Why scrapping the term ‘long COVID’ would be harmful for people with the condition

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The assertion from Queensland’s chief health officer John Gerrard that it’s time to stop using the term “long COVID” has made waves in Australian and international media over recent days.

Gerrard’s comments were related to new research from his team finding long-term symptoms of COVID are similar to the ongoing symptoms following other viral infections.

But there are limitations in this research, and problems with Gerrard’s argument we should drop the term “long COVID”. Here’s why.

A bit about the research

The study involved texting a survey to 5,112 Queensland adults who had experienced respiratory symptoms and had sought a PCR test in 2022. Respondents were contacted 12 months after the PCR test. Some had tested positive to COVID, while others had tested positive to influenza or had not tested positive to either disease.

Survey respondents were asked if they had experienced ongoing symptoms or any functional impairment over the previous year.

The study found people with respiratory symptoms can suffer long-term symptoms and impairment, regardless of whether they had COVID, influenza or another respiratory disease. These symptoms are often referred to as “post-viral”, as they linger after a viral infection.

Gerrard’s research will be presented in April at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. It hasn’t been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

After the research was publicised last Friday, some experts highlighted flaws in the study design. For example, Steven Faux, a long COVID clinician interviewed on ABC’s television news, said the study excluded people who were hospitalised with COVID (therefore leaving out people who had the most severe symptoms). He also noted differing levels of vaccination against COVID and influenza may have influenced the findings.

In addition, Faux pointed out the survey would have excluded many older people who may not use smartphones.

The authors of the research have acknowledged some of these and other limitations in their study.

Ditching the term ‘long COVID’

Based on the research findings, Gerrard said in a press release:

We believe it is time to stop using terms like ‘long COVID’. They wrongly imply there is something unique and exceptional about longer term symptoms associated with this virus. This terminology can cause unnecessary fear, and in some cases, hypervigilance to longer symptoms that can impede recovery.

But Gerrard and his team’s findings cannot substantiate these assertions. Their survey only documented symptoms and impairment after respiratory infections. It didn’t ask people how fearful they were, or whether a term such as long COVID made them especially vigilant, for example.

New Africa/Shutterstock

In discussing Gerrard’s conclusions about the terminology, Faux noted that even if only 3% of people develop long COVID (the survey found 3% of people had functional limitations after a year), this would equate to some 150,000 Queenslanders with the condition. He said:

To suggest that by not calling it long COVID you would be […] somehow helping those people not to focus on their symptoms is a curious conclusion from that study.

Another clinician and researcher, Philip Britton, criticised Gerrard’s conclusion about the language as “overstated and potentially unhelpful”. He noted the term “long COVID” is recognised by the World Health Organization as a valid description of the condition.

A cruel irony

An ever-growing body of research continues to show how COVID can cause harm to the body across organ systems and cells.

We know from the experiences shared by people with long COVID that the condition can be highly disabling, preventing them from engaging in study or paid work. It can also harm relationships with their friends, family members, and even their partners.

Despite all this, people with long COVID have often felt gaslit and unheard. When seeking treatment from health-care professionals, many people with long COVID report they have been dismissed or turned away.

Last Friday – the day Gerrard’s comments were made public – was actually International Long COVID Awareness Day, organised by activists to draw attention to the condition.

The response from people with long COVID was immediate. They shared their anger on social media about Gerrard’s comments, especially their timing, on a day designed to generate greater recognition for their illness.

Since the start of the COVID pandemic, patient communities have fought for recognition of the long-term symptoms many people faced.

The term “long COVID” was in fact coined by people suffering persistent symptoms after a COVID infection, who were seeking words to describe what they were going through.

The role people with long COVID have played in defining their condition and bringing medical and public attention to it demonstrates the possibilities of patient-led expertise. For decades, people with invisible or “silent” conditions such as ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) have had to fight ignorance from health-care professionals and stigma from others in their lives. They have often been told their disabling symptoms are psychosomatic.

Gerrard’s comments, and the media’s amplification of them, repudiates the term “long COVID” that community members have chosen to give their condition an identity and support each other. This is likely to cause distress and exacerbate feelings of abandonment.

Terminology matters

The words we use to describe illnesses and conditions are incredibly powerful. Naming a new condition is a step towards better recognition of people’s suffering, and hopefully, better diagnosis, health care, treatment and acceptance by others.

The term “long COVID” provides an easily understandable label to convey patients’ experiences to others. It is well known to the public. It has been routinely used in news media reporting and and in many reputable medical journal articles.

Most importantly, scrapping the label would further marginalise a large group of people with a chronic illness who have often been left to struggle behind closed doors.

Deborah Lupton, SHARP Professor, Vitalities Lab, Centre for Social Research in Health and Social Policy Centre, and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Yes, adults can develop food allergies. Here are 4 types you need to know about

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you didn’t have food allergies as a child, is it possible to develop them as an adult? The short answer is yes. But the reasons why are much more complicated.

Preschoolers are about four times more likely to have a food allergy than adults and are more likely to grow out of it as they get older.

It’s hard to get accurate figures on adult food allergy prevalence. The Australian National Allergy Council reports one in 50 adults have food allergies. But a US survey suggested as many as one in ten adults were allergic to at least one food, with some developing allergies in adulthood.

What is a food allergy

Food allergies are immune reactions involving immunoglobulin E (IgE) – an antibody that’s central to triggering allergic responses. These are known as “IgE-mediated food allergies”.

Food allergy symptoms that are not mediated by IgE are usually delayed reactions and called food intolerances or hypersensitivity.

Food allergy symptoms can include hives, swelling, difficulty swallowing, vomiting, throat or chest tightening, trouble breathing, chest pain, rapid heart rate, dizziness, low blood pressure or anaphylaxis.

Symptoms include hives. wisely/Shutterstock IgE-mediated food allergies can be life threatening, so all adults need an action management plan developed in consultation with their medical team.

Here are four IgE-mediated food allergies that can occur in adults – from relatively common ones to rare allergies you’ve probably never heard of.

1. Single food allergies

The most common IgE-mediated food allergies in adults in a US survey were to:

- shellfish (2.9%)

- cow’s milk (1.9%)

- peanut (1.8%)

- tree nuts (1.2%)

- fin fish (0.9%) like barramundi, snapper, salmon, cod and perch.

In these adults, about 45% reported reacting to multiple foods.

This compares to most common childhood food allergies: cow’s milk, egg, peanut and soy.

Overall, adult food allergy prevalence appears to be increasing. Compared to older surveys published in 2003 and 2004, peanut allergy prevalence has increased about three-fold (from 0.6%), while tree nuts and fin fish roughly doubled (from 0.5% each), with shellfish similar (2.5%).

While new adult-onset food allergies are increasing, childhood-onset food allergies are also more likely to be retained into adulthood. Possible reasons for both include low vitamin D status, lack of immune system challenges due to being overly “clean”, heightened sensitisation due to allergen avoidance, and more frequent antibiotic use.

Some adults develop allergies to cow’s milk, while others retain their allergy from childhood. Sarah Swinton/Unsplash 2. Tick-meat allergy

Tick-meat allergy, also called α-Gal syndrome or mammalian meat allergy, is an allergic reaction to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose, or α-Gal for short.

Australian immunologists first reported links between α-Gal syndrome and tick bites in 2009, with cases also reported in the United States, Japan, Europe and South Africa. The US Centers for Disease Control estimates about 450,000 Americans could be affected.

The α-Gal contains a carbohydrate molecule that is bound to a protein molecule in mammals.

The IgE-mediated allergy is triggered after repeated bites from ticks or chigger mites that have bitten those mammals. When tick saliva crosses into your body through the bite, antibodies to α-Gal are produced.

When you subsequently eat foods that contain α-Gal, the allergy is triggered. These triggering foods include meat (lamb, beef, pork, rabbit, kangaroo), dairy products (yoghurt, cheese, ice-cream, cream), animal-origin gelatin added to gummy foods (jelly, lollies, marshmallow), prescription medications and over-the counter supplements containing gelatin (some antibiotics, vitamins and other supplements).

Tick-meat allergy reactions can be hard to recognise because they’re usually delayed, and they can be severe and include anaphylaxis. Allergy organisations produce management guidelines, so always discuss management with your doctor.

3. Fruit-pollen allergy

Fruit-pollen allergy, called pollen food allergy syndrome, is an IgE-mediated allergic reaction.

In susceptible adults, pollen in the air provokes the production of IgE antibodies to antigens in the pollen, but these antigens are similar to ones found in some fruits, vegetables and herbs. The problem is that eating those plants triggers an allergic reaction.

The most allergenic tree pollens are from birch, cypress, Japanese cedar, latex, grass, and ragweed. Their pollen can cross-react with fruit and vegetables, including kiwi, banana, mango, avocado, grapes, celery, carrot and potato, and some herbs such as caraway, coriander, fennel, pepper and paprika.

Fruit-pollen allergy is not common. Prevalence estimates are between 0.03% and 8% depending on the country, but it can be life-threatening. Reactions range from itching or tingling of lips, mouth, tongue and throat, called oral allergy syndrome, to mild hives, to anaphylaxis.

4. Food-dependent, exercise-induced food allergy

During heavy exercise, the stomach produces less acid than usual and gut permeability increases, meaning that small molecules in your gut are more likely to escape across the membrane into your blood. These include food molecules that trigger an IgE reaction.

If the person already has IgE antibodies to the foods eaten before exercise, then the risk of triggering food allergy reactions is increased. This allergy is called food-dependent exercise-induced allergy, with symptoms ranging from hives and swelling, to difficulty breathing and anaphylaxis.

This type of allergy is extremely rare. Ben O’Sullivan/Unsplash Common trigger foods include wheat, seafood, meat, poultry, egg, milk, nuts, grapes, celery and other foods, which could have been eaten many hours before exercising.

To complicate things even further, allergic reactions can occur at lower levels of trigger-food exposure, and be more severe if the person is simultaneously taking non-steroidal inflammatory medications like aspirin, drinking alcohol or is sleep-deprived.

Food-dependent exercise-induced allergy is extremely rare. Surveys have estimated prevalence as between one to 17 cases per 1,000 people worldwide with the highest prevalence between the teenage years to age 35. Those affected often have other allergic conditions such as hay fever, asthma, allergic conjunctivitis and dermatitis.

Allergies are a growing burden

The burden on physical health, psychological health and health costs due to food allergy is increasing. In the US, this financial burden was estimated as $24 billion per year.

Adult food allergy needs to be taken seriously and those with severe symptoms should wear a medical information bracelet or chain and carry an adrenaline auto-injector pen. Concerningly, surveys suggest only about one in four adults with food allergy have an adrenaline pen.

If you have an IgE-mediated food allergy, discuss your management plan with your doctor. You can also find more information at Allergy and Anaphylaxis Australia.

Clare Collins, Laureate Professor in Nutrition and Dietetics, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Eat All You Want (But Wisely)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Some Surprising Truths About Hunger And Satiety

This is Dr. Barbara Rolls. She’s Professor and Guthrie Chair in Nutritional Sciences, and Director of the Laboratory for the Study of Human Ingestive Behavior at Pennsylvania State University, after graduating herself from Oxford and Cambridge (yes, both). Her “awards and honors” take up four A4 pages, so we won’t list them all here.

Most importantly, she’s an expert on hunger, satiety, and eating behavior in general.

What does she want us to know?

First and foremost: you cannot starve yourself thin, unless you literally starve yourself to death.

What this is about: any weight lost due to malnutrition (“not eating enough” is malnutrition) will always go back on once food becomes available. So unless you die first (not a great health plan), merely restricting good will always result in “yo-yo dieting”.

So, to avoid putting the weight back on and feeling miserable every day along the way… You need to eat as much as you feel you need.

But, there’s a trick here (it’s about making you genuinely feel you need less)!

Your body is an instrument—so play it

Your body is the tool you use to accomplish pretty much anything you do. It is, in large part, at your command. Then there are other parts you can’t control directly.

Dr. Rolls advises taking advantage of the fact that much of your body is a mindless machine that will simply follow instructions given.

That includes instructions like “feel hungry” or “feel full”. But how to choose those?

Volume matters

An important part of our satiety signalling is based on a physical sensation of fullness. This, by the way, is why bariatric surgery (making a stomach a small fraction of the size it was before) works. It’s not that people can’t eat more (the stomach is stretchy and can also be filled repeatedly), it’s that they don’t want to eat more because the pressure sensors around the stomach feel full, and signal the hormone leptin to tell the brain we’re full now.

Now consider:

- On the one hand, 20 grapes, fresh and bursting with flavor

- On the other hand, 20 raisins (so, dried grapes), containing the same calories

Which do you think will get the leptin flowing sooner? Of course, the fresh grapes, because of the volume.

So if you’ve ever seen those photos that show two foods side by side with the same number of calories but one is much larger (say, a small slice of pizza or a big salad), it’s not quite the cheap trick that it might have appeared.

Or rather… It is a cheap trick; it’s just a cheap trick that works because your stomach is quite a simple organ.

So, Dr. Rolls’ advice: generally speaking, go for voluminous food. Fruit is great from this, because there’s so much water. Air-popped popcorn also works great. Vegetables, too.

Water matters, but differently than you might think

A well-known trick is to drink water before and with a meal. That’s good, it’s good to be hydrated. However, it can be better. Dr. Rolls did an experiment:

The design:

❝Subjects received 1 of 3 isoenergetic (1128 kJ) preloads 17 min before lunch on 3 d and no preload on 1 d.

The preloads consisted of 1) chicken rice casserole, 2) chicken rice casserole served with a glass of water (356 g), and 3) chicken rice soup.

The soup contained the same ingredients (type and amount) as the casserole that was served with water.❞

The results:

❝Decreasing the energy density of and increasing the volume of the preload by adding water to it significantly increased fullness and reduced hunger and subsequent energy intake at lunch.

The equivalent amount of water served as a beverage with a food did not affect satiety.❞

The conclusion:

❝Consuming foods with a high water content more effectively reduced subsequent energy intake than did drinking water with food.❞

You can read the study in full (it’s a worthwhile read!) here:

Water incorporated into a food but not served with a food decreases energy intake in lean women

Protein matters

With all those fruits and vegetables and water, you may be wondering Dr. Rolls’ stance on proteins. It’s simple: protein is an appetite suppressant.

However, it takes about 20 minutes to signal the brain about that, so having some protein in a starter (if like this writer, you’re the cook of the household, a great option is to enjoy a small portion of nuts while cooking!) gets that clock ticking, to signal satiety sooner.

It may also help in other ways:

Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss

As for other foods that can suppress appetite, by the way, you might like;

25 Foods That Act As Natural Appetite Suppressants

Variety matters, and in ways other than you might think

A wide variety of foods (especially: a wide variety of plants) in one’s diet is well recognized as a key to a good balanced diet.

However…

A wide variety of dishes at the table, meanwhile, promotes greater consumption of food.

Dr. Rolls did a study on this too, a while ago now (you’ll see how old it is) but the science seems robust:

Variety in a Meal Enhances Food Intake in Man

Notwithstanding the title, it wasnot about a man (that was just how scientists wrote in ye ancient times of 1981). The test subjects were, in order: rats, cats, a mixed group of men and women, the same group again, and then a different group of all women.

So, Dr. Rolls’ advice is: it’s better to have one 20-ingredient dish, than 10 dishes with 20 ingredients between them.

Sorry! We love tapas and buffets too, but that’s the science!

So, “one-pot” meals are king in this regard; even if you serve it with one side (reasonable), that’s still only two dishes, which is pretty good going.

Note that the most delicious many-ingredient stir-fries and similar dishes from around the world also fall into this category!

Want to know more?

If you have the time (it’s an hour), you can enjoy a class of hers for free:

Want to watch it, but not right now? Bookmark it for later

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

How Beneficial Is MCT Oil, Really?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Often derived from coconuts (though it doesn’t have to be), medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) are trendy… But does the science back the hype?

First, the principle

MCTs are commonly enjoyed because unlike short- or long-chain fatty acids, they can be quickly broken down and either immediately converted quickly and easily into energy, or turned into ketones in the case of a surplus (in the case of true excess, however, it’ll simply be stored as fat).

Most of that involves the liver, so for anyone who wants a refresher on liver health:

How To Unfatty A Fatty Liver ← notwithstanding the title, this is also important knowledge even if your liver is healthy now—if you’d like it to stay healthy, anyway!

You can also read about the ins and outs of glycogen metabolism and the body’s energy-based metabolic processes in general (including the body’s energy processes that go on in the liver), here:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

If the liver turns the MCTs into ketones, those ketones will then be used for energy if there is insufficient glucose available (as the body will always use glucose from the blood first, if available, before moving to alternative energy sources such as ketones and/or fat reserves.)

Thus, many people look to ketones as a solution for having enough energy to function while on a very low-carb diet such as the ketogenic diet:

Ketogenic Diet: Burning Fat Or Burning Out?

…which as you’ll recall, does work for short-term weight loss, but brings long-term health risks, so should not be undertaken for long periods of time.

So, does MCT Oil help?

With regard to weight loss, the research is weak and mixed:

- Weak, because often the methodology was shoddy, often there are many factors not controlled-for, and often the sample sizes were small (and also, RCTs by their very nature tend to be quite short-term (often 6, 8, or 12 weeks), whereas heavy reliance on ketones from MCTs may fall into the same long-term problems as the ketogenic diet in general).

- Mixed, because the results varied widely (probably because of the aforementioned problems).

Rather than pick at individual studies, let’s look at this review and meta-analysis of 13 studies, with a combined sample size of 749 people (so you can imagine how small the individual RCTs were):

❝Compared with LCTs, MCTs decreased body weight (-0.51 kg [95% CI-0.80 to -0.23 kg]; P<0.001; I(2)=35%); waist circumference (-1.46 cm [95% CI -2.04 to -0.87 cm]; P<0.001; I(2)=0%), hip circumference (-0.79 cm [95% CI -1.27 to -0.30 cm]; P=0.002; I(2)=0%), total body fat (standard mean difference -0.39 [95% CI -0.57 to -0.22]; P<0.001; I(2)=0%), total subcutaneous fat (standard mean difference -0.46 [95% CI -0.64 to -0.27]; P<0.001; I(2)=20%), and visceral fat (standard mean difference -0.55 [95% CI -0.75 to -0.34]; P<0.001; I(2)=0%).

No differences were seen in blood lipid levels.

Many trials lacked sufficient information for a complete quality assessment, and commercial bias was detected.❞

So, if we’re going to take those numbers at face value, that means a net weight loss, over the course of the trial period, was…

*drumroll*

0.51kg (that’s about 1 lb).

To put that into perspective, if you did nothing else but pee 1 cup of urine before getting weighed, you’d register as having lost 0.25kg (or about ½ lb) by virtue of the bathroom trip alone.

Here’s the paper:

What about cholesterol and heart health?

With regard to cholesterol, MCT oil is touted as improving blood lipids, which means lowering LDL and increasing HDL (within a safe range, anyway).

You’ll remember that the above review concluded “No differences were seen in blood lipid levels”.

It may again be a case of individual studies cancelling each other out. For example…

This study found that it improved lipids in 40 young women as part of a calorie-controlled interventional diet:

This study found that it worsened lipids in 17 young men, worse even than taking an equivalent amount of sunflower oil:

In short, it’s a gamble.

It may be good for insulin sensitivity, though

This one seems to be specific to people with type 2 diabetes. The paper heading says it all, but we include the link in case you want to know the details (the short version is, it improved insulin sensitivity in diabetic subjects only (not others), and didn’t affect anything else that was measured:

The sample size was small (20 people total, of whom 10 had diabetes), and the next study was with 40 people, this time moderately overweight and all with type 2 diabetes:

Want to try some?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon 😎

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

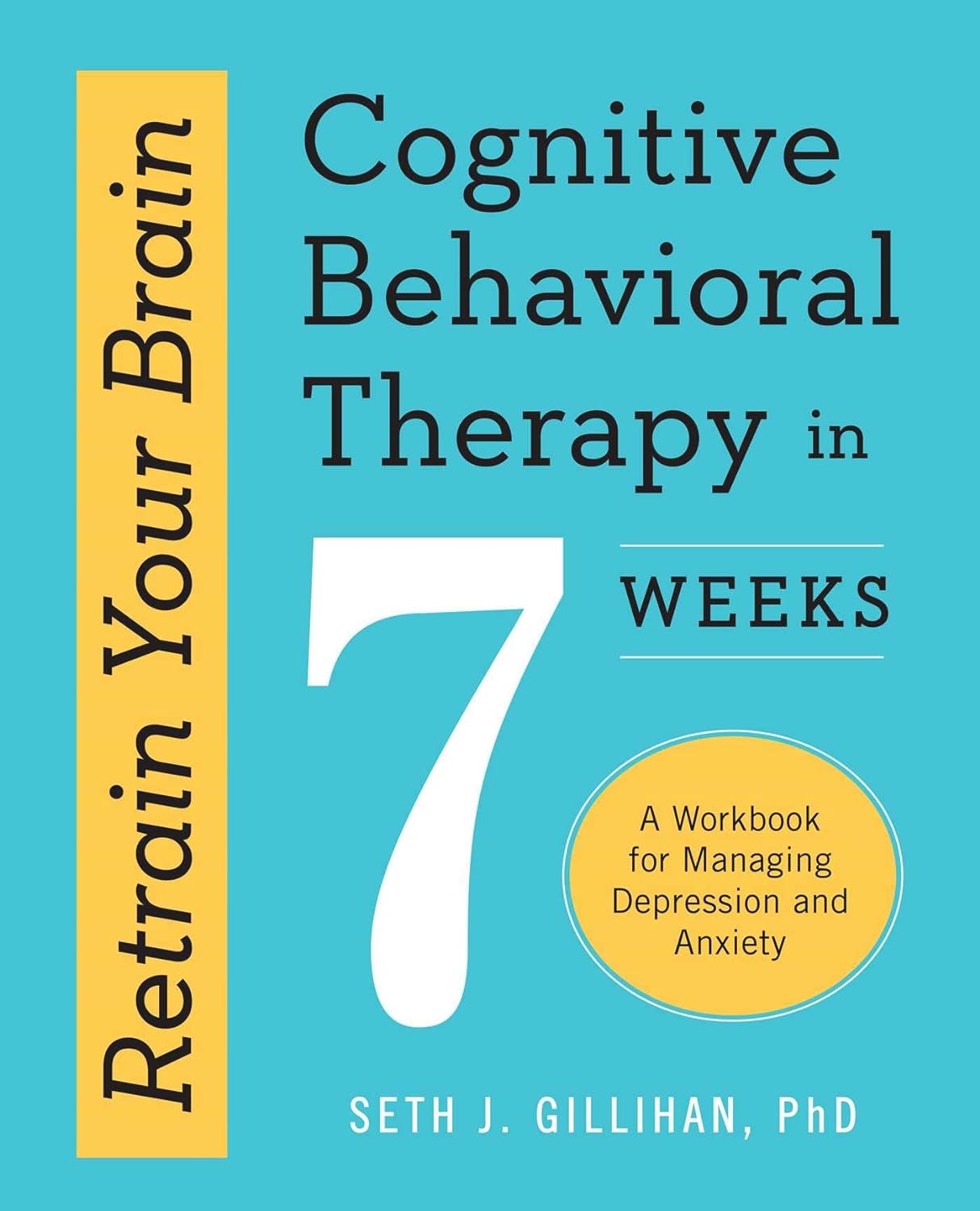

Retrain Your Brain – by Dr. Seth Gillihan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

15-Minute Arabic”, “Sharpen Your Chess Tactics in 24 Hours”, “Change Your Life in 7 Days”, “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 weeks”—all real books from this reviewer’s shelves.

The thing with books with these sorts of time periods in the titles is that the time period in the title often bears little relation to how long it takes to get through the book. So what’s the case here?

You’ll probably get through it in more like 7 days, but the pacing is more important than the pace. By that we mean:

Dr. Gillihan starts by assuming the reader is at best “in a rut”, and needs to first pick a direction to head in (the first “week”) and then start getting one’s life on track (the second “week”).

He then gives us, one by one, an array of tools and power-ups to do increasingly better. These tools aren’t just CBT, though of course that features prominently. There’s also mindfulness exercises, and holistic / somatic therapy too, for a real “bringing it all together” feel.

And that’s where this book excels—at no point is the reader left adrift with potential stumbling-blocks left unexamined. It’s a “whole course”.

Bottom line: whether it takes you 7 hours or 7 months, “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 Weeks” is a CBT-and-more course for people who like courses to work through. It’ll get you where you’re going… Wherever you want that to be for you!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

5 Things To Know About Passive Suicidal Ideation

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you’ve ever wanted to go to sleep and never wake up, or have some accident/incident/illness take you with no action on your part, or a loved one has ever expressed such thoughts/feelings to you… Then this video is for you. Dr. Scott Eilers explains:

Tired of living

We’ll not keep them a mystery; here are the five things that Dr. Eilers wants us to know about passive suicidal ideation:

- What it is: a desire for something to end your life without taking active steps. While it may seem all too common, it’s not necessarily inevitable or unchangeable.

- What it means in terms of severity: it isn’t a clear indicator of how severe someone’s depression is. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the person’s depression is mild; it can be severe even without active suicidal thoughts, or indeed, suicidality at all.

- What it threatens: although passive suicidal ideation doesn’t usually involve active planning, it can still be dangerous. Over time, it can evolve into active suicidal ideation or lead to risky behaviors.

- What it isn’t: passive suicidal ideation is different from intrusive thoughts, which are unwanted, distressing thoughts about death. The former involves a desire for death, while the latter does not.

- What it doesn’t have to be: passive suicidal ideation is often a symptom of underlying depression or a mood disorder, which can be treated through therapy, medication, or a combination of both. Seeking treatment is crucial and can be life-changing.

For more on all of the above, here’s Dr. Eilers with his own words:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- The Mental Health First Aid You’ll Hopefully Never Need ← about depression generally

- How To Stay Alive (When You Really Don’t Want To) ← about suicidality specifically

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Will there soon be a cure for HIV?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is a chronic health condition that can be fatal without treatment. People with HIV can live healthy lives by taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), but this medication must be taken daily in order to work, and treatment can be costly. Fortunately, researchers believe a cure is possible.

In July, a seventh person was reportedly cured of HIV following a 2015 stem cell transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. The patient stopped taking ART in 2018 and has remained in remission from HIV.

Read on to learn more about HIV, the promise of stem cell transplants, and what other potential cures are on the horizon.

What is HIV?

HIV infects and destroys the immune system’s cells, making people more susceptible to infections. If left untreated, HIV will severely impair the immune system and progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). People living with untreated AIDS typically die within three years.

People with HIV can take ART to help their immune systems recover and to reduce their viral load to an undetectable level, which slows the progression of the disease and prevents them passing the virus to others.

How can stem cell transplants cure HIV?

Several people have been cured of HIV after receiving stem cell transplants to treat leukemia or lymphoma. Stem cells are produced by the spongy tissue located in the center of some bones, and they can turn into new blood cells.

A mutation on the CCR5 gene prevents HIV from infecting new cells and creates resistance to the virus, which is why some HIV-positive people have received stem cells from donors carrying this mutation. (One person was reportedly cured of HIV after receiving stem cells without the CCR5 mutation, but further research is needed to understand how this occurred.)

Despite this promising news, experts warn that stem cell transplants can be fatal, so it’s unlikely this treatment will be available to treat people with HIV unless a stem cell transplant is needed to treat cancer. People with HIV are at an increased risk for blood cancers, such as Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which stem cell transplants can treat.

Additionally, finding compatible donors with the CCR5 mutation who share genetic heritage with patients of color can be challenging, as donors with the mutation are typically white.

What are other potential cures for HIV?

In some rare cases, people who started ART shortly after infection and later stopped treatment have maintained undetectable levels of HIV in their bodies. There have also been some people whose bodies have been able to maintain low viral loads without any ART at all.

Researchers are studying these cases in their search for a cure.

Other treatment options researchers are exploring include:

- Gene therapy: In addition to stem cell transplants, gene therapy for HIV involves removing genes from HIV particles in patients’ bodies to prevent the virus from infecting other cells.

- Immunotherapy: This treatment is typically used in cancer patients to teach their immune systems how to fight off cancer. Research has shown that giving some HIV patients antibodies that target the virus helps them reach undetectable levels of HIV without ART.

- mRNA technology: mRNA, a type of genetic material that helps produce proteins, has been used in vaccines to teach cells how to fight off viruses. Researchers are seeking a way to send mRNA to immune system cells that contain HIV.

When will there be a cure for HIV?

The United Nations and several countries have pledged to end HIV and AIDS by 2030, and a 2023 UNAIDS report affirmed that reaching this goal is possible. However, strategies to meet this goal include HIV prevention and improving access to existing treatment alongside the search for a cure, so we still don’t know when a cure might be available.

How can I find out if I have HIV?

You can get tested for HIV from your primary care provider or at your local health center. You can also purchase an at-home HIV test from a drugstore or online. If your at-home test result is positive, follow up with your health care provider to confirm the diagnosis and get treatment.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: