Dealing With Hearing Loss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hearing is important, not only for convenience, but also for cognitive health—as an inability to participate in what for most people is an important part of social life, has been shown to accelerate cognitive decline:

14 Powerful Strategies To Prevent Dementia ← one of them is looking after your hearing

To this end, we’ve written before about ways to retain (or at least slow the loss of) your hearing, here:

But, what if, despite our best efforts, your hearing is declining regardless, or is already impaired in some way?

Working with the hand we’ve been dealt

So, your hearing is bad and/or deteriorating. Assuming you’ve ruled out possibilities of fixing it, the next step is how to manage this new state of affairs.

One thing to seriously consider, sooner than you think you need to, is using hearing aids. This is because they will not only help you in the obvious practical way, but also, they will slow the associated decline of the parts of your brain that process the language you hear:

ACHIEVE study finds hearing aids cut cognitive decline by 48%

…and here’s the paper itself:

Furthermore, hearing aid use can significantly reduce all-cause mortality:

Your ears are not the only organs

Remember, today’s about dealing with hearing loss, not preventing it (for preventing it, see the second link we dropped up top).

With this in mind: do not underestimate the usefulness of learning to lipread.

Lipreading is not a panacea; it has its limitations:

- You can’t lipread an audio-only phonecall, or a podcast, or the radio

- You can’t lipread a video call if the video quality is poor

- You can’t lipread if someone is wearing a mask (as in many healthcare settings)

- You can’t lipread multiple people at once; you have to choose whose mouth to watch (or at least, you will miss the first word(s) each time while switching)

- You can’t lipread during sex if your/their face is somewhere else (may seem like a silly example, but actually communication can be important in sex, and the number of times this writer has had to say “Say again?” in intimate moments is ridiculous)

However, it can also make a huge difference the rest of the time, and can even be a superpower in times/places when other people’s hearing is nullified, such as a noisy environment, or a video call in which someone’s mic isn’t working.

The good news is, it’s really very easy to learn to lipread. There are many valid ways (often involving consciously memorizing mouth-shapes from charts, and then putting them together one by one to build a vocabulary), but this writer recommends a more organic, less effort-intensive approach:

- Choose a video of someone who speaks clearly, and for which video you already know what is being said (such as by using subtitles first, or a transcript, or perhaps the person is delivering a famous speech or reciting a poem that you know well, or it’s your favorite movie that you’ve watched many times).

- Now watch it with the sound off (assuming you do normally have some hearing; if you don’t, then you’re probably ahead of the game here) and just pay close attention to the lips. Do this on repeat; soon you’ll be able to “hear” the sounds as you see them made.

- Now choose a video of someone who speaks clearly, for which video you do not already know what is being said. You’ll probably only get parts of it at first; that’s ok.

- Now learn the rest of what they said in that video (by reading a transcript or such), and use it like you used the first video.

- Now repeat steps 3 and 4 until you are lipreading most people easily unless there is some clear obfuscation preventing you.

This process should not take long, as there are only about 44 phonemes (distinct sounds) in English, and once you’ve learned them, you’re set. If you speak more languages, those same 44 phonemes should cover most of most of them, but if not, just repeat the above process with the next language.

Remember, if you have at least some hearing, then most of the time your lipreading and your hearing are going to be working together, and neither will be as strong without the other—but if necessary, well-practised lipreading can indeed often stand in for hearing when hearing isn’t available.

A note on sign language:

Sign language is great, and cool, and useful. However, it’s only as useful as the people who know it, which means that it’s top-tier in the Deaf community (where people will dodge hearing-related cognitive decline entirely, because their social interaction is predominantly signed rather than spoken), and can be useful with close friends or family members who learn it (or at least learn some), but isn’t as useful in most of the wider world when people don’t know it. But if you do want to learn it, don’t let that hold you back—be the change you want to see!

Most of our readers are American, so here’s a good starting place for American Sign Language ← this is a list of mostly-free resources

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Managing Sibling Relationships In Adult Life

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Managing Sibling Relationships In Adult Life

After our previous main feature on estrangement, a subscriber wrote to say:

❝Parent and adult child relationships are so important to maintain as you age, but what about sibling relationships? Adult choices to accept and move on with healthier boundaries is also key for maintaining familial ties.❞

And, this is indeed critical for many of us, if we have siblings!

Writer’s note: I don’t have siblings, but I do happen to have one of Canada’s top psychologists on speed-dial, and she has more knowledge about sibling relationships than I do, not to mention a lifetime of experience both personally and professionally. So, I sought her advice, and she gave me a lot to work with.

Today I bring her ideas, distilled into my writing, for 10almonds’ signature super-digestible bitesize style.

A foundation of support

Starting at the beginning of a sibling story… Sibling relationships are generally beneficial from the get-go.

This is for reasons of mutual support, and an “always there” social presence.

Of course, how positive this experience is may depend on there being a lack of parental favoritism. And certainly, sibling rivalries and conflict can occur at any age, but the stakes are usually lower, early in life.

Growing warmer or colder

Generally speaking, as people age, sibling relationships likely get warmer and less conflictual.

Why? Simply put, we mature and (hopefully!) get more emotionally stable as we go.

However, two things can throw a wrench into the works:

- Long-term rivalries or jealousies (e.g., “who has done better in life”)

- Perceptions of unequal contribution to the family

These can take various forms, but for example if one sibling earns (or otherwise has) much more or much less than another, that can cause resentment on either or both sides:

- Resentment from the side of the sibling with less money: “I’d look after them if our situations were reversed; they can solve my problems easily; why do they resent that and/or ignore my plight?”

- Resentment from the side of the sibling with more money: “I shouldn’t be having to look after my sibling at this age”

It’s ugly and unpleasant. Same goes if the general job of caring for an elderly parent (or parents) falls mostly or entirely on one sibling. This can happen because of being geographically closer or having more time (well… having had more time. Now they don’t, it’s being used for care!).

It can also happen because of being female—daughters are more commonly expected to provide familial support than sons.

And of course, that only gets exacerbated as end-of-life decisions become relevant with regard to parents, and tough decisions may need to be made. And, that’s before looking at conflicts around inheritance.

So, all that seems quite bleak, but it doesn’t have to be like that.

Practical advice

As siblings age, working on communication about feelings is key to keeping siblings close and not devolving into conflict.

Those problems we talked about are far from unique to any set of siblings—they’re just more visible when it’s our own family, that’s all.

So: nothing to be ashamed of, or feel bad about. Just, something to manage—together.

Figure out what everyone involved wants/needs, put them all on the table, and figure out how to:

- Make sure outright needs are met first

- Try to address wants next, where possible

Remember, that if you feel more is being asked of you than you can give (in terms of time, energy, money, whatever), then this discussion is a time to bring that up, and ask for support, e.g.:

“In order to be able to do that, I would need… [description of support]; can you help with that?”

(it might even sometimes be necessary to simply say “No, I can’t do that. Let’s look to see how else we can deal with this” and look for other solutions, brainstorming together)

Some back-and-forth open discussion and even negotiation might be necessary, but it’s so much better than seething quietly from a distance.

The goal here is an outcome where everyone’s needs are met—thus leveraging the biggest strength of having siblings in the first place:

Mutual support, while still being one’s own person. Or, as this writer’s psychology professor friend put it:

❝Circling back to your original intention, this whole discussion adds up to: siblings can be very good or very bad for your life, depending on tons of things that we talked about, especially communication skills, emotional wellness of each person, and the complexity of challenges they face interdependently.❞

Our previous main feature about good communication can help a lot:

Share This Post

-

Build Muscle (Healthily!)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Do You Have To Gain?

We have previously promised a three-part series about changing one’s weight:

- Losing weight (specifically, losing fat)

- Gaining weight (specifically, gaining muscle)

- Gaining weight (specifically, gaining fat)

And yes, that last one is also something that some people want/need to do (healthily!), and want/need help with that.

There will be, however, no need for a “losing muscle” article, because (even though sometimes a person might have some reason to want to do this), it’s really just a case of “those things we said for gaining muscle? Don’t do those and the muscle will atrophy naturally”.

Here’s the first part: How To Lose Weight (Healthily!)

While some people will want to lose fat, please do be aware that the association between weight loss and good health is not nearly so strong as the weight loss industry would have you believe:

And, while BMI is not a useful measure of health in general, it’s worth noting that over the age of 65, a BMI of 27 (which is in the high end of “overweight”, without being obese) is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality:

BMI and all-cause mortality in older adults: a meta-analysis

Body weight, muscle mass, and protein:

That BMI of 27, or whatever weight you might wish to be, ignores body composition. You’re probably aware that volume-for-volume, muscle weighs more than fat.

You’re also probably aware that if we’re not careful, we tend to lose muscle as we get older. This is known as age-related sarcopenia:

Protein, & Fighting Sarcopenia

Dr. Gabrielle Lyon, our featured expert in the above article, recommends getting at least 1.6g of protein per kg of body weight per day (Americans, divide your weight in pounds by 2.2 to get your weight in kg).

So for example, if you weigh 165lb, that’s 75kg, that’s 1.6×75=120g of protein per day.

There is an upper limit to how much protein per day is healthy, and that limit is probably around 2g of protein per kg of body weight per day:

Protein: How Much Do We Need, Really?

You may be wondering: should we go for animal or plant protein? In which case, the short version is:

- If you only care about muscle growth, any complete sources of protein are fine

- If you care about your general health too, then avoiding red meat is best, but other common protein sources are all fine

- Unprocessed is (unsurprisingly) better than processed in either case

Longer version: Plant vs Animal Protein: Head to Head

What exercises are best for muscle-building?

Of course, different muscles require different exercises, but for all of them, resistance training is what builds muscle the most, and it’s pretty much impossible to build a lot of muscle otherwise.

Check out: Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Prepare to fail!

No, really, prepare to fail. Because while resistance training in general is good for maintaining strong muscles and bones, you will only gain muscle if your current muscle is not enough to do the exercise:

- If you do a heavy resistance exercise without undue difficulty, your muscles will say to each other “Good job, team! That was hard, but luckily we were strong enough; no changes necessary”.

- If you do a heavy resistance exercise to the point where you can no longer do it (called: training to failure), then your muscles will say to each other “Oof, what a task! What we’ve got here is clearly not enough, so we’ll have to add more muscle for next time”.

Safety note: training to failure comes with safety risks. If using free weights or weight machines, please do so under well-trained supervision. If doing it with bodyweight (e.g. press-ups until you can press no more) or resistance bands, please check with your doctor first to ensure this is safe for you.

You can also increase the effectiveness of your resistance training by doing it in a way that “confuses” your muscles, making it harder for them to adapt in the moment, and thus forcing them to adapt more in the long term (e.g. get bigger and stronger):

HIIT, But Make It HIRT: High Intensity Resistance Training

Make time for recovery

While many kinds of exercise can be done daily, exercise to build muscle(s) means at the very least resting that muscle (or muscle group) the next day.

For this reason, a lot of bodybuilders have for example a week’s schedule that might look like:

- Monday: Upper body training

- Wednesday: Lower body training

- Friday: Core strength training

…and rest on other days. This gives most muscles a full week of recovery, and every muscle at least 48 hours of recovery.

Note: bodybuilders, like children (who are also doing a lot of body-building, in their own way) need more sleep in order to allow for this recovery and growth to occur. Serious bodybuilders often aim for 12 hours sleep per day. This might be impractical, undesirable, or even impossible for some people, but it’s a factor to be borne in mind and not forgotten.

See also:

Overdone It? How To Speed Up Recovery After Exercise (According To Actual Science)

Anything else that can (safely and healthily) be done to promote muscle growth?

There are a lot of supplements on the market; some are healthy and helpful, other not so much. Here are some we’ve written about:

- What To Eat, Take, And Do Before A Workout

- Creatine: Very Different For Young & Old People

- Ginseng: Exercising With Less Soreness!

- Taurine’s Benefits For Heart Health And More

- Topping Up Testosterone? What To Consider

Take care!

Share This Post

-

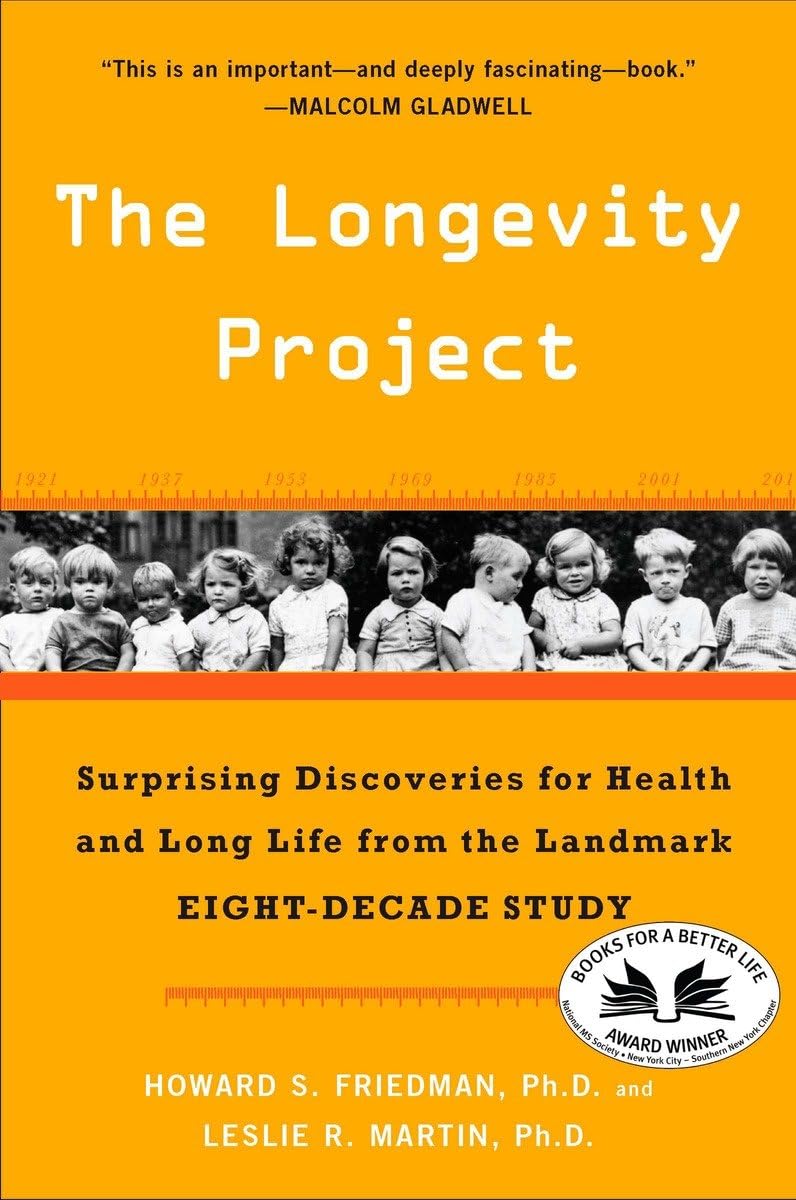

The Longevity Project – by Dr. Howard Friedman & Dr. Leslie Martin

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most books on the topic of longevity focus on such things as diet and exercise, and indeed, those are of course important things. But what of psychological and sociological factors?

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Martin look at a landmark longitudinal study, following a large group of subjects from childhood into old age. Looking at many lifestyle factors and life events, they crunched the numbers to see what things really made the biggest impact on healthy longevity.

A strength of the book is that this study had a huge amount of data—a limitation of the book is that it often avoids giving that concrete data, preferring to say “many”, “a majority”, “a large minority”, “some”, and so forth.

However, the conclusions from the data seem clear, and include many observations such as:

- conscientiousness is a characteristic that not only promotes healthy long life, but also can be acquired as time goes by (some “carefree” children became “conscientious” adults)

- resilience is a characteristic that promotes healthy long life—but tends to only be “unlocked” by adversity

- men tend to live longer if married—women, not so much

- religion and spirituality are not big factors in healthy longevity—but social connections (that may or may not come with such) do make a big difference

Bottom line: if you’d like to know which of your decisions are affecting your healthy longevity (beyond the obvious diet, exercise, etc), this is a great book for collating that information and presenting, in essence, a guideline for a long healthy life.

Click here to check out The Longevity Project and see how it applies to your life!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Biohack Your Way to Healthy Skin – by Jennifer Sun

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The author, an aesthetician with a biotech background, explains about the overlap of skin health and skin beauty, making it better from the inside first (diet and other lifestyle factors), and then tweaking things as desired from the outside.

We previous reviewed another book of hers, “Unleashing Your Best Skin”, and this time the focus is on things you can do at home—not requiring expensive salon treatments (the other book covers both approaches; this one simply skips the clinic work and instead has a lot more detail in the at-home category).

As for what she covers, it comes in categories:

- Gadgets to consider investing in, how to pick good ones, and what gadgets to avoid

- Basic skincare knowledge and practice; here we’re talking cleaners, tonics, moisturizers, and so forth

- Best topical and oral ingredients for the skin (and in contrast, ingredients to be wary of)

- Nutrition for skincare; not just “your skin needs these ingredients”, but also…

- Gut health for skincare, which gets a whole chapter just for that

- Biohacking hormones for skincare, including in the cases of various common hormone imbalances (e.g. menopause, PCOS, etc) and other complications not generally thought of in terms of skincare, such as diabetes and hypo-/hyperthyroidism.

- Circulatory health for skincare (blood and lymph)

- Mental health techniques for skincare (including improving sleep, managing stress, supplements to consider, etc).

As with her other book that we reviewed, the book is broadly aimed at women, and the section on sex-hormonal considerations is completely aimed at women, but as for the rest of the book, there’s no pressing reason why this book couldn’t benefit men too. It also addresses considerations when it comes to darker skintones, something that a lot of similar books overlook.

The style is directly instructional, albeit light and conversational in tone, and still with 20+ pages of scientific references to show that she does indeed know her stuff.

Bottom line: if you’d like to improve your skin health, and/but aren’t a fan of going to the salon, then this book will be an invaluable resource.

Click here to check out Biohack Your Way To Healthy Skin, and biohack your way to healthy skin!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Would a Second Trump Presidency Look Like for Health Care?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

On the presidential campaign trail, former President Donald Trump is, once again, promising to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act — a nebulous goal that became one of his administration’s splashiest policy failures.

“We’re going to fight for much better health care than Obamacare. Obamacare is a catastrophe,” Trump said at a campaign stop in Iowa on Jan. 6.

The perplexing revival of one of Trump’s most politically damaging crusades comes at a time when the Obama-era health law is even more popular and widely used than it was in 2017, when Trump and congressional Republicans proved unable to pass their own plan to replace it. That failed effort was a big part of why Republicans lost control of the House of Representatives in the 2018 midterms.

Despite repeated promises, Trump never presented his own Obamacare replacement. And much of what Trump’s administration actually accomplished in health care has been reversed by the Biden administration.

Still, Trump secured some significant policy changes that remain in place today, including efforts to bring more transparency to prices charged by hospitals and paid by health insurers.

Trying to predict Trump’s priorities in a second term is even more difficult given that he frequently changes his positions on issues, sometimes multiple times.

The Trump campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Perhaps Trump’s biggest achievement is something he rarely talks about on the campaign trail. His administration’s “Operation Warp Speed” managed to create, test, and bring to market a covid-19 vaccine in less than a year, far faster than even the most optimistic predictions.

Many of Trump’s supporters, though, don’t support — and some even vehemently oppose — covid vaccines.

Here is a recap of Trump’s health care record:

Public Health

Trump’s pandemic response dominates his overall record on health care.

More than 400,000 Americans died from covid over Trump’s last year in office. His travel bans and other efforts to prevent the global spread of the virus were ineffective, his administration was slower than other countries’ governments to develop a diagnostic test, and he publicly clashed with his own government’s health officials over the response.

Ahead of the 2020 election, Trump resumed large rallies and other public campaign events that many public health experts regarded as reckless in the face of a highly contagious, deadly virus. He personally flouted public health guidance after contracting covid himself and ending up hospitalized.

At the same time, despite what many saw as a politicization of public health by the White House, Trump signed a massive covid relief bill (after first threatening to veto it). He also presided over some of the largest boosts for the National Institutes of Health’s budget since the turn of the century. And the mRNA-based vaccines Operation Warp Speed helped develop were an astounding scientific breakthrough credited with helping save millions of lives while laying the groundwork for future shots to fight other diseases including cancer.

Abortion

Trump’s biggest contribution to abortion policy was indirect: He appointed three Supreme Court justices, who were instrumental in overturning the constitutional right to an abortion.

During his 2024 campaign, Trump has been all over the place on the red-hot issue. Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, Trump has bemoaned the issue as politically bad for Republicans; criticized one of his rivals, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for signing a six-week abortion ban; and vowed to broker a compromise with “both sides” on abortion, promising that “for the first time in 52 years, you’ll have an issue that we can put behind us.”

He has so far avoided spelling out how he’d do that, or whether he’d support a national abortion ban after any number of weeks.

More recently, however, Trump appears to have mended fences over his criticism of Florida’s six-week ban and more with key abortion opponents, whose support helped him get elected in 2016 — and whom he repaid with a long list of policy changes during his presidency.

Among the anti-abortion actions taken by the Trump administration were a reinstatement of the “Mexico City Policy” that bars giving federal funds to international organizations that support abortion rights; a regulation to bar Planned Parenthood and other organizations that provide abortions from the federal family planning program, Title X; regulatory changes designed to make it easier for health care providers and employers to decline to participate in activities that violate their religious and moral beliefs; and other changes that made it harder for NIH scientists to conduct research using fetal tissue from elective abortions.

All of those policies have since been overturned by the Biden administration.

Health Insurance

Unlike Trump’s policies on reproductive health, many of his administration’s moves related to health insurance still stand.

For example, in 2020, Trump signed into law the No Surprises Act, a bipartisan measure aimed at protecting patients from unexpected medical bills stemming from payment disputes between health care providers and insurers. The bill was included in the $900 billion covid relief package he opposed before signing, though Trump had expressed support for ending surprise medical bills.

His administration also pushed — over the vehement objections of health industry officials — price transparency regulations that require hospitals to post prices and insurers to provide estimated costs for procedures. Those requirements also remain in place, although hospitals in particular have been slow to comply.

Medicaid

While first-time candidate Trump vowed not to cut popular entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, his administration did not stick to that promise. The Affordable Care Act repeal legislation Trump supported in 2017 would have imposed major cuts to Medicaid, and his Department of Health and Human Services later encouraged states to require Medicaid recipients to prove they work in order to receive health insurance.

Drug Prices

One of the issues the Trump administration was most active on was reducing the price of prescription drugs for consumers — a top priority for both Democratic and Republican voters. But many of those proposals were blocked by the courts.

One Trump-era plan that never took effect would have pegged the price of some expensive drugs covered by Medicare to prices in other countries. Another would have required drug companies to include prices in their television advertisements.

A regulation allowing states to import cheaper drugs from Canada did take effect, in November 2020. However, it took until January 2024 for the FDA, under Trump’s successor, to approve the first importation plan, from Florida. Canada has said it won’t allow exports that risk causing drug shortages in that country, leaving unclear whether the policy is workable.

Trump also signed into law measures allowing pharmacists to disclose to patients when the cash price of a drug is lower than the cost using their insurance. Previously pharmacists could be barred from doing so under their contracts with insurers and pharmacy benefit managers.

Veterans’ Health

Trump is credited by some advocates for overhauling Department of Veterans Affairs health care. However, while he did sign a major bill allowing veterans to obtain care outside VA facilities, White House officials also tried to scuttle passage of the spending needed to pay for the initiative.

Medical Freedom

Trump scored a big win for the libertarian wing of the Republican Party when he signed into law the “Right to Try Act,” intended to make it easier for patients with terminal diseases to access drugs or treatments not yet approved by the FDA.

But it is not clear how many patients have managed to obtain treatment using the law because it is aimed at the FDA, which has traditionally granted requests for “compassionate use” of not-yet-approved drugs anyway. The stumbling block, which the law does not address, is getting drug companies to release doses of medicines that are still being tested and may be in short supply.

Trump said in a Jan. 10 Fox News town hall that the law had “saved thousands and thousands” of lives. There’s no evidence for the claim.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

To tackle gendered violence, we also need to look at drugs, trauma and mental health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

After several highly publicised alleged murders of women in Australia, the Albanese government this week pledged more than A$925 million over five years to address men’s violence towards women. This includes up to $5,000 to support those escaping violent relationships.

However, to reduce and prevent gender-based and intimate partner violence we also need to address the root causes and contributors. These include alcohol and other drugs, trauma and mental health issues.

Why is this crucial?

The World Health Organization estimates 30% of women globally have experienced intimate partner violence, gender-based violence or both. In Australia, 27% of women have experienced intimate partner violence by a co-habiting partner; almost 40% of Australian children are exposed to domestic violence.

By gender-based violence we mean violence or intentionally harmful behaviour directed at someone due to their gender. But intimate partner violence specifically refers to violence and abuse occurring between current (or former) romantic partners. Domestic violence can extend beyond intimate partners, to include other family members.

These statistics highlight the urgent need to address not just the aftermath of such violence, but also its roots, including the experiences and behaviours of perpetrators.

What’s the link with mental health, trauma and drugs?

The relationships between mental illness, drug use, traumatic experiences and violence are complex.

When we look specifically at the link between mental illness and violence, most people with mental illness will not become violent. But there is evidence people with serious mental illness can be more likely to become violent.

The use of alcohol and other drugs also increases the risk of domestic violence, including intimate partner violence.

About one in three intimate partner violence incidents involve alcohol. These are more likely to result in physical injury and hospitalisation. The risk of perpetrating violence is even higher for people with mental ill health who are also using alcohol or other drugs.

It’s also important to consider traumatic experiences. Most people who experience trauma do not commit violent acts, but there are high rates of trauma among people who become violent.

For example, experiences of childhood trauma (such as witnessing physical abuse) can increase the risk of perpetrating domestic violence as an adult.

Childhood trauma can leave its mark on adults years later. Roman Yanushevsky/Shutterstock Early traumatic experiences can affect the brain and body’s stress response, leading to heightened fear and perception of threat, and difficulty regulating emotions. This can result in aggressive responses when faced with conflict or stress.

This response to stress increases the risk of alcohol and drug problems, developing PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and increases the risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence.

How can we address these overlapping issues?

We can reduce intimate partner violence by addressing these overlapping issues and tackling the root causes and contributors.

The early intervention and treatment of mental illness, trauma (including PTSD), and alcohol and other drug use, could help reduce violence. So extra investment for these are needed. We also need more investment to prevent mental health issues, and preventing alcohol and drug use disorders from developing in the first place.

Early intervention and treatment of mental illness, trauma and drug use is important. Okrasiuk/Shutterstock Preventing trauma from occuring and supporting those exposed is crucial to end what can often become a vicious cycle of intergenerational trauma and violence. Safe and supportive environments and relationships can protect children against mental health problems or further violence as they grow up and engage in their own intimate relationships.

We also need to acknowledge the widespread impact of trauma and its effects on mental health, drug use and violence. This needs to be integrated into policies and practices to reduce re-traumatising individuals.

How about programs for perpetrators?

Most existing standard intervention programs for perpetrators do not consider the links between trauma, mental health and perpetrating intimate partner violence. Such programs tend to have little or mixed effects on the behaviour of perpetrators.

But we could improve these programs with a coordinated approach including treating mental illness, drug use and trauma at the same time.

Such “multicomponent” programs show promise in meaningfully reducing violent behaviour. However, we need more rigorous and large-scale evaluations of how well they work.

What needs to happen next?

Supporting victim-survivors and improving interventions for perpetrators are both needed. However, intervening once violence has occurred is arguably too late.

We need to direct our efforts towards broader, holistic approaches to prevent and reduce intimate partner violence, including addressing the underlying contributors to violence we’ve outlined.

We also need to look more widely at preventing intimate partner violence and gendered violence.

We need developmentally appropriate education and skills-based programs for adolescents to prevent the emergence of unhealthy relationship patterns before they become established.

We also need to address the social determinants of health that contribute to violence. This includes improving access to affordable housing, employment opportunities and accessible health-care support and treatment options.

All these will be critical if we are to break the cycle of intimate partner violence and improve outcomes for victim-survivors.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. In an emergency, call 000.

Siobhan O’Dean, Postdoctoral Research Associate, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney; Lucinda Grummitt, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney, and Steph Kershaw, Research Fellow, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: