What is PMDD?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a mood disorder that causes significant mental health changes and physical symptoms leading up to each menstrual period.

Unlike premenstrual syndrome (PMS), which affects approximately three out of four menstruating people, only 3 percent to 8 percent of menstruating people have PMDD. However, some researchers believe the condition is underdiagnosed, as it was only recently recognized as a medical diagnosis by the World Health Organization.

Read on to learn more about its symptoms, the difference between PMS and PMDD, treatment options, and more.

What are the symptoms of PMDD?

People with PMDD typically experience both mood changes and physical symptoms during each menstrual cycle’s luteal phase—the time between ovulation and menstruation. These symptoms typically last seven to 14 days and resolve when menstruation begins.

Mood symptoms may include:

- Irritability

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Extreme or sudden mood shifts

- Difficulty concentrating

- Depression and suicidal ideation

Physical symptoms may include:

- Fatigue

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Changes in appetite

- Body aches

- Bloating

- Abdominal cramps

- Breast swelling or tenderness

What is the difference between PMS and PMDD?

Both PMS and PMDD cause emotional and physical symptoms before menstruation. Unlike PMS, PMDD causes extreme mood changes that disrupt daily life and may lead to conflict with friends, family, partners, and coworkers. Additionally, symptoms may last longer than PMS symptoms.

In severe cases, PMDD may lead to depression or suicide. More than 70 percent of people with the condition have actively thought about suicide, and 34 percent have attempted it.

What is the history of PMDD?

PMDD wasn’t added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 2013. In 2019, the World Health Organization officially recognized it as a medical diagnosis.

References to PMDD in medical literature date back to the 1960s, but defining it as a mental health and medical condition initially faced pushback from women’s rights groups. These groups were concerned that recognizing the condition could perpetuate stereotypes about women’s mental health and capabilities before and during menstruation.

Today, many women-led organizations are supportive of PMDD being an official diagnosis, as this has helped those living with the condition access care.

What causes PMDD?

Researchers don’t know exactly what causes PMDD. Many speculate that people with the condition have an abnormal response to fluctuations in hormones and serotonin—a brain chemical impacting mood— that occur throughout the menstrual cycle. Symptoms fully resolve after menopause.

People who have a family history of premenstrual symptoms and mood disorders or have a personal history of traumatic life events may be at higher risk of PMDD.

How is PMDD diagnosed?

Health care providers of many types, including mental health providers, can diagnose PMDD. Providers typically ask patients about their premenstrual symptoms and the amount of stress those symptoms are causing. Some providers may ask patients to track their periods and symptoms for one month or longer to determine whether those symptoms are linked to their menstrual cycle.

Some patients may struggle to receive a PMDD diagnosis, as some providers may lack knowledge about the condition. If your provider is unfamiliar with the condition and unwilling to explore treatment options, find a provider who can offer adequate support. The International Association for Premenstrual Disorders offers a directory of providers who treat the condition.

How is PMDD treated?

There is no cure for PMDD, but health care providers can prescribe medication to help manage symptoms. Some medication options include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants that regulate serotonin in the brain and may improve mood when taken daily or during the luteal phase of each menstrual cycle.

- Hormonal birth control to prevent ovulation-related hormonal changes.

- Over-the-counter pain medication like Tylenol, which can ease headaches, breast tenderness, abdominal cramping, and other physical symptoms.

Providers may also encourage patients to make lifestyle changes to improve symptoms. Those lifestyle changes may include:

- Limiting caffeine intake

- Eating meals regularly to balance blood sugar

- Exercising regularly

- Practicing stress management using breathing exercises and meditation

- Having regular therapy sessions and attending peer support groups

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

If you or anyone you know is considering suicide or self-harm or is anxious, depressed, upset, or needs to talk, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741. For international resources, here is a good place to begin.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mastering Gut Health for Women – by Karín Feltman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The author, a registered nurse, has a focus on holistic health, and in this book it’s all about wellness from the inside out.

To effect this, she lays out a 12-week program of transformations:

- Week 1: transform your knowledge

- Week 2: transform your brain

- Week 3: transform your digestion

- Week 4: transform your immunity

- Week 5: transform your emotions

- Week 6: transform your sleep

- Week 7: transform your energy/vitality

- Week 8: transform your activity

- Week 9: transform your hormones

- Week 10: transform your diet

- Week 11: transform your weight

- Week 12: transform your habits

Which all adds up to quite a comprehensive overall transformation!

Of course, it’s possible you might want to implement everything at once; an exciting prospect for sure, but oftentimes it really is best to just change one thing at once before moving on; that way it’s a lot more likely to stick, and that’s why she presents it in this format.

On the other hand, maybe you might want to take longer than the 12 weeks, if for example it takes you more than a week to do a certain part. That’s fine too, though for most people without serious constraints (or suffering some unexpected major interruption to your usual life), the 12-week program should be quite doable as-is.

The style is personable and friendly, albeit with frequent references to science and appropriate citations.

Bottom line: the title centers gut health, and so does the book itself, but this is truly a holistic approach that goes far beyond the gut, which makes it even more worthwhile.

Click here to check out Mastering Gut Health For Women, and master gut health for yourself!

Share This Post

-

Machine-Dispensed Coffee & Heart Health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We have written before about the health benefits (and risks) of coffee; for most people, the benefits far outweigh the risks, but individual cases may vary:

The Bitter Truth About Coffee (or is it?) ← this is a mythbusting edition

Speaking of bitterness; coffee has abundant polyphenols, which means…

- Coffee is the world’s biggest source of antioxidants

- 65% reduced risk of Alzheimer’s for coffee-drinkers

- 67% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes for coffee-drinkers

- 43% reduced risk of liver cancer for coffee-drinkers

- 53% reduced suicide risk for coffee-drinkers

See also: Why Bitter Is Better: Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain ← while it says foods in the title, this does cover coffee too.

For mythbusting on caffeine specifically, enjoy: Caffeine: Cognitive Enhancer Or Brain-Wrecker?

There are also gut health benefits from drinking coffee, and what’s good for our gut is invariably good for our heart and brain:

Coffee & Your Gut ← gut bacteria do not, by the way, have a preference about how you make your coffee or whether it is caffeinated or not

The latest science on coffee and heart health

Specifically, on coffee and cholesterol levels, so for a quick primer on cholesterol, check out: Demystifying Cholesterol

High total cholesterol, and especially high LDL (“bad” cholesterol) is generally associated with cardiovascular disease, for the reasons outlined in the link above.

Recently, researchers at Uppsala University in Sweden examined the levels of cafestol and kahweol, which are both diterpenes, substances known to increase cholesterol levels, in coffee made by various methods, including those dispensed from coffee machines in workplaces.

Two samples were taken from each machine every 2–3 weeks, and the most common kinds of machines produced the highest concentrations of diterpenes. These machines are the ones that push hot water through a small amount of ground coffee, through a wide-gauge filter, dispensing coffee into a cup in about 30 seconds.

Actual espresso machines, which work on the same principle but usually with a finer filter, higher pressure, and slower dispensing of the drink, had widely varying results, quite possibly because there is (in most machines) a human element in how tightly the ground coffee is packed into the metal filter basket.

Simple filter coffee, whether made in a coffee percolator machine or made using the pour-over method, had the lowest concentrations of diterpenes.

You can read about this study here:

However!

We were curious as to how, exactly, cafestol and kahweol increase cholesterol levels.

It turns out that research in this area has been scant, because most mice aren’t affected by it in the way that most humans are, which has limited mouse model studies.

Scant does not mean non-existent, though, and the answer came by virtue of transgenic mice (specifically, apolipoprotein (apo) E*3-Leiden transgenic mice, which do have the same reaction to cafestol as humans), the paper title sums it up nicely:

You may be wondering: what does suppression of bile acid synthesis have to do with cholesterol levels?

To oversimplify it a bit: cafestol messes with cholesterol metabolism by interfering with the enzymes involved in cholesterol metabolism (specifically, regulatory enzymes found in bile acid).

As to what it actually does in that regard: it reduces LDLR (LDL receptor) mRNA levels by 37% (that figure’s an average of the specific enzymes, sterol 27-hydroxylase and oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase, which were reduced by 32% and 48%, respectively).

Why this matters in practical terms: cafestol does not add any cholesterol to our systems, it inhibits our ability to clear LDL cholesterol, thus promoting raised LDL cholesterol levels.

In other words: if you have little or no dietary cholesterol (no dietary cholesterol, for example, if you are vegan), then your body will only have the cholesterol that it made for itself because it needed it, and as such, the body won’t need to do the same kind of clean-up job that it would if you had that coffee with a double cheeseburger with extra bacon.

As such, if you have little or no dietary cholesterol, cafestol is unlikely to have anything like the same effect on cholesterol levels.

Disclaimer: this latter is technically a hypothesis, but based on sound reasoning:

It’s the same logic that says “if you do not drink alcohol, then eating a durian fruit, which inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, which the body uses to metabolize alcohol, will not cause alcohol-related problems for you”.

Want to know more?

We wrote previously on coffee and cafestol, along with some suggestions:

Health-Hack Your Coffee To Make Your Coffee Heart-Healthier!

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Heal & Reenergize Your Brain With Optimized Sleep Cycles

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sometimes 8 hours sleep can result in grogginess while 6 hours can result in waking up fresh as a daisy, so what gives? Dr. Tracey Marks explains, in this short video.

Getting more than Zs in

Sleep involves 90-minute cycles, usually in 4 stages:

- Stage 1: (drowsy state): brief muscle jerks; lasts a few minutes.

- Stage 2: (light sleep): sleep spindles for memory consolidation; 50% of total sleep.

- Stage 3 (deep sleep): tissue repair, immune support, brain toxin removal via the glymphatic system.

- Stage 4 (REM sleep): emotional processing, creativity, problem-solving, and dreaming.

Some things can disrupt some or all of those. To give a few common examples:

- Alcohol: impairs REM sleep.

- Caffeine: hinders deep sleep even if consumed hours before bed.

- Screentime: delays sleep onset due to blue light (but not by much); the greater problem is that it can also disrupt REM sleep due to mental stimulation.

To optimize things, Dr. Marks recommends:

- 90-minute rule: plan sleep to align with full cycles (e.g: 22:30 to 06:00 = 7½ hours, which is 5x 90-minute cycles).

- Smart alarms: use sleep-tracking apps with built-in alarm, to wake you up during light sleep phases.

- Strategic naps: keep naps to 20 minutes or a full 90-minute cycle.

- Pink noise: improves deep sleep.

- Meal timing: avoid eating within 3 hours of bedtime.

- Natural light: get morning light exposure in the morning to strengthen circadian rhythm.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Calculate (And Enjoy) The Perfect Night’s Sleep

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

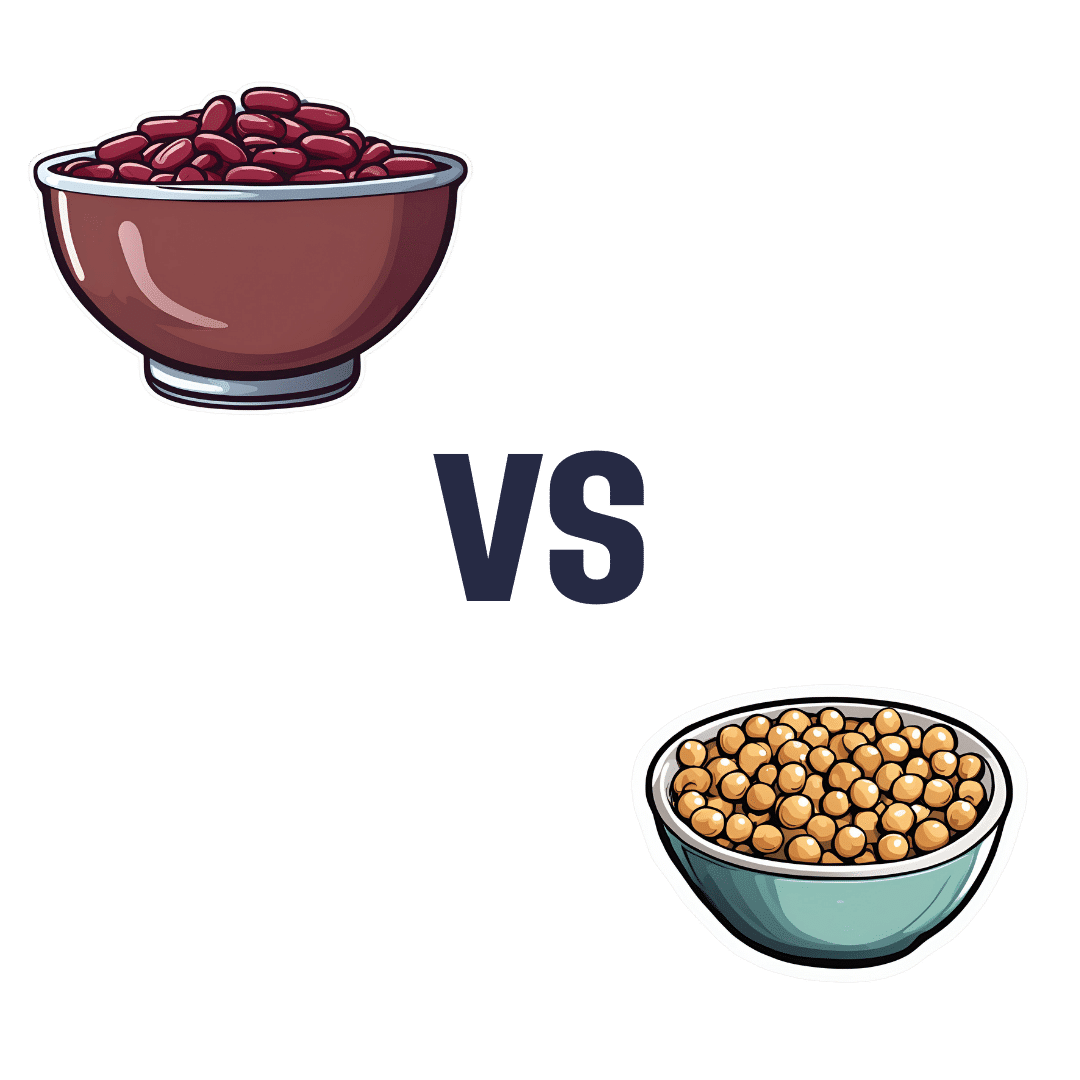

Kidney Beans vs Chickpeas – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kidney beans to chickpeas, we picked the chickpeas.

Why?

Both are great! But there’s a clear winner here today:

In terms of macros, chickpeas have more protein, carbs, and fiber, making them the more nutrient-dense option in this category.

In the category of vitamins, kidney beans have more of vitamins B1, B3, and K, while chickpeas have more of vitamins A, B2, B5, B6, B7, B9, C, E, and choline, taking the victory again here.

When it comes to minerals, it’s a similar story: kidney beans have more potassium, while chickpeas have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc. Another easy win for chickpeas.

Adding up the three wins makes chickpeas the clear overall winner, but of course, as ever, enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is a virtual emergency department? And when should you ‘visit’ one?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For many Australians the emergency department (ED) is the physical and emblematic front door to accessing urgent health-care services.

But health-care services are evolving rapidly to meet the population’s changing needs. In recent years, we’ve seen growing use of telephone, video, and online health services, including the national healthdirect helpline, 13YARN (a crisis support service for First Nations people), state-funded lines like 13 HEALTH, and bulk-billed telehealth services, which have helped millions of Australians to access health care on demand and from home.

The ED is similarly expanding into new telehealth models to improve access to emergency medical care. Virtual EDs allow people to access the expertise of a hospital ED through their phone, computer or tablet.

All Australian states and the Northern Territory have some form of virtual ED at least in development, although not all of these services are available to the general public at this stage.

So what is a virtual ED, and when is it appropriate to consider using one?

Shutterstock/Nils Versemann How does a virtual ED work?

A virtual ED is set up to mirror the way you would enter the physical ED front door. First you provide some basic information to administration staff, then you are triaged by a nurse (this means they categorise the level of urgency of your case), then you see the ED doctor. Generally, this all takes place in a single video call.

In some instances, virtual ED clinicians may consult with other specialists such as neurologists, cardiologists or trauma experts to make clinical decisions.

A virtual ED is not suitable for managing medical emergencies which would require immediate resuscitation, or potentially serious chest pains, difficulty breathing or severe injuries.

A virtual ED is best suited to conditions that require immediate attention but are not life-threatening. These could include wounds, sprains, respiratory illnesses, allergic reactions, rashes, bites, pain, infections, minor burns, children with fevers, gastroenteritis, vertigo, high blood pressure, and many more.

People with these sorts of conditions and concerns may not be able to get in to see a GP straight away and may feel they need emergency advice, care or treatment.

When attending the ED, they can be subject to long wait times and delayed specialist attention because more serious cases are naturally prioritised. Attending a virtual ED may mean they’re seen by a doctor more quickly, and can begin any relevant treatment sooner.

From the perspective of the health-care system, virtual EDs are about redirecting unnecessary presentations away from physical EDs, helping them be ready to respond to emergencies. The virtual ED will not hesitate in directing callers to come into the physical ED if staff believe it is an emergency.

The doctor in the virtual ED may also direct the patient to a GP or other health professional, for example if their condition can’t be assessed visually, or if they need physical treatment.

The results so far

Virtual EDs have developed significantly over the past three years, predominantly driven by the COVID pandemic. We are now starting to slowly see assessments of these services.

A recent evaluation my colleagues and I did of Queensland’s Metro North Virtual ED found roughly 30% of calls were directed to the physical ED. This suggests 70% of the time, cases could be managed effectively by the virtual ED.

Preliminary data from a Victorian virtual ED indicates it curbed a similar rate of avoidable ED presentations – 72% of patients were successfully managed by the virtual ED alone. A study on the cost-effectiveness of another Victorian virtual ED suggested it has the potential to generate savings in health-care costs if it prevents physical ED visits.

Only 1.2% of people assessed in Queensland’s Metro North Virtual ED required unexpected hospital admission within 48 hours of being “discharged” from the virtual ED. None of these cases were life-threatening. This indicates the virtual ED is very safe.

The service experienced an average growth rate of 65% each month over a two-year evaluation period, highlighting increasing demand and confidence in the service. Surveys suggested clinicians also view the virtual ED positively.

The right advice could tell you whether you need to visit hospital in person or not. 1st footage/Shutterstock What now?

We need further research into patient outcomes and satisfaction, as well as the demographics of those using virtual EDs, and how these measures compare to the physical ED across different triage categories.

There are also challenges associated with virtual EDs, including around technology (connection and skills among patients and health professionals), training (for health professionals) and the importance of maintaining security and privacy.

Nonetheless, these services have the potential to reduce congestion in physical EDs, and offer greater convenience for patients.

Eligibility differs between different programs, so if you want to use a virtual ED, you may need to check you are eligible in your jurisdiction. Most virtual EDs can be accessed online, and some have direct phone numbers.

Jaimon Kelly, Senior Research Fellow in Telehealth delivered health services, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Health Care AI, Intended To Save Money, Turns Out To Require a Lot of Expensive Humans

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Preparing cancer patients for difficult decisions is an oncologist’s job. They don’t always remember to do it, however. At the University of Pennsylvania Health System, doctors are nudged to talk about a patient’s treatment and end-of-life preferences by an artificially intelligent algorithm that predicts the chances of death.

But it’s far from being a set-it-and-forget-it tool. A routine tech checkup revealed the algorithm decayed during the covid-19 pandemic, getting 7 percentage points worse at predicting who would die, according to a 2022 study.

There were likely real-life impacts. Ravi Parikh, an Emory University oncologist who was the study’s lead author, told KFF Health News the tool failed hundreds of times to prompt doctors to initiate that important discussion — possibly heading off unnecessary chemotherapy — with patients who needed it.

He believes several algorithms designed to enhance medical care weakened during the pandemic, not just the one at Penn Medicine. “Many institutions are not routinely monitoring the performance” of their products, Parikh said.

Algorithm glitches are one facet of a dilemma that computer scientists and doctors have long acknowledged but that is starting to puzzle hospital executives and researchers: Artificial intelligence systems require consistent monitoring and staffing to put in place and to keep them working well.

In essence: You need people, and more machines, to make sure the new tools don’t mess up.

“Everybody thinks that AI will help us with our access and capacity and improve care and so on,” said Nigam Shah, chief data scientist at Stanford Health Care. “All of that is nice and good, but if it increases the cost of care by 20%, is that viable?”

Government officials worry hospitals lack the resources to put these technologies through their paces. “I have looked far and wide,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said at a recent agency panel on AI. “I do not believe there’s a single health system, in the United States, that’s capable of validating an AI algorithm that’s put into place in a clinical care system.”

AI is already widespread in health care. Algorithms are used to predict patients’ risk of death or deterioration, to suggest diagnoses or triage patients, to record and summarize visits to save doctors work, and to approve insurance claims.

If tech evangelists are right, the technology will become ubiquitous — and profitable. The investment firm Bessemer Venture Partners has identified some 20 health-focused AI startups on track to make $10 million in revenue each in a year. The FDA has approved nearly a thousand artificially intelligent products.

Evaluating whether these products work is challenging. Evaluating whether they continue to work — or have developed the software equivalent of a blown gasket or leaky engine — is even trickier.

Take a recent study at Yale Medicine evaluating six “early warning systems,” which alert clinicians when patients are likely to deteriorate rapidly. A supercomputer ran the data for several days, said Dana Edelson, a doctor at the University of Chicago and co-founder of a company that provided one algorithm for the study. The process was fruitful, showing huge differences in performance among the six products.

It’s not easy for hospitals and providers to select the best algorithms for their needs. The average doctor doesn’t have a supercomputer sitting around, and there is no Consumer Reports for AI.

“We have no standards,” said Jesse Ehrenfeld, immediate past president of the American Medical Association. “There is nothing I can point you to today that is a standard around how you evaluate, monitor, look at the performance of a model of an algorithm, AI-enabled or not, when it’s deployed.”

Perhaps the most common AI product in doctors’ offices is called ambient documentation, a tech-enabled assistant that listens to and summarizes patient visits. Last year, investors at Rock Health tracked $353 million flowing into these documentation companies. But, Ehrenfeld said, “There is no standard right now for comparing the output of these tools.”

And that’s a problem, when even small errors can be devastating. A team at Stanford University tried using large language models — the technology underlying popular AI tools like ChatGPT — to summarize patients’ medical history. They compared the results with what a physician would write.

“Even in the best case, the models had a 35% error rate,” said Stanford’s Shah. In medicine, “when you’re writing a summary and you forget one word, like ‘fever’ — I mean, that’s a problem, right?”

Sometimes the reasons algorithms fail are fairly logical. For example, changes to underlying data can erode their effectiveness, like when hospitals switch lab providers.

Sometimes, however, the pitfalls yawn open for no apparent reason.

Sandy Aronson, a tech executive at Mass General Brigham’s personalized medicine program in Boston, said that when his team tested one application meant to help genetic counselors locate relevant literature about DNA variants, the product suffered “nondeterminism” — that is, when asked the same question multiple times in a short period, it gave different results.

Aronson is excited about the potential for large language models to summarize knowledge for overburdened genetic counselors, but “the technology needs to improve.”

If metrics and standards are sparse and errors can crop up for strange reasons, what are institutions to do? Invest lots of resources. At Stanford, Shah said, it took eight to 10 months and 115 man-hours just to audit two models for fairness and reliability.

Experts interviewed by KFF Health News floated the idea of artificial intelligence monitoring artificial intelligence, with some (human) data whiz monitoring both. All acknowledged that would require organizations to spend even more money — a tough ask given the realities of hospital budgets and the limited supply of AI tech specialists.

“It’s great to have a vision where we’re melting icebergs in order to have a model monitoring their model,” Shah said. “But is that really what I wanted? How many more people are we going to need?”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: