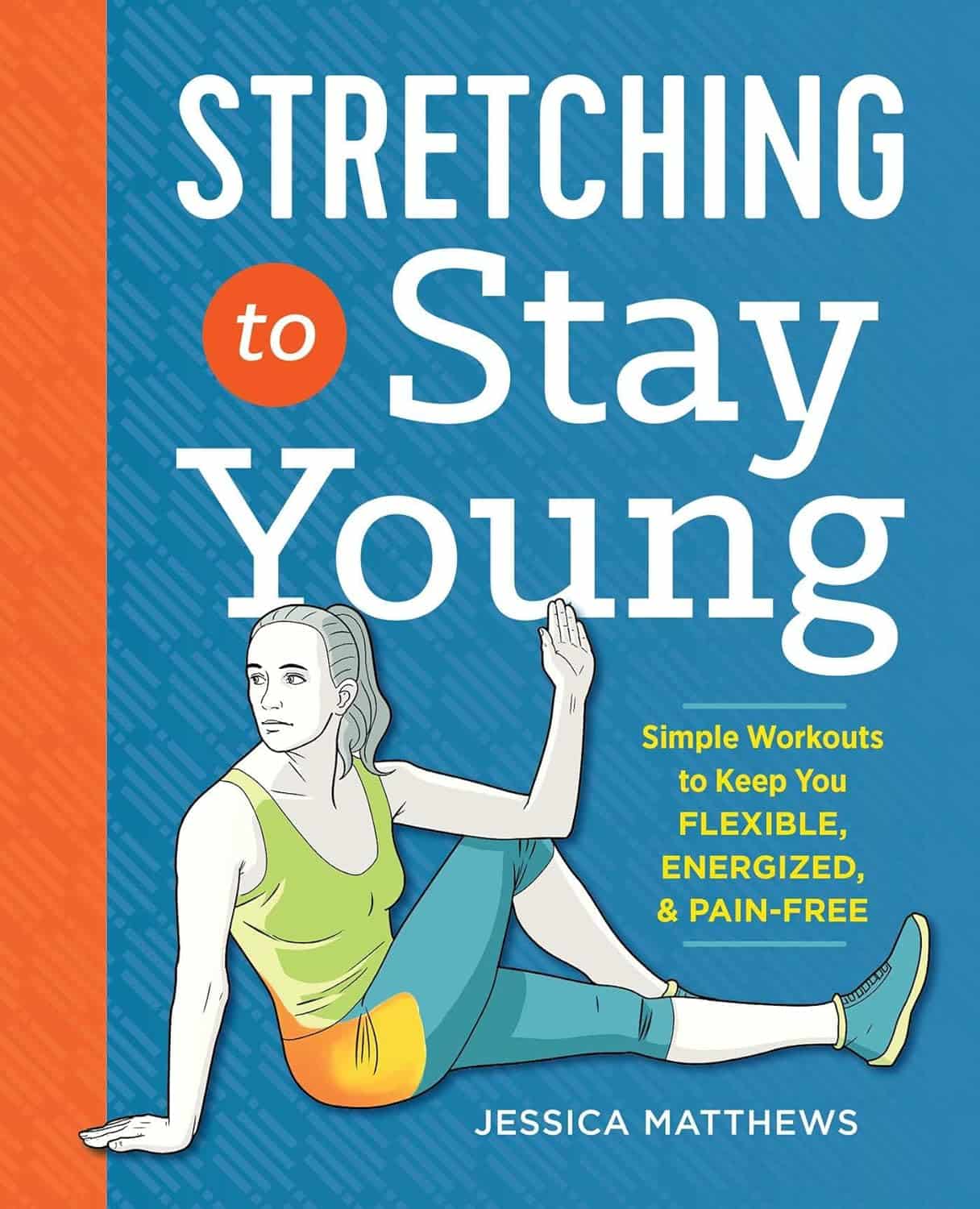

Stretching to Stay Young – by Jessica Matthews

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A lot of stretching gurus (especially the Instagrammable kind) offer advices like “if you can’t do the splits balanced between two chairs to start with, that’s fine… just practise by doing the splits against a wall first!”

Jessica Matthews, meanwhile, takes a more grounded approach. A lot of this is less like yoga and more like physiotherapy—it’s uncomplicated and functional. There’s nothing flashy here… just the promise of being able to thrive in your body; supple and comfortable, doing the activities that matter to you.

On which note: the book gives advices about stretches for before and after common activities, for example:

- a bedtime routine set

- a pre-gardening set

- a post-phonecall set

- a level-up-your golf set

- a get ready for dancing set

…and many more. Whether “your thing” is cross-country skiing or knitting, she’s got you covered.

The book covers the whole body from head to toe. Whether you want to be sure to stretch everything, or just work on a particular part of your body that needs special attention, it’s there… with beautifully clear illustrations (the front cover illustration is indicative of the style—note how the muscle being stretched is highlighted in orange, too) and simple, easy-to-understand instructions.

All in all, we’re none of us getting any younger, but we sure can take some of our youth into whatever years come next. This is the stuff that life is made of!

Get your copy of “Stretching To Stay Young” from Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Methods

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

This newsletter has been growing a lot lately, and so have the questions/requests, and we love that! In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

Q: I am now in the “aging” population. A great concern for me is Alzheimers. My father had it and I am so worried. What is the latest research on prevention?

Very important stuff! We wrote about this not long back:

- See: How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

- See also: Brain Food? The Eyes Have It!

(one good thing to note is that while Alzheimer’s has a genetic component, it doesn’t appear to be hereditary per se. Still, good to be on top of these things, and it’s never too early to start with preventive measures!)

Share This Post

-

Keep Your Wits About You – by Dr. Vonetta Dotson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Dotson sets out to provide the reader with the tools to maintain good brain health at any age, though she does assume the reader to be in midlife or older.

She talks us through the most important kinds of physical activity, mental activity, and social activity, as well as a good grounding in brain-healthy nutrition, and how to beat the often catch-22 situation of poor sleep.

If you are the sort of person who likes refreshers on what you have just read, you’ll enjoy that the final two chapters repeat the information from chapters 2–6. If not, then well, if you skip the final 2 chapters the book will be 25% shorter without loss of content.

The style is enthusiastic; when it comes to her passion for the brain, Dr. Dotson both tells and shows, in abundance. While some authors may take care to break down the information in a way that can be understood from skimming alone, Dr. Dotson assumes that the reader’s interest will match hers, and thus will not mind a lot of lengthy prose with in-line citations. So, provided that’s the way you like to read, it’ll suit you too.

Bottom line: if you are looking for a book on maintaining optimal brain health that covers the basics without adding advice that is out of the norm, then this is a fine option for that!

Click here to check out Keep Your Wits About You, and keep your wits about you!

Share This Post

-

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers – by Dr. Robert M. Sapolsky

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The book does kick off with a section that didn’t age well—he talks of the stress induced globally by the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, and how that kind of thing just doesn’t happen any more. Today, we have much less existentially dangerous stressors!

However, the fact we went and had another pandemic really only adds weight to the general arguments of the book, rather than detracting.

We are consistently beset by “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” as Shakespeare would put it, and there’s a reason (or twenty) why many people go grocery-shopping with the cortisol levels of someone being hunted for sport.

So, why don’t zebras get ulcers, as they actually are hunted for food?

They don’t have rent to pay or a mortgage, they don’t have taxes, or traffic, or a broken washing machine, or a project due in the morning. Their problems come one at a time. They have a useful stress response to a stressful situation (say, being chased by lions), and when the danger is over, they go back to grazing. They have time to recover.

For us, we are (usually) not being chased by lions. But we have everything else, constantly, around the clock. So, how to fix that?

Dr. Sapolsky comprehensively describes our physiological responses to stress in quite different terms than many. By reframing stress responses as part of the homeostatic system—trying to get the body back into balance—we find a solution, or rather: ways to help our bodies recover.

The style is “pop-science” and is very accessible for the lay reader while still clearly coming from a top-level academic who is neck-deep in neuroendocrinological research. Best of both worlds!

Bottom line: if you try to take very day at a time, but sometimes several days gang up on you at once, and you’d like to learn more about what happens inside you as a result and how to fix that, this book is for you!

Click here to check out “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers” and give yourself a break!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Getting Your Messy Life In Order

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Getting Your Messy Life In Order

We’ve touched on this before by recommending the book, but today we’re going to give an overview of the absolute most core essentials of the “Getting Things Done” method. If you’re unfamiliar, this will be enough to get you going. If you’re already familiar, this may be a handy reminder!

First, you’ll need:

- A big table

- A block of small memo paper squares—post-it note sized, but no need to be sticky.

- A block of A4 printer paper

- A big trash bag

Gathering everything

Gather up not just all your to-dos, but: all sources of to-dos, too, and anything else that otherwise needs “sorting”.

Put them all in one physical place—a dining room table may have enough room. You’ll need a lot of room because you’re going to empty our drawers of papers, unopened (or opened and set aside) mail. Little notes you made for yourself, things stuck on the fridge or memo boards. Think across all areas of your life, and anything you’re “supposed” to do, write it down on a piece of paper. No matter what area of your life, no matter how big or small.

Whether it’s “learn Chinese” or “take the trash out”, write it down, one item per piece of paper (hence the block of little memo squares).

Sorting everything

Everything you’ve gathered needs one of three things to happen:

- You need to take some action (put it in a “to do” pile)

- You may need it later sometime (put it in a “to file” pile)

- You don’t need it (put it in the big trash bag for disposal)

What happens next will soothe you

- Dispose of the things you put for disposal

- File the things for filing in a single alphabetical filing system. If you don’t have one, you’ll need to get one, so write that down and add it to the “to do” pile.

- You will now process your “to dos”

Processing the “to dos”

The pile you have left is now your “inbox”. It’s probably huge; later it’ll be smaller, maybe just a letter-tray on your desk.

Many of your “to dos” are actually not single action items, they’re projects. If something requires more than one step, it’s a project.

Take each item one-by-one. Do this in any order; you’re going to do this as quickly as possible! Now, ask yourself: is this a single-action item that I could do next, without having to do something else first?

- If yes: put it in a pile marked “next action”

- If no: put it in a pile marked “projects”.

Take a sheet of A4 paper and fold it in half. Write “Next Action” on it, and put your pile of next actions inside it.

Take a sheet of A4 paper per project and write the name of the project on it, for example “Learn Chinese”, or “Do taxes”. Put any actions relating to that project inside it.

Likely you don’t know yet what the first action will be, or else it’d be in your “Next Action” pile, so add an item to each project that says “Brainstorm project”.

Processing the “Next Action” pile

Again you want to do this as quickly as possible, in any order.

For each item, ask yourself “Do I care about this?” If the answer is no, ditch that item, and throw it out. That’s ok. Things change and maybe we no longer want or need to do something. No point in hanging onto it.

For each remaining item, ask yourself “can this be done in under 2 minutes?”.

- If yes, do it, now. Throw away the piece of paper for it when you’re done.

- If no, ask yourself:”could I usefully delegate this to someone else?” If the answer is yes, do so.

If you can’t delegate it, ask yourself: “When will be a good time to do this?” and schedule time for it. A specific, written-down, clock time on a specific calendar date. Input that into whatever you use for scheduling things. If you don’t already use something, just use the calendar app on whatever device you use most.

The mnemonic for the above process is “Do/Defer/Delegate/Ditch”

Processing projects:

If you don’t know where to start with a project, then figuring out where to start is your “Next Action” for that project. Brainstorm it, write down everything you’ll need to do, and anything that needs doing first.

The end result of this is:

- You will always, at any given time, have a complete (and accessible) view of everything you are “supposed” to do.

- You will always, at any given time, know what action you need to take next for a given project.

- You will always, when you designate “work time”, be able to get straight into a very efficient process of getting through your to-dos.

Keeping on top of things

- Whenever stuff “to do something with/about” comes to you, put it in your physical “inbox” place—as mentioned, a letter-tray on a desk should suffice.

- At the start of each working day, quickly process things as described above. This should be a small daily task.

- Once a week, do a weekly review to make sure you didn’t lose sight of something.

- Monthly, quarterly, and annual reviews can be a good practice too.

How to do those reviews? Topic for another day, perhaps.

Or:

Check out the website / Check out GTD apps / Check out the book

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is a ‘vaginal birth after caesarean’ or VBAC?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A vaginal birth after caesarean (known as a VBAC) is when a woman who has had a caesarean has a vaginal birth down the track.

In Australia, about 12% of women have a vaginal birth for a subsequent baby after a caesarean. A VBAC is much more common in some other countries, including in several Scandinavian ones, where 45-55% of women have one.

So what’s involved? What are the risks? And who’s most likely to give birth vaginally the next time round?

MVelishchuk/Shutterstock What happens? What are the risks?

When a woman chooses a VBAC she is cared for much like she would during a planned vaginal birth.

However, an induction of labour is avoided as much as possible, due to the slightly increased risk of the caesarean scar opening up (known as uterine rupture). This is because the medication used in inductions can stimulate strong contractions that put a greater strain on the scar.

In fact, one of the main reasons women may be recommended to have a repeat caesarean over a vaginal birth is due to an increased chance of her caesarean scar rupturing.

This is when layers of the uterus (womb) separate and an emergency caesarean is needed to deliver the baby and repair the uterus.

Uterine rupture is rare. It occurs in about 0.2-0.7% of women with a history of a previous caesarean. A uterine rupture can also happen without a previous caesarean, but this is even rarer.

However, uterine rupture is a medical emergency. A large European study found 13% of babies died after a uterine rupture and 10% of women needed to have their uterus removed.

The risk of uterine rupture increases if women have what’s known as complicated or classical caesarean scars, and for women who have had more than two previous caesareans.

Most care providers recommend you avoid getting pregnant again for around 12 months after a caesarean, to allow full healing of the scar and to reduce the risk of the scar rupturing.

National guidelines recommend women attempt a VBAC in hospital in case emergency care is needed after uterine rupture.

During a VBAC, recommendations are for closer monitoring of the baby’s heart rate and vigilance for abnormal pain that could indicate a rupture is happening.

If labour is not progressing, a caesarean would then usually be advised.

Giving birth in hospital is recommended for a vaginal birth after a caesarean. christinarosepix/Shutterstock Why avoid multiple caesareans?

There are also risks with repeat caesareans. These include slower recovery, increased risks of the placenta growing abnormally in subsequent pregnancies (placenta accreta), or low in front of the cervix (placenta praevia), and being readmitted to hospital for infection.

Women reported birth trauma and post-traumatic stress more commonly after a caesarean than a vaginal birth, especially if the caesarean was not planned.

Women who had a traumatic caesarean or disrespectful care in their previous birth may choose a VBAC to prevent re-traumatisation and to try to regain control over their birth.

We looked at what happened to women

The most common reason for a caesarean section in Australia is a repeat caesarean. Our new research looked at what this means for VBAC.

We analysed data about 172,000 low-risk women who gave birth for the first time in New South Wales between 2001 and 2016.

We found women who had an initial spontaneous vaginal birth had a 91.3% chance of having subsequent vaginal births. However, if they had a caesarean, their probability of having a VBAC was 4.6% after an elective caesarean and 9% after an emergency one.

We also confirmed what national data and previous studies have shown – there are lower VBAC rates (meaning higher rates of repeat caesareans) in private hospitals compared to public hospitals.

We found the probability of subsequent elective caesarean births was higher in private hospitals (84.9%) compared to public hospitals (76.9%).

Our study did not specifically address why this might be the case. However, we know that in private hospitals women access private obstetric care and experience higher caesarean rates overall.

What increases the chance of success?

When women plan a VBAC there is a 60-80% chance of having a vaginal birth in the next birth.

The success rates are higher for women who are younger, have a lower body mass index, have had a previous vaginal birth, give birth in a home-like environment or with midwife-led care.

For instance, an Australian study found women who accessed continuity of care with a midwife were more likely to have a successful VBAC compared to having no continuity of care and seeing different care providers each time.

An Australian national survey we conducted found having continuity of care with a midwife when planning a VBAC can increase women’s sense of control and confidence, increase their chance to be upright and active in labour and result in a better relationship with their health-care provider.

Seeing the same midwife throughout your maternity care can help. Tyler Olson/Shutterstock Why is this important?

With the rise of caesareans globally, including in Australia, it is more important than ever to value vaginal birth and support women to have a VBAC if this is what they choose.

Our research is also a reminder that how a woman gives birth the first time greatly influences how she gives birth after that. For too many women, this can lead to multiple caesareans, not all of them needed.

Hannah Dahlen, Professor of Midwifery, Associate Dean Research and HDR, Midwifery Discipline Leader, Western Sydney University; Hazel Keedle, Senior Lecturer of Midwifery, Western Sydney University, and Lilian Peters, Adjunct Research Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why do disinfectants only kill 99.9% of germs? Here’s the science

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have you ever wondered why most disinfectants indicate they kill 99.9% or 99.99% of germs, but never promise to wipe out all of them? Perhaps the thought has crossed your mind mid-way through cleaning your kitchen or bathroom.

Surely, in a world where science is able to do all sorts of amazing things, someone would have invented a disinfectant that is 100% effective?

The answer to this conundrum requires understanding a bit of microbiology and a bit of mathematics.

Davor Geber/Shutterstock What is a disinfectant?

A disinfectant is a substance used to kill or inactivate bacteria, viruses and other microbes on inanimate objects.

There are literally millions of microbes on surfaces and objects in our domestic environment. While most microbes are not harmful (and some are even good for us) a small proportion can make us sick.

Although disinfection can include physical interventions such as heat treatment or the use of UV light, typically when we think of disinfectants we are referring to the use of chemicals to kill microbes on surfaces or objects.

Chemical disinfectants often contain active ingredients such as alcohols, chlorine compounds and hydrogen peroxide which can target vital components of different microbes to kill them.

Diseinfectants can contain a range of ingredients. Maridav/Shutterstock The maths of microbial elimination

In the past few years we’ve all become familiar with the concept of exponential growth in the context of the spread of COVID cases.

This is where numbers grow at an ever-accelerating rate, which can lead to an explosion in the size of something very quickly. For example, if a colony of 100 bacteria doubles every hour, in 24 hours’ time the population of bacteria would be more than 1.5 billion.

Conversely, the killing or inactivating of microbes follows a logarithmic decay pattern, which is essentially the opposite of exponential growth. Here, while the number of microbes decreases over time, the rate of death becomes slower as the number of microbes becomes smaller.

For example, if a particular disinfectant kills 90% of bacteria every minute, after one minute, only 10% of the original bacteria will remain. After the next minute, 10% of that remaining 10% (or 1% of the original amount) will remain, and so on.

Because of this logarithmic decay pattern, it’s not possible to ever claim you can kill 100% of any microbial population. You can only ever scientifically say that you are able to reduce the microbial load by a proportion of the initial population. This is why most disinfectants sold for domestic use indicate they kill 99.9% of germs.

Other products such as hand sanitisers and disinfectant wipes, which also often purport to kill 99.9% of germs, follow the same principle.

You might have noticed none of the cleaning products in your laundry cupboard kill 100% of germs. Africa Studio/Shutterstock Real-world implications

As with a lot of science, things get a bit more complicated in the real world than they are in the laboratory. There are a number of other factors to consider when assessing how well a disinfectant is likely to remove microbes from a surface.

One of these factors is the size of the initial microbial population that you’re trying to get rid of. That is, the more contaminated a surface is, the harder the disinfectant needs to work to eliminate the microbes.

If for example you were to start off with only 100 microbes on a surface or object, and you removed 99.9% of these using a disinfectant, you could have a lot of confidence that you have effectively removed all the microbes from that surface or object (called sterilisation).

In contrast, if you have a large initial microbial population of hundreds of millions or billions of microbes contaminating a surface, even reducing the microbial load by 99.9% may still mean there are potentially millions of microbes remaining on the surface.

Time is is a key factor that determines how effectively microbes are killed. So exposing a highly contaminated surface to disinfectant for a longer period is one way to ensure you kill more of the microbial population.

This is why if you look closely at the labels of many common household disinfectants, they will often suggest that to disinfect you should apply the product then wait a specified time before wiping clean. So always consult the label on the product you’re using.

Disinfectants won’t necessarily work in your kitchen exactly like they work in a lab. Ground Picture/Shutterstock Other factors such as temperature, humidity and the type of surface also influence how well a disinfectant works outside the lab.

Similarly, microbes in the real world may be either more or less sensitive to disinfection than those used for testing in the lab.

Disinfectants are one part infection control

The sensible use of disinfectants plays an important role in our daily lives in reducing our exposure to pathogens (microbes that cause illness). They can therefore reduce our chances of getting sick.

The fact disinfectants can’t be shown to be 100% effective from a scientific perspective in no way detracts from their importance in infection control. But their use should always be complemented by other infection control practices, such as hand washing, to reduce the risk of infection.

Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, Epidemiology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: