Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs

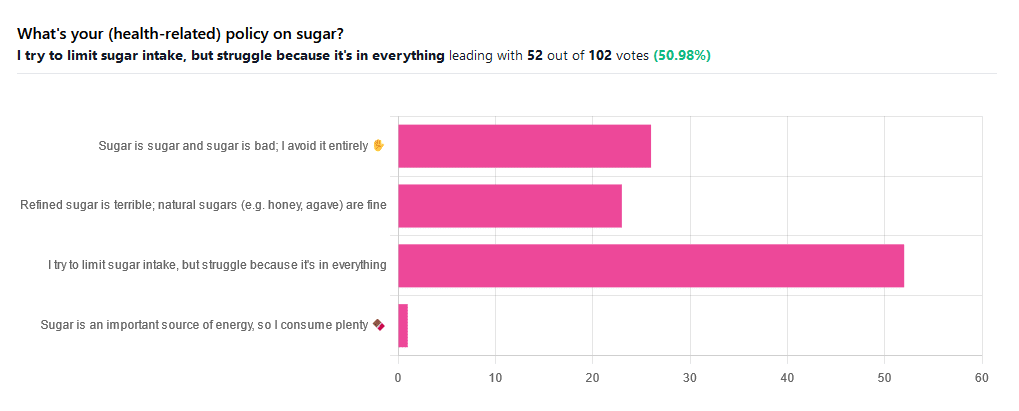

We asked you for your (health-related) policy on sugar. The trends were as follows:

- About half of all respondents voted for “I try to limit sugar intake, but struggle because it’s in everything”

- About a quarter of all respondents voted for “Refined sugar is terrible; natural sugars (e.g. honey, agave) are fine”

- About a quarter of all respondents voted for “Sugar is sugar and sugar is bad; I avoid it entirely”

- One (1) respondent voted for “Sugar is an important source of energy, so I consume plenty”

Writer’s note: I always forget to vote in these, but I’d have voted for “I try to limit sugar intake, but struggle because it’s in everything”.

Sometimes I would like to make my own [whatever] to not have the sugar, but it takes so much more time, and often money too.

So while I make most things from scratch (and typically spend about an hour cooking each day), sometimes store-bought is the regretfully practical timesaver/moneysaver (especially when it comes to condiments).

So, where does the science stand?

There has, of course, been a lot of research into the health impact of sugar.

Unfortunately, a lot of it has been funded by sugar companies, which has not helped. Conversely, there are also studies funded by other institutions with other agendas to push, and some of them will seek to make sugar out to be worse than it is.

So for today’s mythbusting overview, we’ve done our best to quality-control studies for not having financial conflicts of interest. And of course, the usual considerations of favoring high quality studies where possible Large sample sizes, good method, human subjects, that sort of thing.

Sugar is sugar and sugar is bad: True or False?

False and True, respectively.

- Sucrose is sucrose, and is generally bad.

- Fructose is fructose, and is worse.

Both ultimately get converted into glycogen (if not used immediately for energy), but for fructose, this happens mostly* in the liver, which a) taxes it b) goes very unregulated by the pancreas, causing potentially dangerous blood sugar spikes.

This has several interesting effects:

- Because fructose doesn’t directly affect insulin levels, it doesn’t cause insulin insensitivity (yay)

- Because fructose doesn’t directly affect insulin levels, this leaves hyperglycemia untreated (oh dear)

- Because fructose is metabolized by the liver and converted to glycogen which is stored there, it’s one of the main contributors to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (at this point, we’re retracting our “yay”)

Read more: Fructose and sugar: a major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

*”Mostly” in the liver being about 80% in the liver. The remaining 20%ish is processed by the kidneys, where it contributes to kidney stones instead. So, still not fabulous.

Fructose is very bad, so we shouldn’t eat too much fruit: True or False?

False! Fruit is really not the bad guy here. Fruit is good for you!

Fruit does contain fructose yes, but not actually that much in the grand scheme of things, and moreover, fruit contains (unless you have done something unnatural to it) plenty of fiber, which mitigates the impact of the fructose.

- A medium-sized apple (one of the most sugary fruits there is) might contain around 11g of fructose

- A tablespoon of high-fructose corn syrup can have about 27g of fructose (plus about 3g glucose)

Read more about it: Effects of high-fructose (90%) corn syrup on plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and normal subjects

However! The fiber content (in fruit) mitigates the impact of the fructose almost entirely anyway.

And if you take fruits that are high in sugar and/but high in polyphenols, like berries, they now have a considerable net positive impact on glycemic health:

- Polyphenols and Glycemic Control

- Polyphenols and their effects on diabetes management: A review

- Dietary polyphenols as antidiabetic agents: Advances and opportunities

You may be wondering: what was that about “unless you have done something unnatural to it”?

That’s mostly about juicing. Juicing removes much (or all) of the fiber, and if you do that, you’re basically back to shooting fructose into your veins:

- Effect of Fruit Juice on Glucose Control and Insulin Sensitivity in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of 12 Randomized Controlled Trials

- Intake of Fruit, Vegetables, and Fruit Juices and Risk of Diabetes in Women

Natural sugars like honey, agave, and maple syrup, are healthier than refined sugars: True or False?

True… Sometimes, and sometimes marginally.

This is partly because of the glycemic index and glycemic load. The glycemic index scores tail off thus:

- table sugar = 65

- maple syrup = 54

- honey = 46

- agave syrup = 15

So, that’s a big difference there between agave syrup and maple syrup, for example… But it might not matter if you’re using a very small amount, which means it may have a high glycemic index but a low glycemic load.

Note, incidentally, that table sugar, sucrose, is a disaccharide, and is 50% glucose and 50% fructose.

The other more marginal health benefits come from that fact that natural sugars are usually found in foods high in other nutrients. Maple syrup is very high in manganese, for example, and also a fair source of other minerals.

But… Because of its GI, you really don’t want to be relying on it for your nutrients.

Wait, why is sugar bad again?

We’ve been covering mostly the more “mythbusting” aspects of different forms of sugar, rather than the less controversial harms it does, but let’s give at least a cursory nod to the health risks of sugar overall:

- Obesity and associated metabolic risk

- Main contributor to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Increased risk of heart disease

- Insulin resistance and diabetes risk

- Cellular aging (shortened telomeres)

- 95% increased cancer risk

That last one, by the way, was a huge systematic review of 37 large longitudinal cohort studies. Results varied depending on what, specifically, was being examined (e.g. total sugar, fructose content, sugary beverages, etc), and gave up to 200% increased cancer risk in some studies on sugary beverages, but 95% increased risk is a respectable example figure to cite here, pertaining to added sugars in foods.

And finally…

The 56 Most Common Names for Sugar (Some Are Tricky)

How many did you know?

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can You Be Fat AND Fit?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The short answer is “yes“.

And as for what that means for your heart and/or all-cause mortality risk: it’s just as good as being fit at a smaller size, and furthermore, it’s better than being less fit at a smaller size.

Here’s the longer answer:

The science

A research team did a systematic review looking at multiple large cohort studies examining the associations between:

- Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular disease risk

- Cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality

- BMI and cardiovascular disease risk

- BMI and all-cause mortality

However, they also took this further, and tabulated the data such that they could also establish the cardiovascular disease mortality risk and all-cause mortality risk of:

- Unfit people with “normal” BMI

- Unfit people with “overweight” BMI

- Unfit people with “obese” BMI

- Fit people with “normal” BMI

- Fit people with “overweight” BMI

- Fit people with “obese” BMI

Before we move on, let’s note for the record that BMI is a woeful system in any case, for enough reasons to fill a whole article:

Now, with that in mind, let’s get to the results:

What they found

For cardiovascular disease mortality risk of unfit people specifically, compared to fit people of “normal” BMI:

- Unfit people with “normal” BMI: 2.04x higher risk.

- Unfit people with “overweight” BMI: 2.58x higher risk.

- Unfit people with “obese” BMI: 3.35x higher risk

So here we can see that if you are unfit, then being heavier will indeed increase your CVD mortality risk.

For all-cause mortality risk of unfit people specifically, compared to fit people of “normal” BMI:

- Unfit people with “normal” BMI: 1.92x higher risk.

- Unfit people with “overweight” BMI: 1.82x higher risk.

- Unfit people with “obese” BMI: 2.04x higher risk

This time we see that if you are unfit, then being heavier or lighter than “overweight” will increase your all-cause mortality risk.

So, what about if you are fit? Then being heavier or lighter made no significant difference to either CVD mortality risk or all-cause mortality risk.

Fit individuals, regardless of weight category (normal, overweight, or obese), had significantly lower mortality risks compared to unfit individuals in any weight category.

Note: not just “compared to unfit individuals in their weight category”, but compared to unfit individuals in any weight category.

In other words, if you are obese and have good cardiorespiratory fitness, you will (on average) live longer than an unfit person with “normal” BMI.

You can find the paper itself here, if you want to examine the data and/or method:

Cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Ok, so how do I improve the kind of fitness that they measured?

They based their cardiorespiratory fitness on VO2 Max, which scientific consensus holds to be a good measure of how efficiently your body can use oxygen—thus depending on your heart and lungs being healthy.

If you use a fitness tracker that tracks your exercise and your heart rate, it will estimate your VO2 Max for you—to truly measure the VO2 Max itself directly, you’ll need a lot more equipment; basically, access to a lab that tests this. But the estimates are fairly accurate, and so good enough for most personal purposes that aren’t hard-science research.

Next, you’ll want to do this:

53 Studies Later: The Best Way to Improve VO2 Max

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Yes, you do need to clean your tongue. Here’s how and why

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Has your doctor asked you to stick out your tongue and say “aaah”? While the GP assesses your throat, they’re also checking out your tongue, which can reveal a lot about your health.

The doctor will look for any changes in the tongue’s surface or how it moves. This can indicate issues in the mouth itself, as well as the state of your overall health and immunity.

But there’s no need to wait for a trip to the doctor. Cleaning your tongue twice a day can help you check how your tongue looks and feels – and improve your breath.

luisrsphoto/Shutterstock What does a healthy tongue look like?

Our tongue plays a crucial role in eating, talking and other vital functions. It is not a single muscle but rather a muscular organ, made up of eight muscle pairs that help it move.

The surface of the tongue is covered by tiny bumps that can be seen and felt, called papillae, giving it a rough surface.

These are sometimes mistaken for taste buds – they’re not. Of your 200,000-300,000 papillae, only a small fraction contain taste buds. Adults have up to 10,000 taste buds and they are invisible to the naked eye, concentrated mainly on the tip, sides and back of the tongue. https://www.youtube.com/embed/uYvpUl7li9Y?wmode=transparent&start=0

A healthy tongue is pink although the shade may vary from person to person, ranging from dark to light pink.

A small amount of white coating can be normal. But significant changes or discolouration may indicate a disease or other issues.

How should I clean my tongue?

Cleaning your tongue only takes around 10-15 seconds, but it’s is a good way to check in with your health and can easily be incorporated into your teeth brushing routine.

Build-up can occur if you stop brushing or scraping your tongue even for a few days. Anthony Shkraba/Pexels You can clean your tongue by gently scrubbing it with a regular toothbrush. This dislodges any food debris and helps prevent microbes building up on its rough textured surface.

Or you can use a special tongue scraper. These curved instruments are made of metal or plastic, and can be used alone or accompanied by scrubbing with your toothbrush.

Your co-workers will thank you as well – cleaning your tongue can help combat stinky breath. Tongue scrapers are particularly effective at removing the bacteria that commonly causes bad breath, hidden in the tongue’s surface.

What’s that stuff on my tongue?

So, you’re checking your tongue during your twice-daily clean, and you notice something different. Noting these signs is the first step. If you observe any changes and they worry you, you should talk to your GP.

Here’s what your tongue might be telling you.

White coating

Developing a white coating on the tongue’s surface is one of the most common changes in healthy people. This can happen if you stop brushing or scraping the tongue, even for a few days.

In this case, food debris and microbes have accumulated and caused plaque. Gentle scrubbing or scraping will remove this coating. Removing microbes reduces the risk of chronic infections, which can be transferred to other organs and cause serious illnesses.

Scrubbing or scraping your tongue only takes around ten seconds and can be done while brushing your teeth. Ketut Subiyanto/Pexels Yellow coating

This may indicate oral thrush, a fungal infection that leaves a raw surface when scrubbed.

Oral thrush is common in elderly people who take multiple medications or have diabetes. It can also affect children and young adults after an illness, due to the temporary suppression of the immune system or antibiotic use.

If you have oral thrush, a doctor will usually prescribe a course of anti-fungal medication for at least a month.

Black coating

Smoking or consuming a lot of strong-coloured food and drink – such as tea and coffee, or dishes with tumeric – can cause a furry appearance. This is known as a black hairy tongue. It’s not hair, but an overgrowth of bacteria which may indicate poor oral hygiene.

Smoking can add to poor oral hygiene and make the tongue look black. Sophon Nawit/Shutterstock Pink patches

Pink patches surrounded by a white border can make your tongue look like a map – this is called “geographic tongue”. It’s not known what causes this condition, which usually doesn’t require treatment.

Pain and inflammation

A red, sore tongue can indicate a range of issues, including:

- nutritional deficiencies such as folic acid or vitamin B12

- diseases including pernicious anaemia, Kawasaki disease and scarlet fever

- inflammation known as glossitis

- injury from hot beverages or food

- ulcers, including cold sores and canker sores

- burning mouth syndrome.

Dryness

Many medications can cause dry mouth, also called xerostomia. These include antidepressants, anti-psychotics, muscle relaxants, pain killers, antihistamines and diuretics. If your mouth is very dry, it may hurt.

What about cancer?

White or red patches on the tongue that can’t be scraped off, are long-standing or growing need to checked out by a dental professional as soon as possible, as do painless ulcers. These are at a higher risk of turning into cancer, compared to other parts of the mouth.

Oral cancers have low survival rates due to delayed detection – and they are on the rise. So checking your tongue for changes in colour, texture, sore spots or ulcers is critical.

Dileep Sharma, Professor and Head of Discipline – Oral Health, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Brain Benefits in 3 Months…through walking?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Keeping it Simple

Today’s video (below) is another Big Think production (can you tell that we love their work?). Wendy Suzuki does a wonderful job of breaking down the brain benefits of exercise into three categories, within three minutes.

The first question to ask yourself is: what is your current level of fitness?

Low Fitness

Exercising, even if it’s just going on a walk, 2-3 times a week improves baseline mood state, as well as enhances prefrontal and hippocampal function. These areas of the brain are crucial for complex behaviors like planning and personality development, as well as memory and learning.

Mid Fitness

The suggested regimen is, without surprise, to slightly increase your regular workouts over three months. Whilst you’re already getting the benefits from the low-fitness routine, there is a likelihood that you’ll increase your baseline dopamine and serotonin levels–which, of course, we love! Read more on dopamine here, here, or here.

High Fitness

If you consider yourself in the high fitness bracket then well done, you’re doing an amazing job! Wendy Suzuki doesn’t make many suggestions for you; all she mentions is that there is the possibility of “too much” exercise actually having negative effects on the brain. However, if you’re not competing at an Olympic level, you should be fine.

Fitness and Exercise in General

Of course, fitness and exercise are both very broad terms. We would suggest that you find an exercise routine that you genuinely enjoy–something that is easy to continue over the long term. Try browsing different areas of exercise to see what resonates with you. For instance, Total Fitness After 40 is a great book on all things fitness in the second half of your life. Alternatively, search through our archive for fitness-related material.

Anyway, without further ado, here is today’s video:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Great Cholesterol Myth, Revised and Expanded – by Dr. Jonny Bowden and Dr. Stephen Sinatra

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The topic of cholesterol, and saturated fat for that matter, is a complex and often controversial one. How does this book treat it?

With strong opinions, is how—but backed by good science. The authors, a nutritionist and a cardiologist, pull no punches about outdated and/or cherry-picked science, and instead make the case for looking at what, statistically speaking, appear to be the real strongest risk factors.

So, are they advocating for Dave Asprey-style butter-guzzling, or “the carnivore diet”? No, no they are not. Those things remain unhealthy, even if they give some short-term gains (of energy levels, weight loss, etc).

They do advocate, however, for enjoying saturated fats in moderation, and instead of certain polyunsaturated seed oils that do far worse. They also advocate strongly for avoiding sugar, stress, and (for different reasons) statins (in most people’s cases).

They also demystify in clear terms, and often with diagrams and infographics, the various kinds of fats and their components, broken down in far more detail than any other pop-science source this reviewer has seen.

Bottom line: if you want to take a scientific approach to heart health, this book can help you to focus on what will actually make the biggest difference.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Brain Alarm Signs That Warn Of Dementia

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When it comes to predicting age-related cognitive impairment:

First there are genetic factors to take into account (such as the APOE4 gene for Alzheimer’s), as well as things such as age and sex.

When it comes to sex, by the way, what matters here is hormones, which is why [it seems; this as technically as yet unproven with full rigor, but the hypothesis is sound and there is a body of evidence gradually being accumulated to support it] postmenopausal women with untreated menopause get Alzheimer’s at a higher rate and deteriorate more quickly:

Alzheimer’s Sex Differences May Not Be What They Appear

Next, there are obviously modifiable lifestyle factors to take into account, things that will reduce your risk such as getting good sleep, good diet, good exercise, and abstaining from alcohol and smoking, as well as oft-forgotten things such as keeping cognitively active and, equally importantly, socially active:

How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

(the article outlines what matters the most in each of the above areas, by the way, so that you can get the most bang-for-buck in terms of lifestyle adjustments)

Lastly (in the category of risk factors), there are things to watch out for in the blood such as hypertension and high cholesterol.

Nipping it in the blood

In new research (so new it is still ongoing, but being at year 2 of a 4-year prospective study, they have published a paper with their results so far), researchers have:

- started with the premise “dementia is preceded by mild cognitive impairment”

- then, asked the question “what are the biometric signs of mild cognitive impairment?”

Using such tools as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) while the participants performed cognitive tasks, they were able to record changes in plasma levels of extracellular vesicles, assessing them with small-particle flow cytometry.

Translating from sciencese: they gave the participants mental tasks, and while they completed them, the researchers scanned their brains and monitored blood flow and the brain’s ability to compensate for any lack of it.

What they found:

- in young adults, blood flow increased, facilitating neurovascular coupling (this is good)

- in older adults, blood flow did not increase as much, but they engaged other areas of the brain to compensate, by what’s called functional connectivity (this is next best)

- in those with mild cognitive impairment, blood flow was reduced, and they did not have the ability to compensate by functional connectivity (this is not good)

They also performed a liquid biopsy, which sounds alarming but it just means they took some blood, and tested this for density of cerebrovascular endothelial extracellular vesicles (CEEVs), which—in more prosaic words—are bits from the cells lining the blood vessels in the brain.

People with mild cognitive impairment had more of these brain bits in their blood than those without.

You can read the paper itself here:

What this means

The science here is obviously still young (being as it is still in progress), but this will likely contribute greatly to early warning signs of dementia, by catching mild cognitive impairment in its early stages, by means of a simple blood test, instead of years of wondering before getting a dementia diagnosis.

And of course, forewarned is forearmed, so if this is something that could be done as a matter of routine upon hitting the age of, say, 65 and then periodically thereafter, it would catch a lot of cases while there’s still more time to turn things around.

As for how to turn things around, well, we imagine you have now read our “How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk” article linked up top (if not, we recommend checking it out), and there is also…

Do Try This At Home: The 12-Week Brain Fitness Program To Measurably Boost Your Brain

Take care!

When it comes to predicting age-related cognitive impairment:

First there are genetic factors to take into account (such as the APOE4 gene for Alzheimer’s), as well as things such as age and sex.

When it comes to sex, by the way, what matters here is hormones, which is why [it seems; this as technically as yet unproven with full rigor, but the hypothesis is sound and there is a body of evidence gradually being accumulated to support it] postmenopausal women with untreated menopause get Alzheimer’s at a higher rate and deteriorate more quickly:

Alzheimer’s Sex Differences May Not Be What They Appear

Next, there are obviously modifiable lifestyle factors to take into account, things that will reduce your risk such as getting good sleep, good diet, good exercise, and abstaining from alcohol and smoking, as well as oft-forgotten things such as keeping cognitively active and, equally importantly, socially active:

How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

(the article outlines what matters the most in each of the above areas, by the way, so that you can get the most bang-for-buck in terms of lifestyle adjustments)

Lastly (in the category of risk factors), there are things to watch out for in the blood such as hypertension and high cholesterol.

Nipping it in the blood

In new research (so new it is still ongoing, but being at year 2 of a 4-year prospective study, they have published a paper with their results so far), researchers have:

- started with the premise “dementia is preceded by mild cognitive impairment”

- then, asked the question “what are the biometric signs of mild cognitive impairment?”

Using such tools as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) while the participants performed cognitive tasks, they were able to record changes in plasma levels of extracellular vesicles, assessing them with small-particle flow cytometry.

Translating from sciencese: they gave the participants mental tasks, and while they completed them, the researchers scanned their brains and monitored blood flow and the brain’s ability to compensate for any lack of it.

What they found:

- in young adults, blood flow increased, facilitating neurovascular coupling (this is good)

- in older adults, blood flow did not increase as much, but they engaged other areas of the brain to compensate, by what’s called functional connectivity (this is next best)

- in those with mild cognitive impairment, blood flow was reduced, and they did not have the ability to compensate by functional connectivity (this is not good)

They also performed a liquid biopsy, which sounds alarming but it just means they took some blood, and tested this for density of cerebrovascular endothelial extracellular vesicles (CEEVs), which—in more prosaic words—are bits from the cells lining the blood vessels in the brain.

People with mild cognitive impairment had more of these brain bits in their blood than those without.

You can read the paper itself here:

What this means

The science here is obviously still young (being as it is still in progress), but this will likely contribute greatly to early warning signs of dementia, by catching mild cognitive impairment in its early stages, by means of a simple blood test, instead of years of wondering before getting a dementia diagnosis.

And of course, forewarned is forearmed, so if this is something that could be done as a matter of routine upon hitting the age of, say, 65 and then periodically thereafter, it would catch a lot of cases while there’s still more time to turn things around.

As for how to turn things around, well, we imagine you have now read our “How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk” article linked up top (if not, we recommend checking it out), and there is also…

Do Try This At Home: The 12-Week Brain Fitness Program To Measurably Boost Your Brain

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem. What should we call mental distress?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We talk about mental health more than ever, but the language we should use remains a vexed issue.

Should we call people who seek help patients, clients or consumers? Should we use “person-first” expressions such as person with autism or “identity-first” expressions like autistic person? Should we apply or avoid diagnostic labels?

These questions often stir up strong feelings. Some people feel that patient implies being passive and subordinate. Others think consumer is too transactional, as if seeking help is like buying a new refrigerator.

Advocates of person-first language argue people shouldn’t be defined by their conditions. Proponents of identity-first language counter that these conditions can be sources of meaning and belonging.

Avid users of diagnostic terms see them as useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can box people in and misrepresent their problems as pathologies.

Underlying many of these disagreements are concerns about stigma and the medicalisation of suffering. Ideally the language we use should not cast people who experience distress as defective or shameful, or frame everyday problems of living in psychiatric terms.

Our new research, published in the journal PLOS Mental Health, examines how the language of distress has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here’s what we found.

Engin Akyurt/Pexels Generic terms for the class of conditions

Generic terms – such as mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem – have largely escaped attention in debates about the language of mental ill health. These terms refer to mental health conditions as a class.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include mental, mental health, psychiatric and psychological, and common nouns include condition, disease, disorder, disturbance, illness, and problem. Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ in their connotations. Disease and illness sound the most medical, whereas condition, disturbance and problem need not relate to health. Mental implies a direct contrast with physical, whereas psychiatric implicates a medical specialty.

Mental health problem, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathologising. It implies that something is to be solved rather than treated, makes no direct reference to medicine, and carries the positive connotations of health rather than the negative connotation of illness or disease.

Is ‘mental health problem’ actually less pathologising? Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock Arguably, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls the “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency for language to evolve new terms to escape (at least temporarily) the offensive connotations of those they replace.

English linguist Hazel Price argues that mental health has increasingly come to replace mental illness to avoid the stigma associated with that term.

How has usage changed over time?

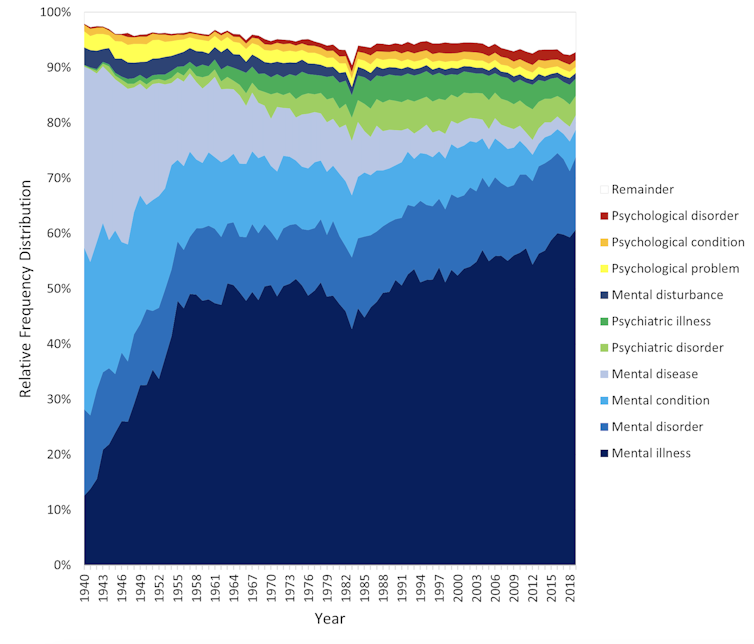

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the popularity of 24 generic terms: every combination of the nouns and adjectives listed above.

We explore the frequency with which each term appears from 1940 to 2019 in two massive text data sets representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The findings are very similar in both data sets.

The figure presents the relative popularity of the top ten terms in the larger data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined into the remainder.

Relative popularity of alternative generic terms in the Google Books corpus. Haslam et al., 2024, PLOS Mental Health. Several trends appear. Mental has consistently been the most popular adjective component of the generic terms. Mental health has become more popular in recent years but is still rarely used.

Among nouns, disease has become less widely used while illness has become dominant. Although disorder is the official term in psychiatric classifications, it has not been broadly adopted in public discourse.

Since 1940, mental illness has clearly become the preferred generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, it has steadily risen in popularity.

Does it matter?

Our study documents striking shifts in the popularity of generic terms, but do these changes matter? The answer may be: not much.

One study found people think mental disorder, mental illness and mental health problem refer to essentially identical phenomena.

Other studies indicate that labelling a person as having a mental disease, mental disorder, mental health problem, mental illness or psychological disorder makes no difference to people’s attitudes toward them.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, but the evidence to date suggests they are minimal.

The labels we use may not have a big impact on levels of stigma. Pixabay/Pexels Is ‘distress’ any better?

Recently, some writers have promoted distress as an alternative to traditional generic terms. It lacks medical connotations and emphasises the person’s subjective experience rather than whether they fit an official diagnosis.

Distress appears 65 times in the 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing Act, usually in the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By implication, distress is a broad concept akin to but not synonymous with mental ill health.

But is distress destigmatising, as it was intended to be? Apparently not. According to one study, it was more stigmatising than its alternatives. The term may turn us away from other people’s suffering by amplifying it.

So what should we call it?

Mental illness is easily the most popular generic term and its popularity has been rising. Research indicates different terms have little or no effect on stigma and some terms intended to destigmatise may backfire.

We suggest that mental illness should be embraced and the proliferation of alternative terms such as mental health problem, which breed confusion, should end.

Critics might argue mental illness imposes a medical frame. Philosopher Zsuzsanna Chappell disagrees. Illness, she argues, refers to subjective first-person experience, not to an objective, third-person pathology, like disease.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centres the individual and their connections. “When I identify my suffering as illness-like,” Chappell writes, “I wish to lay claim to a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As generic terms go, mental illness is a healthy option.

Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne and Naomi Baes, Researcher – Social Psychology/ Natural Language Processing, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: