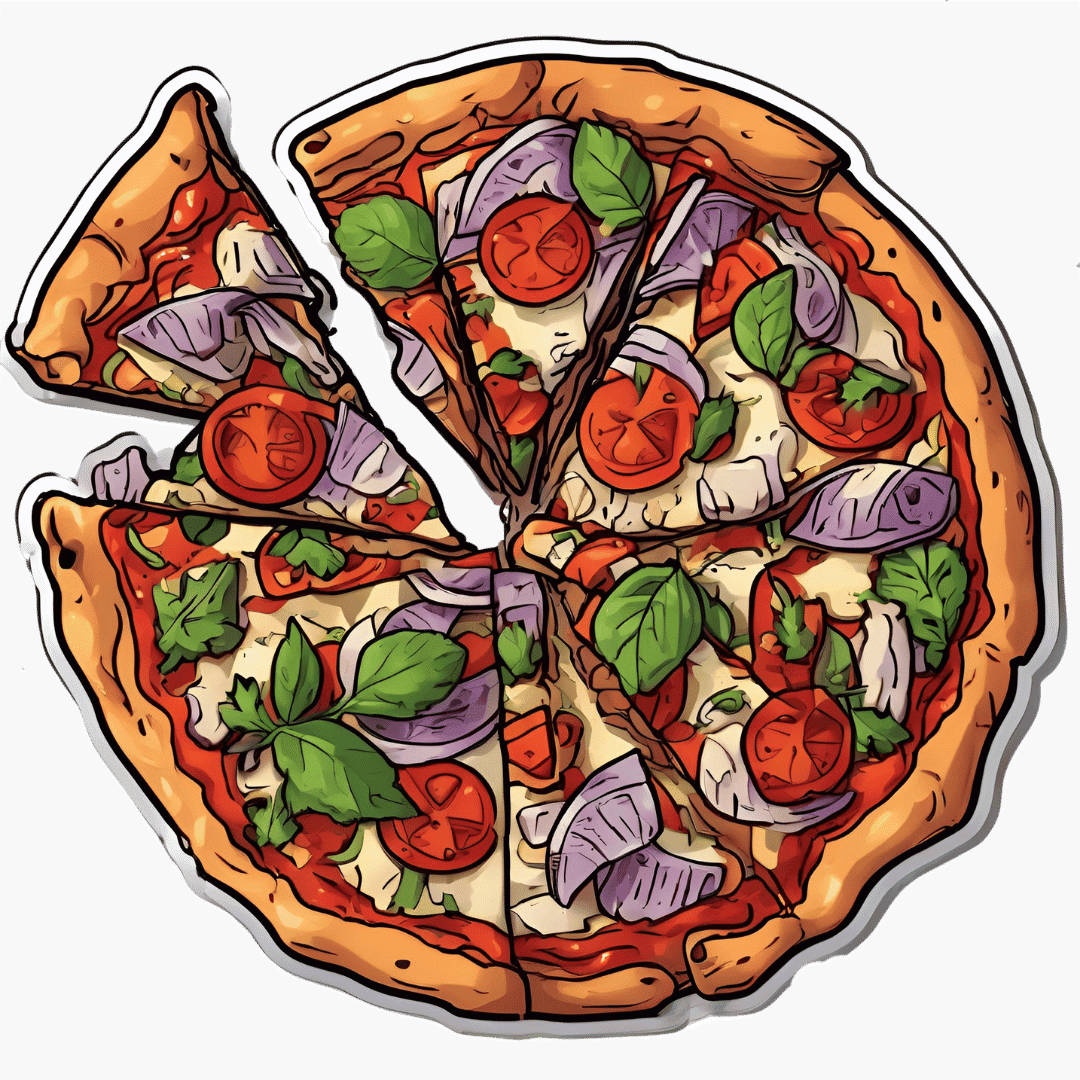

Superfood Pesto Pizza

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Not only is this pizza full of foods that punch above their weight healthwise, there’s no kneading and no waiting when it comes to the base, either. Homemade pizzas made easy!

You will need

For the topping:

- 1 zucchini, sliced

- 1 red bell pepper, cut into strips

- 3 oz mushrooms, sliced

- 3 shallots, cut into quarters

- 6 sun-dried tomatoes, roughly chopped

- ½ bulb garlic (paperwork done, but cloves left intact, unless they are very large, in which case halve them)

- 1 oz pitted black olives, halved

- 1 handful arugula

- 1 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 2 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

For the base:

- ½ cup chickpea flour (also called besan or gram flour)

- 2 tsp extra virgin olive oil

- ½ tsp baking powder

- ⅛ tsp MSG or ¼ tsp low-sodium salt

For the pesto sauce:

- 1 large bunch basil, chopped

- ½ avocado, pitted and peeled

- 1 oz pine nuts

- ¼ bulb garlic, crushed

- 2 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tsp black pepper

- Juice of ½ lemon

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 400℉ / 200℃.

2) Toss the zucchini, bell pepper, mushrooms, shallots, and garlic cloves in 1 tbsp olive oil, ensuring an even coating. Season with the black pepper and MSG/salt, and put on a baking tray lined with baking paper, to roast for about 20 minutes, until they are slightly charred.

3) When the vegetables are in the oven, make the pizza base by combining the dry ingredients in a bowl, making a pit in the middle of it, adding the olive oil and whisking it in, and then slowly (i.e., a little bit at a time) whisking in 1 cup cold water. This should take under 5 minutes.

4) Don’t panic when this doesn’t become a dough; it is supposed to be a thick batter, so that’s fine. Pour it into a 9″ pizza pan, and bake for about 15 minutes, until firm. Rotate it if necessary partway through; whether it needs this or not will depend on your oven.

5) While the pizza base is in the oven, make the pesto sauce by blending all the pesto sauce ingredients in a high-speed blender until smooth.

6) When the base and vegetables are ready (these should be finished around the same time), spread the pesto sauce on the base, scatter the arugula over it followed by the vegetables and then the olives and sun-dried tomatoes.

7) Serve, adding any garnish or other final touches that take your fancy.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Which Bell Peppers To Pick? A Spectrum Of Specialties

- Ergothioneine In Mushrooms: “The Longevity Vitamin” (That’s Not A Vitamin)

- Black Olives vs Green Olives – Which is Healthier

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More

- Coconut vs Avocado – Which is Healthier?

- Herbs for Evidence-Based Health & Healing

- Spermidine For Longevity

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Miracle of Flexibility – by Miranda Esmonde-White

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed books about stretching before, so what makes this one different?

Mostly, it’s that this one takes a holistic approach, making the argument for looking after all parts of flexibility (even parts that might seem useless) because if one bit of us isn’t flexible, the others will start to suffer in compensation because of how that affects our posture, or movement, or in many cases our lack of movement.

Esmonde-White’s “flexibility, from your toes to your shoulders” approach is very consistent with her background as a professional ballet dancer, and now she brings it into her profession as a coach.

The book’s not just about stretching, though. It looks at problems and what can go wrong with posture and the body’s “musculoskeletal trifecta”, and also shares daily training routines that are tailored for specific sporting interests, and/or for those with specific chronic conditions and/or chronic pain. Working around what needs to be worked around, but also looking at strengthening what can be strengthened and fixing what can be fixed along the way.

Bottom line: if your flexibility needs an overhaul, this book is a very good “one-stop shop” for that.

Click here to check out The Miracle Of Flexibility, and discover what you can do!

Share This Post

-

Mind Gym – by Gary Mack and David Casstevens

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

While this book seems to be mostly popular amongst young American college athletes and those around them (coaches, parents, etc) its applicability is a lot wider than that.

The thing is, as this book details, we don’t have to settle for less than optimal in our training—whatever “optimal” means for us, at any stage of life.

The style is largely narrative, and conveys a lot of ideas through anecdotes. They are probably true, but whether they occured entirely as-written or have been polished or embellished is not so important, as to to give food for thought, and reflection on how we can hone what we’re doing to work the best for us.

Nor is it just a long pep-talk, though it certainly has a motivational aspect. But rather, it covers also such things as the seven critical areas that we need to excel at if we want to be mentally robust, and—counterintuitively—the value of slowing down sometimes. The authors also talk about the importance of love, labor, and ongoing learning if we want a fulfilled life.

Bottom line: if you are engaged with any sport or sport-like endeavor that you’d like to be better at, this book will sharpen your training and development.

Share This Post

-

America Worries About Health Costs — And Voters Want to Hear From Biden and Republicans

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

President Joe Biden is counting on outrage over abortion restrictions to help drive turnout for his reelection. Former President Donald Trump is promising to take another swing at repealing Obamacare.

But around America’s kitchen tables, those are hardly the only health topics voters want to hear about in the 2024 campaigns. A new KFF tracking poll shows that health care tops the list of basic expenses Americans worry about — more than gas, food, and rent. Nearly 3 in 4 adults — and majorities of both parties — say they’re concerned about paying for unexpected medical bills and other health costs.

“Absolutely health care is something on my mind,” Rob Werner, 64, of Concord, New Hampshire, said in an interview at a local coffee shop in January. He’s a Biden supporter and said he wants to make sure the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, is retained and that there’s more of an effort to control health care costs.

The presidential election is likely to turn on the simple question of whether Americans want Trump back in the White House. (Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor and U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, remained in the race for the Republican nomination ahead of Super Tuesday, though she had lost the first four primary contests.) And neither major party is basing their campaigns on health care promises.

But in the KFF poll, 80% of adults said they think it’s “very important” to hear presidential candidates talk about what they’d do to address health care costs — a subject congressional and state-level candidates can also expect to address.

“People are most concerned about out-of-pocket expenses for health care, and rightly so,” said Andrea Ducas, vice president of health policy at the Center for American Progress, a Washington, D.C.-based progressive think tank.

Here’s a look at the major health care issues that could help determine who wins in November.

Abortion

Less than two years after the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to an abortion, it is shaping up to be the biggest health issue in this election.

That was also the case in the 2022 midterm elections, when many voters rallied behind candidates who supported abortion rights and bolstered Democrats to an unexpectedly strong showing. Since the Supreme Court’s decision, voters in six states — including Kansas, Kentucky, and Ohio, where Republicans control the legislatures — have approved state constitutional amendments protecting abortion access.

Polls show that abortion is a key issue to some voters, said Robert Blendon, a public opinion researcher and professor emeritus at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He said up to 30% across the board see it as a “personal” issue, rather than policy — and most of those support abortion rights.

“That’s a lot of voters, if they show up and vote,” Blendon said.

Proposals to further protect — or restrict — abortion access could drive voter turnout. Advocates are working to put abortion-related measures on the ballot in such states as Arizona, Florida, Missouri, and South Dakota this November. A push in Washington toward a nationwide abortion policy could also draw more voters to the polls, Blendon said.

A surprise ruling by the Alabama Supreme Court in February that frozen embryos are children could also shake up the election. It’s an issue that divides even the anti-abortion community, with some who believe that a fertilized egg is a unique new person deserving of full legal rights and protections, and others believing that discarding unused embryos as part of the in vitro fertilization process is a morally acceptable way for couples to have children.

Pricey Prescriptions

Drug costs regularly rank high among voters’ concerns.

In the latest tracking poll, more than half — 55% — said they were very worried about being able to afford prescription drugs.

Biden has tried to address the price of drugs, though his efforts haven’t registered with many voters. While its name doesn’t suggest landmark health policy, the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which the president signed in August 2022, included a provision allowing Medicare to negotiate prices for some of the most expensive drugs. It also capped total out-of-pocket spending for prescription drugs for all Medicare patients, while capping the price of insulin for those with diabetes at $35 a month — a limit some drugmakers have extended to patients with other kinds of insurance.

Drugmakers are fighting the Medicare price negotiation provision in court. Republicans have promised to repeal the IRA, arguing that forcing drugmakers to negotiate lower prices on drugs for Medicare beneficiaries would amount to price controls and stifle innovation. The party has offered no specific alternative, with the GOP-led House focused primarily on targeting pharmacy benefit managers, the arbitrators who control most Americans’ insurance coverage for medicines.

Costs of Coverage

Health care costs continue to rise for many Americans. The cost of employer-sponsored health plans have hit new highs in the past few months, raising costs for employers and workers alike. Experts have attributed the increase to high demand and expensive prices for certain drugs and treatments, notably weight loss drugs, as well as to medical inflation.

Meanwhile, the ACA is popular. The KFF poll found that more adults want to see the program expanded than scaled back. And a record 21.3 million people signed up for coverage in 2024, about 5 million of them new customers.

Enrollment in Republican-dominated states has grown fastest, with year-over-year increases of 80% in West Virginia, nearly 76% in Louisiana, and 62% in Ohio, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Public support for Obamacare and record enrollment in its coverage have made it politically perilous for Republicans to pursue the law’s repeal, especially without a robust alternative. That hasn’t stopped Trump from raising that prospect on the campaign trail, though it’s hard to find any other Republican candidate willing to step out on the same limb.

“The more he talks about it, the more other candidates have to start answering for it,” said Jarrett Lewis, a partner at Public Opinion Strategies, a GOP polling firm.

“Will a conversation about repeal-and-replace resonate with suburban women in Maricopa County?” he said, referring to the populous county in Arizona known for being a political bellwether. “I would steer clear of that if I was a candidate.”

Biden and his campaign have pounced on Trump’s talk of repeal. The president has said he wants to make permanent the enhanced premium subsidies he signed into law during the pandemic that are credited with helping to increase enrollment.

Republican advisers generally recommend that their candidates promote “a market-based system that has the consumer much more engaged,” said Lewis, citing short-term insurance plans as an example. “In the minds of Republicans, there is a pool of people that this would benefit. It may not be beneficial for everyone, but attractive to some.”

Biden and his allies have criticized short-term insurance plans — which Trump made more widely available — as “junk insurance” that doesn’t cover care for serious conditions or illnesses.

Entitlements Are Off-Limits

Both Medicaid and Medicare, the government health insurance programs that cover tens of millions of low-income, disabled, and older people, remain broadly popular with voters, said the Democratic pollster Celinda Lake. That makes it unlikely either party would pursue a platform that includes outright cuts to entitlements. But accusing an opponent of wanting to slash Medicare is a common, and often effective, campaign move.

Although Trump has said he wouldn’t cut Medicare spending, Democrats will likely seek to associate him with other Republicans who support constraining the program’s costs. Polls show that most voters oppose reducing any Medicare benefits, including by raising Medicare’s eligibility age from 65. However, raising taxes on people making more than $400,000 a year to shore up Medicare’s finances is one idea that won strong backing in a recent poll by The Associated Press and NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Brian Blase, a former Trump health adviser and the president of Paragon Health Institute, said Republicans, if they win more control of the federal government, should seek to lower spending on Medicare Advantage — through which commercial insurers provide benefits — to build on the program’s efficiencies and ensure it costs taxpayers less than the traditional program.

So far, though, Republicans, including Trump, have expressed little interest in such a plan. Some of them are clear-eyed about the perils of running on changing Medicare, which cost $829 billion in 2021 and is projected to consume nearly 18% of the federal budget by 2032.

“It’s difficult to have a frank conversation with voters about the future of the Medicare program,” said Lewis, the GOP pollster. “More often than not, it backfires. That conversation will have to happen right after a major election.”

Addiction Crisis

Many Americans have been touched by the growing opioid epidemic, which killed more than 112,000 people in the United States in 2023 — more than gun deaths and road fatalities combined. Rural residents and white adults are among the hardest hit.

Federal health officials have cited drug overdose deaths as a primary cause of the recent drop in U.S. life expectancy.

Republicans cast addiction as largely a criminal matter, associating it closely with the migration crisis at the U.S. southern border that they blame on Biden. Democrats have sought more funding for treatment and prevention of substance use disorders.

“This affects the family, the neighborhood,” said Blendon, the public opinion researcher.

Billions of dollars have begun to flow to states and local governments from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers and retailers, raising questions about how to best spend that money. But it isn’t clear that the crisis, outside the context of immigration, will emerge as a campaign issue.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Stop Walking on Eggshells – by Randi Kreger & Paul Mason

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As you may gather from the title, the angle here is not “Borderline Personality Disorder is fine and dandy”, but nor is it something anyone chooses to have, and as such, importantly, this book’s advice is also not “and so you should immediately disown, divorce, defenestrate your partner”, either.

Rather, it has a balanced and compassionate approach that examines both the pitfalls and the possibilities, and provides the tools to make your relationship feel (and hopefully, actually be) safe for all concerned.

And yes, ending a relationship is always an option too, even if it can sometimes feel like it’s not, on account of how the relationships of people with BPD often have a lot of “near miss” situations, nearly ending but not quite, or (in the case of a partner who’s amenable to such), off-and-on relationships—either of which can make it seem like it’ll never truly be over.

First, though, the authors do look at a variety of ways of avoiding that outcome; making changes within oneself, setting boundaries and honing related skills, asserting your needs with confidence and clarity, and dealing with the lies, rumor-mongering, and accusations that often come with BPD. For that matter, the authors do also note that not all conflict is abuse (something that many forget), but on the flipside, how to tell when it actually is, too.

The style is very pop-science, light in tone albeit sometimes heavy in content.

Bottom line: if you or a loved one has BPD, or even just has a lot of the same symptoms as such, this book can be very helpful.

Click here to check out Stop Walking On Eggshells, and stop walking on eggshells!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Apples vs Carrots – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apples to carrots, we picked the carrots.

Why?

Both are sweet crunchy snacks, both rightly considered very healthy options, but one comes out clearly on top…

Both contain lots of antioxidants, albeit mostly different ones. They’re both good for this.

Looking at their macros, however, apples have more carbs while carrots have more fiber. The carb:fiber ratio in apples is already sufficient to make them very healthy, but carrots do win.

In the category of vitamins, carrots have many times more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, E, K, and choline. Apples are not higher in any vitamins.

In terms of minerals, carrots have a lot more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Apples are not higher in any minerals.

If “an apple a day keeps the doctor away”, what might a carrot a day do?

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Sugar: From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose C’s

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Which Magnesium? (And: When?)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Good morning! I have been waiting for this day to ask: the magnesium in my calcium supplement is neither of the two versions you mentioned in a recent email newsletter. Is this a good type of magnesium and is it efficiently bioavailable in this composition? I also take magnesium that says it is elemental (oxide, gluconate, and lactate). Are these absorbable and useful in these sources? I am not interested in taking things if they aren’t helping me or making me healthier. Thank you for your wonderful, informative newsletter. It’s so nice to get non-biased information❞

Thank you for the kind words! We certainly do our best.

For reference: the attached image showed a supplement containing “Magnesium (as Magnesium Oxide & AlgaeCal® l.superpositum)”

Also for reference: the two versions we compared head-to-head were these very good options:

Magnesium Glycinate vs Magnesium Citrate – Which is Healthier?

Let’s first borrow from the above, where we mentioned: magnesium oxide is probably the most widely-sold magnesium supplement because it’s cheapest to make. It also has woeful bioavailability, to the point that there seems to be negligible benefit to taking it. So we don’t recommend that.

As for magnesium gluconate and magnesium lactate:

- Magnesium lactate has very good bioavailability and in cases where people have problems with other types (e.g. gastrointestinal side effects), this will probably not trigger those.

- Magnesium gluconate has excellent bioavailability, probably coming second only to magnesium glycinate.

The “AlgaeCal® l.superpositum” supplement is a little opaque (and we did ntoice they didn’t specify what percentage of the magnesium is magnesium oxide, and what percentage is from the algae, meaning it could be a 99:1 ratio split, just so that they can claim it’s in there), but we can say Lithothamnion superpositum is indeed an algae and magnesium from green things is usually good.

Except…

It’s generally best not to take magnesium and calcium together (as that supplement contains). While they do work synergistically once absorbed, they compete for absorption first so it’s best to take them separately. Because of magnesium’s sleep-improving qualities, many people take calcium in the morning, and magnesium in the evening, for this reason.

Some previous articles you might enjoy meanwhile:

- Pinpointing The Usefulness Of Acupuncture

- Science-Based Alternative Pain Relief

- Peripheral Neuropathy: How To Avoid It, Manage It, Treat It

- What Does Lion’s Mane Actually Do, Anyway?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: