Darwin’s Bed Rest: Worthwhile Idea?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I recall that Charles Darwin (of Evolution fame) used to spend a day a month in bed in order to maintain his physical and psychological equilibrium. Do you see merit in the idea?❞

Well, it certainly sounds wonderful! Granted, it may depend on what you do in bed :p

Descartes did a lot of his work from bed (and also a surprising amount of it while hiding in an oven, but that’s another story), which was probably not so good for the health.

As for Darwin, his health was terrible in quite a lot of ways, so he may not be a great model.

However! Certainly taking a break is well-established as an important and healthful practice:

How To Rest More Efficiently (Yes, Really)

❝I don’t like to admit it but I am getting old. Recently, I had my first “fall” (ominous word!) I was walking across some wet decking and, before I knew what had happened, my feet were shooting forwards, and I crashed to the ground. Luckily I wasn’t seriously damaged. But I was wondering whether you can give us some advice about how best to fall. Maybe there are some good videos on the subject? I would like to be able to practice falling so that it doesn’t come as such a shock when it happens!❞

This writer has totally done the same! You might like our recent main feature on the topic:

…if you’ll pardon the pun

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

The Paleo Diet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s The Real Deal With The Paleo Diet?

The Paleo diet is popular, and has some compelling arguments for it.

Detractors, meanwhile, have derided Paleo’s inclusion of modern innovations, and have also claimed it’s bad for the heart.

But where does the science stand?

First: what is it?

The Paleo diet looks to recreate the diet of the Paleolithic era—in terms of nutrients, anyway. So for example, you’re perfectly welcome to use modern cooking techniques and enjoy foods that aren’t from your immediate locale. Just, not foods that weren’t a thing yet. To give a general idea:

Paleo includes:

- Meat and animal fats

- Eggs

- Fruits and vegetables

- Nuts and seeds

- Herbs and spices

Paleo excludes:

- Processed foods

- Dairy products

- Refined sugar

- Grains of any kind

- Legumes, including any beans or peas

Enjoyers of the Mediterranean Diet or the DASH heart-healthy diet, or those with a keen interest in nutritional science in general, may notice they went off a bit with those last couple of items at the end there, by excluding things that scientific consensus holds should be making up a substantial portion of our daily diet.

But let’s break it down…

First thing: is it accurate?

Well, aside from the modern cooking techniques, the global market of goods, and the fact it does include food that didn’t exist yet (most fruits and vegetables in their modern form are the result of agricultural engineering a mere few thousand years ago, especially in the Americas)…

…no, no it isn’t. Best current scientific consensus is that in the Paleolithic we ate mostly plants, with about 3% of our diet coming from animal-based foods. Much like most modern apes.

Ok, so it’s not historically accurate. No biggie, we’re pragmatists. Is it healthy, though?

Well, health involves a lot of factors, so that depends on what you have in mind. But for example, it can be good for weight loss, almost certainly because of cutting out refined sugar and, by virtue of cutting out all grains, that means having cut out refined flour products, too:

Diet Review: Paleo Diet for Weight Loss

Measured head-to-head with the Mediterranean diet for all-cause mortality and specific mortality, it performed better than the control (Standard American Diet, or “SAD”), probably for the same reasons we just mentioned. However, it was outperformed by the Mediterranean Diet:

So in lay terms: the Paleo is definitely better than just eating lots of refined foods and sugar and stuff, but it’s still not as good as the Mediterranean Diet.

What about some of the health risk claims? Are they true or false?

A common knee-jerk criticism of the paleo-diet is that it’s heart-unhealthy. So much red meat, saturated fat, and no grains and legumes.

The science agrees.

For example, a recent study on long-term adherence to the Paleo diet concluded:

❝Results indicate long-term adherence is associated with different gut microbiota and increased serum trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a gut-derived metabolite associated with cardiovascular disease. A variety of fiber components, including whole grain sources may be required to maintain gut and cardiovascular health.❞

Bottom line:

The Paleo Diet is an interesting concept, and certainly can be good for short-term weight loss. In the long-term, however (and: especially for our heart health) we need less meat and more grains and legumes.

Share This Post

What is childhood dementia? And how could new research help?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Childhood” and “dementia” are two words we wish we didn’t have to use together. But sadly, around 1,400 Australian children and young people live with currently untreatable childhood dementia.

Broadly speaking, childhood dementia is caused by any one of more than 100 rare genetic disorders. Although the causes differ from dementia acquired later in life, the progressive nature of the illness is the same.

Half of infants and children diagnosed with childhood dementia will not reach their tenth birthday, and most will die before turning 18.

Yet this devastating condition has lacked awareness, and importantly, the research attention needed to work towards treatments and a cure.

More about the causes

Most types of childhood dementia are caused by mutations (or mistakes) in our DNA. These mistakes lead to a range of rare genetic disorders, which in turn cause childhood dementia.

Two-thirds of childhood dementia disorders are caused by “inborn errors of metabolism”. This means the metabolic pathways involved in the breakdown of carbohydrates, lipids, fatty acids and proteins in the body fail.

As a result, nerve pathways fail to function, neurons (nerve cells that send messages around the body) die, and progressive cognitive decline occurs.

Childhood dementia is linked to rare genetic disorders. maxim ibragimov/Shutterstock What happens to children with childhood dementia?

Most children initially appear unaffected. But after a period of apparently normal development, children with childhood dementia progressively lose all previously acquired skills and abilities, such as talking, walking, learning, remembering and reasoning.

Childhood dementia also leads to significant changes in behaviour, such as aggression and hyperactivity. Severe sleep disturbance is common and vision and hearing can also be affected. Many children have seizures.

The age when symptoms start can vary, depending partly on the particular genetic disorder causing the dementia, but the average is around two years old. The symptoms are caused by significant, progressive brain damage.

Are there any treatments available?

Childhood dementia treatments currently under evaluation or approved are for a very limited number of disorders, and are only available in some parts of the world. These include gene replacement, gene-modified cell therapy and protein or enzyme replacement therapy. Enzyme replacement therapy is available in Australia for one form of childhood dementia. These therapies attempt to “fix” the problems causing the disease, and have shown promising results.

Other experimental therapies include ones that target faulty protein production or reduce inflammation in the brain.

Research attention is lacking

Death rates for Australian children with cancer nearly halved between 1997 and 2017 thanks to research that has enabled the development of multiple treatments. But over recent decades, nothing has changed for children with dementia.

In 2017–2023, research for childhood cancer received over four times more funding per patient compared to funding for childhood dementia. This is despite childhood dementia causing a similar number of deaths each year as childhood cancer.

The success for childhood cancer sufferers in recent decades demonstrates how adequately funding medical research can lead to improvements in patient outcomes.

Dementia is not just a disease of older people. Miljan Zivkovic/Shutterstock Another bottleneck for childhood dementia patients in Australia is the lack of access to clinical trials. An analysis published in March this year showed that in December 2023, only two clinical trials were recruiting patients with childhood dementia in Australia.

Worldwide however, 54 trials were recruiting, meaning Australian patients and their families are left watching patients in other parts of the world receive potentially lifesaving treatments, with no recourse themselves.

That said, we’ve seen a slowing in the establishment of clinical trials for childhood dementia across the world in recent years.

In addition, we know from consultation with families that current care and support systems are not meeting the needs of children with dementia and their families.

New research

Recently, we were awarded new funding for our research on childhood dementia. This will help us continue and expand studies that seek to develop lifesaving treatments.

More broadly, we need to see increased funding in Australia and around the world for research to develop and translate treatments for the broad spectrum of childhood dementia conditions.

Dr Kristina Elvidge, head of research at the Childhood Dementia Initiative, and Megan Maack, director and CEO, contributed to this article.

Kim Hemsley, Head, Childhood Dementia Research Group, Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University; Nicholas Smith, Head, Paediatric Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Group, University of Adelaide, and Siti Mubarokah, Research Associate, Childhood Dementia Research Group, Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

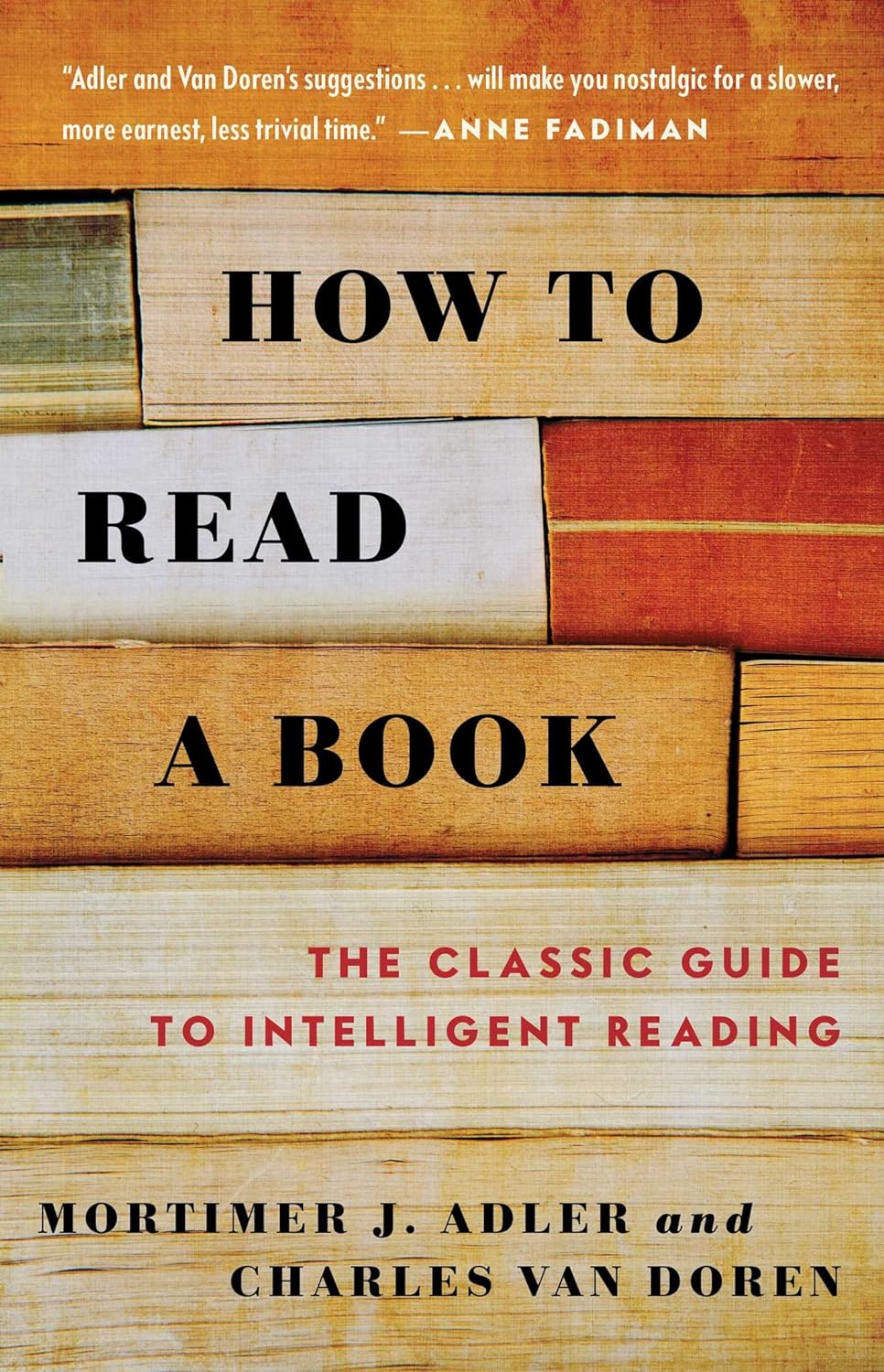

How to Read a Book – by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Are you a cover-to-cover person, or a dip-in-and-out person?

Mortimer Adler and Charles van Doren have made a science out of getting the most from reading books.

They help you find what you’re looking for (Maybe you want to find a better understanding of PCOS… maybe you want to find the definition of “heuristics”… maybe you want to find a new business strategy… maybe you want to find a romantic escape… maybe you want to find a deeper appreciation of 19th century poetry, maybe you want to find… etc).

They then help you retain what you read, and make sure that you don’t miss a trick.

Whether you read books so often that optimizing this is of huge value for you, or so rarely that when you do, you want to make it count, this book could make a real difference to your reading experience forever after.

Share This Post

Related Posts

Evidence doesn’t support spinal cord stimulators for chronic back pain – and they could cause harm

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In an episode of ABC’s Four Corners this week, the use of spinal cord stimulators for chronic back pain was brought into question.

Spinal cord stimulators are devices implanted surgically which deliver electric impulses directly to the spinal cord. They’ve been used to treat people with chronic pain since the 1960s.

Their design has changed significantly over time. Early models required an external generator and invasive surgery to implant them. Current devices are fully implantable, rechargeable and can deliver a variety of electrical signals.

However, despite their long history, rigorous experimental research to test the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulators has only been conducted this century. The findings don’t support their use for treating chronic pain. In fact, data points to a significant risk of harm.

What does the evidence say?

One of the first studies used to support the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulators was published in 2005. This study looked at patients who didn’t get relief from initial spinal surgery and compared implantation of a spinal cord stimulator to a repeat of the spinal surgery.

Although it found spinal cord stimulation was the more effective intervention for chronic back pain, the fact this study compared the device to something that had already failed once is an obvious limitation.

Later studies provided more useful evidence. They compared spinal cord stimulation to non-surgical treatments or placebo devices (for example, deactivated spinal cord stimulators).

A 2023 Cochrane review of the published comparative studies found nearly all studies were restricted to short-term outcomes (weeks). And while some studies appeared to show better pain relief with active spinal cord stimulation, the benefits were small, and the evidence was uncertain.

Only one high-quality study compared spinal cord stimulation to placebo up to six months, and it showed no benefit. The review concluded the data doesn’t support the use of spinal cord stimulation for people with back pain.

What about the harms?

The experimental studies often had small numbers of participants, making any estimate of the harms of spinal cord stimulation difficult. So we need to look to other sources.

A review of adverse events reported to Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration found the harms can be serious. Of the 520 events reported between 2012 and 2019, 79% were considered “severe” and 13% were “life threatening”.

We don’t know exactly how many spinal cord stimulators were implanted during this period, however this surgery is done reasonably widely in Australia, particularly in the private and workers compensation sectors. In 2023, health insurance data showed more than 1,300 spinal cord stimulator procedures were carried out around the country.

In the review, around half the reported harms were due to a malfunction of the device itself (for example, fracture of the electrical lead, or the lead moved to the wrong spot in the body). The other half involved declines in people’s health such as unexplained increased pain, infection, and tears in the lining around the spinal cord.

More than 80% of the harms required at least one surgery to correct the problem. The same study reported four out of every ten spinal cord stimulators implanted were being removed.

Chronic back pain can be debilitating. CGN089/Shutterstock High costs

The cost here is considerable, with the devices alone costing tens of thousands of dollars. Adding associated hospital and medical costs, the total cost for a single procedure averages more than $A50,000. With many patients undergoing multiple repeat procedures, it’s not unusual for costs to be measured in hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Rebates from Medicare, private health funds and other insurance schemes may go towards this total, along with out-of-pocket contributions.

Insurers are uncertain of the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulators, but because their implantation is listed on the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the devices are approved for reimbursement by the government, insurers are forced to fund their use.

Industry influence

If the evidence suggests no sustained benefit over placebo, the harms are significant and the cost is high, why are spinal cord stimulators being used so commonly in Australia? In New Zealand, for example, the devices are rarely used.

Doctors who implant spinal cord stimulators in Australia are well remunerated and funding arrangements are different in New Zealand. But the main reason behind the lack of use in New Zealand is because pain specialists there are not convinced of their effectiveness.

In Australia and elsewhere, the use of spinal cord stimulators is heavily promoted by the pain specialists who implant them, and the device manufacturers, often in unison. The tactics used by the spinal cord stimulator device industry to protect profits have been compared to tactics used by the tobacco industry.

A 2023 paper describes these tactics which include flooding the scientific literature with industry-funded research, undermining unfavourable independent research, and attacking the credibility of those who raise concerns about the devices.

It’s not all bad news

Many who suffer from chronic pain may feel disillusioned after watching the Four Corners report. But it’s not all bad news. Australia happens to be home to some of the world’s top back pain researchers who are working on safe, effective therapies.

New approaches such as sensorimotor retraining, which includes reassurance and encouragement to increase patients’ activity levels, cognitive functional therapy, which targets unhelpful pain-related thinking and behaviour, and old approaches such as exercise, have recently shown benefits in robust clinical research.

If we were to remove funding for expensive, harmful and ineffective treatments, more funding could be directed towards effective ones.

Ian Harris, Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, UNSW Sydney; Adrian C Traeger, Research Fellow, Institute for Musculoskeletal Health, University of Sydney, and Caitlin Jones, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Musculoskeletal Health, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

“You Just Need to Lose Weight” And 19 Other Myths About Fat People – by Aubrey Gordon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed another book by this author, “What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat”, and this time, she’s doing some important mythbusting.

The titular “you just need to lose weight” is a commonly-taken easy-out for many doctors, to avoid having to dispense actual treatment for an actual condition. Whether or not weight loss would help in a given situation is often immaterial; “kicking the can down the road” is the goal.

Most of the book is divided into 20 chapters, each of them devoted to debunking one myth. Think of it like 10almonds’ “Mythbusting Friday” edition (indeed, we did one about obesity), but with an entire book, and as much room as she needs to provide much more detail than we can ever get into in a single article.

And far from being a mere polemic, she does indeed provide that detail—this is clearly a very well-researched book, above and beyond the author’s own personal experience. Further, all the key points are illustrated and articulated clearly, making the book’s ideas very comprehensible.

The style is pop-science, but with frequent bibliographical references for relevant sources.

Bottom line: for some readers, this book will come as a great validation; for others, it may be eye-opening. Either way, it’s a very worthwhile read.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Apple vs Pear – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apple to pear, we picked the pear.

Why?

Both are great! But there’s a category that puts pears ahead of apples…

Looking at their macros first, pears contain more carbs but also more fiber. Both are low glycemic index foods, though.

In the category of vitamins, things are moderately even: apples contain more of vitamins A, B1, B6, and E, while pears contain more of vitamins B3, B9, K, and choline. That’s a 4:4 split, and the two fruits are about equal in the other vitamins they both contain.

When it comes to minerals, pears contain more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. A resounding victory for pears, as apples are not higher in any mineral.

In short, if an apple a day keeps the doctor away, a pear should keep the doctor away for about a day and a half, based on the extra nutrients ← this is slightly facetious as medicine doesn’t work like that, but you get the idea: pears simply have more to offer. Apples are still great though! Enjoy both! Diversity is good.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples To Bees, And High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: