Statins: His & Hers?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Hidden Complexities of Statins and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

This is Dr. Barbara Roberts. She’s a cardiologist and the Director of the Women’s Cardiac Center at one of the Brown University Medical School teaching hospitals. She’s an Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine and takes care of patients, teaches medical students, and does clinical research. She specializes in gender-specific aspects of heart disease, and in heart disease prevention.

We previously reviewed Dr. Barbara Roberts’ excellent book “The Truth About Statins: Risks and Alternatives to Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs”. It prompted some requests to do a main feature about Statins, so we’re doing it today. It’s under the auspices of “Expert Insights” as we’ll be drawing almost entirely from Dr. Roberts’ work.

So, what are the risks of statins?

According to Dr. Roberts, one of the biggest risks is not just drug side-effects or anything like that, but rather, what they simply won’t treat. This is because statins will lower LDL (bad) cholesterol levels, without necessarily treating the underlying cause.

Imagine you got Covid, and it’s one of the earlier strains that’s more likely deadly than “merely” debilitating.

You’re coughing and your throat feels like you gargled glass.

Your doctor gives you a miracle cough medicine that stops your coughing and makes your throat feel much better.

(Then a few weeks later, you die, because this did absolutely nothing for the underlying problem)

You see the problem?

Are there problematic side-effects too, though?

There can be. But of course, all drugs can have side effects! So that’s not necessarily news, but what’s relevant here is the kind of track these side-effects can lead one down.

For example, Dr. Roberts cites a case in which a woman’s LDL levels were high and she was prescribed simvastatin (Zocor), 20mg/day. Here’s what happened, in sequence:

- She started getting panic attacks. So, her doctor prescribed her sertraline (Zoloft) (a very common SSRI antidepressant) and when that didn’t fix it, paroxetine (Paxil). This didn’t work either… because the problem was not actually her mental health. The panic attacks got worse…

- Then, while exercising, she started noticing progressive arm and leg weakness. Her doctor finally took her off the simvastatin, and temporarily switched to ezetimibe (Zetia), a less powerful nonstatin drug that blocks cholesterol absorption, which change eased her arm and leg problem.

- As the Zetia was a stopgap measure, the doctor put her on atorvastatin (Lipitor). Now she got episodes of severe chest pressure, and a skyrocketing heart rate. She also got tremors and lost her body temperature regulation.

- So the doctor stopped the atorvastatin and tried rosovastatin (Crestor), on which she now suffered exhaustion (we’re not surprised, by this point) and muscle pains in her arms and chest.

- So the doctor stopped the rosovastatin and tried lovastatin (Mevacor), and now she had the same symptoms as before, plus light-headedness.

- So the doctor stopped the lovastatin and tried fluvastatin (Lescol). Same thing happened.

- So he stopped the fluvastatin and tried pravastatin (Pravachol), without improvement.

- So finally he took her off all these statins because the high LDL was less deleterious to her life than all these things.

- She did her own research, and went back to the doctor to ask for cholestyramine (Questran), which is a bile acid sequestrent and nothing to do with statins. She also asked for a long-acting niacin. In high doses, niacin (one of the B-vitamins) raises HDL (good) cholesterol, lowers LDL, and lowers tryglycerides.

- Her own non-statin self-prescription (with her doctor’s signature) worked, and she went back to her life, her work, and took up running.

Quite a treatment journey! Want to know more about the option that actually worked?

Read: Bile Acid Resins or Sequestrants

What are the gender differences you/she mentioned?

Actually mostly sex differences, since this appears to be hormonal (which means that if your hormones change, so will your risk). A lot of this is still pending more research—basically it’s a similar problem in heart disease to one we’ve previously talked about with regard to diabetes. Diabetes disproportionately affects black people, while diabetes research disproportionately focuses on white people.

In this case, most heart disease research has focused on men, with women often not merely going unresearched, but also often undiagnosed and untreated until it’s too late. And the treatments, if prescribed? Assumed to be the same as for men.

Dr. Roberts tells of how medicine is taught:

❝When I was in medical school, my professors took the “bikini approach” to women’s health: women’s health meant breasts and reproductive organs. Otherwise the prototypical patient was presented as a man.❞

There has been some research done with statins and women, though! Just, still not a lot. But we do know for example that some statins can be especially useful for treating women’s atherosclerosis—with a 50% success rate, rather than 31% for men.

For lowering LDL itself, however, it can work but is generally not so hot in women.

Fun fact:

In men:

- High total cholesterol

- High non-HDL cholesterol

- High LDL cholesterol

- Low HDL cholesterol

…are all significantly associated with an increased risk of death from CVD.

In women:

…levels of LDL cholesterol even more than 190 were associated with only a small, statistically insignificant increased risk of dying from CVD.

So…

The fact that women derive less benefit from a medicine that mainly lowers LDL cholesterol, may be because elevated LDL cholesterol is less harmful to women than it is to men.

And also: Treatment and Response to Statins: Gender-related Differences

And for that matter: Women Versus Men: Is There Equal Benefit and Safety from Statins?*

Definitely a case where Betteridge’s Law of Headlines applies!

What should women do to avoid dying of CVD, then?

First, quick reminder of our general disclaimer: we can’t give medical advice and nothing here comprises such. However… One particularly relevant thing we found illuminating in Dr. Roberts’ work was this observation:

The metabolic syndrome is diagnosed if you have three (or more) out of five of the following:

- Abdominal obesity (waist >35″ if a woman or >40″ if a man)

- Fasting blood sugars of 100mg/dl or more

- Fasting triglycerides of 150mg/dl or more

- Blood pressure of 130/85 or higher

- HDL <50 if a woman or <40 if a man

And yet… because these things can be addressed with exercise and a healthy diet, which neither pharmaceutical companies nor insurance companies have a particular stake in, there’s a lot of focus instead on LDL levels (since there are a flock of statins that can be sold be lower them)… Which, Dr. Roberts says, is not nearly as critical for women.

So women end up getting prescribed statins that cause panic attacks and all those things we mentioned earlier… To lower our LDL, which isn’t nearly as big a factor as the other things.

In summary:

Statins do have their place, especially for men. They can, however, mask underlying problems that need treatment—which becomes counterproductive.

When it comes to women, statins are—in broad terms—statistically not as good. They are a little more likely to be helpful specifically in cases of atherosclerosis, whereby they have a 50/50 chance of helping.

For women in particular, it may be worthwhile looking into alternative non-statin drugs, and, for everyone: diet and exercise.

Further reading: How Can I Safely Come Off Statins?

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is ‘doll therapy’ for people with dementia? And is it backed by science?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The way people living with dementia experience the world can change as the disease progresses. Their sense of reality or place in time can become distorted, which can cause agitation and distress.

One of the best ways to support people experiencing changes in perception and behaviour is to manage their environment. This can have profound benefits including reducing the need for sedatives.

One such strategy is the use of dolls as comfort aids.

Jack Cronkhite/Shutterstock What is ‘doll therapy’?

More appropriately referred to as “child representation”, lifelike dolls (also known as empathy dolls) can provide comfort for some people with dementia.

Memories from the distant past are often more salient than more recent events in dementia. This means that past experiences of parenthood and caring for young children may feel more “real” to a person with dementia than where they are now.

Hallucinations or delusions may also occur, where a person hears a baby crying or fears they have lost their baby.

Providing a doll can be a tangible way of reducing distress without invalidating the experience of the person with dementia.

Some people believe the doll is real

A recent case involving an aged care nurse mistreating a dementia patient’s therapy doll highlights the importance of appropriate training and support for care workers in this area.

For those who do become attached to a therapeutic doll, they will treat the doll as a real baby needing care and may therefore have a profound emotional response if the doll is mishandled.

It’s important to be guided by the person with dementia and only act as if it’s a real baby if the person themselves believes that is the case.

What does the evidence say about their use?

Evidence shows the use of empathy dolls may help reduce agitation and anxiety and improve overall quality of life in people living with dementia.

Child representation therapy falls under the banner of non-pharmacological approaches to dementia care. More specifically, the attachment to the doll may act as a form of reminiscence therapy, which involves using prompts to reconnect with past experiences.

Interacting with the dolls may also act as a form of sensory stimulation, where the person with dementia may gain comfort from touching and holding the doll. Sensory stimulation may support emotional well-being and aid commnication.

However, not all people living with dementia will respond to an empathy doll.

It depends on a person’s background. Shutterstock The introduction of a therapeutic doll needs to be done in conjunction with careful observation and consideration of the person’s background.

Empathy dolls may be inappropriate or less effective for those who have not previously cared for children or who may have experienced past birth trauma or the loss of a child.

Be guided by the person with dementia and how they respond to the doll.

Are there downsides?

The approach has attracted some controversy. It has been suggested that child representation therapy “infantilises” people living with dementia and may increase negative stigma.

Further, the attachment may become so strong that the person with dementia will become upset if someone else picks the doll up. This may create some difficulties in the presence of grandchildren or when cleaning the doll.

The introduction of child representation therapy may also require additional staff training and time. Non-pharmacological interventions such as child representation, however, have been shown to be cost-effective.

Could robots be the future?

The use of more interactive empathy dolls and pet-like robots is also gaining popularity.

While robots have been shown to be feasible and acceptable in dementia care, there remains some contention about their benefits.

While some studies have shown positive outcomes, including reduced agitation, others show no improvement in cognition, behaviour or quality of life among people with dementia.

Advances in artificial intelligence are also being used to help support people living with dementia and inform the community.

Viv and Friends, for example, are AI companions who appear on a screen and can interact with the person with dementia in real time. The AI character Viv has dementia and was co-created with women living with dementia using verbatim scripts of their words, insights and experiences. While Viv can share her experience of living with dementia, she can also be programmed to talk about common interests, such as gardening.

These companions are currently being trialled in some residential aged care facilities and to help educate people on the lived experience of dementia.

How should you respond to your loved one’s empathy doll?

While child representation can be a useful adjunct in dementia care, it requires sensitivity and appropriate consideration of the person’s needs.

People living with dementia may not perceive the social world the same way as a person without dementia. But a person living with dementia is not a child and should never be treated as one.

Ensure all family, friends and care workers are informed about the attachment to the empathy doll to help avoid unintentionally causing distress from inappropriate handling of the doll.

If using an interactive doll, ensure spare batteries are on hand.

Finally, it is important to reassess the attachment over time as the person’s response to the empathy doll may change.

Nikki-Anne Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Hardwiring Happiness – by Dr. Rick Hanson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Publishers are very excitable about “the new science of…”, and it’s almost never actually a new science of. But what about in this case?

No, it isn’t. It’s the very well established science of! And that’s a good thing, because it means this book is able to draw on quite a lot of research and established understanding of how neuroplasticity works, to leverage that and provide useful guidance.

A particular strength of this book is that while it polarizes the idea that some people have “happy amygdalae” and some people have “sad amygdalae”, it acknowledges that it’s not just a fated disposition and is rather the result of the lives people have led… And then provides advice on upgrading from sad to happy, based on the assumption that the reader is quite possibly coming from a non-ideal starting point.

The bookdoes an excellent job of straddling neuroscience and psychology, which sounds like not much of a straddle (the two are surely very connected, after all, right?) but this does mean that we’re hearing about the chemical structure of DNA inside the nuclei of the neurons of the insula, not long after reading an extended gardening metaphor about growth, choices, and vulnerabilities.

Bottom line: if you’d like a guide to changing your brain for the better (happier) that’s not just “ask yourself: what if it goes well?” and similar CBTisms, then this is a fine book for you.

Click here to check out Hardwiring Happiness, and indeed hardwire happiness!

Share This Post

-

Coffee & Your Gut

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Coffee, in moderation, is generally considered a healthful drink—speaking for the drink itself, at least! Because the same cannot be said for added sugar, various sorts of creamers, or iced caramelatte mocha frappucino dessert-style drinks:

The Bitter Truth About Coffee (or is it?)

Caffeine, too, broadly has more pros than cons (again, in moderation):

Caffeine: Cognitive Enhancer Or Brain-Wrecker?

Some people will be concerned about coffee and the heart. Assuming you don’t have a caffeine sensitivity (or you do but you drink decaf), it is heart-neutral in moderation, though there are some ways of preparing it that are better than others:

Make Your Coffee Heart-Healthier!

So, what about coffee and the gut?

The bacteria who enjoy a good coffee

Amongst our trillions of tiny friends, allies, associates, and enemies-on-the-inside, which ones like coffee, and what kind of coffee do they prefer?

A big (n=35,214) international multicohort analysis examined the associations between coffee consumption and very many different gut microbial species, and found:

115 species were positively associated with coffee consumption, mostly of the kind considered “friendly”, including ones often included in probiotic supplements, such as various Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species.

The kind that was most strongly associated with coffee consumption, however, was Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus, a helpful little beast who converts chlorogenic acid (one of the main polyphenols in coffee) into caffeic acid, quinic acid, and various other metabolites that we can use.

More specifically: moderate coffee-drinkers, defined as drinking 1–3 cups per day, enjoyed a 300–400% increase in L. asaccharolyticus, while high coffee-drinkers (no, not that kind of high), defined as drinking 4 or more cups of coffee per day, enjoyed a 400–800% increase, compared to “never/rarely” coffee-drinkers (defined as drinking 2 or fewer cups per month).

Click here to see more data from the study, in a helpful infographic

Things that did not affect the outcome:

- The coffee-making method—it seems the bacteria are not fussy in this regard, as espresso or brewed, and even instant, yielded the same gut microbiome benefits

- The caffeine content—as both caffeinated and decaffeinated yielded the same gut microbiome benefits

You can read the paper itself in full for here:

Want to enjoy coffee, but not keen on the effects of caffeine or the taste of decaffeinated?

Taking l-theanine alongside coffee flattens the curve of caffeine metabolism, and means one can get the benefits without unwanted jitteriness:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Eat To Beat Cancer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Controlling What We Can, To Avoid Cancer

Every time a cell in our body is replaced, there’s a chance it will be cancerous. Exactly what that chance is depends on very many factors. Some of them we can’t control; others, we can.

Diet is a critical, modifiable factor

We can’t choose, for example, our genes. We can, for the most part, choose our diet. Why “for the most part”?

- Some people live in a food desert (the Arctic Circle is a good example where food choices are limited by supply)

- Some people have dietary restrictions (whether by health condition e.g. allergy, intolerance, etc or by personal-but-unwavering choice, e.g. vegetarian, vegan, kosher, halal, etc)

But for most of us, most of the time, we have a good control over our diet, and so that’s an area we can and should focus on.

Choose your animal protein wisely

If you are vegan, you can skip this section. If you are not, then the short version is:

- Fish: almost certainly fine

- Poultry: the jury is out; data is leaning towards fine, though

- Red meat: significantly increased cancer risk

- Processed meat: significantly increased cancer risk

For more details (and a run-down on the science behind the above super-summarized version):

- Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy? ← A mythbuster article that outlines many health properties (good and bad) of animal products

- The Whys and Hows of Cutting Meats Out Of Your Diet ← A life-hack article about acting on that information

Skip The Ultra-Processed Foods

Ok, so this one’s probably not a shocker in its simplest form:

❝Studies are showing us is that not only do the ultraprocessed foods increase the risk of cancer, but that after a cancer diagnosis such foods increase the risk of dying❞

Source: Is there a connection between ultraprocessed food and cancer?

There’s an unfortunate implication here! If you took the previous advice to heart and cut out [at least some] meat, and/but then replaced that with ultra-processed synthetic meat, then this was not a great improvement in cancer risk terms.

Ultra-processed meat is worse than unprocessed, regardless of whether it was from an animal or was synthetic.

In other words: if you buy textured soy pieces (a common synthetic meat), it pays to look at the ingredients, because there’s a difference between:

- INGREDIENTS: SOY

- INGREDIENTS: Rehydrated Textured SOY Protein (52%), Water, Rapeseed Oil, SOY Protein Concentrate, Seasoning (SULPHITES) (Dextrose, Flavourings, Salt, Onion Powder, Food Starch Modified, Yeast Extract, Colour: Red Iron Oxide), SOY Leghemoglobin, Fortified WHEAT Flour (WHEAT Flour, Calcium Carbonate, Iron, Niacin, Thiamin), Bamboo Fibre, Methylcellulose, Tomato Purée, Salt, Raising Agent: Ammonium Carbonates

Now, most of those original base ingredients are/were harmless per se (as are/were the grapes in wine—before processing into alcohol), but it has clearly been processed to Hell and back to do all that.

Choose the one that just says “soy”. Or eat soybeans. Or other beans. Or lentils. Really there are a lot of options.

About soy, by the way…

There is (mostly in the US, mostly funded by the animal agriculture industry) a lot of fearmongering about soy. Which is ironic, given the amount of soy that is fed to livestock to be fed to humans, but it does bear addressing:

❝Soy foods are safe for all cancer patients and are an excellent source of plant protein. Studies show soy may improve survival after breast cancer❞

Source: Food risks and cancer: What to avoid

(obviously, if you have a soy allergy then you should not consume soy—for most people, the above advice stands, though)

Advanced Glycation End-Products

These (which are Very Bad™ for very many things, including cancer) occur specifically as a result of processing animal proteins and fats.

Note: not even necessarily ultra-processing, just processing can do it. But ultra-processing is worse. What’s the difference, you wonder?

The difference between “ultra-processed” and just “processed”:

- Your average hotdog has been ultra-processed. It’s not only usually been changed with many artificial additives, it’s also been through a series of processes (physical and chemical) and ends up bearing little relation to the creature it came from.

- Your bacon (that you bought fresh from your local butcher, not a supermarket brand of unknown provenance, and definitely not the kind that might come on the top of frozen supermarket pizza) has been processed. It’s undergone a couple of simple processes on its journey “from farm to table”. Remember also that when you cook it, that too is one more process (and one that results in a lot of AGEs).

Read more: What’s so bad about AGEs?

Note if you really don’t want to cut out certain foods, changing the way you cook them (i.e., the last process your food undergoes before you eat it) can also reduce AGES:

Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet

Get More Fiber

❝The American Institute for Cancer Research shows that for every 10-gram increase in fiber in the diet, you improve survival after cancer diagnosis by 13%❞

Source: Plant-based diet is encouraged for patients with cancer

Yes, that’s post-diagnosis, but as a general rule of thumb, what is good/bad for cancer when you have it is good/bad for cancer beforehand, too.

If you’re thinking that increasing your fiber intake means having to add bran to everything, happily there are better ways:

Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Ginkgo Biloba, For Memory And, Uh, What Else Again?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ginkgo biloba, for memory and, uh, what else again?

Ginkgo biloba extract has enjoyed use for thousands of years for an assortment of uses, and has made its way from Traditional Chinese Medicine, to the world supplement market at large. See:

Ginkgo biloba: A Treasure of Functional Phytochemicals with Multimedicinal Applications

But what does the science say about the specific claims?

Antioxidant & anti-inflammatory

We’re going to lump these two qualities together for examination, since one invariably leads to the other.

A quick note: things that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, often also help guard against cancer and aging. However, in this case, there are few good studies pertaining to anti-aging, and none that we could find pertaining to anti-cancer potential.

So, does it have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, first?

Yes, it has potent antioxidants that do fight inflammation; this is clear, from an abundance of in vitro and in vivo studies, including with human patients:

- Properties of Ginkgo biloba L.: incl. Antioxidant Characterization

- Anti-inflammatory effects of Ginkgo biloba extract against hippocampal neuronal injury

- Gingko biloba-derived lactone prevents osteoarthritis by activating anti-inflammatory signaling pathway

- The anti-inflammatory properties of Ginkgo biloba for the treatment of pulmonary diseases

In short: it helps, and there’s plenty of science for it.

What about anti-aging effects?

For this, there is science, but a lot of the science is not great. As one team of researchers concluded while doing a research review of their own:

❝Based on the reviewed information regarding EGb’s effects in vitro and in vivo, most have reported very positive outcomes with strong statistical analyses, indicating that EGb must have some sort of beneficial effect.

However, information from the reported clinical trials involving EGb are hardly conclusive since many do not include information such as the participant’s age and physical condition, drug doses administered, duration of drug administered as well as suitable control groups for comparison.

We therefore call on clinicians and clinician-scientists to establish a set of standard and reliable standard operating procedure for future clinical studies to properly evaluate EGb’s effects in the healthy and diseased person since it is highly possible it possesses beneficial effects.❞

Translation from sciencese: “These results are great, but come on, please, we are begging you to use more robust methodology”

If you’d like to read the review in question, here it is:

Advances in the Studies of Ginkgo Biloba Leaves Extract on Aging-Related Diseases

Does it have cognitive enhancement effects?

The claims here are generally that it helps:

- improve memory

- improve focus

- reduce cognitive decline

- reduce anxiety and depression

Let’s break these down:

Does it improve memory and cognition?

Ginkgo biloba was quite popular for memory 20+ years ago, and perhaps had an uptick in popularity in the wake of the 1999 movie “Analyze This” in which the protagonist psychiatrist mentions taking ginkgo biloba, because “it helps my memory, and I forget what else”.

Here are a couple of studies from not long after that:

- A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba in cognitively intact older adults: neuropsychological findings

- Effects of Ginkgo biloba on mental functioning in healthy volunteers

In short:

- in the first study, it helped in standardized tests of memory and cognition (quite convincing)

- In the second study, it helped in subjective self-reports of mental wellness (also placebo-controlled)

On the other hand, here’s a more recent research review ten years later, that provides measures of memory, executive function and attention in 1132, 534 and 910 participants, respectively. That’s quite a few times more than the individual studies we cited above, by the way. They concluded:

❝We report that G. biloba had no ascertainable positive effects on a range of targeted cognitive functions in healthy individuals❞

Read: Is Ginkgo biloba a cognitive enhancer in healthy individuals? A meta-analysis

Our (10almonds) conclusion: we can’t say either way, on this one.

Does it have neuroprotective effects (i.e., against cognitive decline)?

Yes—probably by the same mechanism will discuss shortly.

- Ginkgo Biloba for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

- Treatment effects of Ginkgo biloba extract on symptoms of dementia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Can it help against depression and anxiety?

Yes—but probably indirectly by the mechanism we’ll get to in a moment:

- Role of Ginkgo biloba extract as an adjunctive treatment of elderly patients with depression

- Ginkgo biloba in generalized anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder with anxious mood

Likely this helps by improving blood flow, as illustrated better per:

Efficacy of ginkgo biloba extract as augmentation of venlafaxine in treating post-stroke depression

Which means…

Bonus: improved blood flow

This mechanism may support the other beneficial effects.

See: Ginkgo biloba extract improves coronary blood flow in healthy elderly adults

Is it safe?

Ginkgo biloba extract* is generally recognized as safe.

- However, as it improves blood flow, please don’t take it if you have a bleeding disorder.

- Additionally, it may interact badly with SSRIs, so you might want to avoid it if you’re taking such (despite it having been tested and found beneficial as an adjuvant to citalopram, an SSRI, in one of the studies above).

- No list of possible contraindications can be exhaustive, so please consult your own doctor/pharmacist before taking something new.

*Extract, specifically. The seeds and leaves of this plant are poisonous. Sometimes “all natural” is not better.

Where can I get it?

As ever, we don’t sell it (or anything else), but here’s an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

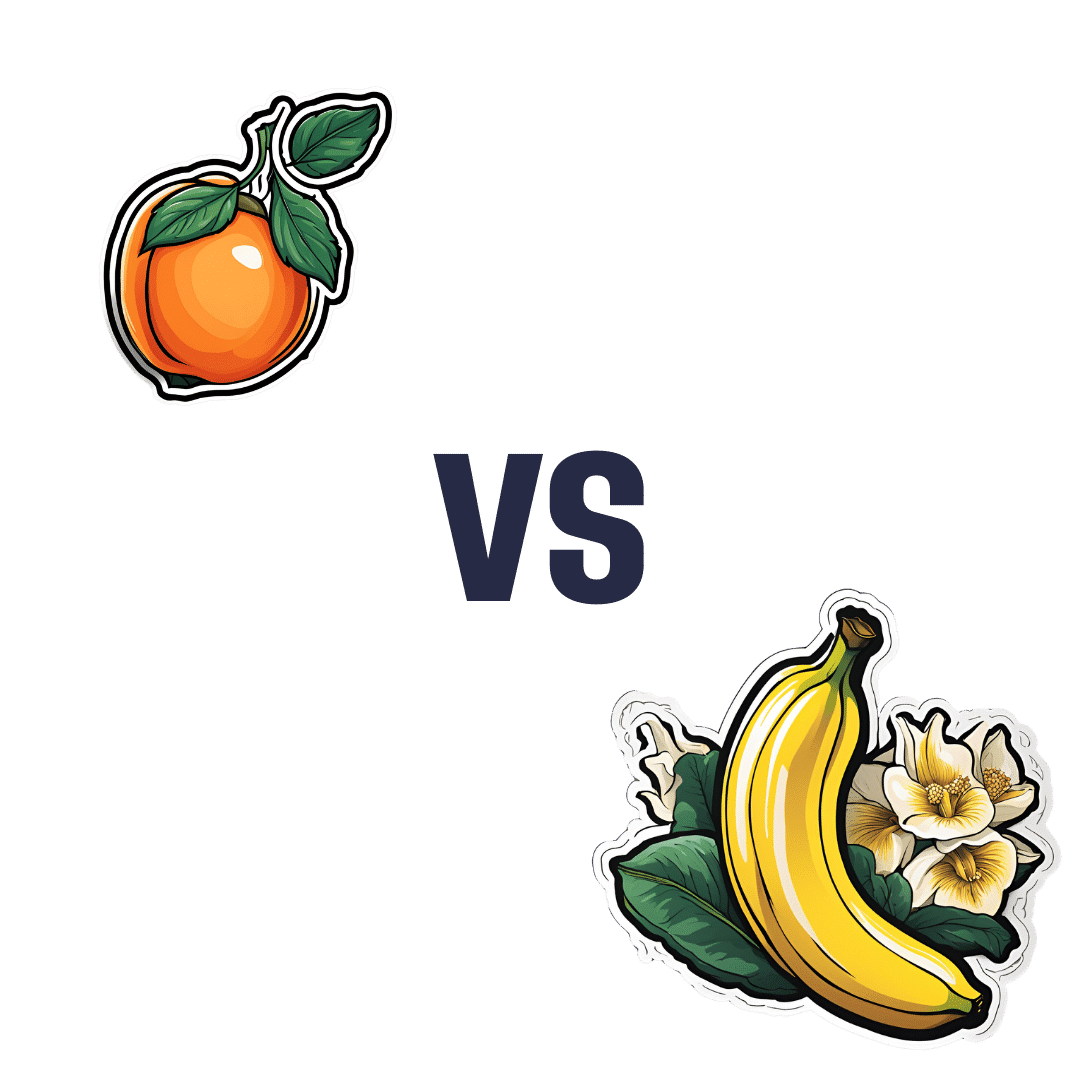

Apricot vs Banana – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apricot to banana, we picked the banana.

Why?

Both are great, and it was close!

In terms of macros, apricot has more protein, while banana has more carbs and fiber; both are low glycemic index foods, and we’ll call this category a tie.

In the category of vitamins, apricot has more of vitamins A, C, E, and K, while banana has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, and choline, giving banana the win by strength of numbers. It’s worth noting though that apricots are one of the best fruits for vitamin A in particular.

When it comes to minerals, apricot has slightly more calcium, iron, and zinc, while banana has a lot more magnesium, manganese, potassium, and selenium, meaning a moderate win for banana here.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for banana—but of course, by all means enjoy either or both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer ← we argue for apricots as bonus number 9 on the list

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: