Eyes for Alzheimer’s Diagnosis: New?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Time!

This is the bit whereby each week, we respond to subscriber questions/requests/etc

Have something you’d like to ask us, or ask us to look into? Hit reply to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom, and a Real Human™ will be glad to read it!

Q: As I am a retired nurse, I am always interested in new medical technology and new ways of diagnosing. I have recently heard of using the eyes to diagnose Alzheimer’s. When I did some research I didn’t find too much. I am thinking the information may be too new or I wasn’t on the right sites.

(this is in response to last week’s piece on lutein, eyes, and brain health)

We’d readily bet that the diagnostic criteria has to do with recording low levels of lutein in the eye (discernible by a visual examination of macular pigment optical density), and relying on the correlation between this and incidence of Alzheimer’s, but we’ve not seen it as a hard diagnostic tool as yet either—we’ll do some digging and let you know what we find! In the meantime, we note that the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease (which may be of interest to you, if you’re not already subscribed) is onto this:

See also:

- Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease (mixture of free and paid content)

- Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports (open access—all content is free)

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Are Brain Chips Safe?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ready For Cyborgization?

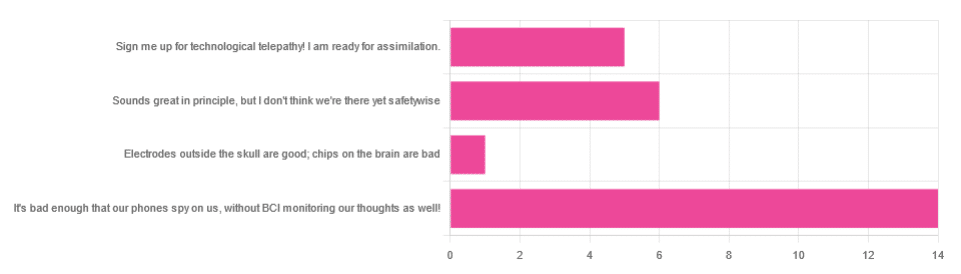

In yesterday’s newsletter, we asked you for your views on Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), such as the Utah Array and Neuralink’s chips on/in brains that allow direct communication between brains and computers, so that (for example) a paralysed person can use a device to communicate, or manipulate a prosthetic limb or two.

We didn’t get as many votes as usual; it’s possible that yesterday’s newsletter ended up in a lot of spam filters due to repeated use of a word in “extra ______ olive oil” in its main feature!

However, of the answers we did get…

- About 54% said “It’s bad enough that our phones spy on us, without BCI monitoring our thoughts as well!”

- About 23% said “Sounds great in principle, but I don’t think we’re there yet safetywise”

- About 19% said “Sign me up for technological telepathy! I am ready for assimilation”

- One (1) person said “Electrode outside the skull are good; chips on the brain are bad”

But what does the science say?

We’re not there yet safetywise: True or False?

True, in our opinion, when it comes to the latest implants, anyway. While it’s very difficult to prove a negative (it could be that everything goes perfectly in human trials), “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, and so far this seems to be lacking.

The stage before human trials is usually animal trials, starting with small creatures and working up to non-human primates if appropriate, before finally humans.

- Good news: the latest hot-topic BCI device (Neuralink) was tested on animals!

- Bad news: to say it did not go well would be an understatement

The Gruesome Story of How Neuralink’s Monkeys Actually Died

The above is a Wired article, and we tend to go for more objective sources, however we chose this one because it links to very many objective sources, including an open letter from the Physicians’ Committee for Responsible Medicine, which basically confirms everything in the Wired article. There are lots of links to primary (medical and legal) sources, too.

Electrodes outside the skull are good; chips on/in the brain are bad: True or False?

True or False depending on how they’re done. The Utah Array (an older BCI implant, now 20 years old, though it’s been updated many times since) has had a good safety record, after being used by a few dozen people with paralysis to control devices:

How the Utah Array is advancing BCI science

The Utah Array works on the same general principle as Neuralink, but the mechanics of its implementation are very different:

- The Utah Array involves a tiny bundle of microelectrodes (held together by a rigid structure that looks a bit like a nanoscale hairbrush) put in place by a brain surgeon, and that’s that.

- The Neuralink has a dynamic web of electrodes, implanted by a little robot that acts like a tiny sewing machine to implant many polymer threads, each containing its own a bunch of electrodes.

In theory, the latter is much more advanced. In practice, so far, the former has a much better safety record.

I am right to be a little worried about giving companies access to my brain: True or False?

True or False, depending on the nature of your concern.

For privacy: current BCI devices have quite simple switches operated consciously by the user. So while technically any such device that then runs its data through Bluetooth or WiFi could be hacked, this risk is no greater than using a wireless mouse and/or keyboard, because it has access to about the same amount of information.

For safety: yes, probably there is cause to be worried. Likely the first waves of commercial users of any given BCI device will be severely disabled people who are more likely to waive their rights in the hope of a life-changing assistance device, and likely some of those will suffer if things go wrong.

Which on the one hand, is their gamble to make. And on the other hand, makes rushing to human trials, for companies that do that, a little more predatory.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Truth About Handwashing

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Washing Our Hands Of It

In Tuesdays’s newsletter, we asked you how often you wash your hands, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of self-reported answers:

- About 54% said “More times per day than [the other options]”

- About 38% said “Whenever using the bathroom or kitchen

- About 5% said “Once or twice per day”

- Two (2) said “Only when visibly dirty”

- Two (2) said “I prefer to just use sanitizer gel”

What does the science have to say about this?

People lie about their handwashing habits: True or False?

True and False (since some people lie and some don’t), but there’s science to this too. Here’s a great study from 2021 that used various levels of confidentiality in questioning (i.e., there were ways of asking that made it either obvious or impossible to know who answered how), and found…

❝We analysed data of 1434 participants. In the direct questioning group 94.5% of the participants claimed to practice proper hand hygiene; in the indirect questioning group a significantly lower estimate of only 78.1% was observed.❞

Note: the abstract alone doesn’t make it clear how the anonymization worked (it is explained later in the paper), and it was noted as a limitation of the study that the participants may not have understood how it works well enough to have confidence in it, meaning that the 78.1% is probably also inflated, just not as much as the 94.5% in the direct questioning group.

Here’s a pop-science article that cites a collection of studies, finding such things as for example…

❝With the use of wireless devices to record how many people entered the restroom and used the pumps of the soap dispensers, researchers were able to collect data on almost 200,000 restroom trips over a three-month period.

The found that only 31% of men and 65% of women washed their hands with soap.❞

Source: Study: Men Wash Their Hands Much Less Often Than Women (And People Lie About Washing Their Hands)

Sanitizer gel does the job of washing one’s hands with soap: True or False?

False, though it’s still not a bad option for when soap and water aren’t available or practical. Here’s an educational article about the science of why this is so:

UCI Health | Soap vs. Hand Sanitizer

There’s also some consideration of lab results vs real-world results, because while in principle the alcohol gel is very good at killing most bacteria / inactivating most viruses, it can take up to 4 minutes of alcohol gel contact to do so, as in this study with flu viruses:

In contrast, 20 seconds of handwashing with soap will generally do the job.

Antibacterial soap is better than other soap: True or False?

False, because the main way that soap protects us is not in its antibacterial properties (although it does also destroy the surface membrane of some bacteria and for that matter viruses too, killing/inactivating them, respectively), but rather in how it causes pathogens to simply slide off during washing.

Here’s a study that found that handwashing with soap reduced disease incidence by 50–53%, and…

❝Incidence of disease did not differ significantly between households given plain soap compared with those given antibacterial soap.❞

Read more: Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial

Want to wash your hands more than you do?

There have been many studies into motivating people to wash their hands more (often with education and/or disgust-based shaming), but an effective method you can use for yourself at home is to simply buy more luxurious hand soap, and generally do what you can to make handwashing a more pleasant experience (taking a moment to let the water run warm is another good thing to do if that’s more comfortable for you).

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Beetroot Juice & Caffeine Work Better Than Either Alone

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Beetroot has many beneficial properties, which we’ve written about before:

Beetroot For More Than Just Your Blood Pressure

…and as for caffeine, it’s a mixed bag but for most people, the benefits of moderate caffeine use outweigh the risks:

Caffeine: Cognitive Enhancer Or Brain-Wrecker?

Now, caffeine’s less desirable effects can be mitigated somewhat by pairing it with l-theanine, as we’ve also discussed before:

L-Theanine: What’s The Tea? ← l-theanine also has many wonderful properties of its own, aside from its complementary effects when taken alongside caffeine

So, what’s the deal with caffeine and beetroot juice?

A performance-enhancing balancing act

Caffeine raises blood pressure, while beetroot lowers it, but there’s a lot more to it than that.

Researchers looked into the effects of caffeine and beetroot juice, together or separately, on athletic performance (in a 1000m run) in non-athletes.

They found:

- Caffeine alone enhanced second-run performance but not the first.

- Beetroot juice alone improved first-run performance but led to a performance decline after recovery.

- The caffeine + BJ combo resulted in the best initial and repeated 1000m run performances.

Specifically, they also noted:

- Caffeine alone caused higher blood lactate levels post-exercise.

- Beetroot juice increased muscle oxygenation by 25% during runs.

- The caffeine + BJ combo led to the highest post-exercise heart rate improvements.

You can read the paper in full here:

Caffeine and Beetroot Juice Optimize 1,000-m Performance: Shapley Additive Explanations Analysis

Now, maybe you don’t have a 1000m run to do, let alone multiple ones back-to-back, but most of us could sometimes do with an energy boost during the day, and this seems like an excellent way to get it.

That said, caffeine timing can be important too; midday is generally the best time for it, because:

- of course it should not be too late in the day, because the elimination half-life of caffeine (4–8 hours to eliminate just half of the caffeine, depending on genes, call it 6 hours as an average though honestly for most people it will either be 4 or 8, not 6) is such that it can easily interfere with sleep for most people

- because caffeine is an adenosine blocker, not an adenosine inhibitor, taking caffeine in the morning means either there’s no adenosine to block, or it’ll just “save” that adenosine for later, i.e. when the caffeine is eliminated, then the adenosine will kick in, meaning that your morning sleepiness has now been deferred to the afternoon, rather than eliminated.

Another reminder that caffeine is the “payday loan” of energy. So, midday it is. No morning sleepiness to defer, and yet also not so late as to interfere with sleep.

See also: Calculate (And Enjoy) The Perfect Night’s Sleep

Want to learn more?

Check out:

The Best Form Of Sugar For Energy During Exercise

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Dark Calories – by Dr. Catherine Shanahan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may be wondering: do we really need a 416-page book to say “don’t use vegetable oils”?

The author, who was a biochemist before becoming a family physician, takes a lot of care to explain in ways the non-chemists amongst us can understand (with molecular diagrams very well-labelled), exactly why certain seed/vegetable oils (both of those names being imprecise and unhelpful as umbrella terms) cause metabolic problems for us, when in contrast olive oil, avocado oil, and even peanut oil, do not.

Understanding is, for many, the root foundation of compliance. We are more likely to abide by rules we understand the logic behind, than seemingly arbitrary “thou shalt not…” proclamations.

So that’s an important strength of the book, demystifying various fats and how our body responds to them on a biochemical level, not just “is associated with such-and-such, based on observational population studies”. This kind of explanation clears up why, for example, seed oils correlate with obesity more than calories, sugar, wheat, or beef—having as it does to do with affecting our body’s ability to generate and use energy.

She also offers practical tips/reminders throughout, such as how “organic” does not necessarily mean “healthy” (indeed, many poisonous plants can be grown “organically”), and nor does “organic” mean “unrefined”, it speaks only for the conditions in which the raw product was first made, before other things were done to it later.

We learn a lot, too, about the processes of oxidation, the biochemistry behind that (more diagrams!), and of course the inflammatory response to same (an important factor in most if not all chronic disease).

The style is mostly very easy-to-read pop-science, though if you’re not a chemist, you’ll probably need to slow down for the biochemistry explanations (this reviewer certainly did).

Bottom line: this is more than just a litany against vegetable oils; it’s a ground-upwards education in metabolic biochemistry for the layperson, and what that means for us in terms of chronic disease risks.

Click here to check out Dark Calories, and learn what’s going on with these oils!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Anti-Stress Herb That Also Fights Cancer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What does Rhodiola rosea actually do, anyway?

Rhodiola rosea (henceforth, “rhodiola”) is a flowering herb whose roots have adaptogenic properties.

In the cold, mountainous regions of Europe and Asia where it grows, it has been used in herbal medicine for centuries to alleviate anxiety, fatigue, and depression.

What does the science say?

Well, let’s just say the science is more advanced than the traditional use:

❝In addition to its multiplex stress-protective activity, Rhodiola rosea extracts have recently demonstrated its anti-aging, anti-inflammation, immunostimulating, DNA repair and anti-cancer effects in different model systems❞

Nor is how it works a mystery, as the same paper explains:

❝Molecular mechanisms of Rhodiola rosea extracts’s action have been studied mainly along with one of its bioactive compounds, salidroside. Both Rhodiola rosea extracts and salidroside have contrasting molecular mechanisms on cancer and normal physiological functions.

For cancer, Rhodiola rosea extracts and salidroside inhibit the mTOR pathway and reduce angiogenesis through down-regulation of the expression of HIF-1α/HIF-2α.

For normal physiological functions, Rhodiola rosea extracts and salidroside activate the mTOR pathway, stimulate paracrine function and promote neovascularization by inhibiting PHD3 and stabilizing HIF-1α proteins in skeletal muscles❞

~ Ibid.

And, as for the question of “do the supplements work?”,

❝In contrast to many natural compounds, salidroside is water-soluble and highly bioavailable via oral administration❞

~ Ibid.

And as to how good it is:

❝Rhodiola rosea extracts and salidroside can impose cellular and systemic benefits similar to the effect of positive lifestyle interventions to normal physiological functions and for anti-cancer❞

~ Ibid.

Source: Rhodiola rosea: anti-stress, anti-aging, and immunostimulating properties for cancer chemoprevention

But that’s not all…

We can’t claim this as a research review if we only cite one paper (even if that paper has 144 citations of its own), and besides, it didn’t cover all the benefits yet!

Let’s first look at the science for the “traditional use” trio of benefits:

When you read those, what are your first thoughts?

Please don’t just take our word for things! Reading even just the abstracts (summaries) at the top of papers is a very good habit to get into, if you don’t have time (or easy access) to read the full text.

Reading the abstracts is also a very good way to know whether to take the time to read the whole paper, or whether it’s better to skip onto a different one.

- Perhaps you noticed that the paper we cited for anxiety was quite a small study.

- The fact is, while we found mountains of evidence for rhodiola’s anxiolytic (antianxiety) effects, they were all small and/or animal studies. So we picked a human study and went with it as illustrative.

- Perhaps you noticed that the paper we cited for fatigue pertained mostly to stress-related fatigue.

- This, we think, is a feature not a bug. After all, most of us experience fatigue because of the general everything of life, not because we just ran a literal marathon.

- Perhaps you noticed that the paper we cited for depression said it didn’t work as well as sertraline (a very common pharmaceutical SSRI antidepressant).

- But, it worked almost as well and it had far fewer adverse effects reported. Bear in mind, the side effects of antidepressants are the reason many people avoid them, or desist in taking them. So rhodiola working almost as well as sertraline for far fewer adverse effects, is quite a big deal!

Bonus features

Rhodiola also putatively offers protection against Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cerebrovascular disease in general:

Rosenroot (Rhodiola): Potential Applications in Aging-related Diseases

It may also be useful in the management of diabetes (types 1 and 2), but studies so far have only been animal studies, and/or in vitro studies. Here are two examples:

- Antihyperglycemic action of rhodiola-aqeous extract in type 1 diabetic rats

- Evaluation of Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola rosea for management of type 2 diabetes and hypertension

How much to take?

Dosages have varied a lot in studies. However, 120mg/day seems to cover most bases. It also depends on which of rhodiola’s 140 active compounds a particular benefit depends on, though salidroside and rosavin are the top performers.

Where to get it?

As ever, we don’t sell it (or anything else) but here’s an example product on Amazon.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

- Perhaps you noticed that the paper we cited for anxiety was quite a small study.

-

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck – by Mark Manson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may wonder from the title: is this book arguing that we should all be callous heartless monsters? And no, it is not.

Instead, author Mark Manson advocates for cynicism, but less in the manner of Scrooge, and more in the manner of Diogenes:

- That life will involve struggle, so we might as well at least choose our struggles.

- That we will make mistakes, so we might as well accept them as learning experiences.

- That we will love and we will lose, so we might as well do it right while we can.

In short, the book is less about not caring… And more about caring about the right things only.

So, what are “the right things”? Manson bids us decide for ourselves, but certainly has ideas and pointers, with regard to what may or may not be healthy values to pursue.

The style throughout is casual and almost conversational, without being overly padded. It makes for very easy reading.

If the book has a weak point, it’s that when it briefly makes a suprisingly prescriptive turn into recommending we take up Buddhism, it may feel a bit like our friend who wants us to join in the latest MLM scheme. But, he’s soon back on track.

Bottom line: if you ever find yourself stressed with living up to unwanted expectations—your own, other people’s, and society’s—this book can really help streamline things.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: