Behavioral Activation Against Depression & Anxiety

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Behavioral Activation Against Depression & Anxiety

Psychologists do love making fancy new names for things.

You thought you were merely “eating your breakfast”, but now it’s “Happiness-Oriented Basic Behavioral Intervention Therapy (HOBBIT)” or something.

This one’s quite simple, so we’ll keep it short for today, but it is one more tool for your toolbox:

What is Behavioral Activation?

Behavioral Activation is about improving our mood (something we can’t directly choose) by changing our behavior (something we usually can directly choose).

An oversimplified (and insufficient, as we will explain, but we’ll use this one to get us started) example would be “whistle a happy tune and you will be happy”.

Behavioral Activation is not a silver bullet

Or if it is, then it’s the kind you have to keep shooting, because one shot is not enough. However, this becomes easier than you might think, because Behavioral Activation works by…

Creating a Positive Feedback Loop

A lot of internal problems in depression and anxiety are created by the fact that necessary and otherwise desirable activities are being written off by the brain as:

- Pointless (depression)

- Dangerous (anxiety)

The inaction that results from these aversions creates a negative feedback loop as one’s life gradually declines (as does one’s energy, and interest in life), or as the outside world seems more and more unwelcoming/scary.

Instead, Behavioral Activation plans activities (usually with the help of a therapist, as depressed/anxious people are not the most inclined to plan activities) that will be:

- attainable

- rewarding

The first part is important, because the maximum of what is “attainable” to a depressed/anxious person can often be quite a small thing. So, small goals are ideal at first.

The second part is important, because there needs to be some way of jump-starting a healthier dopamine cycle. It also has to feel rewarding during/after doing it, not next year, so short term plans are ideal at first.

So, what behavior should we do?

That depends on you. Behavioral Activation calls for keeping track of our activities (bullet-journaling is fine, and there are apps* that can help you, too) and corresponding moods.

*This writer uses the pragmatic Daylio for its nice statistical analyses of bullet-journaling data-points, and the very cute Finch for more keyword-oriented insights and suggestions. Whatever works for you, works for you, though! It could even be paper and pen.

Sometimes the very thought of an activity fills us with dread, but the actual execution of it brings us relief. Bullet-journaling can track that sort of thing, and inform decisions about “what we should do” going forwards.

Want a ready-made brainstorm to jump-start your creativity?

Here’s list of activities suggested by TherapistAid (a resource hub for therapists)

Want to know more?

You might like:

- How To Use Behavioral Activation (guide for end users)

- Treatment Guide: Behavioral Activation (guide for clinicians)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Apple vs Apricot – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apple to apricot, we picked the apricot.

Why?

In terms of macros, there’s not too much between them; apples are higher in carbs and only a little higher in fiber, which disparity makes for a slightly higher glycemic index, but it’s not a big difference and they are both low GI foods.

Micronutrients, however, set these two fruits apart:

In the category of vitamins, apple is a tiny bit higher in choline, while apricots are higher in vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, E, and K—in most cases, by quite large margins, too. All in all, a clear and easy win for apricots.

When it comes to minerals, apples are not higher in any minerals, while apricots are higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. There’s simply no contest here.

In short, if an apple a day keeps the doctor away, then an apricot will give the doctor a nice weekend break somewhere.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Ear Candling: Is It Safe & Does It Work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Does This Practice Really Hold A Candle To Evidence-Based Medicine?

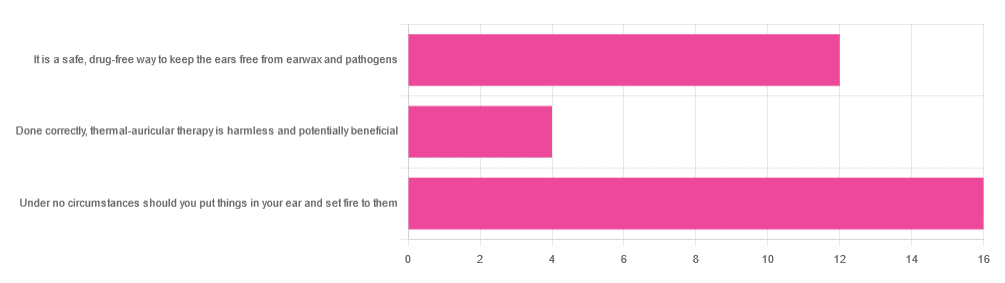

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion of ear candling, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of responses:

- Exactly 50% said “Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them”

- About 38% said “It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens”

- About 13% said “Done correctly, thermal-auricular therapy is harmless and potentially beneficial”

This means that if we add the two positive-to-candling answers together, it’s a perfect 50:50 split between “do it” and “don’t do it”.

(Yes, 38%+13%=51%, but that’s because we round to the nearest integer in these reports, and more precisely it was 37.5% and 12.5%)

So, with the vote split, what does the science say?

First, a quick bit of background: nobody seems keen to admit to having invented this. One of the major manufacturers of ear candles refers to them as “Hopi” candles, which the actual Hopi tribe has spent a long time asking them not to do, as it is not and never has been used by the Hopi people. Other proposed origins offered by advocates of ear candling include Traditional Chinese Medicine (not used), Ancient Egypt (no evidence of such whatsoever), and Atlantis:

Quackwatch | Why Ear Candling Is Not A Good Idea

It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens: True or False?

False! In a lot of cases of alternative therapy claims, there’s an absence of evidence that doesn’t necessarily disprove the treatment. In this case, however, it’s not even an open matter; its claims have been actively disproven by experimentation:

- It doesn’t remove earwax; on the contrary, experimentation “showed no removal of cerumen from the external auditory canal. Candle wax was actually deposited in some“

- It doesn’t remove pathogens, and the proposed mechanism of action for removing pathogens, that of the “chimney effect”: the idea that the burning candle creates a vacuum that draws wax out of the ear along with debris and bacteria, simply does not work; on the contrary, “Tympanometric measurements in an ear canal model demonstrated that ear candles do not produce negative pressure”.

- It isn’t safe; on the contrary, “Ear candles have no benefit in the management of cerumen and may result in serious injury”

In a medium-sized survey (n=122), the following injuries were reported:

- 13 x burns

- 7 x occlusion of the ear canal

- 6 x temporary hearing loss

- 3 x otitis externa (this also called “swimmer’s ear”, and is an inflammation of the ear, accompanied by pain and swelling)

- 1 x tympanic membrane perforation

Indeed, authors of one paper concluded:

❝Ear candling appears to be popular and is heavily advertised with claims that could seem scientific to lay people. However, its claimed mechanism of action has not been verified, no positive clinical effect has been reliably recorded, and it is associated with considerable risk.

No evidence suggests that ear candling is an effective treatment for any condition. On this basis, we believe it can do more harm than good and we recommend that GPs discourage its use❞

Source: Canadian Family Physician | Ear Candling

Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them: True or False?

True! It’s generally considered good advice to not put objects in general in your ears.

Inserting flaming objects is a definite no-no. Please leave that for the Cirque du Soleil.

You may be thinking, “but I have done this and suffered no ill effects”, which seems reasonable, but is an example of survivorship bias in action—it doesn’t make the thing in question any safer, it just means you were one of the one of the ones who got away unscathed.

If you’re wondering what to do instead… Ear oils can help with the removal of earwax (if you don’t want to go get it sucked out at a clinic—the industry standard is to use a suction device, which actually does what ear candles claim to do). For information on safely getting rid of earwax, see our previous article:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Superfood Energy Balls

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

They are healthy, they are tasty, they are convenient! Make some of these and when you need an energizing treat at silly o’clock when you don’t have time to prepare something, here they are, full of antioxidants, vitamins and minerals, good for blood sugars too, and ready to go:

You will need

- 1 cup pitted dates

- 1 cup raw mixed nuts

- ¼ cup goji berries

- 1 tbsp cocoa powder

- 1 tsp chili flakes

Naturally, you can adjust the spice level if you like! But this is a good starter recipe.

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Blend all the ingredients in a good processor to make a dough

2) Roll the dough into 1″ balls; you should have enough dough for about 16 balls. If you want them to be pretty, you can roll them in some spare dry ingredients (e.g. chopped nuts, goji berries, chili flakes, seeds of some kind, whatever you have in your kitchen that fits the bill).

3) Refrigerate for at least 1–2 hours, and serve! They can also be kept in the fridge for at least a good while—couldn’t tell you how long for sure though, because honestly, they’ve never stayed that long in the fridge without being eaten.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Dates vs Figs – Which is Healthier?

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

- The Sugary Food That Lowers Blood Sugars

- Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

- Capsaicin’s Hot Benefits

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Can You Repair Your Own Teeth At Home?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝I liked your article on tooth remineralization, I saw a “home tooth repair kit”, and wondered if it is as good as what dentists do, or at least will do the job well enough to save a dentist visit?❞

Firstly, for any wondering about the tooth remineralization, here you go:

Tooth Remineralization: How To Heal Your Teeth Naturally

Now, to answer your question, we presume you are talking about something like this kit available on Amazon. In which case, some things to bear in mind:

- This kind of thing is generally intended as a stop-gap measure until you see a dentist, because you cracked your tooth or lost a filling or something today, and will see the dentist next week, say.

- This kind of thing is not what Dr. Michelle Jorgensen was talking about in another video* that we wrote about; rather, it is using a polymer filler to rebuild what is missing. The key difference is: this is using plastic, which is not what your teeth are made of, so it will never “take” as part of the tooth, as some biomimetic dentistry options can do.

- Yes, this does also mean you are putting microplastics (because the powder is usually micronized polymer beads with zinc oxide, to which you add a liquid to create a paste that will set) in your mouth and quite possibly right next to an open blood supply depending on what’s damaged and whether capillaries were reaching it.

- Because of the different material and application method, the adhesion is nothing like professional fillings (be they metal or resin), and thus the chances of it coming out again or so high that it’s more a question of when, rather than if.

- If you have damage under there (as we presume you do in any scenario where you are using this), then if it’s not professionally cleaned before the filling goes in, then it can get infected, and (less dramatically, but still importantly) any extant decay can also get worse. We say “professionally”, because you will not be able to do an adequate job with your toothbrush, floss, etc at home, and even if you got dentist’s tools (which you can buy, by the way, but we don’t recommend), you will no more be able to do the same quality job as a dentist who has done that many times a day every day for the past 20 years, as buying expensive paintbrushes would make you able to restore a Renaissance painting without messing it up.

*See: Dangers Of Root Canals And Crowns, & What To Do Instead ← what she recommends instead is biomimetic dentistry, which is also more prosaically called “conservative restorative dentistry”, i.e. it tries to conserve as much as possible, replace lost material on a like-for-like basis, and generally end up with a result that’s as close to natural as possible.

In other words, the short answer to your question is “no, sorry, it isn’t and it won’t”

However! A just like it’s good to have a first aid kit in the house even if it won’t do the same job as an ambulance crew, it can be good to have a tooth repair kit (essentially, a tooth first-aid kit) in the house, precisely to use it just as a stop-gap measure in the event that you one day crack a tooth or lose a filling or such, and don’t want to leave it open to all things in the meantime.

(The results of this sort of kit are so not long-term in nature that it will be quick and easy for your dentist to remove it to do their own job once you get there)

If in doubt, always see your dentist as soon as possible, as many things are a lot less work to treat now, than to treat later. Just, make sure to advocate for yourself and what you actually want/need, and don’t let them upsell you on something you didn’t come in for while you’re sitting in their chair—that’s a conversation to be had in advance with a clear head and no pressure (and nobody’s hands in your mouth)!

See also: Dentists Are Pulling ‘Healthy’ and Treatable Teeth To Profit From Implants, Experts Warn

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Intermittent Fasting for Women Over 50 – by Emma Sanchez

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Intermittent fasting is promoted as a very healthful (evidence-based!) way to trim the fat and slow aging, along with other health benefits. But, physiologically and especially metabolically, the average woman is quite different from the average man! And most resources are aimed at men. So, what’s the difference?

Emma Sanchez gives an overview not just of intermittent fasting, but also, how it goes with specifically female physiology. From hormonal cycles, to different body composition and fat distribution, to how we simply retain energy better—which can be a mixed blessing!

We’re given advice about how to optimize all those things and more.

She also covers issues that many writers on the topic of intermittent fasting will tend to shy away from, such as:

- mood swings

- risk of eating disorder

- impact on cognitive thinking

…and she does this evenly and fairly, making the case for intermittent fasting while acknowledging potential pitfalls that need to be recognized in order to be managed.

Lastly, the “over 50” thing. This is covered in detail quite late in the book, but there are a lot of changes that occur (beyond the obvious!), and once again, Sanchez has tips and tricks for holding back the clock where possible, and working with it rather than against it, when appropriate.

All in all, a great book for any woman over 50, or really also for women under 50, especially if that particular milestone is on the horizon.

Get your copy of Intermittent Fasting for Women over 50 from Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Tips For Avoiding/Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Avoiding/Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis

Arthritis is the umbrella term for a cluster of joint diseases involving inflammation of the joints, hence “arthr-” (joint) “-itis” (suffix used to denote inflammation). These are mostly, but not all, autoimmune diseases, in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks our own joints.

Inflammatory vs Non-Inflammatory Arthritis

Arthritis is broadly divided into inflammatory arthritis and non-inflammatory arthritis.

You may be wondering: how does one get non-inflammatory inflammation of the joints?

The answer is, in “non-inflammatory” arthritis, such as osteoarthritis, the damage comes first (by general wear-and-tear) and inflammation generally follows as part of the symptoms, rather than the cause. So the name can be a little confusing. In the case of osteo- and other “non-inflammatory” forms of arthritis, you definitely still want to keep your inflammation at bay as best you can, but it’s not as absolutely critical a deal as it is for “inflammatory” forms of arthritis.

We’ll tackle the beast that is osteoarthritis another day, however.

Today we’re going to focus on…

Rheumatoid Arthritis

This is the most common of the autoimmune forms of arthritis. Some quick facts:

- It affects a little under 1% of the global population, but the older we get, the more likely it becomes

- Early onset of rheumatoid arthritis is most likely to show up around the age of 50 (but it can show up at any age)

- However, incidence (not onset) of rheumatoid arthritis peaks in the 70s age bracket

- It is 2–4 times more common in women than in men

- Approximately one third of people stop work within two years of its onset, and this increases thereafter.

Well, that sounds gloomy.

Indeed it’s not fun. There’s a lot of stiffness and aching of joints (often with swelling too), loss of joint function can be common, and then there are knock-on effects like fatigue, weakness, and loss of appetite.

Beyond that it’s an autoimmune disorder, its cause is not known, and there is no known cure.

Is there any good news?

If you don’t have rheumatoid arthritis at the present time, you can reduce your risk factors in several ways:

- Having an anti-inflammatory diet. Get plenty of fiber, greens, and berries. Fatty fish is great too, as are oily nuts. On the other side of things, high consumption of salt, sugar, alcohol, and red meat are associated with a greater risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis.

- Not smoking. Smoking is bad for pretty much everything, including your chances of developing rheumatoid arthritis.

- Not being obese. This one may be more a matter of correlation than causation, because of the dietary factors (if one eats an anti-inflammatory diet, obesity is less likely), but the association is there.

There are other risk factors that are harder to control, such as genetics, age, sex, and having a mother who smoked.

See: Genetic and environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis

What if I already have rheumatoid arthritis?

If you already have rheumatoid arthritis, it becomes a matter of symptom management.

First, reduce inflammation any (reasonable) way you can. We did a main feature on this before, so we’ll just drop that again here:

Next, consider the available medications. Your doctor may or may not have discussed all of the options with you, so be aware that there are more things available than just pain relief. To talk about them all would require a whole main feature, so instead, here’s a really well-compiled list, along with explanations about each of them, up to date as of this year:

Rheumatoid Arthritis Medication List (And What They Do, And How)

Finally, consider other lifestyle adjustments to manage your symptoms. These include:

- Exercise—gently, though! You do not want to provoke a flare-up, but you do want to maintain your mobility as best you can. There’s a use-it-or-lose-it factor here. Swimming and yoga are great options, as is tai chi. You may want to avoid exercises that involve repetitive impacts to your joints, like running.

- Rest—while keeping mobility going. Get good sleep at night (this is important), but don’t make your bed your new home, or your mobility will quickly deteriorate.

- Hot & cold—both can help, and alternating them can reduce inflammation and stiffness by improving your body’s ability to respond appropriately to these stimuli rather than getting stuck in an inappropriate-response state of inflammation.

- Mobility aids—if it helps, it helps. Maybe you only need something during a flare-up, but when that’s the case, you want to be as gentle on your body as possible while keeping moving, so if crutches, handrails etc help, then by all means get them and use them.

- Go easy on the use of braces, splints, etc—these can offer short-term relief, but at a long term cost of loss of mobility. Only you can decide where to draw the line when it comes to that trade-off.

You can also check out our previous article:

Managing Chronic Pain (Realistically!)

Take good care of yourself!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: