Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

Quick clarification first: today we’re going to be talking about cranberries. Not “cranberry juice drink” that is loaded with sugar, nor “cranberry jelly” or similar that is more added sugar than it is cranberry.

We’re going to keep this short today, because “eat berries” is probably something you know already, but there are some things you should be aware of!

The benefits

Cranberries, even more than most berries, are full of polyphenols and flavonoids that do “those three things that usually come together”: antioxidant properties, anti-inflammatory properties, and anti-cancer properties

Unsurprisingly, this also means they’re good for the immune system and thus quite a boon in flu season:

They’re also good for heart health:

Quick Tip: we’re giving you one study for each of these things for brevity, but if you click through on any of our PubMed study links, you’ll (almost) always see a heading “Similar articles” heading beneath it, which will (almost) always show you plenty more.

Perhaps the most popular reason people take cranberry supplements, though, is their effectiveness at prevention of urinary tract infections:

Indeed, their effectiveness is such that researchers have considered them a putative alternative to antibiotics, particularly in individuals with recurrent UTIs:

Is it safe?

Cranberries are generally considered a very healthful food. However, there are two known possible exceptions:

If you are taking warfarin, it is possible that cranberry consumption may cause additional anti-clotting effects that you don’t want.

If you are at increased risk of kidney stones, the science is currently unclear as to whether this will help or hinder:

- Influence of cranberry juice on the urinary risk factors for calcium oxalate kidney stone formation ← this one concluded “Cranberry juice has antilithogenic properties and, as such, deserves consideration as a conservative therapeutic protocol in managing calcium oxalate urolithiasis”

- Dietary supplementation with cranberry concentrate tablets may increase the risk of nephrolithiasis ← this one, as you can see, concluded the opposite

- Safety of Cranberry: Evaluation of Evidence of Kidney Stone Formation and Botanical Drug-Interactions ← this one acknowledges “contradictory data regarding the role of cranberry in kidney stone formation”

Where can I get some?

You can probably buy fresh, frozen, or dried cranberries from wherever you normally do your grocery shopping.

However, if you prefer to take it in supplement form, then here’s an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Aging Minds: Normal vs Abnormal Cognitive Decline

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Having a “senior moment” and having dementia are things that are quite distinct from one another; while we may very reasonably intend to fight every part of it, it’s good to know what’s “normal” as well as what is starting to look like progress into something more severe:

Know the differences

Cognitive abilities naturally decline with age, often beginning around 30 (yes, really—the first changes are mostly metabolic though, so this is far from set in stone). Commonly-noticed changes include:

- slower thinking

- difficulty multitasking

- reduced attention

- weaker memory.

Over time, these changes have what is believed to be a two-way association (as in, each causes/worsens the other) with changes in brain structure, especially reduced hippocampal and frontal lobe volume.

- Gradual cognitive changes are normal with age, whereas dementia involves a pathological decline affecting memory, problem-solving, and behavior.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) involves noticeable cognitive decline without disrupting daily life, while dementia affects everyday tasks like cooking or driving.

- Dementia causes significant impairments, including motor challenges like falls or tremors, and dementia-induced cognitive decline symptoms include forgetfulness, getting lost, personality changes, and planning difficulties, often worsening with stress or illness.

To best avoid these, consider: regular exercise, a nutritious diet, good quality sleep, social interaction, and mentally stimulating activities.

Also, often forgotten (in terms of its relevance at least): managing cardiovascular health is very important too. We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: what’s good for your heart is good for your brain (since the former feeds the latter with oxygen and nutrients, and also takes away detritus that will otherwise build up in the brain).

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Is It Dementia? Spot The Signs (Because None Of Us Are Immune) ← we go into more specific detail here

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Oat Milk vs Almond Milk – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing oat milk to almond milk, we picked the almond milk.

Why?

This one’s quite straightforward, and no, it’s not just our bias for almonds

Rather, almonds contain a lot more vitamins and minerals, all of which usually make it into the milk.

Oat milk is still a fine choice though, and has a very high soluble fiber content, which is great for your heart.

Just make sure you get versions without added sugar or other unpleasantries! You can always make your own at home, too.

You can read a bit more about the pros and cons of various plant milks here:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Hazelnuts vs Almonds – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing hazelnuts to almonds, we picked the almonds.

Why?

It’s closer than you might think! But we say almonds do come out on top.

In terms of macronutrients, almonds have notably more protein, while hazelnuts have notably more fat (healthy fats, though). Almonds are also higher in both carbs and fiber. Looking at Glycemic Index, hazelnuts’ GI is low and almonds’ GI is zero. We could call the macros category a tie, but ultimately if we need to prioritize any of these things, it’s protein and fiber, so we’ll call this a nominal win for almonds.

When it comes to vitamins, hazelnuts have more of vitamins B1, B5, B6, B9 C, and K. Meanwhile, almonds have more of vitamins B2, B3, E, and choline. So, a moderate win for hazelnuts.

In the category of minerals, almonds retake the lead with more calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while hazelnuts boast more copper and manganese. A clear win for almonds.

Adding up the categories, this makes for a marginal win for almonds. Of course, both of these nuts are very healthy (assuming you are not allergic), and best is to enjoy both if possible.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

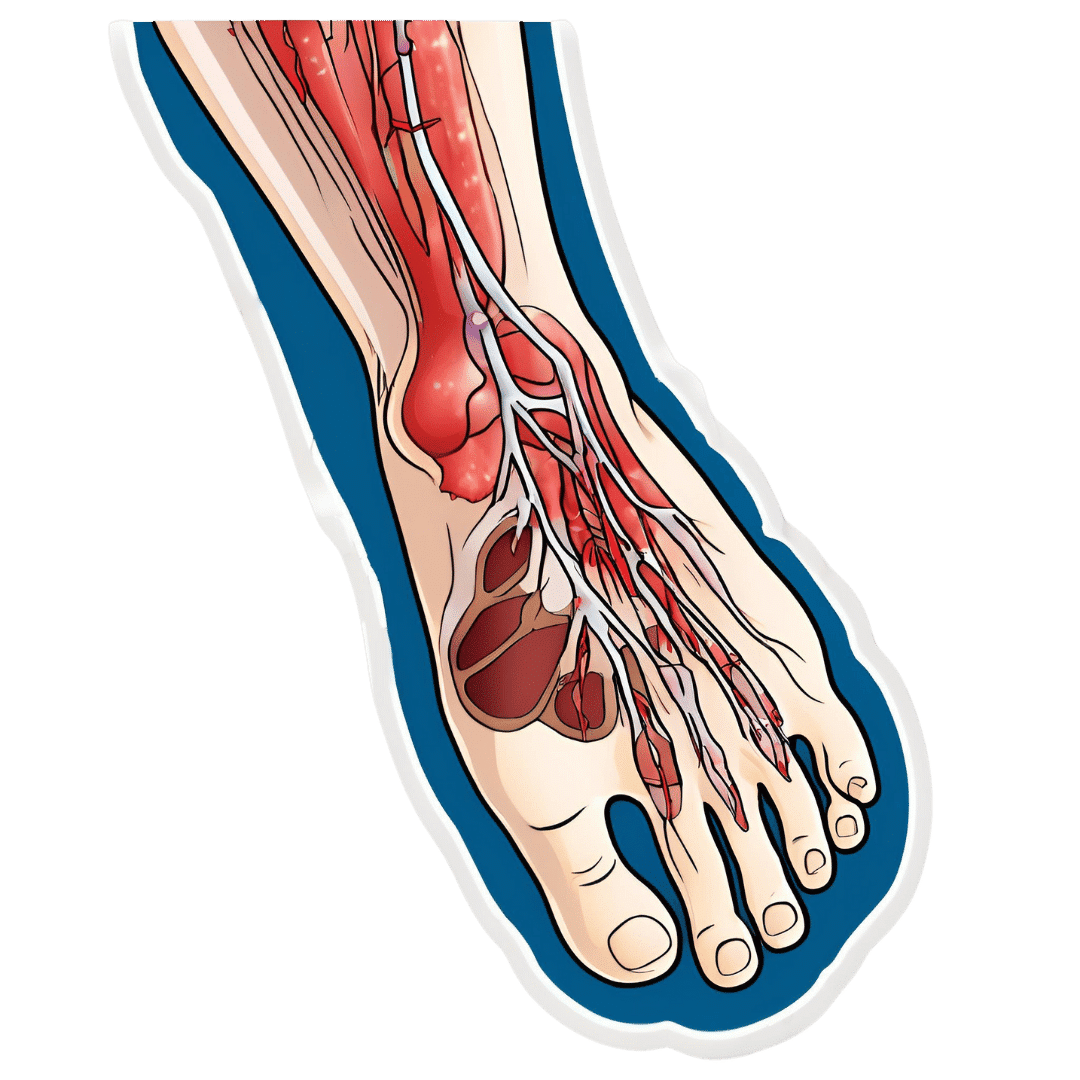

How To Stay A Step Ahead Of Peripheral Artery Disease

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Far less well-known than Coronary Artery Disease, it can still result in loss of life and limb (not in that order). Fortunately, there are ways to be on your guard:

What it is

Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) is the same thing as Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), just, in the periphery—which by definition means “outside of the heart and brain”, but in practice, it starts with the extremities. And of the extremities, it tends to start with the feet and legs, for the simple reason that if someone’s circulation is sluggish, then because of gravity, that’s where’s going to get blocked first.

In both CAD and PAD, the usual root cause is atherosclerosis, that is to say, the build-up of fatty material inside the arteries, usually commensurate to LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, especially in men (high LDL is still a predictor of cardiovascular disease in women though, just more modestly so, at least pre-menopause or in cases of treated menopause whereby HRT has returned hormones to pre-menopause levels).

See also: Demystifying Cholesterol

And for that about sex differences: His & Hers: The Hidden Complexities of Statins and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

Why it is

This one’s straightforward, as it’s the same things as any kind of cardiovascular disease: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, older age, obesity, smoking, drinking, diabetes, and genetic factors (so, a risk factor is: family history of heart disease).

However, while those are the main causes and/or risk factors, it absolutely can still strike other people, so it’s as well to be watch out for…

What to look out for

Many people first notice signs and symptoms that turn out to be PAD when they experience pain or numbness in the foot or feet, and/or a discoloration of the feet (especially toes), and slow wound healing.

At that stage, chances are you will need to go urgently to a specialist, and surgery is a likely necessity. With a little luck, it’ll be a minimally-invasive surgery to unblock an artery; failing that, an amputation will be in order.

At that stage, under 50% will be alive 5 years from diagnosis:

You probably want to avoid those. Good news is, you can, by catching it earlier!

What to look out for before that

The most common test for PAD is one you can do at home, but enlisting a nurse to do it for you will help ensure accurate readings. It’s called the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) test, and it involves comparing the blood pressure in your ankle with the blood pressure in your arm, and expressing them as a ratio.

Here’s how to do it (instructions and a video demonstration if you want it):

Do Try This At Home: ABI Test For Clogged Arteries

If you need a blood pressure monitor, by the way, here’s an example product on Amazon.

- A healthy ABI score is between 1.0 and 1.4; anything outside this range may indicate arterial problems.

- Low ABI scores (below 0.8) suggest plaque is likely obstructing blood flow

- High ABI scores (above 1.4) may indicate artery hardening

Do note also that yes, if you have plaque obstructing blood flow and hardened arteries, your scores may cancel out and give you a “healthy” score, despite your arteries being very much not healthy.

For this reason, this test can be used to raise the alarm, but not to give the “all clear”.

There are other tests that clinicians can do for you, but you can’t do at home unless you have an MRI machine, a CT scanner, an x-ray machine, a doppler-and-ultrasound machine, etc. We’ll not go into those in detail here, but ask your doctor about them if you’re concerned.

What to do about it

In the mid-to-late stages of the disease, the options are medication and surgery, respectively, but your doctor will advise about those in that eventuality.

In the early stages of the disease, the first-line recommend treatment is exercise, of which, especially walking:

Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment

Given that this more often happens when someone hasn’t been walking so much, it can be a walk-rest-walk approach at first (a treadmill on a low setting can be very useful for this):

See also: Exercise Comparison Head-to-Head: Treadmill vs Road

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Kombucha vs Kimchi – Which is Healthier

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kombucha to kimchi, we picked the kombucha.

Why?

While both are very respectable gut-healthy fermented products,

• the kombucha contains fermented tea, a little apple cider vinegar, and a little fiber

• the kimchi contains (after the vegetables) 810 mg sodium in that little tin, and despite the vegetables, no fiber.You may reasonably be surprised that they managed to take something that is made of mostly vegetables and ended up with no fiber without juicing it, but they did. Fermented vegetables are great for the healthy bacteria benefits (and are tasty too!), but the osmotic pressure due to the salt destroys the cell walls and thus the fiber.

Thus, we chose the kombucha that does the same job without delivering all that salt.

However! If you are comparing kombucha and kimchi out in the wilds of your local supermarket, do still check individual labels. It’s not uncommon, for example, for stores to sell pre-made kombucha that’s loaded with sugar.

About sugar and kombucha…

Sugar is required to make kombucha, to feed the yeast and helpful bacteria. However, there should be none of that sugar left (or only the tiniest trace amount) in the final product, because the yeast (and friends) consumed and metabolized it.

What some store brands do, however, is add in sugar afterwards, as they believe it improves the taste. This writer cannot imagine how, but that is their rationale in any case. Needless to say, it is not a healthy addition, and specifically, it’s bad for your gut, which (healthwise) is the whole point of drinking kombucha in the first place.

Want some? Here is an example product on Amazon, but feel free to shop around as there are many flavors available!

Read more about gut health: Gut Health 101

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Outlive – by Dr. Peter Attia

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We know, we know; this diet, that exercise, don’t smoke or drink, get decent sleep”—a lot of books don’t go beyond this level of advice!

What Dr. Attia offers is a multi-vector approach that covers the above and a lot more.

Themes of the book include:

- The above-mentioned things, of course

- Rethinking medicine for the age of chronic disease

- The pros and cons of…

- caloric restriction

- dietary restriction

- intermittent fasting

- Pre-emptive interventions for…

- specific common cause-of-death conditions

- specific common age-related degenerative conditions

- The oft-forgotten extra pillar of longevity: mental health

The last one in the list there is covered mostly in the last chapter of the book, but it’s there as a matter of importance, not as an afterthought. As Dr. Attia puts it, not only are you less likely to take care of your physical health if you are (for example) depressed, but also… “Longevity is meaningless if your life sucks!”

So, it’s important to do things that promote and maintain good physical and mental health.

Bottom line: if you’re interested in happy, healthy, longevity, this is a book for you.

Click here to check out Dr. Attia’s “Outlive” on Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: