Psychology Sunday Rewind: Healing Family Rifts

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Estrangement, And How To Heal It

The following article was first published a little under six months ago, and it proved to be our most popular “Psychology Sunday” article of the year.

We republish it today, in case it might also be of value to readers who have joined us since

Having written before about how deleterious to the health loneliness and isolation can be, and what things can be done about it, we had a request to write about…

❝Reconciliation of relationships in particular estrangement mother adult daughter❞

And, this is not only an interesting topic, but a very specific one that affects more people than is commonly realized!

In fact, a recent 800-person study found that more than 43% of people experienced family estrangement of one sort or another, and a more specific study of more than 2,000 mother-child pairs found that more than 11% of mothers were estranged from at least one adult child.

So, if you think of the ten or so houses nearest to you, probably at least one of them contains a parent estranged from at least one adult child. Maybe it’s yours. Either way, we hope this article will give you some pause for thought.

Which way around?

It makes a difference to the usefulness of this article whether any given reader experiencing estrangement is the parent or the adult child. We’re going to assume the reader is the parent. It also makes a difference who did the estranging. That’s usually the adult child.

So, we’re broadly going to write with that expectation.

Why does it happen?

When our kids are small, we as parents hold all the cards. It may not always feel that way, but we do. We control our kids’ environment, we influence their learning, we buy the food they eat and the clothes they wear. If they want to go somewhere, we probably have to take them. We can even set and enforce rules on a whim.

As they grow, so too does their independence, and it can be difficult for us as parents to relinquish control, but we’re going to have to at some point. Assuming we are good parents, we just hope we’ve prepared them well enough for the world.

Once they’ve flown the nest and are living their own adult lives, there’s an element of inversion. They used to be dependent on us; now, not only do they not need us (this is a feature not a bug! If we have been good parents, they will be strong without us, and in all likelihood one day, they’re going to have to be), but also…

We’re more likely to need them, now. Not just in the “oh if we have kids they can look after us when we’re old” sense, but in that their social lives are growing as ours are often shrinking, their family growing, while ours, well, it’s the same family but they’re the gatekeepers to that now.

If we have a good relationship, this goes fine. However, it might only take one big argument, one big transgression, or one “final straw”, when the adult child decides the parent is more trouble than they’re worth.

And, obviously, that’s going to hurt. But it’s pretty much how it pans out, according to studies:

Here be science: Tensions in the Parent and Adult Child Relationship: Links to Solidarity and Ambivalence

How to fix it, step one

First, figure out what went wrong.

Resist any urge to protect your own feelings with a defensive knee-jerk “I don’t know; I was a good, loving parent”. That’s a very natural and reasonable urge and you’re quite possibly correct, but it won’t help you here.

Something pushed them away. And, it will almost certainly have been a push factor from you, not a pull factor from whoever is in their life now. It’s easy to put the blame externally, but that won’t fix anything.

And, be honest with yourself; this isn’t a job interview where we have to present a strength dressed up as a “greatest weakness” for show.

You can start there, though! If you think “I was too loving”, then ok, how did you show that love? Could it have felt stifling to them? Controlling? Were you critical of their decisions?

It doesn’t matter who was right or wrong, or even whether or not their response was reasonable. It matters that you know what pushed them away.

How to fix it, step two

Take responsibility, and apologize. We’re going to assume that your estrangement is such that you can, at least, still get a letter to them, for example. Resist the urge to argue your case.

Here’s a very good format for an apology; please consider using this template:

The 10-step (!) apology that’s so good, you’ll want to make a note of it

You may have to do some soul-searching to find how you will avoid making the same mistake in the future, that you did in the past.

If you feel it’s something you “can’t change”, then you must decide what is more important to you. Only you can make that choice, but you cannot expect them to meet you halfway. They already made their choice. In the category of negotiation, they hold all the cards now.

How to fix it, step three

Now, just wait.

Maybe they will reply, forgiving you. If they do, celebrate!

Just be aware that once you reconnect is not the time to now get around to arguing your case from before. It will never be the time to get around to arguing your case from before. Let it go.

Nor should you try to exact any sort of apology from them for estranging you, or they will at best feel resentful, wonder if they made a mistake in reconnecting, and withdraw.

Instead, just enjoy what you have. Many people don’t get that.

If they reply with anger, maybe it will be a chance to reopen a dialogue. If so, family therapy could be an approach useful for all concerned, if they are willing. Chances are, you all have things that you’d all benefit from talking about in a calm, professional, moderated, neutral environment.

You might also benefit from a book we reviewed previously, “Parent Effectiveness Training”. This may seem like “shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted”, but in fact it’s a very good guide to relationship dynamics in general, and extensively covers relations between parents and adult children.

If they don’t reply, then, you did your part. Take solace in knowing that much.

Some final thoughts:

At the end of the day, as parents, our kids living well is (hopefully) testament to that we prepared them well for life, and sometimes, being a parent is a thankless task.

But, we (hopefully) didn’t become parents for the plaudits, after all.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Blue Light At Night? Save More Than Just Your Sleep!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Beating The Insomnia Blues

You previously asked us about recipes for insomnia (or rather, recipes/foods to help with easing insomnia). We delivered!

But we also semi-promised we’d cover a bit more of the general management of insomnia, because while diet’s important, it’s not everything.

Sleep Hygiene

Alright, you probably know this first bit, but we’d be remiss if we didn’t cover it before moving on:

- No caffeine or alcohol before bed

- Ideally: none earlier either, but if you enjoy one or the other or both, we realize an article about sleep hygiene isn’t going to be what changes your mind

- Fresh bedding

- At the very least, fresh pillowcase(s). While washing and drying an entire bedding set constantly may be arduous and wasteful of resources, it never hurts to throw your latest pillowcase(s) in with each load of laundry you happen to do.

- Warm bed, cool room = maximum coziness

- Dark room. Speaking of which…

About That Darkness…

When we say the room should be dark, we really mean it:

- Not dark like “evening mood lighting”, but actually dark.

- Not dark like “in the pale moonlight”, but actually dark.

- Not dark like “apart from the light peeking under the doorway”, but actually dark.

- Not dark like “apart from a few LEDs on electronic devices that are on standby or are charging”, but actually dark.

There are many studies about the impact of blue light on sleep, but here’s one as an example.

If blue light with wavelength between 415 nm and 455 nm (in the visible spectrum) hits the retina, melatonin (the sleep hormone) will be suppressed.

The extent of the suppression is proportional to the amount of blue light. This means that there is a difference between starting at an “artificial daylight” lamp, and having the blue LED of your phone charger showing… but the effect is cumulative.

And it gets worse:

❝This high energy blue light passes through the cornea and lens to the retina causing diseases such as dry eye, cataract, age-related macular degeneration, even stimulating the brain, inhibiting melatonin secretion, and enhancing adrenocortical hormone production, which will destroy the hormonal balance and directly affect sleep quality.❞

Read it in full: Research progress about the effect and prevention of blue light on eyes

See also: Age-related maculopathy and the impact of blue light hazard

So, what this means, if we value our health, is:

- Switch off, or if that’s impractical, cover the lights of electronic devices. This might be as simple as placing your phone face-down rather than face-up, for instance.

- Invest in blackout blinds/curtains (per your preference). Serious ones, like these ← see how they don’t have to be black to be blackout! You don’t have to sacrifice style for function

- If you can’t reasonably do the above, consider a sleep mask. Again, a good one. Not the kind you were given on a flight, or got free with some fluffy handcuffs. We mean a full-blackout sleep mask that’s designed to be comfortable enough to sleep in, like this one.

- If you need to get up to pee or whatever, do like a pirate and keep one eye covered/closed. That way, it’ll remain unaffected by the light. Pirates did it to retain their night vision when switching between being on-deck or below, but you can do it to halve the loss of melatonin.

Lights-Out For Your Brain Too

You can have all the darkness in the world and still not sleep if your mind is racing thinking about:

- your recent day

- your next day

- that conversation you wish had gone differently

- what you really should have done when you were 18

- how you would go about fixing your country’s socio-political and economic woes if you were in charge

- Etc.

We wrote about how to hit pause on all that, in a previous edition of 10almonds.

Check it out: The Off-Button For Your Brain—How to “just say no” to your racing mind (this trick really works)

Sweet dreams!

Share This Post

- No caffeine or alcohol before bed

-

Knee Cracking & Popping: Should You Be Worried?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Tom Walters (Doctor of Physical Therapy) explains about what’s going on behind our musical knees, and whether or not this synovial symphony is cause for concern.

When to worry (and when not to)

If the clicking/cracking/popping/etc does not come with pain, then it is probably being caused by the harmless movement of fluid within the joints, in this case specifically the patellofemoral joint, just behind the kneecap.

As Dr. Walters says:

❝It is extremely important that people understand that noises from the knee are usually not associated with pathology and may actually be a sign of a healthy, well-lubricated joint. let’s be careful not to make people feel bad about their knee noise as it can negatively influence how they view their body!❞

On the other hand, there is also such a thing as patellofemoral joint pain syndrome (PFPS), which is very common, and involves pain behind the kneecap, especially upon over-stressing the knee(s).

In such cases, it is good to get that checked out by a doctor/physiotherapist.

Dr. Walters advises us to gradually build up strength, and not try for too much too quickly. He also advises us to take care to strengthen our glutes in particular, so our knees have adequate support. Gentle stretching of the quadriceps and soft tissue mobilization with a foam roller, are also recommended, to reduce tension on the kneecap.

For more on these things and especially about the exercises, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

How To Really Take Care Of Your Joints

Take care!

Share This Post

-

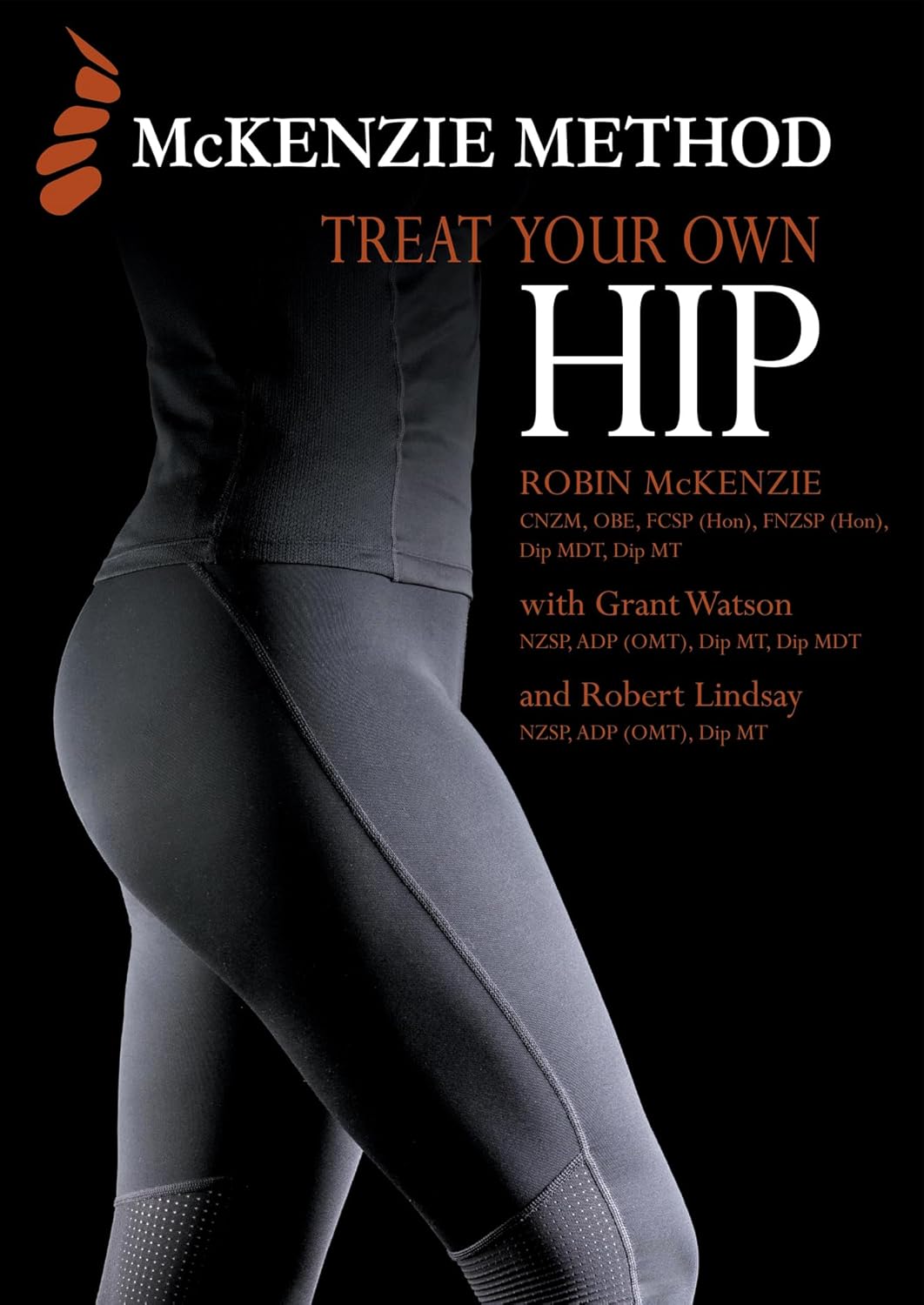

Treat Your Own Hip – by Robin McKenzie

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We previously reviewed another book by this author in this series, “Treat Your Own Knee”, and today it’s the same deal, but for the hip.

A quick note about the author first: a physiotherapist and not a doctor, but with over 40 years of practice to his name and 33 letters after his name (CNZM OBE FCSP (Hon) FNZSP (Hon) Dip MDT Dip MT), he seems to know his stuff.

He takes the reader through first diagnosing the nature of the pain (and how to rule out, for example, a back problem manifesting as hip pain, rather than a hip problem per se—and points to his own “Treat Your Own Back” manual if it turns out that that’s your problem instead), and then treating it. A bold claim, the kind that many people’s lawyers don’t let them make, but once again, this guy is pretty much the expert when it comes to this. Ask any other physiotherapist, and they probably have several of his books on their shelf.

The treatments recommend are tailored to the results of various diagnostic flowcharts; essentially troubleshooting your hip. However, they mainly consist of exercises (perhaps the greatest value of the book), and lifestyle adjustments (these ones, 10almonds readers probably know already, but a reminder never hurts).

The explanations are thorough while still being comprehensible, and there is zero sensationalization or fluff. It is straight to the point, and clearly illustrated too with diagrams and photographs.

Bottom line: if you’re looking for a “one-stop shop” for diagnosing and treating your bad hip, then this is it.

Click here to check out Treat Your Own Hip, and indeed Treat Your Own Hip!

PS: if you have musculoskeletal problems elsewhere in your body, you might want to check out the rest of his body parts series (neck, back, shoulder, wrist, knee, ankle) for the one that’s tailored to your specific problem.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Ready… Set… Flow!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Time to make your new year plans? Or maybe you’ve already made a list, and you’re checking it twice. If so, now’s the time to make sure that your new year’s plans will flow:

“Flow”, as you may be aware, is the psychological state generally defined as “a state in which we feel good about what we’re doing, and just keep doing it, at a peak performance level”; the term was coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and has risen to popularity since.

We wrote about it a little before, here:

Morning Routines That Just Flow

The above article details how to start the perfect day, but how to start the perfect year? Firstly, it’s good to get the jump on the new year a little; see:

The Science Of New Year’s Pre-Resolutions

…and we also agree with Dr. Faye Bate, who preaches taking the path of least resistance when it comes to healthy habits:

How To Actually Start A Healthy Lifestyle In The New Year

Because…

Getting into the flow

The most hydrating drink is the one that [contains adequate water and] you will actually drink. The best exercise is the one you’ll do. The best sleep is the sleep you can actually get. And so on.

We see this—or rather its evil counterpoint—a lot in diet culture. People frame their willpower against the temptations of donuts and whatever, and make Faustian bargains whereby they will eat food they find boring in the hopes it will bring them good health. And it won’t. Because, they’ll give up quickly.

Instead, each part of our healthy life has to be engaged with with a sense of flow. Again, that’s: “a state in which we feel good about what we’re doing, and just keep doing it, at a peak performance level”

So we need to find healthy recipes we like (check out our recipe section!), we need to find exercise that we like, we need to find an approach to sleep that the Geneva Convention wouldn’t consider a kind a torture, and so forth. And, ideally, not just “like” in the sense of “this is tolerable” but “like” in the sense of “I am truly passionate about this thing”.

And that’s going to look different for each of us.

Running is a great example of something that some people truly love, whereas others will do almost anything to avoid.

And food? We’ve written before about the usefulness of a “to don’t” list; it’s like a “to do” list, but it’s things we’re not going to even try to do. For example, a person with two addictions is usually advised to quit one at a time, so quitting the other would go on a “to don’t” list for now. The same goes for food; you need to enjoy what you’re eating or you won’t “feel good about what we’re doing, and just keep doing it”, per flow. So, do not deprive yourself; it won’t work anyway; just pick one healthy change to make, and then queue up any other changes for once the first one has started feeling natural to you.

For more on “to don’t” lists and other such tricks, see: How To Keep On Keeping On… Long Term!

Staying in the flow

…is not usually a problem, you would think, because “…and just keep doing it, at peak performance level” but the fact is, sometimes we get kicked out of our flow by something external. We covered some of that in the above-linked “How To Keep On Keeping On” article, such as figuring out showstoppers in advance (for example, “if I get an injury, I will rest until it is healed”) and ideally, back-up plans.

For example, let’s say you have your dietary plan all worked out, then you are invited to someone’s birthday celebration a couple of weeks in, and you don’t want to rain on their parade, so you figure out for yourself in advance how you are going to mitigate any harm to your plans, e.g. “I will simply choose the healthiest option available, and not worry if it doesn’t meet my usual standards” or “I will simply fast” if that’s an appropriate thing for you (for some it might be, for some it might not be).

For more on this, see:

How To Avoid Slipping Into (Bad) Old Habits

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Lacking Motivation? Science Has The Answer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Science Of Motivation (And How To Use It To Your Advantage)

When we do something rewarding, our brain gets a little (or big!) spike of dopamine. Dopamine is popularly associated with pleasure—which is fair— but there’s more to it than this.

Dopamine is also responsible for motivation itself, as a prime mover before we do the thing that we find rewarding. If we eat a banana, and enjoy it, perhaps because our body needed the nutrients from it, our brain gets a hit of dopamine.

(and not because bananas contain dopamine; that dopamine is useful for the body, but can’t pass the blood-brain barrier to have an effect on the brain)

So where does the dopamine in our brain come from? That dopamine is made in the brain itself.

Key Important Fact: the brain produces dopamine when it expects an activity to be rewarding.

If you take nothing else away from today’s newsletter, let it be this!

It makes no difference if the activity is then not rewarding. And, it will keep on motivating you to do something it anticipated being rewarding, no matter how many times the activity disappoints, because it’ll remember the very dopamine that it created, as having been the reward.

To put this into an example:

- How often have you spent time aimlessly scrolling social media, flitting between the same three apps, or sifting through TV channels when “there’s nothing good on to watch”?

- And how often did you think afterwards “that was a good and rewarding use of my time; I’m glad I did that”?

In reality, whatever you felt like you were in search of, you were really in search of dopamine. And you didn’t find it, but your brain did make some, just enough to keep you going.

Don’t try to “dopamine detox”, though.

While taking a break from social media / doomscrolling the news / mindless TV-watching can be a great and healthful idea, you can’t actually “detox” from a substance your body makes inside itself.

Which is fortunate, because if you could, you’d die, horribly and miserably.

If you could “detox” completely from dopamine, you’d lose all motivation, and also other things that dopamine is responsible for, including motor control, language faculties, and critical task analysis (i.e. planning).

This doesn’t just mean that you’d not be able to plan a wedding; it also means:

- you wouldn’t be able to plan how to get a drink of water

- you wouldn’t have any motivation to get water even if you were literally dying of thirst

- you wouldn’t have the motor control to be able to physically drink it anyway

Read: Dopamine and Reward: The Anhedonia Hypothesis 30 years on

(this article is deep and covers a lot of ground, but is a fascinating read if you have time)

Note: if you’re wondering why that article mentions schizophrenia so much, it’s because schizophrenia is in large part a disease of having too much dopamine.

Consequently, antipsychotic drugs (and similar) used in the treatment of schizophrenia are generally dopamine antagonists, and scientists have been working on how to treat schizophrenia without also crippling the patient’s ability to function.

Do be clever about how you get your dopamine fix

Since we are hardwired to crave dopamine, and the only way to outright quash that craving is by inducing anhedonic depression, we have to leverage what we can’t change.

The trick is: question how much your motivation aligns with your goals (or doesn’t).

So if you feel like checking Facebook for the eleventieth time today, ask yourself: “am I really looking for new exciting events that surely happened in the past 60 seconds since I last checked, or am I just looking for dopamine?”

You might then realize: “Hmm, I’m actually just looking for dopamine, and I’m not going to find it there”

Then, pick something else to do that will actually be more rewarding. It helps if you make a sort of dopa-menu in advance, of things to pick from. You can keep this as a list on your phone, or printed and pinned up near your computer.

Examples might be: Working on that passion project of yours, or engaging in your preferred hobby. Or spending quality time with a loved one. Or doing housework (surprisingly not something we’re commonly motivated-by-default to do, but actually is rewarding when done). Or exercising (same deal). Or learning that language on Duolingo (all those bells and whistles the app has are very much intentional dopamine-triggers to make it addictive, but it’s not a terrible outcome to be addicted to learning!).

Basically… Let your brain’s tendency to get led astray work in your favor, by putting things in front of it that will lead you in good directions.

Things for your health and/or education are almost always great things to allow yourself the “ooh, shiny” reaction and pick them up, try something new, etc.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Policosanol: A Rival To Statins, Without The Side Effects?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Policosanol (which can be extracted from various sources, but is mostly made from sugar cane extract) is marketed as lipid-lowering agent for improving cholesterol levels, but its research history has not been without controversy:

2001: it works!

After a lot of research in the 1990s, it came out of the gate strong in 2001, with:

❝Policosanol (5 and 10 mg/day) significantly decreased LDL-cholesterol (17.3% and 26.7%, respectively), total cholesterol (12.9% and 19.5%), as well as the ratios of LDL-cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol (17.2% and 26.5%) and total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol (16.3% and 21.0%) compared with baseline and placebo❞

This, by the way, is comparable in efficacy to the most powerful statins, but without the adverse side effects.

Source: Efficacy and tolerability of policosanol in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women

Furthermore, its effects were not limited to postmenopausal women, and additionally, it was found that 20mg/day was sufficient for optimal effects; 40mg worked exactly the same as 20mg:

2006–2010: we do not trust the Cubans!

After it had been marketed and used in much of the world for some years, extra scrutiny was brought upon it, because the initial studies had been performed by the same lab in Cuba, a commercial lab that had tested them for a private interest (i.e., a company selling the supplement):

Heart Beat: Policosanol: A sweet nothing for high cholesterol

And furthermore, US-based labs were unable to replicate the results:

Policosanols as Nutraceuticals: Fact or Fiction

The Cuban researchers countered that the composition of policosanol as produced in their lab was different than the composition of the policosanol as produced in the US labs, because of the purity of the ingredients used in the Cuban lab.

Which, on the face of it, could be true or could just be the claim of a commercial lab with an association with a company selling a product.

Of course, importing Cuban ingredients to test them in the US was not a reasonably accessible option for the US-based labs, because of the US’s embargo of Cuba. In principle it could be done, but unless there is already a huge clear profit incentive, research scientists are usually on their hands and knees begging for grants already, so getting extra funding for specially-important Cuban ingredients was not going to be likely.

2012: never mind, it does work after all!

An American meta-analysis of 4596 patients from 52 eligible studies (from around the world, so many of them not affected by the US’s embargo; some were from within the US using non-Cuban ingredients, though), found:

❝policosanol is more effective than plant sterols and stanols for LDL level reduction and more favorably alters the lipid profile, approaching antilipemic drug efficacy❞

Those last words there, to be clear, mean “yes, the original claim of being on a par with statins is at least more or less true”.

Source: Meta-Analysis of Natural Therapies for Hyperlipidemia: Plant Sterols and Stanols versus Policosanol

2018: also yes, the Cuban kind does get those extra-effective results, even when tested outside of Cuba

A Korean research team verified this; it’s quite straightforward so for brevity we’ll just drop links:

- Consumption of Cuban Policosanol Improves Blood Pressure and Lipid Profile via Enhancement of HDL Functionality in Healthy Women Subjects: Randomized, Double-Blinded, and Placebo-Controlled Study

- Long-Term Consumption of Cuban Policosanol Lowers Central and Brachial Blood Pressure and Improves Lipid Profile With Enhancement of Lipoprotein Properties in Healthy Korean Participants

Mystery resolved!

Want to try some?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon—it’s not the Cuban kind, because the US’s trade embargo makes it difficult for the US to import even things that are theoretically now exempt from the embargo such as food and medicines. In principle they can now be imported, but in practice, the extra regulations added to Cuban imports make it nearly impossible, especially for small sellers.

Still, it’s 40mg/tablet policosanol from sugar cane extract, and 3rd party lab tested, so it’s the next best thing 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: