Great Sex Never Gets Old – by Kimberly Cunningham – by Kimberly Cunningham

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Here some readers may be thinking “after 40? But I am 70 already” or such, so be assured, there’s no upper limit on the applicability of this book’s writings. The number of 40 was chosen more as the start point of things, because it is an age after which the majority of hormonal declines happen (and with them, often, sex drive and/or physical ability). But, as she explains, this is by no means necessarily an end, and can instead be an exciting new beginning.

She kicks things off with a “wellness check”, before diving into the science of the menopause—and yes, the andropause too.

She doesn’t stop there though, and discusses other hormones besides the obvious ones, and other non-hormonal factors that can affect sex in what for most people is the later half of life.

Nurse Cunningham, much like most of modern science, is strongly pro-HRT, and/but doesn’t claim it to be a magic bullet (though honestly, it can feel like it is! But here we’re reviewing the book, not HRT, so let’s continue), or else this book could have been a leaflet. Instead, she talks about the side-effects to expect (mostly good or neutral, but still, things you don’t want to be taken by surprise by), and what things will just be “a little different” now if you’re running on exogenous bioidentical hormones rather than ones your own body made. A lot of this comes down to how and when one takes them, by the way, since this can be different to your body making its own natural peaks and troughs.

But it’s not all about hormones; there are also plenty of chapters on social and psychological issues, as well as medical issues other than hormones.

The style is very light and conversational, while also casually dropping about 30 pages of scientific references. Like many nurses, the author knows at least as much as doctors when it comes to her area of expertise, and it shows.

Bottom line: if your sex has ever hit a slump, and/or you simply recognize that it could, this book could make a very important difference.

Click here to check out Great Sex Never Gets Old, and enjoy the best of life in the bedroom too!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Art Of Letting Go – by Nick Trenton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may be wondering: is this a basic CBT book? And, for the most part, no, it’s not.

It does touch on some of the time-tested CBT techniques, but a large part of the book is about reframing things in a different way, that’s a little more DBT-ish, and even straying into BA. But enough of the initialisms, let’s give an example:

It can be scary to let go of the past, or of present or future possibilities (bad ones as well as good!). However, it’s hard to consciously do something negative (same principle as “don’t think of a pink elephant”), so instead, look at it as taking hold of the present/future—and thus finding comfort and security in a new reality rather than an old memory or a never-actual imagining.

So, this book has a lot of ideas like that, and if even one of them helps, then it was worth reading.

The writing style is comprehensive, and goes for the “tell them what you’re gonna tell them; tell them; then tell them what you told them” approach, which a) is considered good for learning b) can feel a little like padding nonetheless.

Bottom line: this reviewer didn’t personally love the style, but the content made up for it.

Share This Post

-

Oral vaccines could provide relief for people who suffer regular UTIs. Here’s how they work

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In a recent TikTok video, Australian media personality Abbie Chatfield shared she was starting a vaccine to protect against urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Huge news for the UTI girlies. I am starting a UTI vaccine tonight for the first time.

Chatfield suffers from recurrent UTIs and has turned to the Uromune vaccine, an emerging option for those seeking relief beyond antibiotics.

But Uromune is not a traditional vaccine injected to your arm. So what is it and how does it work?

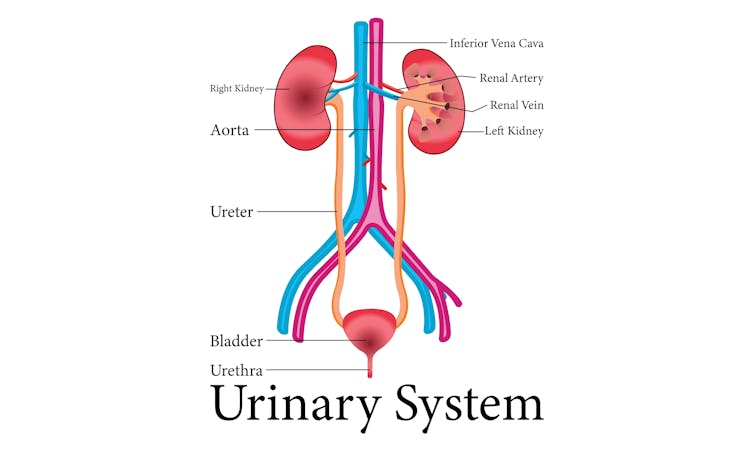

9nong/Shutterstock First, what are UTIs?

UTIs are caused by bacteria entering the urinary system. This system includes the kidneys, bladder, ureters (thin tubes connecting the kidneys to the bladder), and the urethra (the tube through which urine leaves the body).

The most common culprit is Escherichia coli (E. coli), a type of bacteria normally found in the intestines.

While most types of E. coli are harmless in the gut, it can cause infection if it enters the urinary tract. UTIs are particularly prevalent in women due to their shorter urethras, which make it easier for bacteria to reach the bladder.

Roughly 50% of women will experience at least one UTI in their lifetime, and up to half of those will have a recurrence within six months.

UTIs are caused by bacteria enterning the urinary system. oxo7051/Shutterstock The symptoms of a UTI typically include a burning sensation when you wee, frequent urges to go even when the bladder is empty, cloudy or strong-smelling urine, and pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen or back. If left untreated, a UTI can escalate into a kidney infection, which can require more intensive treatment.

While antibiotics are the go-to treatment for UTIs, the rise of antibiotic resistance and the fact many people experience frequent reinfections has sparked more interest in preventive options, including vaccines.

What is Uromune?

Uromune is a bit different to traditional vaccines that are injected into the muscle. It’s a sublingual spray, which means you spray it under your tongue. Uromune is generally used daily for three months.

It contains inactivated forms of four bacteria that are responsible for most UTIs, including E. coli. By introducing these bacteria in a controlled way, it helps your immune system learn to recognise and fight them off before they cause an infection. It can be classified as an immunotherapy.

A recent study involving 1,104 women found the Uromune vaccine was 91.7% effective at reducing recurrent UTIs after three months, with effectiveness dropping to 57.6% after 12 months.

These results suggest Uromune could provide significant (though time-limited) relief for women dealing with frequent UTIs, however peer-reviewed research remains limited.

Any side effects of Uromune are usually mild and may include dry mouth, slight stomach discomfort, and nausea. These side effects typically go away on their own and very few people stop treatment because of them. In rare cases, some people may experience an allergic reaction.

How can I access it?

In Australia, Uromune has not received full approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), and so it’s not something you can just go and pick up from the pharmacy.

However, Uromune can be accessed via the TGA’s Special Access Scheme or the Authorised Prescriber pathway. This means a GP or specialist can apply for approval to prescribe Uromune for patients with recurrent UTIs. Once the patient has a form from their doctor documenting this approval, they can order the vaccine directly from the manufacturer.

Antibiotics are the go-to treatment for UTIs – but scientists are looking at options to prevent them in the first place. Photoroyalty/Shutterstock Uromune is not covered under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, meaning patients must cover the full cost out-of-pocket. The cost of a treatment program is around A$320.

Uromune is similarly available through special access programs in places like the United Kingdom and Europe.

Other options in the pipeline

In addition to Uromune, scientists are exploring other promising UTI vaccines.

Uro-Vaxom is an established immunomodulator, a substance that helps regulate or modify the immune system’s response to bacteria. It’s derived from E. coli proteins and has shown success in reducing UTI recurrences in several studies. Uro-Vaxom is typically prescribed as a daily oral capsule taken for 90 days.

FimCH, another vaccine in development, targets something called the adhesin protein that helps E. coli attach to urinary tract cells. FimCH is typically administered through an injection and early clinical trials have shown promising results.

Meanwhile, StroVac, which is already approved in Germany, contains inactivated strains of bacteria such as E. coli and provides protection for up to 12 months, requiring a booster dose after that. This injection works by stimulating the immune system in the bladder, offering temporary protection against recurrent infections.

These vaccines show promise, but challenges like achieving long-term immunity remain. Research is ongoing to improve these options.

No magic bullet, but there’s reason for optimism

While vaccines such as Uromune may not be an accessible or perfect solution for everyone, they offer real hope for people tired of recurring UTIs and endless rounds of antibiotics.

Although the road to long-term relief might still be a bit bumpy, it’s exciting to see innovative treatments like these giving people more options to take control of their health.

Iris Lim, Assistant Professor in Biomedical Science, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

How To Really Look After Your Joints

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Other Ways To Look After Your Joints

When it comes to joint health, most people have two quick go-to items:

- Stretching

- Supplements like omega-3 and glucosamine sulfate

Stretching, and specifically, mobility exercises, are important! We’ll have to do a main feature on these sometime soon. But for today, we’ll just say: yes, gentle daily stretches go a long way, as does just generally moving more.

And, those supplements are not without their merits. For example:

- Effect of omega-3 on painful symptoms of patients with osteoarthritis of the synovial joints: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator

Of those, glucosamine sulfate may have an extra benefit in now just alleviating the symptoms, but also slowing the progression of degenerative joint conditions (like arthritis of various kinds). This is something it shares with chondroitin sulfate:

Effect of glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate on the osteoarthritis progression: a meta-analysis

An unlikely extra use for the humble cucumber…

As it turns out, cucumber extract beats glucosamine and chondroitin by 200%, at 1/135th of the dose.

You read that right, and it’s not a typo. See for yourself:

Reduce inflammation, have happier joints

Joint pain and joint degeneration in general is certainly not just about inflammation; there is physical wear-and-tear too. But combatting inflammation is important, and turmeric, which we’ve done a main feature on before, is a potent helper in this regard:

See also: Keep Inflammation At Bay

(a whole list of tips for, well, keeping inflammation at bay)

About that wear-and-tear…

Your bones and joints are made of stuff, and that stuff needs to be replaced. As we get older, the body typically gets worse at replacing it in a timely and efficient fashion. We can help it do its job, by giving it more of the stuff it needs.

And what stuff is that?

Well, minerals like calcium and phosphorus are important, but a lot is also protein! Specifically, collagen. We did a main feature on this before, which is good, as it’d take us a lot of space to cover all the benefits here:

We Are Such Stuff As Fish Are Made Of

Short version? People take collagen for their skin, but really, its biggest benefit is for our bones and joints!

Wrap up warmly and… No wait, skip that.

If you have arthritis, you may indeed “feel it in your bones” when the weather changes. But the remedy for that is not to try to fight it, but rather, to strengthen your body’s ability to respond to it.

The answer? Cryotherapy, with ice baths ranking top:

- Effects of an Exercise Program and Cold-Water Immersion Recovery in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Feasibility Study

- Effectiveness of home-based conventional exercise and cryotherapy on daily living activities in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled clinical trial

- Local Cryotherapy, Comparison of Cold Air and Ice Massage on Pain and Handgrip Strength in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Note that this can be just localized, so for example if the problem joints are your wrists, a washing-up bowl with water and ice will do just nicely.

Note also that, per that last study, a single session will only alleviate the pain, not the disease itself. For that (per the other studies) more sessions are required.

We did a main feature about cryotherapy a while back, and it explains how and why it works:

A Cold Shower A Day Keeps The Doctor Away?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Exercise and Fat Loss (5 Things You Need To Know)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s easy to think “I’ll eat whatever; I can always burn it off later”, and if it’s an odd occasion, then that’s fine; indeed, a fit and healthy body can usually weather small infrequent dietary indiscretions easily. But…

You can’t outrun a bad diet

Exercise can create a calorie deficit, but over time, the body balances this out by adjusting one’s metabolism, leading to a plateau in fat loss—and as you might know, you can’t out-exercise a bad diet. On the contrary, dietary adjustments are crucial for fat loss and body recomposition.

About that calorie deficit in the first place, by the way: extreme calorie deficits through exercise alone can lead to muscle loss, reduced energy, and thus sabotage long-term fat loss because having muscle mass increases one’s base metabolic rate (while having fat does not).

Another thing to bear in mind about exercise is that longer workouts without adequate rests in between can cause burnout, injury, or weight gain due to the body doing its best to conserve energy.

So, a good diet is a necessary condition for both muscle maintenance and fat loss.

Five Key Diet Tips:

- Include foods you love: don’t feel obliged cut out favorite foods that are a little unhealthy; incorporate them in moderation for sustainability.

- Keep adjustments small: avoid making drastic dietary changes all at once; make gradual tweaks to prevent feeling deprived.

- Prioritize protein: focus on including a protein source in every meal to increase satiety and aid in muscle building.

- Avoid low-calorie diets: drastically cutting calories can lead to muscle loss, metabolic adaptation, and overeating.

- Embrace diet evolution: changes may not feel sustainable at first, but adjustments over time help achieve long-term balance. You can always “adjust course” as you go.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Are You A Calorie-Burning Machine?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Brown Rice vs Russet Potatoes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing brown rice to russet potatoes, we picked the rice.

Why?

First we’ll note: for brevity and to avoid undue repetitiveness, we’re henceforth going to just say “rice” and “potato”, respectively, but values and conclusions are still for brown rice and russet potatoes. Also, we are including the flesh and skin into the metrics for the potato (without the skin, many nutrients are no longer present).

In terms of macros, the rice has more fiber, carbs, and protein. It’s difficult to compare glycemic indices in this case, because they both need cooking before eating, and how one cooks them (and whether one cools them) along with other preparatory methods will change the GI considerably. Thus, we’ll simply go with the more nutritionally dense option, and that’s the rice.

In the category of vitamins, the rice has much more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, E, and choline, while the potato has more of vitamins C and K. A clear win for rice (and by the way, that’s 60x the vitamin E, but as potatoes don’t have much vitamin E, in practical terms, it’s actually the B-vitamins where rice’s strengths really show, as potatoes aren’t a bad source but rice is amazing).

When it comes to minerals, rice has a lot more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while potato has more calcium and potassium. Another easy win for rice.

You may be wondering about phytic acid: brown rice contains this by default, and it is something of an antinutrient (i.e., if left as-is, it reduces the bioavailability of other nutrients), and/but the phytic acid content is reduced to negligible by two things: soaking and heating (especially if those two things are combined) ← doing this the way described results in bioavailability of nutrients that’s even better than if there were just no phytic acid, albeit it requires you having the time to soak, and do so at temperature.

All in all, adding up the sections makes for an overall win for brown rice, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Carb-Strong or Carb-Wrong? Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Led by RFK Jr., Conservatives Embrace Raw Milk. Regulators Say It’s Dangerous.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In summertime, cows wait under a canopy to be milked at Mark McAfee’s farm in Fresno, California. From his Cessna 210 Centurion propeller plane, the 63-year-old can view grazing lands of the dairy company he runs that produces products such as unpasteurized milk and cheese for almost 2,000 stores.

Federal regulators say it’s risky business. Samples of raw milk can contain bird flu virus and other pathogens linked to kidney disease, miscarriages, and death.

McAfee, founder and CEO of the Raw Farm, who also leads the Raw Milk Institute, says he plans to soon be in a position to change that message.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the anti-vaccine activist President Donald Trump has tapped to run the Department of Health and Human Services, recruited McAfee to apply for a job as the FDA’s raw milk standards and policy adviser, McAfee said. McAfee has already written draft proposals for possible federal certification of raw dairy farms, he said.

Virologists are alarmed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against unpasteurized dairy that hasn’t been heated to kill pathogens such as bird flu. Interstate raw milk sales for human consumption are banned by the FDA. A Trump administration that weakens the ban or extols raw milk, the scientists say, could lead to more foodborne illness. It could also, they say, raise the risk of the highly pathogenic H5N1 bird flu virus evolving to spread more efficiently, including between people, possibly fueling a pandemic.

“If the FDA says raw milk is now legal and the CDC comes through and says it advises drinking raw milk, that’s a recipe for mass infection,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist and co-editor-in-chief of the medical journal Vaccine and an adjunct professor at Stony Brook University in New York.

The raw milk controversy reflects the broader tensions President Donald Trump will confront when pursuing his second-administration agenda of rolling back regulations and injecting more consumer choice into health care.

Many policies Kennedy has said he wants to revisit — from the fluoridation of tap water to nutrition guidance to childhood vaccine requirements — are backed by scientific research and were established to protect public health. Some physician groups and Democrats are gearing up to fight initiatives they say would put people at risk.

Raw milk has gained a following among anti-regulatory conservatives who are part of a burgeoning health freedom movement.

“The health freedom movement was adopted by the tea party, and conspiracy websites gave it momentum,” said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who has studied the history of the anti-vaccine movement.

Once-fringe ideas are edging into the mainstream. Vaccine hesitancy is growing.

Arkansas, Utah, and Kentucky are weighing legislation that would relax or end requirements for fluoride in public water. And 30 states now allow for the sale of raw milk in some form within their borders.

While only an estimated 3% of the U.S. population consumes raw milk or cheese, efforts to try to restrict its sales have riled Republicans and provided grist for conservative podcasts.

Many conservatives denounced last year’s execution of a search warrant when Pennsylvania agriculture officials and state troopers arrived at an organic farm tucked off a two-lane road on Jan. 4, 2024. State inspectors were investigating cases of two children sickened by E. coli bacteria and sales of raw dairy from the operation owned by Amish farmer Amos Miller, according to a complaint filed by the state’s agricultural department.

Bundled in flannel shirts and winter jackets, the inspectors put orange stickers on products detaining them from sale, and they left toting product samples in large blue-and-white coolers, online videos show. The 2024 complaint against Miller alleged that he and his wife sold dairy products in violation of state law.

The farm was well known to regulators. They say in the complaint that a Florida consumer died after being sickened in 2014 with listeria bacteria found in raw dairy from Miller’s farm. The FDA said a raw milk sample from the farm indicates it was the “likely source” of the infection, based on the complaint.

Neither Miller’s farm nor his lawyer returned calls seeking comment.

The Millers’ attorney filed a preliminary objection that said “shutting down Defendants would cause inequitable harm, exceed the authority of the agency, constitute an excessive fine as well as disparate, discriminatory punishment, and contravene every essential Constitutional protection and powers reserved to the people of Pennsylvania.”

Regulators in Pennsylvania said in a press release they must protect the public, and especially children, from harm. “We cannot ignore the illnesses and further potential harm posed by distribution of these unregulated products,” the Pennsylvania agricultural department and attorney general said in a joint statement.

Unpasteurized dairy products are responsible for almost all the estimated 761 illnesses and 22 hospitalizations in the U.S. that occur annually because of dairy-related illness, according to a study published in the June 2017 issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

But conservatives say raiding an Amish farm is government overreach. They’re “harassing him and trying to make an example of him. Our government is really out of control,” Pennsylvania Republican Sen. Doug Mastriano said in a video he posted to Facebook.

Videos show protesters at a February 2024 hearing on Miller’s case included Amish men dressed in black with straw hats and locals waving homemade signs with slogans such as “FDA Go Away.” A court in March issued a preliminary injunction that barred Miller from marketing and selling raw dairy products within the commonwealth pending appeal, but the order did not preclude sales of raw milk to customers out of state. The case is ongoing.

With Kennedy, the raw milk debate is poised to go national. Kennedy wrote on X in October that the “FDA’s war on public health is about to end.” In the post, he pointed to the agency’s “aggressive suppression” of raw milk, as one example.

McAfee is ready. He wants to see a national raw milk ordinance, similar to one that exists for pasteurized milk, that would set minimal national standards. Farmers could attain certification through training, continuing education, and on-site pathogen testing, with one standard for farms that sell to consumers and another for retail sales.

The Trump administration didn’t return emails seeking comment.

McAfee has detailed the system he developed to ensure his raw dairy products are safe. He confirmed the process for KFF Health News: cows with yellow-tagged ears graze on grass pastures and are cleansed in washing pens before milking. The raw dairy is held back from consumer sale until it’s been tested and found clear of pathogens.

His raw dairy products, such as cheese and milk, are sold by a variety of stores, including health, organic, and natural grocery chains, according to the company website, as well as raw dairy pet products, which are not for human consumption.

He said he doesn’t believe the raw milk he sells could contain or transmit viable bird flu virus. He also said he doesn’t believe regulators’ warnings about raw milk and the virus.

“The pharmaceutical industry is trying to create a new pandemic from bird flu to get their stock back up,” said McAfee, who says he counts Kennedy as a customer. His view is not shared by leading virologists.

In December, the state of California secured a voluntary recall of all his company’s raw milk and cream products due to possible bird flu contamination.

Five indoor cats in the same household died or were euthanized in December after drinking raw milk from McAfee’s farm, and tests on four of the animals found they were infected with bird flu, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Health.

In an unrelated case, Joseph Journell, 56, said three of his four indoor cats drank McAfee’s raw milk. Two fell sick and died, he said. His third cat, a large tabby rescue named Big Boy, temporarily lost the use of his hind legs and had to use a specialized wheelchair device, he said. Urine samples from Big Boy were positive for bird flu, according to a copy of the results from Cornell University and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

McAfee dismissed connections between the cats’ illnesses and his products, saying any potential bird flu virus would no longer be viable by the time his raw milk gets to stores. He also said he believes that any sick cats got bird flu from recalled pet food.

Journell said he has hired a lawyer to try to recover his veterinary costs but remains a staunch proponent of raw milk.

“Raw milk is good for you, just not if it has bird flu in it,” he said. “I do believe in its healing powers.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: