How To Stop Binge-Eating: Flip This Switch!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“The Big Eating Therapist” Sarah Dosanjh has insights from both personal and professional experience:

No “Tough Love” Necessary

Eating certain foods is often socially shamed, and it’s easy to internalize that, and feel guilty. While often guilt is considered a pro-social emotion that helps people to avoid erring in a way that will get us excluded from the tribe (bearing in mind that for most of our evolutionary history, exile would mean near-certain death), it is not good at behavior modification when it comes to addictions or anything similar to addictions.

The reason for this is that if we indulge in a pleasure we feel we “shouldn’t” and expect we’d be shamed for, we then feel bad, and we immediately want something to make us feel better. Guess what that something will be. That’s right: the very same thing we literally just felt ashamed about.

So guilt is not helpful when it comes to (for example) avoiding binge-eating.

Instead, Dosanjh points us to a study whereby dieters ate a donut and drank water, before being given candy for taste testing. The control group proceeded without intervention, while the experimental group had a self-compassion intervention between the donut and the candy. This meant that researchers told the participants not to feel bad about eating the donut, emphasizing self-kindness, mindfulness, and common humanity. The study found that those who received the intervention, ate significantly less candy.

What we can learn from this is: we must be kind to ourselves. Allowing ourselves, consciously and mindfully, “a little treat”, secures its status as being “little”, and “a treat”. Then we smile, thinking “yes, that was a nice little thing to do for myself”, and proceed with our day.

This kind of self-compassion helps avoid the “meta-binge” process, where guilt from one thing leads to immediately reaching for another.

For more on this, plus a link to the study she mentioned, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Singledom & Healthy Longevity

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Statistically, those who live longest, do so in happy, fulfilling, committed relationships.

Note: happy, fulfilling, committed relationships. Less than that won’t do. Your insurance company might care about your marital status for its own sake, but your actual health doesn’t—it’s about the emotional safety and security that a good, healthy, happy, fulfilling relationship offers.

We wrote about this here:

Only One Kind Of Relationship Promotes Longevity This Much!

But that’s not the full story

For a start, while being in a happy fulfilling committed relationship statistically adds healthy life years, being in a relationship that falls short of those adjectives certainly does not. See also:

Relationships: When To Stick It Out & When To Call It Quits

But also, life satisfaction steadily improves with age, for single people (the results are more complicated for partnered people—probably because of the range of difference in quality of relationships). At least, this held true in this large (n=6,188) study of people aged 40–85 years:

❝With advancing age, partnership status became less predictive of loneliness and the satisfaction with being single increased. Among later-born cohorts, the association between partnership status and loneliness was less strong than among earlier-born cohorts. Later-born single people were more satisfied with being single than their earlier-born counterparts.❞

Note that this does mean that while life satisfaction indeed improves with age for single people, that’s a generalized trend, and the greatest life satisfaction within this set of singles comes hand-in-hand with being single by choice rather than by perceived obligation, i.e., those who are “single and not looking” will generally be the most content, and this contentedness will improve with age, but for those who are “single and looking”, in that case it’s the younger people who have it better, likely due to a greater sense of having plenty of time.

For that matter, gender plays a role; this large survey of singles found that (despite the popular old pop-up ads advising that “older women in your area are looking to date”), in reality older single women were the least likely to actively look for a partner:

See: A Profile Of Single Americans

…which also shows that about half of single Americans are “not looking”, and of those who are, about half are open to a serious relationship, though this is more common under the age of 40, while being over the age of 40 sees more people looking only for something casual.

Take-away from this section: being single only decreases life satisfaction if one doesn’t enjoy being single, and even then, and increases it if one does enjoy being single.

But that’s about life satisfaction, not longevity

We found no studies specifically into longevity of singledom, only the implications that may be drawn from the longevity of partnered people.

However, there is a lot of research that shows it’s not being single that kills, it’s being socially isolated. It’s a function of neurodegeneration from a lack of conversation, and it’s a function of what happens when someone slips in the shower and is found a week later. Things like that.

For example: Is Living Alone “Aging Alone”? Solitary Living, Network Types, and Well-Being

What if you are alone and don’t want to be?

We’ve not, at time of writing, written dating advice in our Psychology Sunday section, but this writer’s advice is: don’t even try.

That’s not nihilism or even cynicism, by the way; it’s actually a kind of optimism. The trick is just to let them come to you.

(sample size of one here, but this writer has never looked for a relationship in her life, they’ve always just found me, and now that I’m widowed and intend to remain single, I still get offers—and no, I’m not a supermodel, nor rich, nor anything like that)

Simply: instead of trying to find a partner, just work on expanding your social relationships in general (which is much easier, because the process is something you can control, whereas the outcome of trying to find a suitable partner is not), and if someone who’s right for you comes along, great! If not, then well, at least you have a flock of friends now, and who knows what new unexpected romance may lie around the corner.

As for how to do that,

How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Let’s Get Fruity

Bromelain is an enzyme* found in pineapple (and only in pineapple), that has many very healthful properties, some of them unique to bromelain.

*actually a combination of enzymes, but most often referred to collectively in the singular. But when you do see it referred to as “they”, that’s what that means.

What does it do?

It does a lot of things, for starters:

❝Various in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that they are anti-edematous, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancerous, anti-thrombotic, fibrinolytic, and facilitate the death of apoptotic cells. The pharmacological properties of bromelain are, in part, related to its arachidonate cascade modulation, inhibition of platelet aggregation, such as interference with malignant cell growth; anti-inflammatory action; fibrinolytic activity; skin debridement properties, and reduction of the severe effects of SARS-Cov-2❞

Some quick notes:

- “facilitate the death of apoptotic cells” may sound alarming, but it’s actually good; those cells need to be killed quickly; see for example: Fisetin: The Anti-Aging Assassin

- If you’re wondering what arachidonate cascade modulation means, that’s the modulation of the cascade reaction of arachidonic acid, which plays a part in providing energy for body functions, and has a role in cell structure formation, and is the precursor of assorted inflammatory mediators and cell-signalling chemicals.

- Its skin debridement properties (getting rid of dead skin) are most clearly seen when using bromelain topically (one can literally just make a pineapple poultice), but do occur from ingestion also (because of what it can do from the inside).

- As for being anti-thrombotic and fibrinolytic, let’s touch on that before we get to the main item, its anti-inflammatory properties.

If you want to read more of the above before moving on, though, here’s the full text:

Anti-thrombotic and fibrinolytic

While it does have anti-thrombotic effects, largely by its fibrinolytic action (i.e., it dissolves the fibrin mesh holding clots together), it can have a paradoxically beneficial effect on wound healing, too:

For more specifically on its wound-healing benefits:

In Vitro Effect of Bromelain on the Regenerative Properties of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Anti-inflammatory

Bromelain is perhaps most well-known for its anti-inflammatory powers, which are so diverse that it can be a challenge to pin them all down, as it has many mechanisms of action, and there’s a large heterogeneity of studies because it’s often studied in the context of specific diseases. But, for example:

❝Bromelain reduced IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α secretion when immune cells were already stimulated in an overproduction condition by proinflammatory cytokines, generating a modulation in the inflammatory response through prostaglandins reduction and activation of cascade reactions that trigger neutrophils and macrophages, in addition to accelerating the healing process❞

~ Dr. Taline Alves Nobre et al.

Read in full:

Bromelain as a natural anti-inflammatory drug: a systematic review

Or if you want a more specific example, here’s how it stacks up against arthritis:

❝The results demonstrated the chondroprotective effects of bromelain on cartilage degradation and the downregulation of inflammatory cytokine (tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) expression in TNF-α–induced synovial fibroblasts by suppressing NF-κB and MAPK signaling❞

~ Dr. Perephan Pothacharoen et al.

Read in full:

More?

Yes more! You’ll remember from the first paper we quoted today, that it has a long laundry list of benefits. However, there’s only so much we can cover in one edition, so that’s it for today

Is it safe?

It is generally recognized as safe. However, its blood-thinning effect means it should be avoided if you’re already on blood-thinners, have some sort of bleeding disorder, or are about to have a surgery.

Additionally, if you have a pineapple allergy, this one may not be for you.

Aside from that, anything can have drug interactions, so do check with your doctor/pharmacist to be sure (with the pharmacist usually being the more knowledgeable of the two, when it comes to drug interactions).

Want to try some?

You can just eat pineapples, but if you don’t enjoy that and/or wouldn’t want it every day, bromelain is available in supplement form too.

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

The Truth About Vaccines

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Truth About Vaccines

Yesterday we asked your views on vaccines, and we got an interesting spread of answers. Of those who responded to the poll, most were in favour of vaccines. We got quite a lot of comments this time too; we can’t feature them all, but we’ll include extracts from a few in our article today, as they raised interesting points!

Vaccines contain dangerous ingredients that will harm us more than the disease would: True or False?

False, contextually.

Many people are very understandably wary of things they know full well to be toxic, being injected into them.

One subscriber who voted for “Vaccines are poison, and/or are some manner of conspiracy ” wrote:

❝I think vaccines from 50–60 years ago are true vaccines and were safer than vaccines today. I have not had a vaccine for many, many years, and I never plan to have any kind of vaccine/shot again.❞

They didn’t say why they personally felt this way, but the notion that “things were simpler back in the day” is a common (and often correct!) observation regards health, especially when it comes to unwanted additives and ultraprocessing of food.

Things like aluminum or mercury in vaccines are much like sodium and chlorine in table salt. Sodium and chlorine are indeed both toxic to us. But in the form of sodium chloride, it’s a normal part of our diet, provided we don’t overdo it.

Additionally, the amount of unwanted metals (e.g. aluminum, mercury) in vaccines is orders of magnitude smaller than the amount in dietary sources—even if you’re a baby and your “dietary sources” are breast milk and/or formula milk.

In the case of formaldehyde (an inactivating agent), it’s also the dose that makes the poison (and the quantity in vaccines is truly miniscule).

This academic paper alone cites more sources than we could here without making today’s newsletter longer than it already is:

Vaccine Safety: Myths and Misinformation

I have a perfectly good immune system, it can handle the disease: True or False?

True! Contingently.

In fact, our immune system is so good at defending against disease, that the best thing we can do to protect ourselves is show our immune system a dead or deactivated version of a pathogen, so that when the real pathogen comes along, our immune system knows exactly what it is and what to do about it.

In other words, a vaccine.

One subscriber who voted for “Vaccines are important but in some cases the side effects can be worse ” wrote:

❝In some ways I’m vacd out. I got COVid a few months ago and had no symptoms except a cough. I have asthma and it didn’t trigger a lot of congestion. No issues. I am fully vaccinated but not sure I’ll get one in fall.❞

We’re glad this subscriber didn’t get too ill! A testimony to their robust immune system doing what it’s supposed to, after being shown a recent-ish edition of the pathogen, in deactivated form.

It’s very reasonable to start wondering: “surely I’m vaccinated enough by now”

And, hopefully, you are! But, as any given pathogen mutates over time, we eventually need to show our immune system what the new version looks like, or else it won’t recognize it.

See also: Why Experts Think You’ll Need a COVID-19 Booster Shot in the Future

So why don’t we need booster shots for everything? Often, it’s because a pathogen has stopped mutating at any meaningful rate. Polio is an example of this—no booster is needed for most people in most places.

Others, like flu, require annual boosters to keep up with the pathogens.

Herd immunity will keep us safe: True or False?

True! Ish.

But it doesn’t mean what a lot of people think it means. For example, in the UK, “herd immunity” was the strategy promoted by Prime Minister of the hour, Boris Johnson. But he misunderstood what it meant:

- What he thought it meant: everyone gets the disease, then everyone who doesn’t die is now immune

- What it actually means: if most people are immune to the disease (for example: due to having been vaccinated), it can’t easily get to the people who aren’t immune

One subscriber who voted for “Vaccines are critical for our health; vax to the max! ” wrote:

❝I had a chiropractor a few years ago, who explained to me that if the general public took vaccines, then she would not have to vaccinate her children and take a risk of having side effects❞

Obviously, we can’t speak for this subscriber’s chiropractor’s children, but this raises a good example: some people can’t safely have a given vaccine, due to underlying medical conditions—or perhaps it is not available to them, for example if they are under a certain age.

In such cases, herd immunity—other people around having been vaccinated and thus not passing on the disease—is what will keep them safe.

Here’s a useful guide from the US Dept of Health and Human Services:

How does community immunity (a.k.a. herd immunity) work?

And, for those who are more visually inclined, here’s a graphical representation of a mathematical model of how herd immunity works (you can run a simulation)!

Stay safe!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

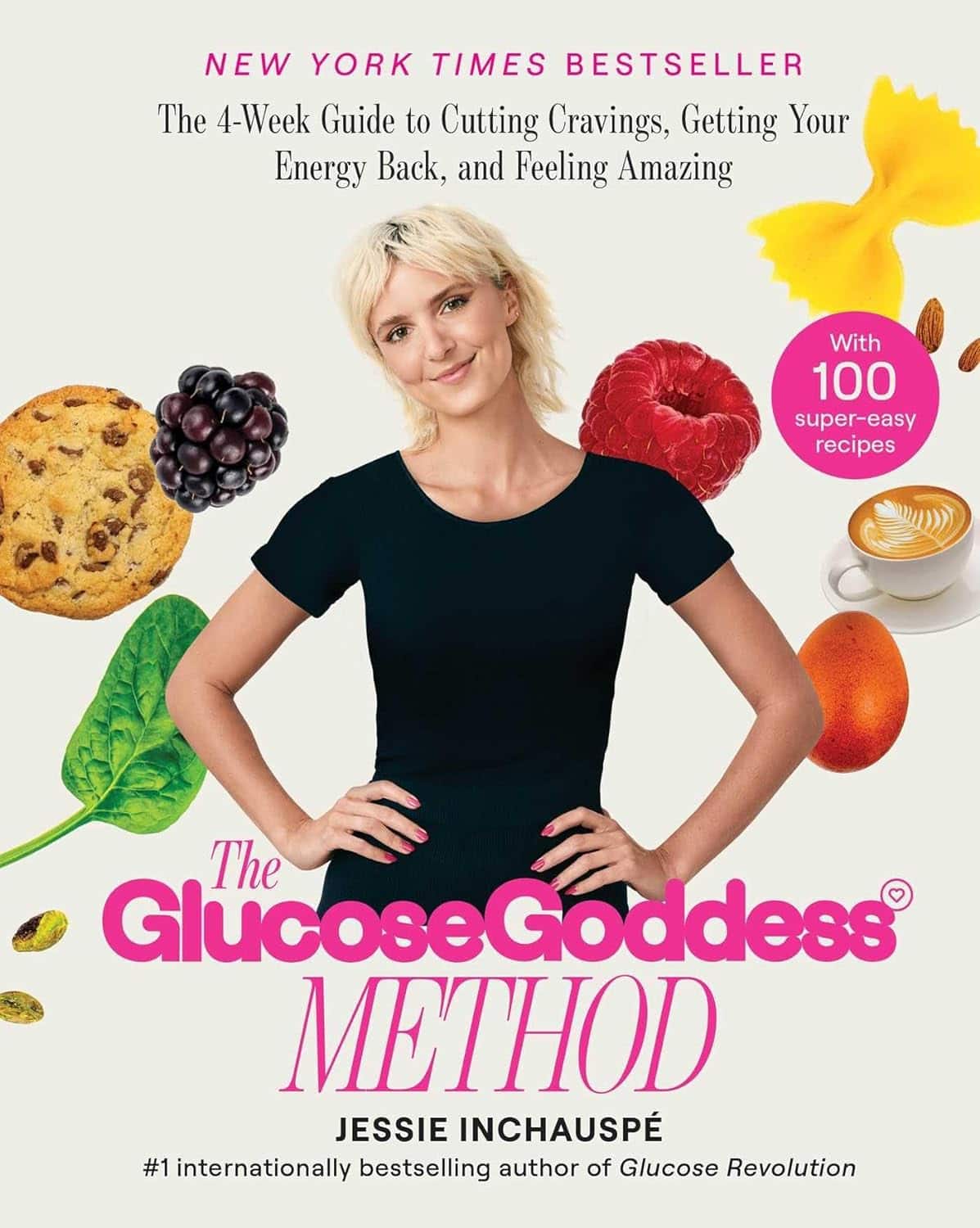

The Glucose Goddess Method – by Jessie Inchausspé

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Inchausspé’s excellent book “Glucose Revolution”. So what does this book add?

This book is for those who found that book a little dense. While this one still gives the same ten “hacks”, she focuses on the four that have the biggest effect, and walks the reader by the hand through a four-week programme of implementing them.

The claim of 100+ recipes is a little bold, as some of the recipes are things like vinegar, vinegar+water, vinegar+water but now we’re it’s in a restaurant, lemon+water, lemon+water but now it’s in a bottle, etc. However, there are legitimately a lot of actual recipes too.

Where this book’s greatest strength lies is in making everything super easy, and motivating. It’s a fine choice for being up-and-running quickly and easily without wading through the 300-odd pages of science in her previous book.

Bottom line: if you’ve already happily and sustainably implemented everything from her previous book, you can probably skip this one. However, if you’d like an easier method to implement the changes that have the biggest effect, then this is the book for you.

Click here to check out The Glucose Goddess Method, and build it into your life the easy way!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Constipation increases your risk of a heart attack, new study finds – and not just on the toilet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you Google the terms “constipation” and “heart attack” it’s not long before the name Elvis Presley crops up. Elvis had a longstanding history of chronic constipation and it’s believed he was straining very hard to poo, which then led to a fatal heart attack.

We don’t know what really happened to the so-called King of Rock “n” Roll back in 1977. There were likely several contributing factors to his death, and this theory is one of many.

But after this famous case researchers took a strong interest in the link between constipation and the risk of a heart attack.

This includes a recent study led by Australian researchers involving data from thousands of people.

Elvis Presley was said to have died of a heart attack while straining on the toilet. But is that true? Kraft74/Shutterstock Are constipation and heart attacks linked?

Large population studies show constipation is linked to an increased risk of heart attacks.

For example, an Australian study involved more than 540,000 people over 60 in hospital for a range of conditions. It found constipated patients had a higher risk of high blood pressure, heart attacks and strokes compared to non-constipated patients of the same age.

A Danish study of more than 900,000 people from hospitals and hospital outpatient clinics also found that people who were constipated had an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes.

It was unclear, however, if this relationship between constipation and an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes would hold true for healthy people outside hospital.

These Australian and Danish studies also did not factor in the effects of drugs used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension), which can make you constipated.

Researchers have studied thousands of people to see if there’s a link between constipation and heart attacks. fongbeerredhot/Shutterstock How about this new study?

The recent international study led by Monash University researchers found a connection between constipation and an increased risk of heart attacks, strokes and heart failure in a general population.

The researchers analysed data from the UK Biobank, a database of health-related information from about half a million people in the United Kingdom.

The researchers identified more than 23,000 cases of constipation and accounted for the effect of drugs to treat high blood pressure, which can lead to constipation.

People with constipation (identified through medical records or via a questionnaire) were twice as likely to have a heart attack, stroke or heart failure as those without constipation.

The researchers found a strong link between high blood pressure and constipation. Individuals with hypertension who were also constipated had a 34% increased risk of a major heart event compared to those with just hypertension.

The study only looked at the data from people of European ancestry. However, there is good reason to believe the link between constipation and heart attacks applies to other populations.

A Japanese study looked at more than 45,000 men and women in the general population. It found people passing a bowel motion once every two to three days had a higher risk of dying from heart disease compared with ones who passed at least one bowel motion a day.

How might constipation cause a heart attack?

Chronic constipation can lead to straining when passing a stool. This can result in laboured breathing and can lead to a rise in blood pressure.

In one Japanese study including ten elderly people, blood pressure was high just before passing a bowel motion and continued to rise during the bowel motion. This increase in blood pressure lasted for an hour afterwards, a pattern not seen in younger Japanese people.

One theory is that older people have stiffer blood vessels due to atherosclerosis (thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a build-up of plaque) and other age-related changes. So their high blood pressure can persist for some time after straining. But the blood pressure of younger people returns quickly to normal as they have more elastic blood vessels.

As blood pressure rises, the risk of heart disease increases. The risk of developing heart disease doubles when systolic blood pressure (the top number in your blood pressure reading) rises permanently by 20 mmHg (millimetres of mercury, a standard measure of blood pressure).

The systolic blood pressure rise with straining in passing a stool has been reported to be as high as 70 mmHg. This rise is only temporary but with persistent straining in chronic constipation this could lead to an increased risk of heart attacks.

High blood pressure from straining on the toilet can last after pooing, especially in older people. Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock Some people with chronic constipation may have an impaired function of their vagus nerve, which controls various bodily functions, including digestion, heart rate and breathing.

This impaired function can result in abnormalities of heart rate and over-activation of the flight-fight response. This can, in turn, lead to elevated blood pressure.

Another intriguing avenue of research examines the imbalance in gut bacteria in people with constipation.

This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, can result in microbes and other substances leaking through the gut barrier into the bloodstream and triggering an immune response. This, in turn, can lead to low-grade inflammation in the blood circulation and arteries becoming stiffer, increasing the risk of a heart attack.

This latest study also explored genetic links between constipation and heart disease. The researchers found shared genetic factors that underlie both constipation and heart disease.

What can we do about this?

Constipation affects around 19% of the global population aged 60 and older. So there is a substantial portion of the population at an increased risk of heart disease due to their bowel health.

Managing chronic constipation through dietary changes (particularly increased dietary fibre), increased physical activity, ensuring adequate hydration and using medications, if necessary, are all important ways to help improve bowel function and reduce the risk of heart disease.

Vincent Ho, Associate Professor and clinical academic gastroenterologist, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Apple Cider Vinegar vs Balsamic Vinegar – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apple cider vinegar to balsamic vinegar, we picked the apple cider vinegar.

Why?

It’s close! And it’s a simple one today and they’re both great. Taking either for blood-sugar-balancing benefits is fine, as it’s the acidity that has this effect. But:

- Of the two, balsamic vinegar is the one more likely to contain more sugars, especially if it’s been treated in any fashion, and not by you, e.g. made into a glaze or even a reduction (the latter has no need to add sugar, but sometimes companies do because it is cheaper—so we recommend making your own balsamic vinegar reduction at home)

- Of the two, apple cider vinegar is the one more likely to contain “the mother”, that is to say, the part with extra probiotic benefits (but if the vinegar has been filtered, it won’t have this—it’s just more common to be able to find unfiltered apple cider vinegar, since it has more popular attention for its health benefits than balsamic vinegar does)

So, two wins for apple cider vinegar there.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- 10 Ways To Balance Your Blood Sugars

- An Apple (Cider Vinegar) A Day…

- Apple Cider Vinegar vs Apple Cider Vinegar Gummies – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: