What is a ‘vaginal birth after caesarean’ or VBAC?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A vaginal birth after caesarean (known as a VBAC) is when a woman who has had a caesarean has a vaginal birth down the track.

In Australia, about 12% of women have a vaginal birth for a subsequent baby after a caesarean. A VBAC is much more common in some other countries, including in several Scandinavian ones, where 45-55% of women have one.

So what’s involved? What are the risks? And who’s most likely to give birth vaginally the next time round?

What happens? What are the risks?

When a woman chooses a VBAC she is cared for much like she would during a planned vaginal birth.

However, an induction of labour is avoided as much as possible, due to the slightly increased risk of the caesarean scar opening up (known as uterine rupture). This is because the medication used in inductions can stimulate strong contractions that put a greater strain on the scar.

In fact, one of the main reasons women may be recommended to have a repeat caesarean over a vaginal birth is due to an increased chance of her caesarean scar rupturing.

This is when layers of the uterus (womb) separate and an emergency caesarean is needed to deliver the baby and repair the uterus.

Uterine rupture is rare. It occurs in about 0.2-0.7% of women with a history of a previous caesarean. A uterine rupture can also happen without a previous caesarean, but this is even rarer.

However, uterine rupture is a medical emergency. A large European study found 13% of babies died after a uterine rupture and 10% of women needed to have their uterus removed.

The risk of uterine rupture increases if women have what’s known as complicated or classical caesarean scars, and for women who have had more than two previous caesareans.

Most care providers recommend you avoid getting pregnant again for around 12 months after a caesarean, to allow full healing of the scar and to reduce the risk of the scar rupturing.

National guidelines recommend women attempt a VBAC in hospital in case emergency care is needed after uterine rupture.

During a VBAC, recommendations are for closer monitoring of the baby’s heart rate and vigilance for abnormal pain that could indicate a rupture is happening.

If labour is not progressing, a caesarean would then usually be advised.

Why avoid multiple caesareans?

There are also risks with repeat caesareans. These include slower recovery, increased risks of the placenta growing abnormally in subsequent pregnancies (placenta accreta), or low in front of the cervix (placenta praevia), and being readmitted to hospital for infection.

Women reported birth trauma and post-traumatic stress more commonly after a caesarean than a vaginal birth, especially if the caesarean was not planned.

Women who had a traumatic caesarean or disrespectful care in their previous birth may choose a VBAC to prevent re-traumatisation and to try to regain control over their birth.

We looked at what happened to women

The most common reason for a caesarean section in Australia is a repeat caesarean. Our new research looked at what this means for VBAC.

We analysed data about 172,000 low-risk women who gave birth for the first time in New South Wales between 2001 and 2016.

We found women who had an initial spontaneous vaginal birth had a 91.3% chance of having subsequent vaginal births. However, if they had a caesarean, their probability of having a VBAC was 4.6% after an elective caesarean and 9% after an emergency one.

We also confirmed what national data and previous studies have shown – there are lower VBAC rates (meaning higher rates of repeat caesareans) in private hospitals compared to public hospitals.

We found the probability of subsequent elective caesarean births was higher in private hospitals (84.9%) compared to public hospitals (76.9%).

Our study did not specifically address why this might be the case. However, we know that in private hospitals women access private obstetric care and experience higher caesarean rates overall.

What increases the chance of success?

When women plan a VBAC there is a 60-80% chance of having a vaginal birth in the next birth.

The success rates are higher for women who are younger, have a lower body mass index, have had a previous vaginal birth, give birth in a home-like environment or with midwife-led care.

For instance, an Australian study found women who accessed continuity of care with a midwife were more likely to have a successful VBAC compared to having no continuity of care and seeing different care providers each time.

An Australian national survey we conducted found having continuity of care with a midwife when planning a VBAC can increase women’s sense of control and confidence, increase their chance to be upright and active in labour and result in a better relationship with their health-care provider.

Why is this important?

With the rise of caesareans globally, including in Australia, it is more important than ever to value vaginal birth and support women to have a VBAC if this is what they choose.

Our research is also a reminder that how a woman gives birth the first time greatly influences how she gives birth after that. For too many women, this can lead to multiple caesareans, not all of them needed.

Hannah Dahlen, Professor of Midwifery, Associate Dean Research and HDR, Midwifery Discipline Leader, Western Sydney University; Hazel Keedle, Senior Lecturer of Midwifery, Western Sydney University, and Lilian Peters, Adjunct Research Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

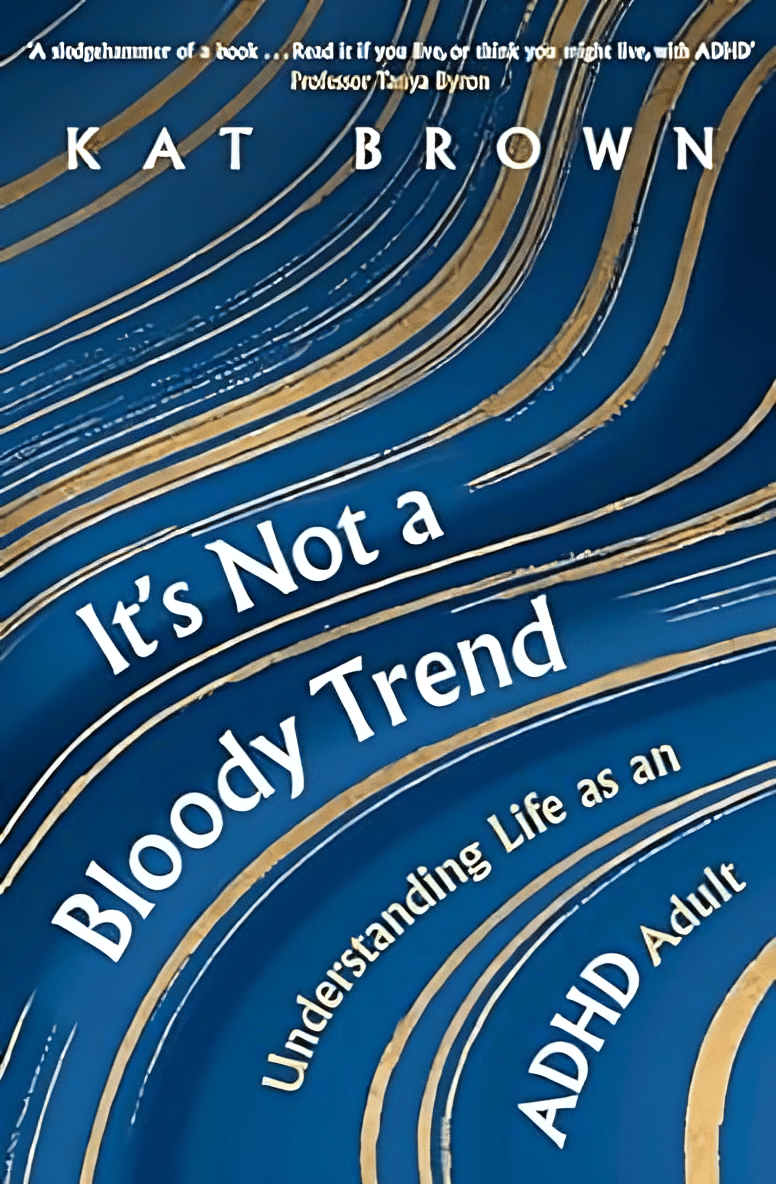

It’s Not A Bloody Trend – by Kat Brown

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one’s not a clinical book, and the author is not a clinician. However, it’s not just a personal account, either. Kat Brown is an award-winning journalist (with ADHD) and has approached this journalistically.

Not just in terms of investigative journalism, either. Rather, also with her knowledge and understanding of the industry, doing for us some meta-journalism and explaining why the press have gone for many misleading headlines.

Which in this case means for example it’s not newsworthy to say that people have gone undiagnosed and untreated for years and that many continue to go unseen; we know this also about such things as endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS. But some more reactionary headlines will always get attention, e.g. “look at these malingering attention-seekers”.

She also digs into the common comorbidities of various conditions, the differences it makes to friendships, families, relationships, work, self-esteem, parenting, and more.

This isn’t a “how to” book, but there’s a lot of value here if a) you have ADHD, and/or b) you spend any amount of time with someone who does.

Bottom line: if you’d like to understand “what all the fuss is about” in one book, this is the one for ADHD.

Share This Post

-

Planning Festivities Your Body Won’t Regret

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Festive Dilemma

For many, Christmas is approaching. Other holidays abound too, and even for the non-observant, it’d be hard to escape seasonal jollities entirely.

So, what’s the plan?

- Eat, drink, and be merry, and have New Year’s Resolutions for the first few days of January before collapsing in a heap?

- Approach the Yuletide with Spartan abstemiousness and miss all the fun while simultaneously annoying your relatives?

Let’s try to find a third approach instead…

What’s festive and healthy?

We’re doing this article this week, because many people will be shopping already, making plans, and so forth. So here are some things to bear in mind:

Make your own mindful choices

Coca-Cola company really did a number on Christmas, but it doesn’t mean their product is truly integral to the season. Same goes for many other things that flood the stores around this time of year. So much sugary confectionary! But remember, they’re not the boss of you. If you wouldn’t buy it ordinarily, why are you buying it now? Do you actually even want it?

If you really do, then you do you, but mindful choices will invariably be healthier than “because there were three additional aisles of confectionary now so I stopped and looked and picked some things”.

Pick your battles

If you’re having a big family gathering, likely there will be occasions with few healthy options available. But you can decide what’s most important for you to avoid, perhaps picking a theme, e.g:

- No alcohol this year, or

- No processed sugary foods, or

- Eat/drink whatever, but practice intermittent fasting

Some resources:

Fight inflammation

This is a big one so it deserves its own category. In the season of sugar and alcohol and fatty meat, inflammation can be a big problem to come around and bite us in the behind. We’ve written on this previously:

Positive dieting

In other words, less of a focus on what to exclude, and more of a focus on what to include in your diet. Fruity drinks and sweets are common at this time of year, but you know what’s also fruity? Fruit!

And it can be festive, too! Berries are great, and those tiny orange-like fruits that may be called clementines or tangerines or satsumas or, as Aldi would have it, “easy peelers”. Apple and cinnamon are also a great combination that both bring sweetness without needing added sugar.

And as for mains? Make your salads that bit fancier, get plenty of greens with your main, have hearty soups and strews with lentils and beams!

See also: Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

Your gut will thank us later!

Get moving!

That doesn’t mean you have to beat the New Year rush to the gym (unless you want to!). But it could mean, for example, more time in your walking shoes (or dancing shoes! With a nod to today’s sponsor) and less time in the armchair.

See also: The doctor who wants us to exercise less; move more

Lastly…

Remember it’s supposed to be fun! And being healthy can be a lot more fun than suffering because of unfortunate choices that we come to regret.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Ayurveda’s Contributions To Science

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ayurveda’s Contributions To Science (Without Being Itself Rooted in Scientific Method)

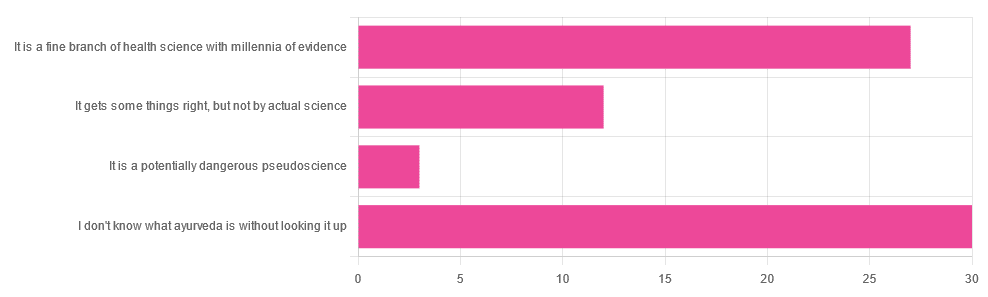

Yesterday, we asked you for your opinions on ayurveda, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses. Of those who responded…

- A little over 41% said “I don’t know what ayurveda is without looking it up”

- A little over 37% said “It is a fine branch of health science with millennia of evidence”

- A little over 16% said “It gets some things right, but not by actual science”

- A little over 4% said “It is a potentially dangerous pseudoscience”

So, what does the science say?

Ayurveda is scientific: True or False?

False, simply. Let’s just rip the band-aid off in this case. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily without merit, though!

Let’s put it this way:

- If you drink coffee to feel more awake because scientific method has discerned that caffeine has vasoconstrictive and adenosine-blocking effects while also promoting dopaminergic activity, then your consumption of coffee is evidence-based and scientific. Great!

- If you drink coffee to feel more awake because somebody told you that that somebody told them that it energizes you by balancing the elements fire (the heat of the coffee), air (the little bubbles on top), earth (the coffee grinds), water (the water), and ether (steam), then that is neither evidence-based nor scientific, but it will still work exactly the same.

Ayurveda is a little like that. It’s an ancient traditional Indian medicine, based on a combination of anecdotal evidence and supposition.

- The anecdotal evidence from ayurveda has often resulted in herbal remedies that, in modern scientific trials, have been found to have merit.

- Ayurvedic meditative practices also have a large overlap with modern mindfulness practices, and have also been found to have merit

- Ayurveda also promotes the practice of yoga, which is indeed a very healthful activity

- The supposition from ayurveda is based largely in those five elements we mentioned above, as well as a “balancing of humors” comparable to medieval European medicine, and from a scientific perspective, is simply a hypothesis with no evidence to support it.

Note: while ayurveda is commonly described as a science by its practitioners in the modern age, it did not originally claim to be scientific, but rather, wisdom handed down directly by the god Dhanvantari.

Ayurveda gets some things right: True or False?

True! Indeed, we covered some before in 10almonds; you may remember:

Bacopa Monnieri: A Well-Evidenced Cognitive Enhancer

(Bacopa monnieri is also known by its name in ayurveda, brahmi)

There are many other herbs that have made their way from ayurveda into modern science, but the above is a stand-out example. Others include:

- Ashwagandha: The Root of All Even-Mindedness?

- Boswellia serrata (Frankincense) Against Pain and Depression/Anxiety

Yoga and meditation are also great, and not only that, but great by science, for example:

- NCCIH | Yoga for Health: Clinical Guidelines, Scientific Literature, Info for Patients

- The Neuroscience of Mindfulness: How Mindfulness Alters the Brain and Facilitates Emotion Regulation

Ayurveda is a potentially dangerous pseudoscience: True or False?

Also True! We covered why it’s a pseudoscience above, but that doesn’t make it potentially dangerous, per se (you’ll remember our coffee example).

What does, however, make it potentially dangerous (dose-dependent) is its use of heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and arsenic:

Heavy Metal Content of Ayurvedic Herbal Medicine Products

Some final thoughts…

Want to learn more about the sometimes beneficial, sometimes uneasy relationship between ayurveda and modern science?

A lot of scholarly articles trying to bridge (or further separate) the two were very biased one way or the other.

Instead, here’s one that’s reasonably optimistic with regard to ayurveda’s potential for good, while being realistic about how it currently stands:

Development of Ayurveda—Tradition to trend

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Proteins Of The Week

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This week’s news round-up is, entirely by chance, somewhat protein-centric in one form or another. So, check out the bad, the very bad, the mostly good, the inconvenient, and the worst:

Mediterranean diet vs the menopause

Researchers looked at hundreds of women with an average age of 51, and took note of their dietary habits vs their menopause symptoms. Most of them were consuming soft drinks and red meat, and not good in terms of meeting the recommendations for key food groups including vegetables, legumes, fruit, fish and nuts, and there was an association between greater adherence to Mediterranean diet principles, and better health.

Read in full: Fewer soft drinks and less red meat may ease menopause symptoms: Study

Related: Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet

Listeria in meat

This one’s not a study, but it is relevant important news. The headline pretty much says it all, so if you don’t eat meat, this isn’t one you need to worry about any further than that. If you do eat meat, though, you might want to check out the below article to find out whether the meat you eat might be carrying listeria:

Read in full: Almost 10 million pounds of meat recalled due to Listeria danger

Related: Frozen/Thawed/Refrozen Meat: How Much Is Safety, And How Much Is Taste?

Brawn and brain?

A study looked at cognitively healthy older adults (of whom, 57% women), and found an association between their muscle strength and their psychological wellbeing. Note that when we said “cognitively healthy”, this means being free from dementia etc—not necessarily psychologically health in all respects, such as also being free from depression and enjoying good self-esteem.

Read in full: Study links muscle strength and mental health in older adults

Related: Staying Strong: Tips To Prevent Muscle Loss With Age

The protein that blocks bone formation

This one’s more clinical but definitely of interest to any with osteoporosis or at high risk of osteoporosis. Researchers identified a specific protein that blocks osteoblast function, thus more of this protein means less bone production. Currently, this is not something that we as individuals can do anything about at home, but it is promising for future osteoporosis meds development.

Read in full: Protein blocking bone development could hold clues for future osteoporosis treatment

Related: Which Osteoporosis Medication, If Any, Is Right For You?

Rabies risk

People associate rabies with “rabid dogs”, but the biggest rabies threat is actually bats, and they don’t even need to necessarily bite you to confer the disease (it suffices to have licked the skin, for instance—and bats are basically sky-puppies who will lick anything). Because rabies has a 100% fatality rate in unvaccinated humans, this is very serious. This means that if you wake up and there’s a bat in the house, it doesn’t matter if it hasn’t bitten anyone; get thee to a hospital (where you can get the vaccine before the disease takes hold; this will still be very unpleasant but you’ll probably survive so long as you get the vaccine in time).

Read in full: What to know about bats and rabies

Related: Dodging Dengue In The US ← much less serious than rabies, but still not to be trifled with—particularly noteworthy if you’re in an area currently affected by floodwaters or even just unusually heavy rain, by the way, as this will leave standing water in which mosquitos breed.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

I Will Make You Passionate About Exercise – by Bevan Eyles

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What this isn’t: a “just do it!” motivational pep-talk.

What this is:a compassionate and thoughtful approach to help non-exercisers become regular exercisers, by looking at the real life factors of what holds people back (learning from his own early failures as a coach, by paying attention now to things he inadvertently neglected back then), both in the material/practical and in the psychological/emotional.

Further, he gives a 10-step method, for those who would like to be walked through it by the hand, making the transition to exercising regularly (and as a leisure habit, rather than as a chore) as frictionless as possible.

The style is friendly and energetic, and very easy-reading throughout.

Bottom line: if you are someone who finds exercising to be a chore, this book can definitely help you “get from here to there” in terms of finding joy in it, and finding exercise even easier than not exercising. Yes, really.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Natural Facelift – by Sophie Perry

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this book isn’t: it’s mostly not about beauty, and it’s certainly not about ageist ideals of “hiding” aging.

The author herself discusses the privilege that is aging (not everyone gets to do it) and the importance of taking thankful pride in our lived-in bodies.

The title and blurb belie the contents of the book rather. Doubtlessly the publisher felt that extrinsic beauty would sell better than intrinsic wellbeing. As for what it’s actually more about…

Ever splashed your face in cold water to feel better? This book’s about revitalising the complex array of facial muscles (there are anatomical diagrams) and the often-tired and very diverse tissues that cover them, complete with the array of nerve endings very close to your CNS (not to mention the vagus nerve running just behind your jaw), and some of the most important blood vessels of your body, serving your brain.

With all that in mind, this book, full of useful therapeutic techniques, is a very, very far cry from “massage like this and you’ll look like you got photoshopped”.

The style varies, as some parts of explanation of principles, or anatomy, and others are hands-on (literally) guides to the exercises, but it is all very clear and easy to understand/follow.

Bottom line: aspects of conventional beauty may be a side-effect of applying the invigorating exercises described in this book. The real beauty is—literally—more than skin-deep.

Click here to check out The Natural Facelift, and order yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: