What’s the difference between Alzheimer’s and dementia?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

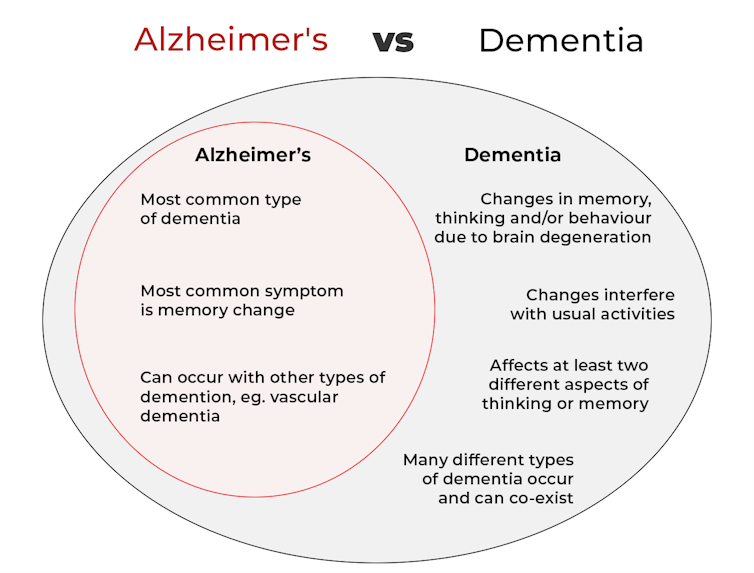

Changes in thinking and memory as we age can occur for a variety of reasons. These changes are not always cause for concern. But when they begin to disrupt daily life, it could indicate the first signs of dementia.

Another term that can crop up when we’re talking about dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, or Alzheimer’s for short.

So what’s the difference?

What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a range of syndromes that result in changes in memory, thinking and/or behaviour due to degeneration in the brain.

To meet the criteria for dementia these changes must be sufficiently pronounced to interfere with usual activities and are present in at least two different aspects of thinking or memory.

For example, someone might have trouble remembering to pay bills and become lost in previously familiar areas.

It’s less-well known that dementia can also occur in children. This is due to progressive brain damage associated with more than 100 rare genetic disorders. This can result in similar cognitive changes as we see in adults.

So what’s Alzheimer’s then?

Alzheimer’s is the most common type of dementia, accounting for about 60-80% of cases.

So it’s not surprising many people use the terms dementia and Alzheimer’s interchangeably.

Changes in memory are the most common sign of Alzheimer’s and it’s what the public most often associates with it. For instance, someone with Alzheimer’s may have trouble recalling recent events or keeping track of what day or month it is.

We still don’t know exactly what causes Alzheimer’s. However, we do know it is associated with a build-up in the brain of two types of protein called amyloid-β and tau.

While we all have some amyloid-β, when too much builds up in the brain it clumps together, forming plaques in the spaces between cells. These plaques cause damage (inflammation) to surrounding brain cells and leads to disruption in tau. Tau forms part of the structure of brain cells but in Alzheimer’s tau proteins become “tangled”. This is toxic to the cells, causing them to die. A feedback loop is then thought to occur, triggering production of more amyloid-β and more abnormal tau, perpetuating damage to brain cells.

Alzheimer’s can also occur with other forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia. This combination is the most common example of a mixed dementia.

Vascular dementia

The second most common type of dementia is vascular dementia. This results from disrupted blood flow to the brain.

Because the changes in blood flow can occur throughout the brain, signs of vascular dementia can be more varied than the memory changes typically seen in Alzheimer’s.

For example, vascular dementia may present as general confusion, slowed thinking, or difficulty organising thoughts and actions.

Your risk of vascular dementia is greater if you have heart disease or high blood pressure.

Frontotemporal dementia

Some people may not realise that dementia can also affect behaviour and/or language. We see this in different forms of frontotemporal dementia.

The behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia is the second most common form (after Alzheimer’s disease) of younger onset dementia (dementia in people under 65).

People living with this may have difficulties in interpreting and appropriately responding to social situations. For example, they may make uncharacteristically rude or offensive comments or invade people’s personal space.

Semantic dementia is also a type of frontotemporal dementia and results in difficulty with understanding the meaning of words and naming everyday objects.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies results from dysregulation of a different type of protein known as α-synuclein. We often see this in people with Parkinson’s disease.

So people with this type of dementia may have altered movement, such as a stooped posture, shuffling walk, and changes in handwriting. Other symptoms include changes in alertness, visual hallucinations and significant disruption to sleep.

Do I have dementia and if so, which type?

If you or someone close to you is concerned, the first thing to do is to speak to your GP. They will likely ask you some questions about your medical history and what changes you have noticed.

Sometimes it might not be clear if you have dementia when you first speak to your doctor. They may suggest you watch for changes or they may refer you to a specialist for further tests.

There is no single test to clearly show if you have dementia, or the type of dementia. A diagnosis comes after multiple tests, including brain scans, tests of memory and thinking, and consideration of how these changes impact your daily life.

Not knowing what is happening can be a challenging time so it is important to speak to someone about how you are feeling or to reach out to support services.

Dementia is diverse

As well as the different forms of dementia, everyone experiences dementia in different ways. For example, the speed dementia progresses varies a lot from person to person. Some people will continue to live well with dementia for some time while others may decline more quickly.

There is still significant stigma surrounding dementia. So by learning more about the various types of dementia and understanding differences in how dementia progresses we can all do our part to create a more dementia-friendly community.

The National Dementia Helpline (1800 100 500) provides information and support for people living with dementia and their carers. To learn more about dementia, you can take this free online course.

Nikki-Anne Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How a Friend’s Death Turned Colorado Teens Into Anti-Overdose Activists

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gavinn McKinney loved Nike shoes, fireworks, and sushi. He was studying Potawatomi, one of the languages of his Native American heritage. He loved holding his niece and smelling her baby smell. On his 15th birthday, the Durango, Colorado, teen spent a cold December afternoon chopping wood to help neighbors who couldn’t afford to heat their homes.

McKinney almost made it to his 16th birthday. He died of fentanyl poisoning at a friend’s house in December 2021. His friends say it was the first time he tried hard drugs. The memorial service was so packed people had to stand outside the funeral home.

Now, his peers are trying to cement their friend’s legacy in state law. They recently testified to state lawmakers in support of a bill they helped write to ensure students can carry naloxone with them at all times without fear of discipline or confiscation. School districts tend to have strict medication policies. Without special permission, Colorado students can’t even carry their own emergency medications, such as an inhaler, and they are not allowed to share them with others.

“We realized we could actually make a change if we put our hearts to it,” said Niko Peterson, a senior at Animas High School in Durango and one of McKinney’s friends who helped write the bill. “Being proactive versus being reactive is going to be the best possible solution.”

Individual school districts or counties in California, Maryland, and elsewhere have rules expressly allowing high school students to carry naloxone. But Jon Woodruff, managing attorney at the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association, said he wasn’t aware of any statewide law such as the one Colorado is considering. Woodruff’s Washington, D.C.-based organization researches and drafts legislation on substance use.

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that can halt an overdose. Available over the counter as a nasal spray, it is considered the fire extinguisher of the opioid epidemic, for use in an emergency, but just one tool in a prevention strategy. (People often refer to it as “Narcan,” one of the more recognizable brand names, similar to how tissues, regardless of brand, are often called “Kleenex.”)

The Biden administration last year backed an ad campaign encouraging young people to carry the emergency medication.

Most states’ naloxone access laws protect do-gooders, including youth, from liability if they accidentally harm someone while administering naloxone. But without school policies explicitly allowing it, the students’ ability to bring naloxone to class falls into a gray area.

Ryan Christoff said that in September 2022 fellow staff at Centaurus High School in Lafayette, Colorado, where he worked and which one of his daughters attended at the time, confiscated naloxone from one of her classmates.

“She didn’t have anything on her other than the Narcan, and they took it away from her,” said Christoff, who had provided the confiscated Narcan to that student and many others after his daughter nearly died from fentanyl poisoning. “We should want every student to carry it.”

Boulder Valley School District spokesperson Randy Barber said the incident “was a one-off and we’ve done some work since to make sure nurses are aware.” The district now encourages everyone to consider carrying naloxone, he said.

Community’s Devastation Turns to Action

In Durango, McKinney’s death hit the community hard. McKinney’s friends and family said he didn’t do hard drugs. The substance he was hooked on was Tapatío hot sauce — he even brought some in his pocket to a Rockies game.

After McKinney died, people started getting tattoos of the phrase he was known for, which was emblazoned on his favorite sweatshirt: “Love is the cure.” Even a few of his teachers got them. But it was classmates, along with their friends at another high school in town, who turned his loss into a political movement.

“We’re making things happen on behalf of him,” Peterson said.

The mortality rate has spiked in recent years, with more than 1,500 other children and teens in the U.S. dying of fentanyl poisoning the same year as McKinney. Most youth who die of overdoses have no known history of taking opioids, and many of them likely thought they were taking prescription opioids like OxyContin or Percocet — not the fake prescription pills that increasingly carry a lethal dose of fentanyl.

“Most likely the largest group of teens that are dying are really teens that are experimenting, as opposed to teens that have a long-standing opioid use disorder,” said Joseph Friedman, a substance use researcher at UCLA who would like to see schools provide accurate drug education about counterfeit pills, such as with Stanford’s Safety First curriculum.

Allowing students to carry a low-risk, lifesaving drug with them is in many ways the minimum schools can do, he said.

“I would argue that what the schools should be doing is identifying high-risk teens and giving them the Narcan to take home with them and teaching them why it matters,” Friedman said.

Writing in The New England Journal of Medicine, Friedman identified Colorado as a hot spot for high school-aged adolescent overdose deaths, with a mortality rate more than double that of the nation from 2020 to 2022.

“Increasingly, fentanyl is being sold in pill form, and it’s happening to the largest degree in the West,” said Friedman. “I think that the teen overdose crisis is a direct result of that.”

If Colorado lawmakers approve the bill, “I think that’s a really important step,” said Ju Nyeong Park, an assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, who leads a research group focused on how to prevent overdoses. “I hope that the Colorado Legislature does and that other states follow as well.”

Park said comprehensive programs to test drugs for dangerous contaminants, better access to evidence-based treatment for adolescents who develop a substance use disorder, and promotion of harm reduction tools are also important. “For example, there is a national hotline called Never Use Alone that anyone can call anonymously to be supervised remotely in case of an emergency,” she said.

Taking Matters Into Their Own Hands

Many Colorado school districts are training staff how to administer naloxone and are stocking it on school grounds through a program that allows them to acquire it from the state at little to no cost. But it was clear to Peterson and other area high schoolers that having naloxone at school isn’t enough, especially in rural places.

“The teachers who are trained to use Narcan will not be at the parties where the students will be using the drugs,” he said.

And it isn’t enough to expect teens to keep it at home.

“It’s not going to be helpful if it’s in somebody’s house 20 minutes outside of town. It’s going to be helpful if it’s in their backpack always,” said Zoe Ramsey, another of McKinney’s friends and a senior at Animas High School.

“We were informed it was against the rules to carry naloxone, and especially to distribute it,” said Ilias “Leo” Stritikus, who graduated from Durango High School last year.

But students in the area, and their school administrators, were uncertain: Could students get in trouble for carrying the opioid antagonist in their backpacks, or if they distributed it to friends? And could a school or district be held liable if something went wrong?

He, along with Ramsey and Peterson, helped form the group Students Against Overdose. Together, they convinced Animas, which is a charter school, and the surrounding school district, to change policies. Now, with parental permission, and after going through training on how to administer it, students may carry naloxone on school grounds.

Durango School District 9-R spokesperson Karla Sluis said at least 45 students have completed the training.

School districts in other parts of the nation have also determined it’s important to clarify students’ ability to carry naloxone.

“We want to be a part of saving lives,” said Smita Malhotra, chief medical director for Los Angeles Unified School District in California.

Los Angeles County had one of the nation’s highest adolescent overdose death tallies of any U.S. county: From 2020 to 2022, 111 teens ages 14 to 18 died. One of them was a 15-year-old who died in a school bathroom of fentanyl poisoning. Malhotra’s district has since updated its policy on naloxone to permit students to carry and administer it.

“All students can carry naloxone in our school campuses without facing any discipline,” Malhotra said. She said the district is also doubling down on peer support and hosting educational sessions for families and students.

Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland took a similar approach. School staff had to administer naloxone 18 times over the course of a school year, and five students died over the course of about one semester.

When the district held community forums on the issue, Patricia Kapunan, the district’s medical officer, said, “Students were very vocal about wanting access to naloxone. A student is very unlikely to carry something in their backpack which they think they might get in trouble for.”

So it, too, clarified its policy. While that was underway, local news reported that high school students found a teen passed out, with purple lips, in the bathroom of a McDonald’s down the street from their school, and used Narcan to revive them. It was during lunch on a school day.

“We can’t Narcan our way out of the opioid use crisis,” said Kapunan. “But it was critical to do it first. Just like knowing 911.”

Now, with the support of the district and county health department, students are training other students how to administer naloxone. Jackson Taylor, one of the student trainers, estimated they trained about 200 students over the course of three hours on a recent Saturday.

“It felt amazing, this footstep toward fixing the issue,” Taylor said.

Each trainee left with two doses of naloxone.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

-

Mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem. What should we call mental distress?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We talk about mental health more than ever, but the language we should use remains a vexed issue.

Should we call people who seek help patients, clients or consumers? Should we use “person-first” expressions such as person with autism or “identity-first” expressions like autistic person? Should we apply or avoid diagnostic labels?

These questions often stir up strong feelings. Some people feel that patient implies being passive and subordinate. Others think consumer is too transactional, as if seeking help is like buying a new refrigerator.

Advocates of person-first language argue people shouldn’t be defined by their conditions. Proponents of identity-first language counter that these conditions can be sources of meaning and belonging.

Avid users of diagnostic terms see them as useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can box people in and misrepresent their problems as pathologies.

Underlying many of these disagreements are concerns about stigma and the medicalisation of suffering. Ideally the language we use should not cast people who experience distress as defective or shameful, or frame everyday problems of living in psychiatric terms.

Our new research, published in the journal PLOS Mental Health, examines how the language of distress has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here’s what we found.

Engin Akyurt/Pexels Generic terms for the class of conditions

Generic terms – such as mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem – have largely escaped attention in debates about the language of mental ill health. These terms refer to mental health conditions as a class.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include mental, mental health, psychiatric and psychological, and common nouns include condition, disease, disorder, disturbance, illness, and problem. Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ in their connotations. Disease and illness sound the most medical, whereas condition, disturbance and problem need not relate to health. Mental implies a direct contrast with physical, whereas psychiatric implicates a medical specialty.

Mental health problem, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathologising. It implies that something is to be solved rather than treated, makes no direct reference to medicine, and carries the positive connotations of health rather than the negative connotation of illness or disease.

Is ‘mental health problem’ actually less pathologising? Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock Arguably, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls the “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency for language to evolve new terms to escape (at least temporarily) the offensive connotations of those they replace.

English linguist Hazel Price argues that mental health has increasingly come to replace mental illness to avoid the stigma associated with that term.

How has usage changed over time?

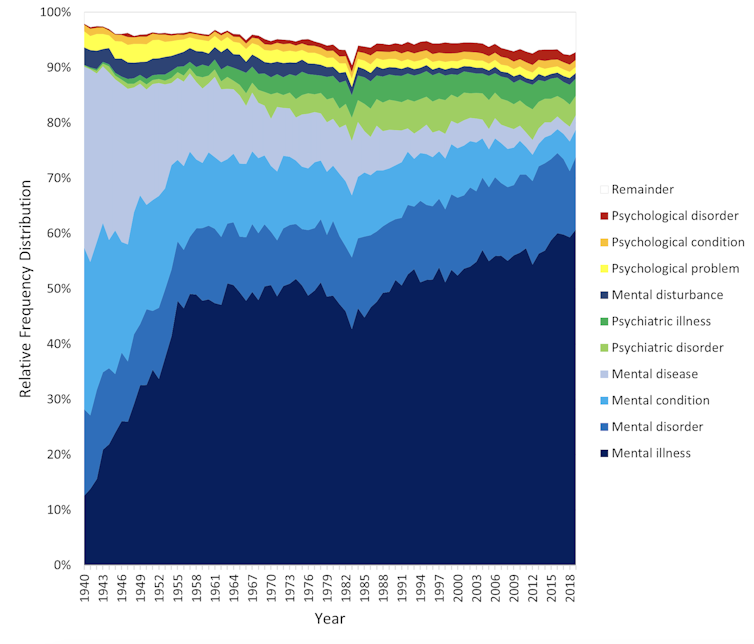

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the popularity of 24 generic terms: every combination of the nouns and adjectives listed above.

We explore the frequency with which each term appears from 1940 to 2019 in two massive text data sets representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The findings are very similar in both data sets.

The figure presents the relative popularity of the top ten terms in the larger data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined into the remainder.

Relative popularity of alternative generic terms in the Google Books corpus. Haslam et al., 2024, PLOS Mental Health. Several trends appear. Mental has consistently been the most popular adjective component of the generic terms. Mental health has become more popular in recent years but is still rarely used.

Among nouns, disease has become less widely used while illness has become dominant. Although disorder is the official term in psychiatric classifications, it has not been broadly adopted in public discourse.

Since 1940, mental illness has clearly become the preferred generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, it has steadily risen in popularity.

Does it matter?

Our study documents striking shifts in the popularity of generic terms, but do these changes matter? The answer may be: not much.

One study found people think mental disorder, mental illness and mental health problem refer to essentially identical phenomena.

Other studies indicate that labelling a person as having a mental disease, mental disorder, mental health problem, mental illness or psychological disorder makes no difference to people’s attitudes toward them.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, but the evidence to date suggests they are minimal.

The labels we use may not have a big impact on levels of stigma. Pixabay/Pexels Is ‘distress’ any better?

Recently, some writers have promoted distress as an alternative to traditional generic terms. It lacks medical connotations and emphasises the person’s subjective experience rather than whether they fit an official diagnosis.

Distress appears 65 times in the 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing Act, usually in the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By implication, distress is a broad concept akin to but not synonymous with mental ill health.

But is distress destigmatising, as it was intended to be? Apparently not. According to one study, it was more stigmatising than its alternatives. The term may turn us away from other people’s suffering by amplifying it.

So what should we call it?

Mental illness is easily the most popular generic term and its popularity has been rising. Research indicates different terms have little or no effect on stigma and some terms intended to destigmatise may backfire.

We suggest that mental illness should be embraced and the proliferation of alternative terms such as mental health problem, which breed confusion, should end.

Critics might argue mental illness imposes a medical frame. Philosopher Zsuzsanna Chappell disagrees. Illness, she argues, refers to subjective first-person experience, not to an objective, third-person pathology, like disease.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centres the individual and their connections. “When I identify my suffering as illness-like,” Chappell writes, “I wish to lay claim to a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As generic terms go, mental illness is a healthy option.

Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne and Naomi Baes, Researcher – Social Psychology/ Natural Language Processing, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

How To Get More Nutrition From The Same Food

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How To Get More Out Of What’s On Your Plate

Where does digestion begin? It’s not the stomach. It’s not even the mouth.

It’s when we see and smell our food; maybe even hear it! “Sell the sizzle, not the steak” has a biological underpinning.

At that point, when we begin to salivate, that’s just one of many ways that our body is preparing itself for what we’re about to receive.

When we grab some ready-meal and wolf it down, we undercut that process. In the case of ready-meals, they often didn’t have much nutritional value, but even the most nutritious food isn’t going to do us nearly as much good if it barely touches the sides on the way down.

We’re not kidding about the importance of that initial stage of our external senses, by the way:

- Food perception primes hepatic endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis via melanocortin-dependent control of mTOR activation

- Olfaction regulates organismal proteostasis and longevity via microRNA-dependent signalling

So, mindful eating is not just something for Instagrammable “what I eat in a day” aesthetic photos, nor is just for monks atop cold mountains. There is actual science here, and a lot of it.

It starts with ingredients

“Eating the rainbow” (no, Skittles do not count) is great health advice for getting a wide variety of micronutrients, but it’s also simply beneficial for our senses, too. Which, as above-linked, makes a difference to digestion and nutrient absorption.

Enough is enough

That phrase always sounds like an expression of frustration, “Enough is enough!”. But, really:

Don’t overcomplicate your cooking, especially if you’re new to this approach. You can add in more complexities later, but for now, figure out what will be “enough”, and let it be enough.

The kitchen flow

Here we’re talking about flow in the Csikszentmihalyi sense of the word. Get “into the swing of things” and enjoy your time in the kitchen. Schedule more time than you need, and take it casually. Listen to your favourite music. Dance while you cook. Taste things as you go.

There are benefits, by the way, not just to our digestion (in being thusly primed and prepared for eating), but also to our cognition:

In The Zone: Flow State and Cognition in Older Adults

Serve

No, not just “put the food on the table”, but serve.

Have a pleasant environment; with sensory pleasures but without too many sensory distractions. Think less “the news on in the background” and more smooth jazz or Mozart or whatever works for you. Use your favourite (small!) plates/bowls, silverware, glasses. Have a candle if you like (unscented!).

Pay attention to presentation on the plate / in the bowl / in any “serve yourself” serving-things. Use a garnish (parsley is great if you want to add a touch of greenery without changing the flavor much). Crack that black pepper at the table. Make any condiments count (less “ketchup bottle” and more “elegant dip”).

Take your time

Say grace if that fits with your religious traditions, and/or take a moment to reflect on gratitude.

In many languages there’s a pre-dinner blessing that most often translates to “good appetite”. This writer is fond of the Norwegian “Velbekommen”, and it means more like “May good come of it for you”, or “May it do you good”.

Then, enjoy the food.

For the most even of blood sugar levels, consider eating fiber, protein/fat, carbs, in that order.

Why? See: 10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars

Chew adequately and mindfully. Put your fork (or spoon, or chopsticks, or whatever) down between bites. Drink water alongside your meal.

Try to take at least 20 minutes to enjoy your meal, and/but any time you go to reach for another helping, take a moment to check in with yourself with regard to whether you are actually still hungry. If you’re not, and are just eating for pleasure, consider deferring that pleasure by saving the food for later.

At this point, people with partners/family may be thinking “But it won’t be there later! Someone else will eat it!”, and… That’s fine! Be happy for them. You can cook again tomorrow. You prepared delicious wholesome food that your partner/family enjoyed, and that’s always a good thing.

Want to know more about the science of mindful eating?

Check out Harvard’s Dr. Lilian Cheung on Mindful Eating here!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How White Is Your Tongue?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝So its normal to develop a white sort of coating on the tongue, right? It develops when I eat, and is able to (somewhat) easily be brushed off❞

If (and only if) there is no soreness and the coverage of the whiteness is not extreme, then, yes, that is normal and fine.

Your mouth has a microbiome, and it’s supposed to have one (helps keep the conditions in your mouth correct, so that food is broken down and/but your gums and teeth aren’t).

Read more: The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease

The whiteness you often see on a healthy tongue is, for the most part, bacteria and dead cells—harmless.

Cleaning the whiteness off with your brush is fine. You can also scrape off with floss is similar if you prefer. Or a tongue-scraper! Those can be especially good for people for whom brushing the tongue is an unpleasant sensation. Or you can just leave it, if it doesn’t bother you.

By the way, that microbiome is a reason it can be good to go easy on the mouthwash. Moderate use of mouthwash is usually fine, but you don’t want to wipe out your microbiome then have it taken over by unpleasantries that the mouthwash didn’t kill (unpleasantries like C. albicans).

There are other mouthwash-related considerations too:

Toothpastes and mouthwashes: which kinds help, and which kinds harm?

If you start to get soreness, that probably means the papillae (little villi-like things) are inflamed. If there is soreness, and/or the whiteness is extreme, then it could be a fungal infection (usually C. albicans, also called Thrush), in which case, antifungal medications will be needed, which you can probably get over the counter from your pharmacist.

Do not try to self-treat with antibiotics.

Antibiotics will make a fungal infection worse (indeed, antibiotic usage is often the reason for getting fungal growth in the first place) by wiping out the bacteria that normally keep it in check.

Other risk factors include a sugary diet, smoking, and medications that have “dry mouth” as a side effect.

Read more: Can oral thrush be prevented?

If you have any symptoms more exciting than the above, then definitely see a doctor.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Blue Zones Kitchen – by Dan Buettner

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Buettner’s other book, The Blue Zones: 9 Lessons For Living Longer From The People Who’ve Lived The Longest, and with this one, it’s now time to focus on the dietary aspect.

As the title and subtitle promises, we get 100 recipes, inspired by Blue Zone cuisines. The recipes themselves have been tweaked a little for maximum healthiness, eliminating some ingredients that do crop up in the Blue Zones but are exceptions to their higher average healthiness rather than the rule.

The recipes are arranged by geographic zone rather than by meal type, so it might take a full read-through before knowing where to find everything, but it makes it a very enjoyable “coffee-table book” to browse, as well as being practical in the kitchen. The ingredients are mostly easy to find globally, and most can be acquired at a large supermarket and/or health food store. In the case of substitutions, most are obvious, e.g. if you don’t have wild fennel where you are, use cultivated, for example.

In the category of criticism, it appears that Buettner is very unfamiliar with spices, and so has skipped them almost entirely. We at 10almonds could never skip them, and heartily recommend adding your own spices, for their health benefits and flavors. It may take a little experimentation to know what will work with what recipes, but if you’re accustomed to cooking with spices normally, it’s unlikely that you’ll err by going with your heart here.

Bottom line: we’d give this book a once-over for spice additions, but aside from that, it’s a fine book of cuisine-by-location cooking.

Click here to check out The Blue Zones Kitchen, and get cooking into your own three digits!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can you ‘boost’ your immune system?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As flu season and a likely winter COVID-19 wave approach, you may encounter both proven and unproven methods claiming to “boost” your immune system. Before you reach for supplements, learn more about how the immune system works, how vaccines give us the best protection against many illnesses, and how some lifestyle factors can help your immune system function properly.

What is the immune system?

The immune system is the body’s first line of defense against invaders like viruses, bacteria, or fungi. You develop immunity—or protection from infection—when your immune system has learned how to recognize an invader and attack it before it makes you sick.

How can you boost your immune system?

You can teach your immune system how to fight back against dangerous invaders by staying up to date on vaccines. This season’s updated flu and COVID-19 vaccines target newer variants and are recommended for everyone 6 months and older.

Vaccines reduce your risk of getting sick and spreading illness to others. Even if you get infected with a disease after you’ve been vaccinated against it, the vaccine will still increase protection against severe illness, hospitalization, and death.

People who have compromised immune systems due to certain health conditions or because they need to take immunosuppressant medications may need additional vaccine doses.

Find out which vaccines you and your children need by using the CDC’s Adult Vaccine Assessment Tool and Child and Adolescent Vaccine Assessment Tool. Talk to your health care provider about the best vaccines for your family.

Find pharmacies offering updated flu and COVID-19 vaccines by visiting Vaccines.gov.

Can supplements boost your immune system?

Many vitamin, mineral, and herbal supplements that are marketed as “immune boosting” have little to no effect on your immune system. Research is split on whether some of these supplements—like vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc—are capable of helping your body fight infections.

Plus, the Food and Drug Administration typically does not review supplements until after they have reached store shelves, and companies can sell supplements without notifying the FDA. This means that supplements may not be accurately labeled.

Eating a diverse diet rich in fruits and vegetables is the best way for most people to absorb nutrients that support optimal immune system function. People with certain health conditions and deficiencies may need specific supplements prescribed by a health care provider. For example, people with anemia may need iron supplements in order to maintain appropriate iron levels.

Before you begin taking a new supplement, talk to your health care provider, as some supplements may interact with medications you are taking or worsen certain health conditions.

Can lifestyle factors strengthen your immune system?

Based on current evidence, there is no direct link between lifestyle changes and enhanced immunity to infections. However, maintaining a healthy lifestyle through the following practices can help ensure that your immune system functions as it should:

- Eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables.

- Exercise regularly.

- Don’t smoke.

- Limit or eliminate alcohol consumption.

- Get seven or more hours of sleep per night.

- Reduce stress.

Taking steps to avoid contact with germs also reduces your risk of getting sick. Safer sex barriers like condoms protect against HIV, while wearing a high-quality, well-fitting mask—especially in high-risk environments—protects against COVID-19. Both of these illnesses can reduce your production of white blood cells, which protect against infection.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: