Can We Side-Step Age-Related Alienation?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When The World Moves Without Us…

We’ve written before about how reduced social engagement can strike people of all ages, and what can be done about it:

How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

…but today we’re going to talk more about a specific aspect of it, namely, the alienation that can come with old age—and other life transitions too, but getting older is something that (unless accident or incident befall us first) all of us will definitely do.

What’s the difference?

Loneliness is a status, alienation is more of a process. It can be the alienation in the sense of an implicit “you don’t belong here” message from the world that’s geared around the average person and thus alienates those who are not that (a lack of accessibility to people with disabilities can be an important and very active example of this), and it can also be an alienation from what we’ve previously considered our “niche” in the world—the loss of purpose many people feel upon retirement fits this bill. It can even be a more generalized alienation from our younger selves; it’s easy to have a self-image that doesn’t match one’s current reality, for instance.

Read more: Estranged by Time: Alienation in the Aging Process

So, how to “un-alienate”?

To “un-alienate”, that is to say, to integrate/reintegrate, can be hard. Some things may even be outright impossible, but most will not be!

Consider how, for example, former athletes become coaches—or for that matter, how former party-goers might become party-hosts (even if the kind of “party” might change with time, give or take the pace at which we like to live our lives).

What’s important is that we take what matters the most to us, and examine how we can realistically still engage with that thing.

This is different from trying to hold on grimly to something that’s no longer our speed.

Letting go of the only thing we’ve known will always be scary; sometimes it’s for the best, and sometimes what we really need is just more of a pivot, like the examples above. The crux lies in knowing which:

- Is our relationship with the thing (whatever it may be) still working for us, or is it just bringing strife now?

- If it’s not working for us, is it because of a specific aspect that could be side-stepped while keeping the rest?

- If we’re going to drop that thing entirely (or be dropped by it, which, while cruel, also happens in life), then where are we going to land?

This latter is one where foresight is a gift, because if we bury our heads in the sand we’re going to land wherever we’re dropped, whereas if we acknowledge the process, we can make a strategic move and land on our feet.

Here’s a good pop-science article about this—it’s aimed at people around retirement age, but honestly the advice is relevant for people of all ages, and facing all manner of life transitions, e.g. career transitions (of which retirement is of course the career transition to end all career transitions), relationship transitions (including B/B/B/B: births, betrothals/break-ups, and bereavements) health transitions (usually: life-changing illnesses and/or disabilities—which again, happens to most of us if something doesn’t get us first), etc. So with all that in mind, this becomes more of a “how to reassess your life at those times when it needs reassessing”:

How to Reassess Your Life in Retirement

But that doesn’t mean that letting go is always necessary

Sometimes, the opposite! Sometimes, the age-old advice to “lean in” really is all the situation calls for, which means:

- Be ready to say “yes” to things, and if nobody’s asking, be ready to “hey, do you wanna…?” and take a “build it and they will come” approach. This includes with people of different ages, too! Intergenerational friendships can be very rewarding for all concerned, if done right. Communities that span age-ranges can be great for this—they might be about special interests (this writer has friends ranging through four generations from playing chess, for instance), they could be religious communities if we be religious, LGBT groups if that fits for us, even mutual support groups such as for specific disabilities or chronic illness if we have such—notice how the very things that might isolate us can also bring us together!

- Be open-minded to new experiences; it’s easy to get stuck in a rut of “I’ve never done that” and mistake that self-assessment for an uncritical assumption of “I’m not the kind of person who does that”. Sometimes, you really won’t be! But at least think about it and entertain the possibility, before dismissing it out of hand. And, here’s a life tip: it can be really good to (within the realms of safety, and one’s personal moral principles, of course) take an approach of “try anything once”. Even if we’re almost certain we won’t like it, and even if we then turn out to indeed not like it, it can be a refreshing experience—and now we can say “Yep, tried that, not doing that again” from a position of informed knowledge. That’s the only way we get to look back on a richly lived life of broad experiences, after all, and it is never too late for such.

- Be comfortable prioritizing quality over quantity. This goes for friends, it goes for activities, it goes for experiences. The topic of “what’s the best number of friends to have?” has been a matter of discussion since at least ancient Greek times (Plato and Aristotle examined this extensively), but whatever number we might arrive at, it’s clear that quality is the critical factor, and quantity after that is just a matter of optimizing.

In short: make sure you’re investing—in your relationships, in your areas of interest, in your community (whatever that may mean for you personally), and most of all, and never forget this: in yourself.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Beat Osteoporosis with Exercise – by Dr. Karl Knopf

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are a lot of books about beating osteoporosis, and yet when it comes to osteoporosis exercises, it took us some work to find a good one. But, this one’s it!

A lot of books give general principles and a few sample exercises. This one, in contrast, gives:

- An overview of osteopenia and osteoporosis, first

- A brief overview of non-exercise osteoporosis considerations

- Principles for exercising a) to reduce one’s risk of osteoporosis b) if one has osteoporosis

- Clear explanations of about 150 exercises that fit both categories

This last item’s important, because a lot of popular advice is exercises that are only good for one or the other (given that a lot of things that strengthen a healthy person’s bones can break the bones of someone with osteoporosis), so having 150 exercises that are safe and effective in both cases, is a real boon.

That doesn’t mean you have to do all 150! If you want to, great. But even just picking and choosing and putting together a little program is good.

Bottom line: if you’d like a comprehensive guide to exercise to keep you strong in the face of osteoporosis, this is a great one.

Click here to check out Beat Osteoporosis With Exercise, and stay strong!

Share This Post

-

Healthy Relationship, Healthy Life

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Only One Kind Of Relationship Promotes Longevity This Much!

One of the well-established keys of a long healthy life is being in a fulfilling relationship. That’s not to say that one can’t be single and happy and fulfilled—one totally can. But statistically, those who live longest, do so in happy, fulfilling, committed relationships.

Note: happy, fulfilling, committed relationships. Less than that won’t do. Your insurance company might care about your marital status for its own sake, but your actual health doesn’t—it’s about the emotional safety and security that a good, healthy, happy, fulfilling relationship offers.

How to keep the “love coals” warm

When “new relationship energy” subsides and we’ve made our way hand-in-hand through the “honeymoon period”, what next? For many, a life of routine. And that’s not intrinsically bad—routine itself can be comforting! But for love to work, according to relational psychologists, it also needs something a little more.

What things? Let’s break it down…

Bids for connection—and responsiveness to same

There’s an oft-quoted story about a person who knew their marriage was over when their spouse wouldn’t come look at their tomatoes. That may seem overblown, but…

When we care about someone, we want to share our life with them. Not just in the sense of cohabitation and taxes, but in the sense of:

- Little moments of joy

- Things we learned

- Things we saw

- Things we did

…and there’s someone we’re first to go to share these things with. And when we do, that’s a “bid for connection”. It’s important that we:

- Make bids for connection frequently

- Respond appropriately to our partner’s bids for connection

Of course, we cannot always give everything our full attention. But whenever we can, we should show as much genuine interest as we can.

Keep asking the important questions

Not just “what shall we have for dinner?”, but:

- “What’s a life dream that you have at the moment?”

- “What are the most important things in life?”

- “What would you regret not doing, if you never got the chance?”

…and so forth. Even after many years with a partner, the answers can sometimes surprise us. Not because we don’t know our partners, but because the answers can change with time, and sometimes we can even surprise ourselves, if it’s a question we haven’t considered for a while.

It’s good to learn and grow like this together—and to keep doing so!

Express gratitude/appreciation

For the little things as well as the big:

- Thank you for staying by my side during life’s storms

- Thank you for bringing me a coffee

- Thank you for taking on these responsibilities with me

- I really appreciate your DIY skills

- I really appreciate your understanding nature

On which note…

Compliment, often and sincerely

Most importantly, compliment things intrinsic to their character, not just peripheral attributes like appearance, and also not just what they do for you.

- You’re such a patient person; I really admire that

- I really hit the jackpot to get someone I can trust so completely as you

- You are the kindest and sweetest soul I have ever encountered in life

- I love that you have such a blend of strength and compassion

- Your unwavering dedication to your personal values makes me so proud

…whatever goes for your partner and how you see them and what you love about them!

Express your needs, and ask about theirs

We’re none of us mind-readers, and it’s easy to languish in “if they really cared, I wouldn’t have to ask”, or conversely, “if they wanted something, they would surely say so”.

Communicate. Effectively. Life is too short to waste in miscommunication and unsaid things!

We covered much more detailed how-tos of this in a previous issue, but good double-whammy of top tier communication is:

- “I need…” / “Please will you…”

- “What do you need?” / “How can I help?”

Touch. Often.

It takes about 20 seconds of sustained contact for oxytocin to take effect, so remember that when you hug your partner, hold hands when walking, or cuddle up the sofa.

Have regular date nights

It doesn’t have to be fancy. A date night can be cooking together, it can be watching a movie together at home. It can be having a scheduled time to each bring a “big question” or five, from what we talked about above!

Most importantly: it’s a planned shared experience where the intent is to enjoy each other’s romantic company, and have a focus on each other. Having a regularly recurring date night, be it the last day of each month, or every second Saturday, or every Friday night, whatever your schedules allow, makes such a big difference to feel you are indeed “dating” and in the full flushes of love—not merely cohabiting pleasantly.

Want ideas?

Check out these:

Share This Post

-

Beetroot vs Tomato – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing beetroot to tomato, we picked the beetroot.

Why?

Both are great! But we say beetroot comes out on top:

In terms of macros, beetroot has more protein, carbs, and fiber, making it the more nutritionally dense option. It has a slightly higher glycemic index, but also has specific phytochemicals that lower blood sugars and increase insulin sensitivity, more than cancelling that out. So, a clear win for beetroot in this regard.

In the category of vitamins, beetroot has more of vitamins B2, B5, B7, and B9, while tomato has more of vitamins A, C, E, and K. We’d call that a 4:4 tie, but tomato’s margins of difference are greater, so we say tomato wins this round.

When it comes to minerals, beetroot has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while tomatoes are not higher in any mineral. An easy win for beetroot here.

Looking at polyphenols and other remaining phytochemicals, beetroot has most, and especially its betalain content goes a long way. Tomatoes, meanwhile, have a famously high lycopene content (a highly beneficial carotenoid). All in all, it could swing either way based on subjective factors, so we’re saying it’s a tie this time.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for beetroot, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

- Beetroot For More Than Just Your Blood Pressure

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Bitter Truth About Coffee (or is it?)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Bitter Truth About Coffee (or is it?)

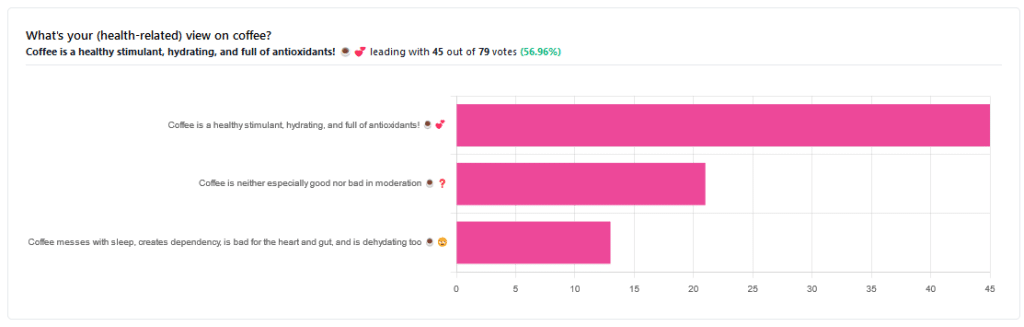

Yesterday, we asked you for your (health-related) views on coffee. The results were clear: if we assume the responses to be representative, we’re a large group of coffee-enthusiasts!

One subscriber who voted for “Coffee is a healthy stimulant, hydrating, and full of antioxidants” wrote:

❝Not so sure about how hydrating it is! Like most food and drink, moderation is key. More than 2 or 3 cups make me buzz! Just too much.❞

And that fine point brings us to our first potential myth:

Coffee is dehydrating: True or False?

False. With caveats…

Coffee, in whatever form we drink it, is wet. This may not come as a startling revelation, but it’s an important starting point. It’s mostly water. Water itself is not dehydrating.

Caffeine, however, is a diuretic—meaning you will tend to pee more. It achieves its diuretic effect by increasing blood flow to your kidneys, which prompts them to release more water through urination.

See: Effect of caffeine on bladder function in patients with overactive bladder symptoms

How much caffeine is required to have a diuretic effect? About 4.5 mg/kg.

What this means in practical terms: if you weigh 70kg (a little over 150lbs), 4.5×70 gives us 315.

315mg is about how much caffeine might be in six shots of espresso. We say “might” because while dosage calculations are an exact science, the actual amount in your shot of espresso can vary depending on many factors, including:

- The kind of coffee bean

- How and when it was roasted

- How and when it was ground

- The water used to make the espresso

- The pressure and temperature of the water

…and that’s all without looking at the most obvious factor: “is the coffee decaffeinated?”

If it doesn’t contain caffeine, it’s not diuretic. Decaffeinated coffee does usually contain tiny amounts of caffeine still, but with nearer 3mg than 300mg, it’s orders of magnitude away from having a diuretic effect.

If it does contain caffeine, then the next question becomes: “and how much water?”

For example, an Americano (espresso, with hot water added to make it a long drink) will be more hydrating than a ristretto (espresso, stopped halfway through pushing, meaning it is shorter and stronger than a normal espresso).

A subscriber who voted for “Coffee messes with sleep, creates dependency, is bad for the heart and gut, and is dehydrating too” wrote:

❝Coffee causes tachycardia for me so staying away is best. People with colon cancer are urged to stay away from coffee completely.❞

These are great points! It brings us to our next potential myth:

Coffee is bad for the heart: True or False?

False… For most people.

Some people, like our subscriber above, have an adverse reaction to caffeine, such as tachycardia. An important reason (beyond basic decency) for anyone providing coffee to honor requests for decaff.

For most people, caffeine is “heart neutral”. It doesn’t provide direct benefits or cause direct harm, provided it is enjoyed in moderation.

See also: Can you overdose on caffeine?

Some quick extra notes…

That’s all we have time for in myth-busting, but it’s worth noting before we close that coffee has a lot of health benefits; we didn’t cover them today because they’re not contentious, but they are interesting nevertheless:

- Coffee is the world’s biggest source of antioxidants

- 65% reduced risk of Alzheimer’s for coffee-drinkers

- 67% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes for coffee-drinkers

- 43% reduced risk of liver cancer for coffee-drinkers

- 53% reduced suicide risk for coffee-drinkers

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

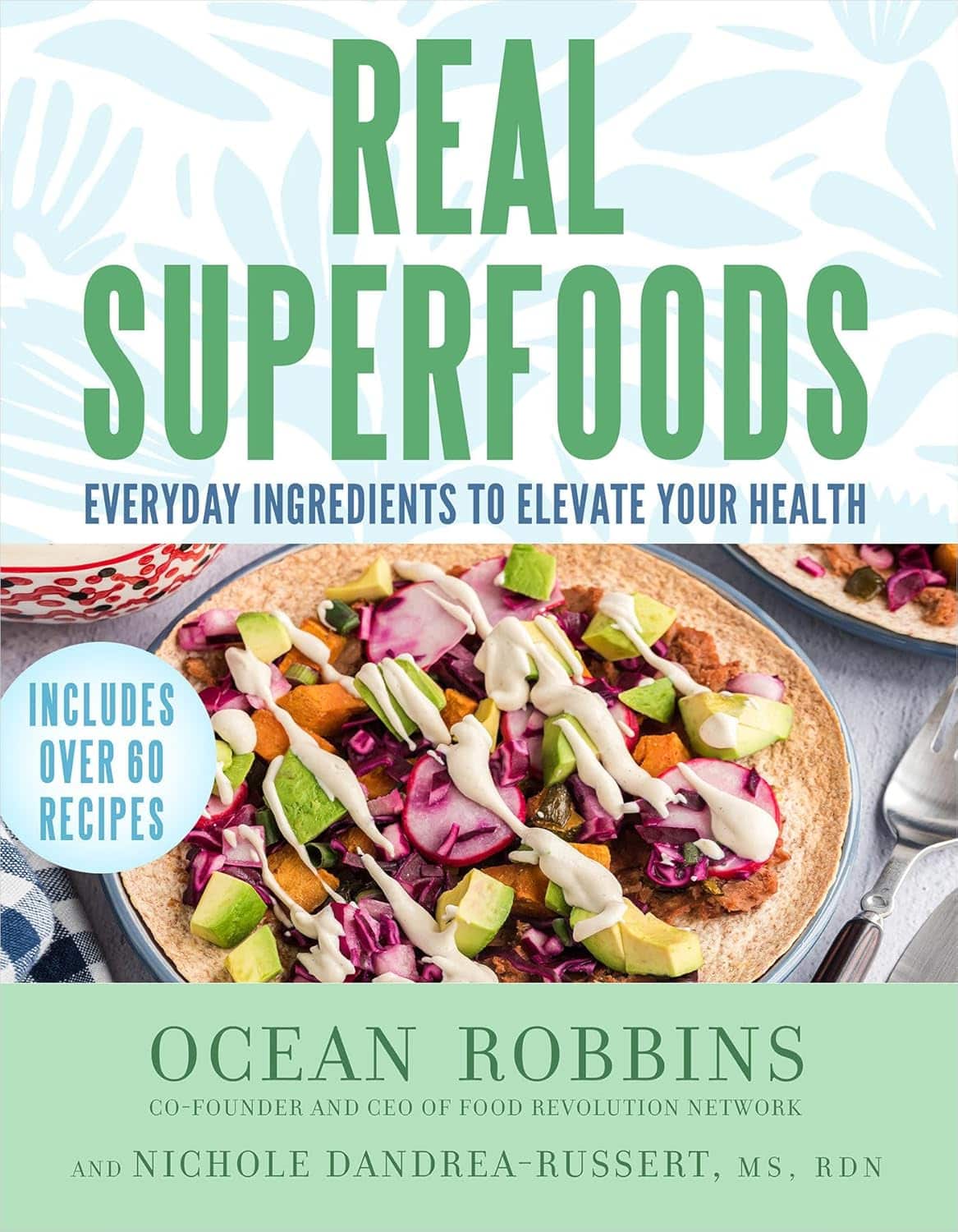

Real Superfoods – by Ocean Robbins & Nichole Dandrea-Russert

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Of the two authors, the former is a professional public speaker, and the latter is a professional dietician. As a result, we get a book that is polished and well-presented, while actually having a core of good solid science (backed up with plenty of references).

The book is divided into two parts; the first part has 9 chapters pertaining to 9 categories of superfood (with more details about top-tier examples of each, within), and the second part has 143 pages of recipes.

And yes, as usual, a couple of the recipes are “granola” and “smoothie”, but when are they not? Most of the recipes are worthwhile, though, with a lot of good dishes that should please most people.

Bottom line: this is half pop-science presentation of superfoods, and half cookbook featuring those ingredients. Definitely a good way to increase your consumption of superfoods, and get the most out of your diet.

Click here to check out Real Superfoods, and power up your health!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Kiwi Fruit vs Pineapple – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kiwi fruit to pineapple, we picked the kiwi.

Why?

In terms of macros, they’re mostly quite comparable, being fruits made of mostly water, and a similar carb count (slightly different proportions of sugar types, but nothing that throws out the end result, and the GI is low for both). Technically kiwi has twice the protein, but they are fruits and “twice the protein” means “0.5g difference per 100g”. Aside from that, and more meaningfully, kiwi also has twice the fiber.

When it comes to vitamins, kiwi has more of vitamins A, B9, C, E, K, and choline, while pineapple has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, and B6. This would be a marginal (6:5) win for kiwi, but kiwi’s margins of difference are greater per vitamin, including 72x more vitamin E (with a cupful giving 29% of the RDA, vs a cupful of pineapple giving 0.4% of the RDA) and 57x more vitamin K (with a cupful giving a day’s RDA, vs a cupful of pineapple giving a little under 2% of the RDA). So, this is a fair win for kiwi.

In the category of minerals, things are clear: kiwi has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while pineapple has more manganese. An overwhelming win for kiwi.

Looking at their respective anti-inflammatory powers, pineapple has its special bromelain enzymes, which is a point in its favour, but when it comes to actual polyphenols, the two fruits are quite balanced, with kiwi’s flavonoids vs pineapple’s lignans.

Adding up the sections, it’s a clear win for kiwi—but pineapple is a very respectable fruit too (especially because of its bromelain content), so do enjoy both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: