocaine was laced with fentanyl. He put the pipe to his lips and took a tentative puff. “No sweet,” he said, reassured.

But this method offers only false and dangerous reassurance. A mistake can be fatal.

It is impossible to tell whether a drug contains fentanyl by the taste or smell. “Somebody can believe that they can smell it or taste it, or see it … but that’s not a scientific test,” said Josiah “Jody” Rich, an addiction specialist and researcher who teaches at Brown University. “People are going to die today because they buy some cocaine that they don’t know has fentanyl in it.”

The first wave of the long-running and devastating opioid epidemic began in the United States with the abuse of prescription painkillers in the early 2000s. The second wave involved an increase in heroin use, starting around 2010. The third wave began when powerful synthetic opioids such as fentanyl started appearing in the supply around 2015. Now experts are observing a fourth phase of the deadly epidemic.

The mix of stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines with fentanyl — a synthetic opioid 50 times as powerful as heroin — is driving what experts call the opioid epidemic’s “fourth wave.” The mixture of stimulants and fentanyl presents powerful challenges to efforts to reduce overdoses because many users of stimulants don’t know they are at risk of ingesting opioids, so they don’t take overdose precautions.

The only way to know whether cocaine or other stimulants contain fentanyl is to use drug-checking tools such as fentanyl test strips — a best practice for what’s known as “harm reduction,” now embraced by federal health officials in combating drug overdose deaths. Fentanyl test strips cost as little as $2 for a two-pack online, but many front-line organizations also give them out free.

Nationwide, illicit stimulants mixed with fentanyl were the most common drugs found in fentanyl-related overdoses, according to a study published in 2023 in the scientific journal Addiction. The stimulant in the fatal mixture tends to be cocaine in the Northeast, and methamphetamine in the West and much of the Midwest and South.

“The No. 1 thing that people in the U.S. are dying from in terms of drug overdoses is the combination of fentanyl and a stimulant,’’ said Joseph Friedman, a researcher at UCLA and the study’s lead author. “Black and African Americans are disproportionately affected by this crisis to a large magnitude, especially in the Northeast.”

Friedman was also the lead author of another new study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, that shows the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic is driving up the mortality rate among older Black Americans (ages 55-64) and, more recently, Hispanic people. Friedman said part of the reason street fentanyl is so deadly is that there’s no way to tell how potent it is. Hospitals have safely used medical-grade fentanyl for surgical pain because the potency is strictly regulated, but “the potency fluctuates wildly in the illicit market” Friedman said.

Studies of street drugs, he said, show that in illicit drugs the potency can vary from 1% to 70% fentanyl.

“Imagine ordering a mixed drink in a bar and it contains one to 70 shots,” Friedman said, “and the only way you know is to start drinking it. … There would be a huge number of alcohol overdose deaths.”

Drug-checking technology can provide a rough estimate of fentanyl concentration, he said, but to get a precise measure requires sending drugs to a laboratory.

It’s not clear how much of the latest trend in polydrug use — in which users mix substances, such as cocaine and fentanyl, for example — is accidental versus intentional. It can vary for individual users: a recent study from Millennium Health found that most people who use fentanyl do so at times intentionally and other times unintentionally.

People often use stimulants to power through the rapid withdrawal from fentanyl, Friedman said. And the high-risk practice of using cocaine or meth with heroin, known as “speedballing,” has been around for decades. Other factors include manufacturers’ adding the cheap synthetic opioid to a stimulant to stretch their supply, or dealers mixing up bags.

Researchers say many people still think they are using unadulterated cocaine or crack — a misconception that can be deadly. “Folks who are using stimulants, and not intentionally using opioids, are unprepared to respond to an opioid overdose,” said Brown University epidemiologist Jaclyn White Hughto, “because they don’t perceive themselves to be at risk.” Hughto is a principal investigator in a new, unpublished study called “Preventing Overdoses Involving Stimulants.”

Hughto and the team surveyed more than 260 people in Rhode Island and Massachusetts who use drugs, including some who manufacture and distribute stimulants such as cocaine. More than 60% of the people they interviewed in Rhode Island had bought or used stimulants that they later found out had fentanyl in them. And many of the people interviewed in the study also use drugs alone. That means that if they do overdose, they may not be found until it’s too late.

In 2022, Rhode Island had the fourth-highest rate of overdose deaths involving cocaine in 2022, after Washington, D.C., Delaware, and Vermont, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The fourth wave is also hitting stimulant users who choose pills over what they perceive as more dangerous drugs such as cocaine in an effort to avoid fentanyl. That’s what happened to Jennifer Dubois’ son Cliffton.

Dubois was a single mother raising two Black sons. The older son, Cliffton, had been struggling with addiction since he was 14, she said. Cliffton also had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and a mood disorder.

In March 2020, Cliffton had checked into a rehab program as the pandemic ramped up, Dubois said. Because of the lockdown at rehab, Cliffton was upset about not being able to visit with his mother. “He said, ‘If I can’t see my mom, I can’t do treatment,’” Dubois recalled. “And I begged him” to stay in treatment.

But soon after, Cliffton left the rehab program. He showed up at her door. “And I just cried,” she said.

Dubois’ younger son was living at home. She didn’t want Cliffton doing drugs around his younger brother. So she gave Cliffton an ultimatum: “If you want to stay home, you have to stay drug-free.”

Cliffton went to stay with family friends, first in Atlanta and later in Woonsocket, an old mill city that has Rhode Island’s highest rate of drug overdose deaths.

In August 2020, Cliffton overdosed but was revived. Cliffton later confided that he’d been snorting cocaine in a car with a friend, Dubois said. Hospital records show he tested positive for fentanyl.

“He was really scared,” Dubois said. After the overdose, he tried to “leave the cocaine and the hard drugs alone,” she said. “But he was taking pills.” Eight months later, on April 17, 2021, Cliffton was found unresponsive in the bedroom of a family member’s home.

The night before, Cliffton had bought counterfeit Adderall, according to the police report. What he didn’t know was that the Adderall pill was laced with fentanyl. “He thought by staying away from the street drugs and just taking pills, he was doing better,” Dubois said.

A fentanyl test strip could have saved his life.

This article is from a partnership that includes The Public’s Radio, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Who will look after us in our final years? A pay rise alone won’t solve aged-care workforce shortages

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Aged-care workers will receive a significant pay increase after the Fair Work Commission ruled they deserved substantial wage rises of up to 28%. The federal government has committed to the increases, but is yet to announce when they will start.

But while wage rises for aged-care workers are welcome, this measure alone will not fix all workforce problems in the sector. The number of people over 80 is expected to triple over the next 40 years, driving an increase in the number of aged care workers needed.

How did we get here?

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, which delivered its final report in March 2021, identified a litany of tragic failures in the regulation and delivery of aged care.

The former Liberal government was dragged reluctantly to accept that a total revamp of the aged-care system was needed. But its weak response left the heavy lifting to the incoming Labor government.

The current government’s response started well, with a significant injection of funding and a promising regulatory response. But it too has failed to pursue a visionary response to the problems identified by the Royal Commission.

Action was needed on four fronts:

- ensuring enough staff to provide care

- building a functioning regulatory system to encourage good care and weed out bad providers

- designing and introducing a fair payment system to distribute funds to providers and

- implementing a financing system to pay for it all and achieve intergenerational equity.

A government taskforce which proposed a timid response to the fourth challenge – an equitable financing system – was released at the start of last week.

Consultation closed on a very poorly designed new regulatory regime the week before.

But the big news came at end of the week when the Fair Work Commission handed down a further determination on what aged-care workers should be paid, confirming and going beyond a previous interim determination.

What did the Fair Work Commission find?

Essentially, the commission determined that work in industries with a high proportion of women workers has been traditionally undervalued in wage-setting. This had consequences for both care workers in the aged-care industry (nurses and Certificate III-qualified personal-care workers) and indirect care workers (cleaners, food services assistants).

Aged-care staff will now get significant pay increases – 18–28% increase for personal care workers employed under the Aged Care Award, inclusive of the increase awarded in the interim decision.

The commission determined aged care work was undervalued.

Shutterstock/Toa55Indirect care workers were awarded a general increase of 3%. Laundry hands, cleaners and food services assistants will receive a further 3.96% on the grounds they “interact with residents significantly more regularly than other indirect care employees”.

The final increases for registered and enrolled nurses will be determined in the next few months.

How has the sector responded?

There has been no push-back from employer groups or conservative politicians. This suggests the uplift is accepted as fair by all concerned.

The interim increases of up to 15% probably facilitated this acceptance, with the recognition of the community that care workers should be paid more than fast food workers.

There was no criticism from aged-care providers either. This is probably because they are facing difficulty in recruiting staff at current wage rates. And because government payments to providers reflect the actual cost of aged care, increased payments will automatically flow to providers.

When the increases will flow has yet to be determined. The government is due to give its recommendations for staging implementation by mid-April.

Is the workforce problem fixed?

An increase in wages is necessary, but alone is not sufficient to solve workforce shortages.

The health- and social-care workforce is predicted to grow faster than any other sector over the next decade. The “care economy” will grow from around 8% to around 15% of GDP over the next 40 years.

This means a greater proportion of school-leavers will need to be attracted to the aged-care sector. Aged care will also need to attract and retrain workers displaced from industries in decline and attract suitably skilled migrants and refugees with appropriate language skills.

Aged care will need to attract workers from other sectors.

nastya_ph/ShutterstockThe caps on university and college enrolments imposed by the previous government, coupled with weak student demand for places in key professions (such as nursing), has meant workforce shortages will continue for a few more years, despite the allure of increased wages.

A significant increase in intakes into university and vocational education college courses preparing students for health and social care is still required. Better pay will help to increase student demand, but funding to expand place numbers will ensure there are enough qualified staff for the aged-care system of the future.

Stephen Duckett, Honorary Enterprise Professor, School of Population and Global Health, and Department of General Practice and Primary Care, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

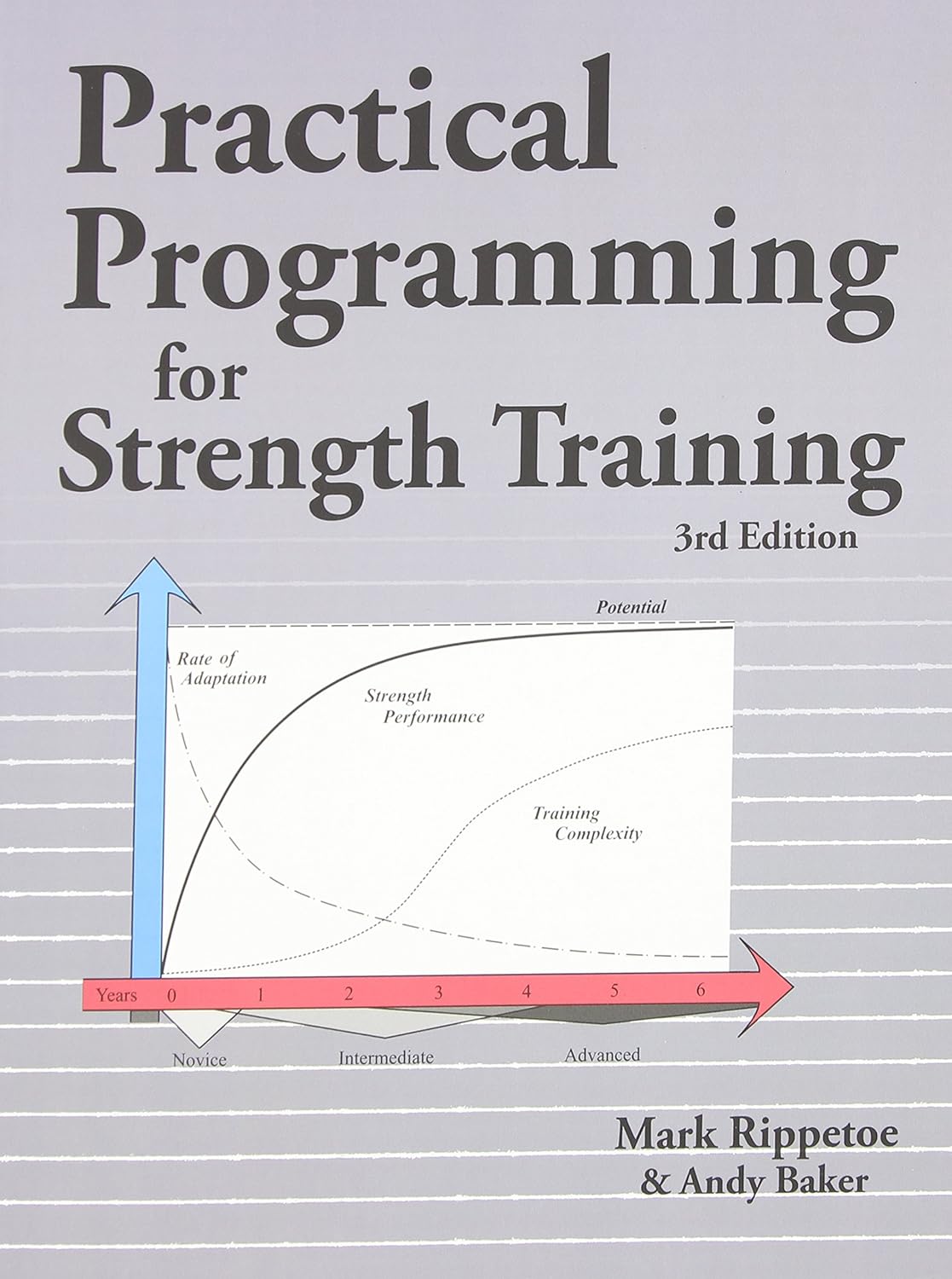

Practical Programming for Strength Training – by Mark Rippetoe & Andy Baker

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Strength training is an important part of overall health maintenance, but it can be hard to find a good guide to progressive strength improvement that isn’t a bodybuilding book.

This one gives a ground-upwards approach, explaining small details to even quite basic things, before taking the reader through to more advanced progressions, and how to get the most strength-building out of each exercise over time.

As such, this is a good book for anyone of any level from beginner to quite experienced, and you can hop in at any point since there are always catch-up summaries and/or reiterations of the previous concepts that we’re now building on from.

The authors do also talk nutrition, hormones, and so forth, but most of it is about the exercises and the progressions thereof.

There is a slightly patronizing chapter towards the end, about “special populations”, for example offering “novice and intermediate training for women”, but it doesn’t take away from the majority of the book, as the exercises don’t care about your gender. Muscles are muscles, and we all start from wherever we are. Yes, testosterone boosts muscle mass, but let’s face it, there are a lot of women in the world who are stronger than a lot of men.

One thing to bear in mind is that a lot of this is barbell training, so you will need a barbell (or access to one at a gym). If purely bodyweight training is your preference, or perhaps some other form of weightlifting (e.g. kettlebells or such) then this isn’t the book for that.

Bottom line: if strength training is your focus and you like barbells, then this is a great book to take you quite a way along that road.

Click here to check out Practical Programming For Strength Training, and get stronger!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: