Dried Apricots vs Dried Prunes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing dried apricots to dried prunes, we picked the prunes.

Why?

First, let’s talk hydration. We’ve described both of these as “dried”, but prunes are by default dried plums, usually partially rehydrated. So, for fairness, on the other side of things we’re also looking at dried apricots, partially rehydrated. Otherwise, it would look (mass for mass or volume for volume) like one is seriously outstripping the other even if some metric were actually equal, just because of water-weight in one and not the other.

Illustrative example: consider, for example, that the sugar in a bunch of grapes or a handful of raisins can be the same, not because they magically got more sugary, but because the water was dried out, so per mass and per volume, there’s more sugar, proportionally.

Back to dried apricots and dried prunes…

You’ll often see these two next to each other in the heath food store, which is why we’re comparing them here.

Of course, if it is practical, please by all means enjoy fresh apricots and fresh plums. But we know that life is not always convenient, fruits are not in season growing in abundance in our gardens all year round, and sometimes we’re stood in the aisle of a grocery store, weighing up the dried fruit options.

- Apricots are well-known for their zinc, potassium, and vitamin A.

- Prunes are well-known for their fiber.

But that’s not the whole story…

- Apricots outperform prunes for vitamin A, and also vitamins C and E.

- Prunes take first place for vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, and K, and also for minerals calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and zinc.

- Prunes also have about 3x the fiber, which at the very least offsets the fact that they have 3x the sugar.

Once again, sugar in fruit is healthy (sugar in fruit juices is not*, though, so enjoy prunes rather than just prune juice, if you can) and can take its rightful place as providing a significant portion of our daily energy needs, if we let it.

*It’s the same sugar, just the manner of delivery changes what it does to our liver and our pancreas; see:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

In summary…

Dried apricots are great (fresh are even better), and yet prunes outperform them by most metrics on a like-for-like basis.

Prunes have, on balance, a lot more vitamins and minerals, as well as more fiber and energy.

Want to get some?

Your local supermarket probably has them, and if you prefer having them delivered to your door, then here’s an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

3 drugs that went from legal, to illegal, then back again

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cannabis, cocaine and heroin have interesting life stories and long rap sheets. We might know them today as illicit drugs, but each was once legal.

Then things changed. Racism and politics played a part in how we viewed them. We also learned more about their impact on health. Over time, they were declared illegal.

But decades later, these drugs and their derivatives are being used legally, for medical purposes.

Here’s how we ended up outlawing cannabis, cocaine and heroin, and what happened next.

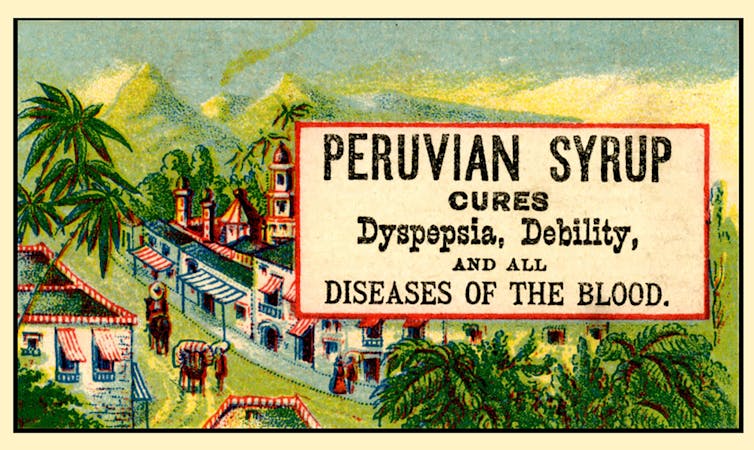

Peruvian Syrup, containing cocaine, was used to ‘cure’ a range of diseases. Smithsonian Museum of American History/Flickr Cannabis, religion and racism

Cannabis plants originated in central Asia, spread to North Africa, and then to the Americas. People grew cannabis for its hemp fibre, used to make ropes and sacks. But it also had other properties. Like many other ancient medical discoveries, it all started with religion.

Cannabis is mentioned in the Hindu texts known as the Vedas (1700-1100 BCE) as a sacred, feel-good plant. Cannabis or bhang is still used ritually in India today during festivals such as Shivratri and Holi.

From the late 1700s, the British in India started taxing cannabis products. They also noticed a high rate of “Indian hemp insanity” – including what we’d now recognise as psychosis – in the colony. By the late 1800s, a British government investigation found only heavy cannabis use seemed to affect people’s mental health.

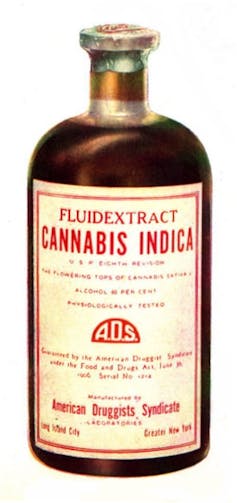

This drug bottle from the United States contains cannabis tincture. Wikimedia In the 1880s, cannabis was used therapeutically in the United States to treat tetanus, migraine and “insane delirium”. But not everyone agreed on (or even knew) the best dose. Local producers simply mixed up what they had into a tincture – soaking cannabis leaves and buds in alcohol to extract essential oils – and hoped for the best.

So how did cannabis go from a slightly useless legal drug to a social menace?

Some of it was from genuine health concerns about what was added to people’s food, drink and medicine.

In 1908 in Australia, New South Wales listed cannabis as an ingredient that could “adulterate” food and drink (along with opium, cocaine and chloroform). To sell the product legally, you had to tell the customers it contained cannabis.

Some of it was international politics. Moves to control cannabis use began in 1912 with the world’s first treaty against drug trafficking. The US and Italy both wanted cannabis included, but this didn’t happen until until 1925.

Some of it was racism. The word marihuana is Spanish for cannabis (later Anglicised to marijuana) and the drug became associated with poor migrants. In 1915, El Paso, Texas, on the Mexican border, was the first US municipality to ban the non-medical cannabis trade.

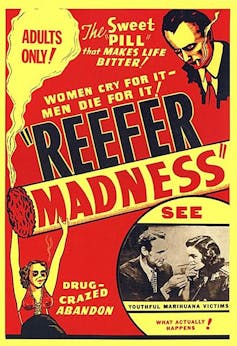

By the late 1930s, cannabis was firmly entrenched as a public menace and drug laws had been introduced across much of the US, Europe and (less quickly) Australia to prohibit its use. Cannabis was now a “poison” regulated alongside cocaine and opiates.

The 1936 movie Reefer Madness fuelled cannabis paranoia. Motion Picture Ventures/Wikimedia Commons The 1936 movie Reefer Madness was a high point of cannabis paranoia. Cannabis smoking was also part of other “suspect” new subcultures such as Black jazz, the 1950s Beatnik movement and US service personnel returning from Vietnam.

Today recreational cannabis use is associated with physical and mental harm. In the short term, it impairs your functioning, including your ability to learn, drive and pay attention. In the long term, harms include increasing the risk of psychosis.

But what about cannabis as a medicine? Since the 1980s there has been a change in mood towards experimenting with cannabis as a therapeutic drug. Medicinal cannabis products are those that contain cannabidiol (CBD) or tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Today in Australia and some other countries, these can be prescribed by certain doctors to treat conditions when other medicines do not work.

Medicinal cannabis has been touted as a treatment for some chronic conditions such as cancer pain and multiple sclerosis. But it’s not clear yet whether it’s effective for the range of chronic diseases it’s prescribed for. However, it does seem to improve the quality of life for people with some serious or terminal illnesses who are using other prescription drugs.

Cocaine, tonics and addiction

Several different species of the coca plant grow across Bolivia, Peru and Colombia. For centuries, local people chewed coca leaves or made them into a mildly stimulant tea. Coca and ayahuasca (a plant-based psychedelic) were also possibly used to sedate people before Inca human sacrifice.

In 1860, German scientist Albert Niemann (1834-1861) isolated the alkaloid we now call “cocaine” from coca leaves. Niemann noticed that applying it to the tongue made it feel numb.

But because effective anaesthetics such as ether and nitrous oxide had already been discovered, cocaine was mostly used instead in tonics and patent medicines.

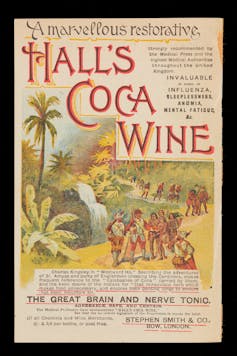

Hall’s Coca Wine was made from the leaves of the coca plant. Stephen Smith & Co/Wellcome Collection, CC BY Perhaps the most famous example was Coca-Cola, which contained cocaine when it was launched in 1886. But cocaine was used earlier, in 1860s Italy, in a drink called Vin Mariani – Pope Leo XIII was a fan.

With cocaine-based products easily available, it quickly became a drug of addiction.

Cocaine remained popular in the entertainment industry. Fictional detective Sherlock Holmes injected it, American actor Tallulah Bankhead swore by it, and novelist Agatha Christie used cocaine to kill off some of her characters.

In 1914, cocaine possession was made illegal in the US. After the hippy era of the 1960s and 1970s, cocaine became the “it” drug of the yuppie 1980s. “Crack” cocaine also destroyed mostly Black American urban communities.

Cocaine use is now associated with physical and mental harms. In the short and long term, it can cause problems with your heart and blood pressure and cause organ damage. At its worst, it can kill you. Right now, illegal cocaine production and use is also surging across the globe.

But cocaine was always legal for medical and surgical use, most commonly in the form of cocaine hydrochloride. As well as acting as a painkiller, it’s a vasoconstrictor – it tightens blood vessels and reduces bleeding. So it’s still used in some types of surgery.

Heroin, coughing and overdoses

Opium has been used for pain relief ever since people worked out how to harvest the sap of the opium poppy. By the 19th century, addictive and potentially lethal opium-based products such as laudanum were widely available across the United Kingdom, Europe and the US. Opium addiction was also a real problem.

Because of this, scientists were looking for safe and effective alternatives for pain relief and to help people cure their addictions.

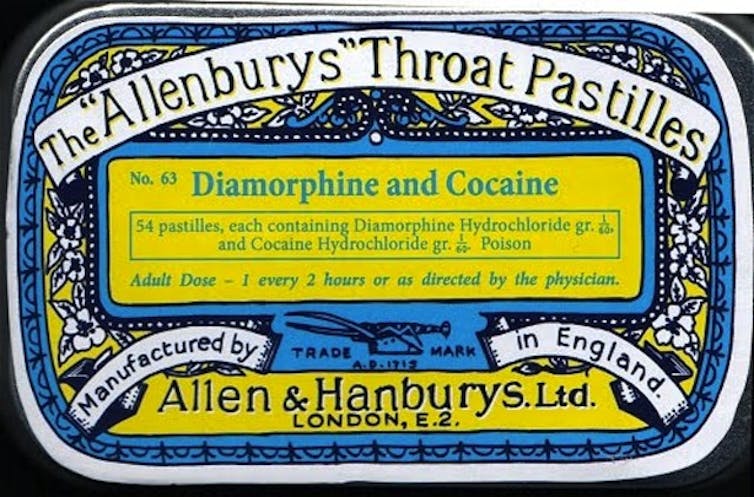

In 1874, English chemist Charles Romley Alder Wright (1844-1894) created diacetylmorphine (also known as diamorphine). Drug firm Bayer thought it might be useful in cough medicines, gave it the brand name Heroin and put it on the market in 1898. It made chest infections worse.

Allenburys Throat Pastilles contained heroin and cocaine. Seth Anderson/Flickr, CC BY-NC Although diamorphine was created with good intentions, this opiate was highly addictive. Shortly after it came on the market, it became clear that it was every bit as addictive as other opiates. This coincided with international moves to shut down the trade in non-medical opiates due to their devastating effect on China and other Asian countries.

Like cannabis, heroin quickly developed radical chic. The mafia trafficked into the US and it became popular in the Harlem jazz scene, beatniks embraced it and US servicemen came back from Vietnam addicted to it. Heroin also helped kill US singers Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison.

Today, we know heroin use and addiction contributes to a range of physical and mental health problems, as well as death from overdose.

However, heroin-related harm is now being outpaced by powerful synthetic opioids such as oxycodone, fentanyl, and the nitazene group of drugs. In Australia, there were more deaths and hospital admissions from prescription opiate overdoses than from heroin overdoses.

In a nutshell

Not all medicines have a squeaky-clean history. And not all illicit drugs have always been illegal.

Drugs’ legal status and how they’re used are shaped by factors such as politics, racism and social norms of the day, as well as their impact on health.

Philippa Martyr, Lecturer, Pharmacology, Women’s Health, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Sleeping on Your Back after 50; Yay or Nay?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sleeping Differently After 50

Sleeping is one of those things that, at any age, can be hard to master. Some of our most popular articles have been on getting better sleep, and effective sleep aids, and we’ve had a range of specific sleep-related questions, like whether air purifiers actually improve your sleep.

But perhaps there’s an underlying truth hidden in our opening sentence…is sleeping consistently difficult because the way we sleep should change according to our age?

Inspired by Brad and Mike’s video below (which was published to their 5 million+ subscribers!), there are 4 main elements to consider when sleeping on your back after you’ve hit the 50-year mark:

- Degenerative Disk Disease: As you age, your spine may start to show signs of wear and tear, which directly affects comfort while lying on your back.

- Sleep Apnea and Snoring: Sleep Apnea and snoring become more of an issue with age, and sleeping on your back can exacerbate these problems; when you sleep on your back, the soft tissues in your throat, as well as your tongue, “fall back” and partly obstruct your the airway.

- Spinal Stenosis: Spinal Stenosis–the often-age-related narrowing of your spinal canal–can put pressure on the nerves that travel through the spine, which equally makes back-sleeping harder.

- GERD: The all-too-familiar gastroesophageal reflux disease can be more problematic when lying flat on your back, as doing so can allow easy access for stomach acid to move upwards.

Alternatives to Back Sleeping

Referencing the Mayo Clinic’s Sleep Facility’s director, Dr. Virend Somers, today’s video suggests a simple solution: sleeping on your side. The video goes into a bit more detail but, as you know, here at 10almonds we like to cut to the chase.

Modifications for Back Sleeping

If you’re a lifelong back-sleeping and cannot bear the idea of changing to your side, or your stomach, then there are a few modifications that you can make to ease any pain and discomfort.

Most solutions revolve around either leg wedges or pillow adjustments. For instance, if you’re suffering from back pain, try propping your knees up. Or if GERD is your worst enemy, a wedge pillow could help keep that acid down.

As can be expected, the video dives into more detail:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

Does Music Really Benefit The Brain?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝Is it actually beneficial for the brain to listen to music, or is it just in line with any relaxing activity? And what kind of music is most beneficial❞

The short answer, first of all, is that it is indeed beneficial.

One reason for this without having to get very deep into it, is that a very important thing for general brain health is using it, and that means lighting up all areas of your brain.

Now, we all lead different lives and thus different parts of our brains will get relatively more resources than others depending on what we do with them, and that’s ok.

For example, if you were to scan this writer’s polyglot brain, you’d surely find overdevelopment in areas associated with language use and verbal memory, but if you were to scan a taxi-driver’s brain, then it’d be spatial reasoning and spatial memory that’s overpowered, and for a visual artist, it may be visual processing and creativity that’s enhanced. A musician’s brain? Fine motor skills, auditory processing, auditory memory.

Now, for those of us who aren’t musicians, how then can we light up areas associated with music? By listening to music, of course. It won’t give us the fine motor skills of a concert violinist, but the other areas we mentioned will get a boost.

See also: How To Engage Your Whole Brain ← this covers music too, but it’s about (as the title suggests) the whole brain, so check it out and see if there are any areas you’ve been neglecting!

There are other benefits too, though, including engaging our parasympathetic nervous system, which is good for our heart, gut, brain, and general health—especially if we sing or hum along to the music:

The Science Of Sounds ← this also covers the science (yes, science) of mantra meditation vs music

As for “and what kind of music is most beneficial”, we’d hypothesize that a variety is best, just like with food!

However, there are some considerations to bear in mind, with science to support them. For example…

About tempo:

❝EEG analysis revealed significant changes in brainwave signals across different frequency bands under different tempi.

For instance, slow tempo induced higher Theta and Alpha power in the frontal region, while fast tempo increased Beta and Gamma band power.

Moreover, fast tempo enhanced the average connectivity strength in the frontal, temporal, and occipital regions, and increased phase synchrony value (PLV) between the frontal and parietal regions.❞

Read in full: Music tempo modulates emotional states as revealed through EEG insights

And if you’re wondering about those different brainwave bands, check out:

- How to get many benefits of sleep, while awake! Non-Sleep Deep Rest: A Neurobiologist’s Take ← although it’s not in the title, this does also cover the different brain wave bands

- Alpha, beta, theta: what are brain states and brain waves? And can we control them?

Additionally, if you just want science-backed relaxation, the following 8-minute soundscape was developed by sound technicians working with a team of psychologists and neurologists.

It’s been clinically tested, and found to have a much more relaxing effect (in objective measures of lowering heart rate and lowering cortisol levels, as well as in subjective self-reports) than merely “relaxing music”.

Try it and see for yourself:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

For much deeper dive into the effect of music on the brain, check out this book we reviewed a while back, by an accomplished musician and neuroscientist (that’s one person, who is both things):

This Is Your Brain on Music – by Dr. Daniel Levitin

Enjoy!

And now for a bonus item…

A s a bit of reader feedback prompted some interesting thoughts:

❝You erred on the which is better section. Read this carefully :Looking at minerals, grapes have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while grapes have more potassium and manganese. A clear win for strawberries here.❞

You’re quite right; thank you for pointing it out, and kindly pardon the typo, which has now been corrected!

The reason for the mistake was because when I (writer responsible for it here, hi) was writing this, I had the information for both fruits in front of me, but the information for grapes was on the right in my field of vision, so I errantly put it on the right on the page, too, while also accidentally crediting strawberries’ minerals to grapes, since strawberries’ data was on the left in my field a vision.

The reason for explaining this: it’s a quirky, very human way to err, in an era when a lot of web content is AI-generated with very different kinds of mistakes (usually because AI is very bad at checking sources, so will confidently state something as true despite the fact that the source was The Onion, or Clickhole, or someone’s facetiously joking answer on Quora, for example).

All in all, while we try to not make typos, we’d rather such human errors than doing like an AI and confidently telling you that Amanita phalloides mushrooms are a rich source of magnesium, and also delicious (they are, reportedly, but they are also the most deadly mushroom on the face of the Earth, also known as the Death Cap mushroom).

In any case, here’s the corrected version of the grapes vs strawberries showdown:

Grapes vs Strawberries – Which is Healthier?

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

People with dementia aren’t currently eligible for voluntary assisted dying. Should they be?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dementia is the second leading cause of death for Australians aged over 65. More than 421,000 Australians currently live with dementia and this figure is expected to almost double in the next 30 years.

There is ongoing public discussion about whether dementia should be a qualifying illness under Australian voluntary assisted dying laws. Voluntary assisted dying is now lawful in all six states, but is not available for a person living with dementia.

The Australian Capital Territory has begun debating its voluntary assisted dying bill in parliament but the government has ruled out access for dementia. Its view is that a person should retain decision-making capacity throughout the process. But the bill includes a requirement to revisit the issue in three years.

The Northern Territory is also considering reform and has invited views on access to voluntary assisted dying for dementia.

Several public figures have also entered the debate. Most recently, former Australian Chief Scientist, Ian Chubb, called for the law to be widened to allow access.

Others argue permitting voluntary assisted dying for dementia would present unacceptable risks to this vulnerable group.

Inside Creative House/Shutterstock Australian laws exclude access for dementia

Current Australian voluntary assisted dying laws exclude access for people who seek to qualify because they have dementia.

In New South Wales, the law specifically states this.

In the other states, this occurs through a combination of the eligibility criteria: a person whose dementia is so advanced that they are likely to die within the 12 month timeframe would be highly unlikely to retain the necessary decision-making capacity to request voluntary assisted dying.

This does not mean people who have dementia cannot access voluntary assisted dying if they also have a terminal illness. For example, a person who retains decision-making capacity in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease with terminal cancer may access voluntary assisted dying.

What happens internationally?

Voluntary assisted dying laws in some other countries allow access for people living with dementia.

One mechanism, used in the Netherlands, is through advance directives or advance requests. This means a person can specify in advance the conditions under which they would want to have voluntary assisted dying when they no longer have decision-making capacity. This approach depends on the person’s family identifying when those conditions have been satisfied, generally in consultation with the person’s doctor.

Another approach to accessing voluntary assisted dying is to allow a person with dementia to choose to access it while they still have capacity. This involves regularly assessing capacity so that just before the person is predicted to lose the ability to make a decision about voluntary assisted dying, they can seek assistance to die. In Canada, this has been referred to as the “ten minutes to midnight” approach.

But these approaches have challenges

International experience reveals these approaches have limitations. For advance directives, it can be difficult to specify the conditions for activating the advance directive accurately. It also requires a family member to initiate this with the doctor. Evidence also shows doctors are reluctant to act on advance directives.

Particularly challenging are scenarios where a person with dementia who requested voluntary assisted dying in an advance directive later appears happy and content, or no longer expresses a desire to access voluntary assisted dying.

What if the person changes their mind? Jokiewalker/Shutterstock Allowing access for people with dementia who retain decision-making capacity also has practical problems. Despite regular assessments, a person may lose capacity in between them, meaning they miss the window before midnight to choose voluntary assisted dying. These capacity assessments can also be very complex.

Also, under this approach, a person is required to make such a decision at an early stage in their illness and may lose years of otherwise enjoyable life.

Some also argue that regardless of the approach taken, allowing access to voluntary assisted dying would involve unacceptable risks to a vulnerable group.

More thought is needed before changing our laws

There is public demand to allow access to voluntary assisted dying for dementia in Australia. The mandatory reviews of voluntary assisted dying legislation present an opportunity to consider such reform. These reviews generally happen after three to five years, and in some states they will occur regularly.

The scope of these reviews can vary and sometimes governments may not wish to consider changes to the legislation. But the Queensland review “must include a review of the eligibility criteria”. And the ACT bill requires the review to consider “advanced care planning”.

Both reviews would require consideration of who is able to access voluntary assisted dying, which opens the door for people living with dementia. This is particularly so for the ACT review, as advance care planning means allowing people to request voluntary assisted dying in the future when they have lost capacity.

The legislation undergoes a mandatory review. Jenny Sturm/Shutterstock This is a complex issue, and more thinking is needed about whether this public desire for voluntary assisted dying for dementia should be implemented. And, if so, how the practice could occur safely, and in a way that is acceptable to the health professionals who will be asked to provide it.

This will require a careful review of existing international models and their practical implementation as well as what would be feasible and appropriate in Australia.

Any future law reform should be evidence-based and draw on the views of people living with dementia, their family caregivers, and the health professionals who would be relied on to support these decisions.

Ben White, Professor of End-of-Life Law and Regulation, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology; Casey Haining, Research Fellow, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology; Lindy Willmott, Professor of Law, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology, Queensland University of Technology, and Rachel Feeney, Postdoctoral research fellow, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

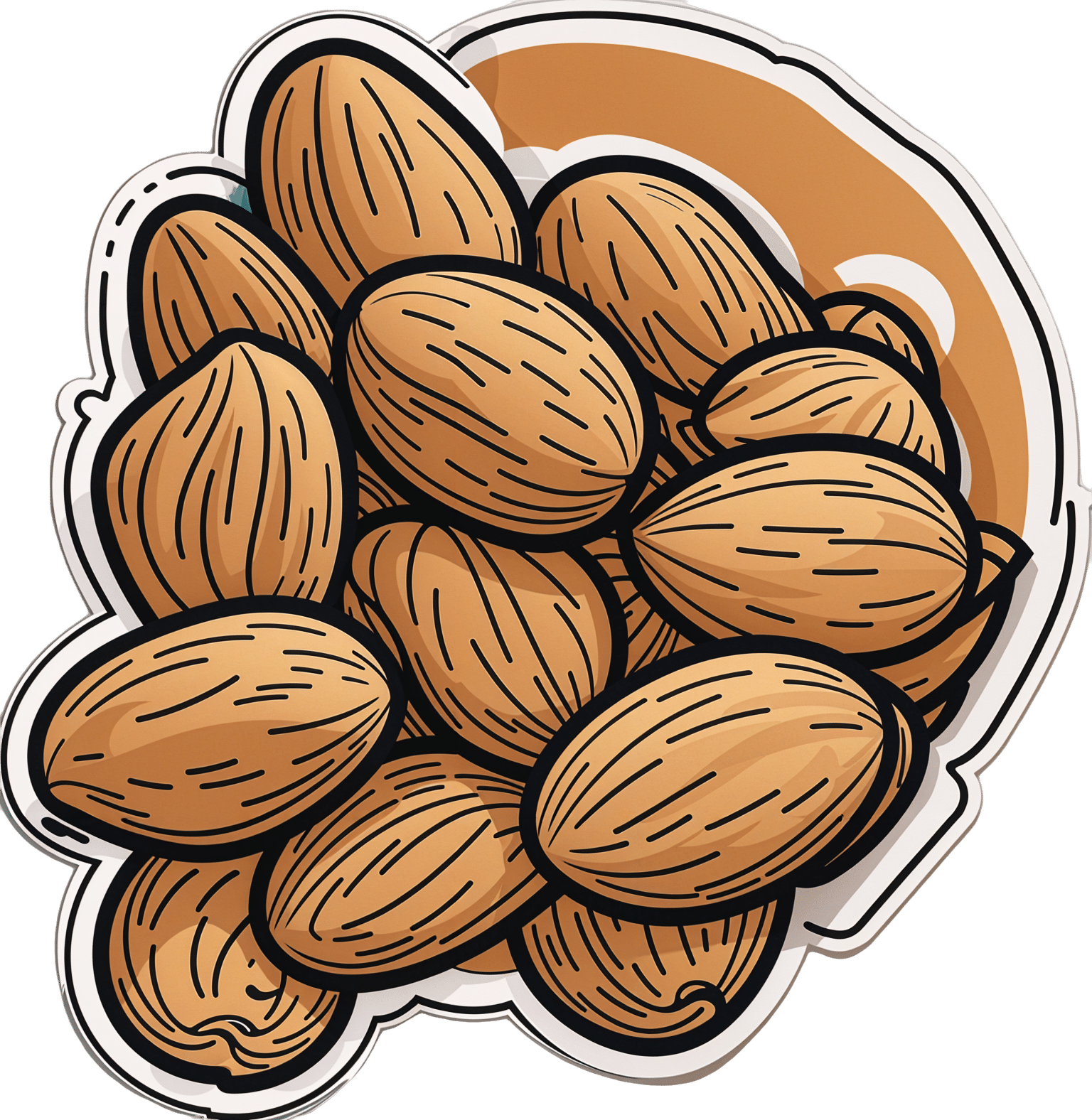

Why ’10almonds’? Newsletter Name Explained

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day!

Each Thursday, we respond to subscriber questions and requests! If it’s something small, we’ll answer it directly; if it’s something bigger, we’ll do a main feature in a follow-up day instead!

So, no question/request to big or small; they’ll just get sorted accordingly

Remember, you can always hit reply to any of our emails, or use the handy feedback widget at the bottom. We always look forward to hearing from you!

Q: Why is your newsletter called 10almonds? Maybe I missed it in the intro email, but my curiosity wants to know the significance. Thanks!”

It’s a reference to a viral Facebook hoax! There was a post going around that claimed:

❝HEADACHE REMEDY. Eat 10–12 almonds, the equivalent of two aspirins, next time you have a headache❞ ← not true!

It made us think about how much health-related disinformation there was online… So, calling ourselves 10almonds was a bit of a tongue-in-cheek reference to that story… but also a reminder to ourselves:

We must always publish information with good scientific evidence behind it!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How much time should you spend sitting versus standing? New research reveals the perfect mix for optimal health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People have a pretty intuitive sense of what is healthy – standing is better than sitting, exercise is great for overall health and getting good sleep is imperative.

However, if exercise in the evening may disrupt our sleep, or make us feel the need to be more sedentary to recover, a key question emerges – what is the best way to balance our 24 hours to optimise our health?

Our research attempted to answer this for risk factors for heart disease, stroke and diabetes. We found the optimal amount of sleep was 8.3 hours, while for light activity and moderate to vigorous activity, it was best to get 2.2 hours each.

Finding the right balance

Current health guidelines recommend you stick to a sensible regime of moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity 2.5–5 hours per week.

However mounting evidence now suggests how you spend your day can have meaningful ramifications for your health. In addition to moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity, this means the time you spend sitting, standing, doing light physical activity (such as walking around your house or office) and sleeping.

Our research looked at more than 2,000 adults who wore body sensors that could interpret their physical behaviours, for seven days. This gave us a sense of how they spent their average 24 hours.

At the start of the study participants had their waist circumference, blood sugar and insulin sensitivity measured. The body sensor and assessment data was matched and analysed then tested against health risk markers — such as a heart disease and stroke risk score — to create a model.

Using this model, we fed through thousands of permutations of 24 hours and found the ones with the estimated lowest associations with heart disease risk and blood-glucose levels. This created many optimal mixes of sitting, standing, light and moderate intensity activity.

When we looked at waist circumference, blood sugar, insulin sensitivity and a heart disease and stroke risk score, we noted differing optimal time zones. Where those zones mutually overlapped was ascribed the optimal zone for heart disease and diabetes risk.

You’re doing more physical activity than you think

We found light-intensity physical activity (defined as walking less than 100 steps per minute) – such as walking to the water cooler, the bathroom, or strolling casually with friends – had strong associations with glucose control, and especially in people with type 2 diabetes. This light-intensity physical activity is likely accumulated intermittently throughout the day rather than being a purposeful bout of light exercise.

Our experimental evidence shows that interrupting our sitting regularly with light-physical activity (such as taking a 3–5 minute walk every hour) can improve our metabolism, especially so after lunch.

While the moderate-to-vigorous physical activity time might seem a quite high, at more than 2 hours a day, we defined it as more than 100 steps per minute. This equates to a brisk walk.

It should be noted that these findings are preliminary. This is the first study of heart disease and diabetes risk and the “optimal” 24 hours, and the results will need further confirmation with longer prospective studies.

The data is also cross-sectional. This means that the estimates of time use are correlated with the disease risk factors, meaning it’s unclear whether how participants spent their time influences their risk factors or whether those risk factors influence how someone spends their time.

Australia’s adult physical activity guidelines need updating

Australia’s physical activity guidelines currently only recommend exercise intensity and time. A new set of guidelines are being developed to incorporate 24-hour movement. Soon Australians will be able to use these guidelines to examine their 24 hours and understand where they can make improvements.

While our new research can inform the upcoming guidelines, we should keep in mind that the recommendations are like a north star: something to head towards to improve your health. In principle this means reducing sitting time where possible, increasing standing and light-intensity physical activity, increasing more vigorous intensity physical activity, and aiming for a healthy sleep of 7.5–9 hours per night.

Beneficial changes could come in the form of reducing screen time in the evening or opting for an active commute over driving commute, or prioritising an earlier bed time over watching television in the evening.

It’s also important to acknowledge these are recommendations for an able adult. We all have different considerations, and above all, movement should be fun.

Christian Brakenridge, Postdoctoral research fellow at Swinburne University Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: