The Blue Zones Kitchen – by Dan Buettner

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Buettner’s other book, The Blue Zones: 9 Lessons For Living Longer From The People Who’ve Lived The Longest, and with this one, it’s now time to focus on the dietary aspect.

As the title and subtitle promises, we get 100 recipes, inspired by Blue Zone cuisines. The recipes themselves have been tweaked a little for maximum healthiness, eliminating some ingredients that do crop up in the Blue Zones but are exceptions to their higher average healthiness rather than the rule.

The recipes are arranged by geographic zone rather than by meal type, so it might take a full read-through before knowing where to find everything, but it makes it a very enjoyable “coffee-table book” to browse, as well as being practical in the kitchen. The ingredients are mostly easy to find globally, and most can be acquired at a large supermarket and/or health food store. In the case of substitutions, most are obvious, e.g. if you don’t have wild fennel where you are, use cultivated, for example.

In the category of criticism, it appears that Buettner is very unfamiliar with spices, and so has skipped them almost entirely. We at 10almonds could never skip them, and heartily recommend adding your own spices, for their health benefits and flavors. It may take a little experimentation to know what will work with what recipes, but if you’re accustomed to cooking with spices normally, it’s unlikely that you’ll err by going with your heart here.

Bottom line: we’d give this book a once-over for spice additions, but aside from that, it’s a fine book of cuisine-by-location cooking.

Click here to check out The Blue Zones Kitchen, and get cooking into your own three digits!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Everything You Need To Know About The Menopause – by Kate Muir

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Kate Muir has made a career out of fighting for peri-menopausal health to be taken seriously. Because… it’s actually far more serious than most people know.

What people usually know:

- No more periods

- Hot flushes

- “I dunno, some annoying facial hairs maybe”

The reality encompasses a lot more, and Muir covers topics including:

- Workplace struggles (completely unnecessary ones)

- Changes to our sex life (not usually good ones, by default!)

- Relationship between menopause and breast cancer

- Relationship between menopause and Alzheimer’s

“Wait”, you say, “correlation is not causation, that last one’s just an age thing”, and that’d be true if it weren’t for the fact that receiving Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) or not is strongly correlated with avoiding Alzheimer’s or not.

The breast cancer thing is not to be downplayed either. Taking estrogen comes with a stated risk of breast cancer… But what they don’t tell you, is that for many people, not taking it comes with a higher risk of breast cancer (but that’s not the doctor’s problem, in that case). It’s one of those situations where fear of litigation can easily overrule good science.

This kind of thing, and much more, makes up a lot of the meat of this book.

Hormonal treatment for the menopause is often framed in the wider world as a whimsical luxury, not a serious matter of health…. If you’ve ever wondered whether you might want something different, something better, as part of your general menopause plan (you have a plan for this important stage of your life, right?), this is a powerful handbook for you.

Additionally, if (like many!) you justifiably fear your doctor may brush you off (or in the case of mood disorders, may try to satisfy you with antidepressants to treat the symptom, rather than HRT to treat the cause), this book will arm you as necessary to help you get what you need.

Grab your copy of “Everything You Need To Know About The Menopause” from Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

Jasmine McDonald’s Ballet Stretching Routine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Why Jasmine’s Video is Useful

Jasmine McDonald is not only a professional ballerina, but is also a certified personal trainer, so when it comes to keeping her body strong and flexible, she’s a wealth of knowledge. Her video (below) is a great example of this.

In case you’re interested in learning more, she currently (privately) tutors over 30 people on a day-to-day basis. You can contact her here!

Other Stretches?

If you think that Jasmine’s stretches may be out of your league, we recommend checking out our other articles on stretching, including:

- 11 Minutes to Pain-Free Hips

- How to Permanently Loosen a Tight Psoas

- Stretching Scientifically

- Stretching & Mobility

- Stretching to Stay Young

Otherwise, let loose on these dancer stretches and exercises:

How did you find that video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

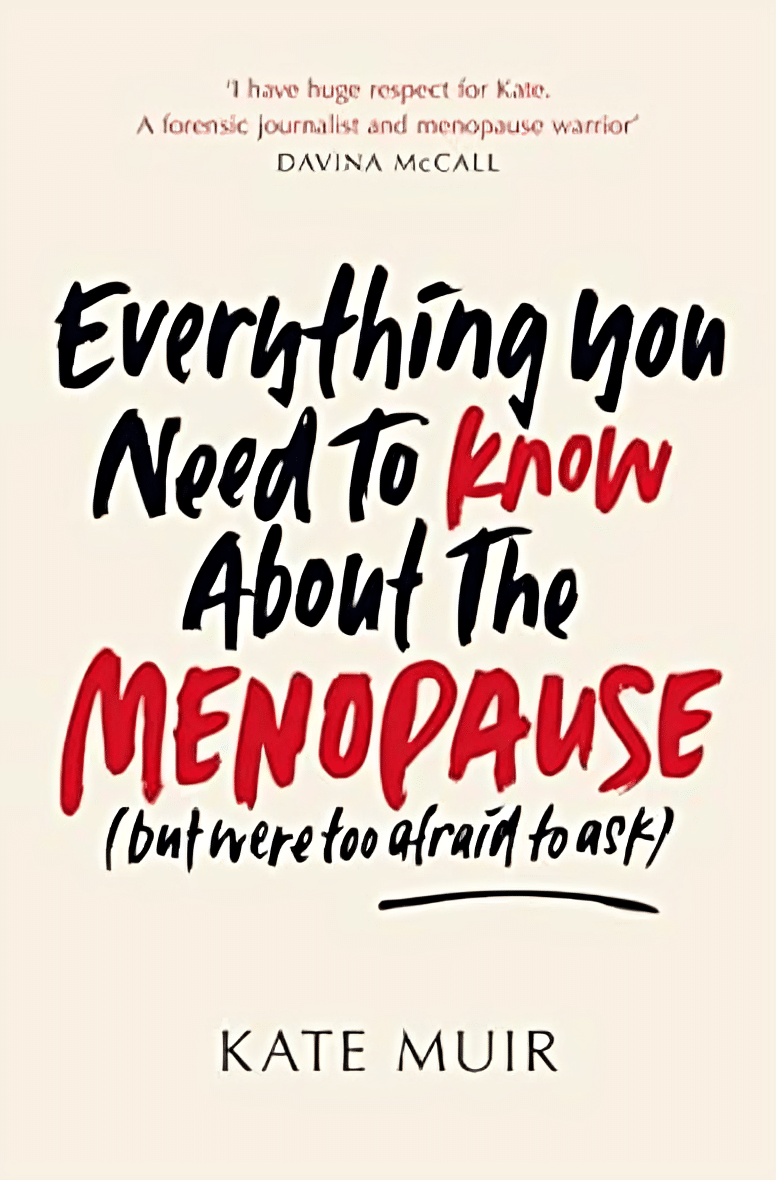

Quercetin Quinoa Probiotic Salad

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This quercetin-rich salad is a bit like a tabbouleh in feel, with half of the ingredients switched out to maximize phenolic and gut-healthy benefits.

You will need

- ½ cup quinoa

- ½ cup kale, finely chopped

- ½ cup flat leaf parsley, finely chopped

- ½ cup green olives, thinly sliced

- ½ cup sun-dried tomatoes, roughly chopped

- 1 pomegranate, peel and pith removed

- 1 preserved lemon, finely chopped

- 1 oz feta cheese or plant-based equivalent, crumbled

- 1 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- 1 tbsp capers

- 1 tbsp chia seeds

- 1 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

Note: you shouldn’t need salt or similar here, because of the diverse gut-healthy fermented products bringing their own salt with them

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Rinse the quinoa, add the tbsp of chia seeds, cook as normal for quinoa (i.e. add hot water, bring to boil, simmer for 15 minutes or so until pearly and tender), carefully (don’t lose the chia seeds; use a sieve) drain and rinse with cold water to cool. Shake off excess water and/or pat dry on kitchen paper if necessary.

2) Mix everything gently but thoroughly.

3) Serve:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Tasty Tabbouleh with Tahini ← in case you want an actual tabbouleh

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

- Fight Inflammation & Protect Your Brain, With Quercetin

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Who Initiates Sex & Why It Matters

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In an ideal world, it wouldn’t matter any more than who first says “let’s get something to eat” when hungry. But in reality, it can cause serious problems on both sides:

Fear and loathing?

The person who initiates gets the special prize of an n% chance of experiencing rejection, and then what? Try again, and again, and risk seeming pushy? Or leave the ball in the other person’s court, where it may then go untouched for the next few months, because (in the most positive scenario) they were waiting for you to initiate at a better time for them?

The person who does not initiate, and/but does not want sex at that time, gets the special prize of either making their partner feel unwanted, insecure, and perhaps unloved, or else grudgingly consenting to sex that’s going to be no fun while your heart’s not in it, and thus create the same end result plus you had an extra bad experience?

So, that sucks all around:

- Initiating touch (sex or cuddling) can feel like a test of being wanted, whereupon a lack of initiation or response may be misinterpreted as a lack of love or appreciation.

- Meanwhile, non-reciprocation might stem from exhaustion or unrelated issues. For many, it’s a physiological lottery.

10almonds note: not discussed in this video, but for many couples, problems can also arise because one partner or another just isn’t showing up with the expected physical signs of physiological arousal, so even if they say (and mean!) an enthusiastic “yes”, their body’s signs get misread as a “not really, though”, resulting in one partner feeling rejected, and both feeling inadequate—on account of something that was completely unrelated to how the person actually felt about the prospect of sex*.

*Sometimes, physiological arousal will simply not accompany psychological arousal, no matter how sincere the latter. And on the flipside, sometimes the signs of physiological arousal will just show up without psychological arousal. The human body is just like that sometimes. We all must listen to our partners’ words, not their genitals!

The solution to this problem is thus the same as the solution to the rest of the problem that is discussed in the video, and it’s: good communication.

That can be easier said than done, of course—not everyone is at their most eloquent in such situations! Which is why it can be important to have those conversations first outside of the bedroom when the stakes are low/non-existent.

Even with the best communication, a more general, overarching non-reciprocity (real or perceived) of sexual desire can cause bitterness, resentment, and can ultimately be relationship-ending if a resolution that’s acceptable to everyone involved is not found.

Ultimately, the work as a couple must begin from within as individuals—addressing self-worth issues to better navigate love and intimacy.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Relationships: When To Stick It Out & When To Call It Quits

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

3 Things Everyone Over 50 Must Do Daily for Healthy Feet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Will Harlow, the over-50s specialist physio, wants you to be on a good footing:

Daily steps in the right direction

The three daily exercises recommended in the video are:

Exercise 1: Towel Scrunch

The towel scrunch exercise strengthens the flexor muscles in the feet, improving balance and improving contact with the ground. To do this exercise, sit on a chair with a towel placed on the floor beneath your toes while keeping your heels on the ground. Use only your toes to pull the towel toward your heel, scrunching it up as much as possible. This movement strengthens the arch of the foot and can help alleviate symptoms of flat feet. For best results, practice this exercise for 2–3 minutes once or twice daily. Once you’ve got the hand of doing it sitting, do it while standing.

Exercise 2: Big Toe Extension

Big toe extension is an essential exercise for maintaining foot mobility and improving walking kinesthetics by preventing stiffness in the big toe. To do this exercise, keep your foot flat on the floor and try to lift only your big toe while keeping the four other toes firmly pressed down. To be clear, we mean under its own power; not using your hands to help. Many people find this difficult initially, but it’s due to a loss of neural connection rather than muscle strength, so with practice, the ability to isolate the movement improves quite quickly. Perform 10 repetitions in a row, three times per day, for optimal benefits. Once you’ve got the hand of doing it sitting, do it while standing.

Exercise 3: Calf Stretch

The calf stretch is an important exercise for maintaining foot health by preventing tight calves, which can contribute to issues like plantar fasciitis and Morton’s neuroma. To do this stretch, place your hands against a wall for support and extend one leg straight behind you while keeping your other heel firmly on the floor. The front knee should be bent while the back leg remains straight, creating a stretch in the calf. Hold this position for 30 seconds (building up to that, if necessary). Since the effectiveness of stretching comes from frequency rather than duration, this stretch should be performed three to four times per day for the best results.

For more on each of these, plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Steps For Keeping Your Feet A Healthy Foundation ← this one’s about general habits, not exercises

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Fermenting Everything – by Andy Hamilton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is not justanother pickling book! This is, instead, what it says on the front cover, “fermenting everything”.

Ok, maybe not literally everything, but every kind of thing that can reasonably be fermented, and it’s probably a lot more things than you might think.

From habanero chutney to lacto-lemonade, aioli to kombucha, Ukrainian fermented tomatoes to kvass. We could go on, but we’d soon run out of space. You get the idea. If it’s a fermented product (food, drink, condiment) and you’ve heard of it, there’s probably a recipe in here.

All in all, this is a great way to get in your gut-healthy daily dose of fermented products!

He does also talk safety, and troubleshooting too. And so long as you have a collection of big jars and a fairly normally-furnished kitchen, you shouldn’t need any more special equipment than that, unless you decide to you your fermentation skills for making beer (which does need some extra equipment, and he offers advice on that—our advice as a health science publication is “don’t drink beer”, though).

Bottom line: with this in hand, you can create a lot of amazing foods/drinks/condiments that are not only delicious, but also great for gut health.

Click here to check out Fermenting Everything, and widen your culinary horizons!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: