Hormones & Health, Beyond The Obvious

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Wholesome Health

This is Dr. Sara Gottfried, who some decades ago got her MD from Harvard and specialized as an OB/GYN at MIT. She’s since then spent the more recent part of her career educating people (mostly: women) about hormonal health, precision, functional, & integrative medicine, and the importance of lifestyle medicine in general.

What does she want us to know?

Beyond “bikini zone health”

Dr. Gottfried urges us to pay attention to our whole health, in context.

“Women’s health” is often thought of as what lies beneath a bikini, and if it’s not in those places, then we can basically treat a woman like a man.

And that’s often not actually true—because hormones affect every living cell in our body, and as a result, while prepubescent girls and postmenopausal women (specifically, those who are not on HRT) may share a few more similarities with boys and men of similar respective ages, for most people at most ages, men and women are by default quite different metabolically—which is what counts for a lot of diseases! And note, that difference is not just “faster” or “slower””, but is often very different in manner also.

That’s why, even in cases where incidence of disease is approximately similar in men and women when other factors are controlled for (age, lifestyle, medical history, etc), the disease course and response to treatment may vary considerable. For a strong example of this, see for example:

- The well-known: Heart Attack: His & Hers ← most people know these differences exist, but it’s always good to brush up on what they actually are

- The less-known: Statins: His & Hers ← most people don’t know these differences exist, and it pays to know, especially if you are a woman or care about one

Nor are brains exempt from his…

The female brain (kinda)

While the notion of an anatomically different brain for men and women has long since been thrown out as unscientific phrenology, and the idea of a genetically different brain is… Well, it’s an unreliable indicator, because technically the cells will have DNA and that DNA will usually (but not always; there are other options) have XX or XY chromosomes, which will usually (but again, not always) match apparent sex (in about 1/2000 cases there’s a mismatch, which is more common than, say, red hair; sometimes people find out about a chromosomal mismatch only later in life when getting a DNA test for some unrelated reason), and in any case, even for most of us, the chromosomal differences don’t count for much outside of antenatal development (telling the default genital materials which genitals to develop into, though this too can get diverted, per many intersex possibilities, which is also a lot more common than people think) or chromosome-specific conditions like colorblindness…

The notion of a hormonally different brain is, in contrast to all of the above, a reliable and easily verifiable thing.

See for example:

Alzheimer’s Sex Differences May Not Be What They Appear

Dr. Gottfried urges us to take the above seriously!

Because, if women get Alzheimer’s much more commonly than men, and the disease progresses much more quickly in women than men, but that’s based on postmenopausal women not on HRT, then that’s saying “Women, without women’s usual hormones, don’t do so well as men with men’s usual hormones”.

She does, by the way, advocate for bioidentical HRT for menopausal women, unless contraindicated for some important reason that your doctor/endocrinologist knows about. See also:

Menopausal HRT: A Tale Of Two Approaches (Bioidentical vs Animal)

The other very relevant hormone

…that Dr. Gottfried wants us to pay attention to is insulin.

Or rather, its scrubbing enzyme, the prosaically-named “insulin-degrading enzyme”, but it doesn’t only scrub insulin. It also scrubs amyloid beta—yes, the same that produces the amyloid beta plaques in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s. And, there’s only so much insulin-degrading enzyme to go around, and if it’s all busy breaking down excess insulin, there’s not enough left to do the other job too, and thus can’t break down amyloid beta.

In other words: to fight neurodegeneration, keep your blood sugars healthy.

This may actually work by multiple mechanisms besides the amyloid hypothesis, by the way:

The Surprising Link Between Type 2 Diabetes & Alzheimer’s

Want more from Dr. Gottfried?

You might like this interview with Dr. Gottfried by Dr. Benson at the IMCJ:

Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal | Conversations with Sara Gottfried, MD

…in which she discusses some of the things we talked about today, and also about her shift from a pharmaceutical-heavy approach to a predominantly lifestyle medicine approach.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Black Beans vs Fava Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing black beans to fava beans, we picked the black beans.

Why?

In terms of macros, black beans have more protein, carbs, and notably more fiber, the ratio of the latter two also being such that black beans enjoy the lower glycemic index (but both are still good). All in all, a clear win for black beans in this category.

In the category of vitamins, black beans have more of vitamins B1, B5, B6, E, K, and choline, while fava beans have more of vitamins A, B2, B3, B9, and C. That’s a marginal 6:5 win for black beans, before we take into account that they also have 43x as much vitamin E, which is quite a margin, while fava beans doesn’t have any similarly stand-out nutrient. So, another clear win for black beans.

When it comes to minerals, black beans have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium, while fava beans have more manganese, selenium, and zinc. Superficially this is a 6:3 win for black beans; it’s worth noting however that the margins aren’t high on either side in the case of any mineral, so this one’s closer than it looks. Still a win for black beans, though.

Adding up the sections makes for an easy overall win for black beans, but by all means, enjoy either or both—diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Vit D + Calcium: Too Much Of A Good Thing?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Vit D + Calcium: Too Much Of A Good Thing?

- Myth: you can’t get too much calcium!

- Myth: you must get as much vitamin D as possible!

Let’s tackle calcium first:

❝Calcium is good for you! You need more calcium for your bones! Be careful you don’t get calcium-deficient!❞

Contingently, those comments seem reasonable. Contingently on you not already having the right amount of calcium. Most people know what happens in the case of too little calcium: brittle bones, osteoporosis, and so forth.

But what about too much?

Hypercalcemia

Having too much calcium—or “hypercalcemia”— can lead to problems with…

- Groans: gastrointestinal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Peptic ulcer disease and pancreatitis.

- Bones: bone-related pains. Osteoporosis, osteomalacia, arthritis and pathological fractures.

- Stones: kidney stones causing pain.

- Moans: refers to fatigue and malaise.

- Thrones: polyuria, polydipsia, and constipation

- Psychic overtones: lethargy, confusion, depression, and memory loss.

(mnemonic courtesy of Sadiq et al, 2022)

What causes this, and how do we avoid it? Is it just dietary?

It’s mostly not dietary!

Overconsumption of calcium is certainly possible, but not common unless one has an extreme diet and/or over-supplementation. However…

Too much vitamin D

Again with “too much of a good thing”! While keeping good levels of vitamin D is, obviously, good, overdoing it (including commonly prescribed super-therapeutic doses of vitamin D) can lead to hypercalcemia.

This happens because vitamin D triggers calcium absorption into the gut, and acts as gatekeeper to the bloodstream.

Normally, the body only absorbs 10–20% of the calcium we consume, and that’s all well and good. But with overly high vitamin D levels, the other 80–90% can be waved on through, and that is very much Not Good™.

See for yourself:

- Hypercalcemia of Malignancy: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management

- Vitamin D-Mediated Hypercalcemia: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

How much is too much?

The United States’ Office of Dietary Supplements defines 4000 IU (100μg) as a high daily dose of vitamin D, and recommends 600 IU (15μg) as a daily dose, or 800 IU (20μg) if aged over 70.

See for yourself: Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals ← there’s quite a bit of extra info there too

Share This Post

-

Coenzyme Q10 From Foods & Supplements

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Coenzyme Q10 and the difference it makes

Coenzyme Q10, often abbreviated to CoQ10, is a popular supplement, and is often one of the more expensive supplements that’s commonly found on supermarket shelves as opposed to having to go to more specialist stores or looking online.

What is it?

It’s a compound naturally made in the human body and stored in mitochondria. Now, everyone remembers the main job of mitochondria (producing energy), but they also protect cells from oxidative stress, among other things. In other words, aging.

Like many things, CoQ10 production slows as we age. So after a certain age, often around 45 but lifestyle factors can push it either way, it can start to make sense to supplement.

Does it work?

The short answer is “yes”, though we’ll do a quick breakdown of some main benefits, and studies for such, before moving on.

First, do bear in mind that CoQ10 comes in two main forms, ubiquinol and ubiquinone.

Ubiquinol is much more easily-used by the body, so that’s the one you want. Here be science:

What is it good for?

Benefits include:

- Against aging

- Against skin cancer

- Against breast cancer

- Against prostate cancer

- Against heart failure

- Against obesity

- Against diabetes

- Against Alzheimer’s

- Against Parkinson’s

Can we get it from foods?

Yes, and it’s equally well-absorbed through foods or supplementation, so feel free to go with whichever is more convenient for you.

Read: Intestinal absorption of coenzyme Q10 administered in a meal or as capsules to healthy subjects

If you do want to get it from food, you can get it from many places:

- Organ meats: the top source, though many don’t want to eat them, either because they don’t like them or some of us just don’t eat meat. If you do, though, top choices include the heart, liver, and kidneys.

- Fatty fish: sardines are up top, along with mackerel, herring, and trout

- Vegetables: leafy greens, and cruciferous vegetables e.g. cauliflower, broccoli, sprouts

- Legumes: for example soy, lentils, peanuts

- Nuts and seeds: pistachios come up top; sesame seeds are great too

- Fruit: strawberries come up top; oranges are great too

If supplementing, how much is good?

Most studies have used doses in the 100mg–200mg (per day) range.

However, it’s also been found to be safe at 1200mg (per day), for example in this high-quality study that found that higher doses resulted in greater benefit, in patients with early Parkinson’s Disease:

Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: evidence of slowing of the functional decline

Wondering where you can get it?

We don’t sell it (or anything else for that matter), and you can probably find it in your local supermarket or health food store. However, if you’d like to buy it online, here’s an example product on Amazon

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

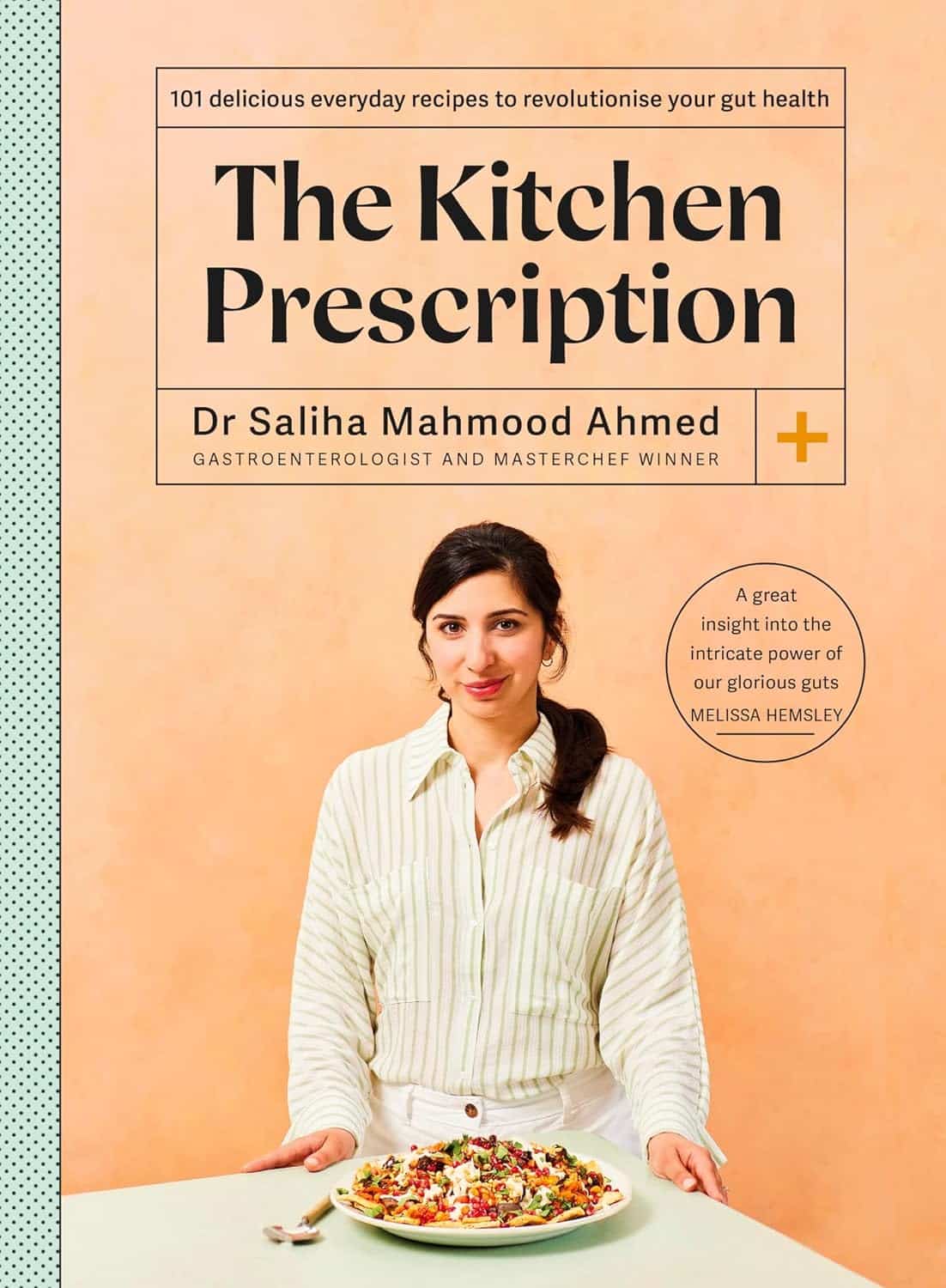

The Kitchen Prescription – by Saliha Mahmood Ahmed

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One of the biggest challenges facing anyone learning to cook more healthily, is keeping it tasty. What to cook when your biggest comfort foods all contain things you “should” avoid?

Happily for us, Dr. Ahmed is here with a focus on comfort food that’s good for your gut health. It’s incidentally equally good for the heart and good against diabetes… but Dr. Ahmed is a gastroenterologist, so that’s where she’s coming from with these.

There’s a wide range of 101 recipes here, including many tagged vegetarian, vegan, and/or gluten-free, as appropriate.

While this is not a vegetarian cookbook, Dr. Ahmed does consider the key components of a good diet to be, in order of quantity that should be consumed:

- Fruits and vegetables

- Whole grains

- Legumes

- Pulses

- Nuts and seeds

…and as such, the recipes are mostly plant-based.

The recipes are from all around the world, and/but the ingredients are mostly things that are almost universal. In the event that something might be hard-to-get, she suggests an appropriate substitution.

The recipes are straightforward and clear, as well as being beautifully illustrated.

All in all, a fine addition to anyone’s kitchen!

Get your copy of The Kitchen Prescription from Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Healing After Loss – by Martha Hickman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mental health is also just health, and this book’s about an underexamined area of mental health. We say “underexamined”, because for something that affects almost everyone sooner or later, there’s not nearly so much science being done about it as other areas of mental health.

This is not a book of science per se, but it is a very useful one. The format is:

Each calendar day of the year, there’s a daily reflection, consisting of:

- A one-liner insight about grief, quoted from somebody

- A page of thoughts about this

- A one-liner summary, often formulated as a piece of advice

The book is not religious in content, though the author does occasionally make reference to God, only in the most abstract way that shouldn’t be offputting to any but the most stridently anti-religious readers.

Bottom line: if this is a subject near to your heart, then you will almost certainly benefit from this daily reader.

Click here to check out Healing After Loss, and indeed heal after loss

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Superfood Baked Apples

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Superfoods, and super-tasty. This is a healthy twist on a classic; your blood sugars will thank you for choosing this tasty sweet delight. It’s also packed with nutrients!

You will need

- 2 large firm baking apples, cored but not peeled

- 1/2 cup chopped walnuts

- 3 tbsp goji berries, rehydrated (soak them in warm water for 10–15minutes and drain)

- 1 tbsp honey, or maple syrup, per your preference (this writer is also a fan of aged balsamic vinegar for its strong flavor and much milder sweetness. If you don’t like things to be too sweet, this is the option for you)

- 2 tsp ground sweet cinnamon

- 1 tsp ground ginger

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 180℃ / 350℉ / gas mark 4

2) Mix the chopped walnuts with the goji berries and the honey (or whatever you used instead of the honey) as well as the sweet cinnamon and the ginger.

3) Place the apples in shallow baking dish, and use the mixture you just made to stuff their holes.

4) Add 1/2 cup water to the dish, around the apples. Cover gently with foil, and bake until soft.

Tip: check them every 20 minutes; they may be done in 40 or it may take 60; in honesty it depends on your oven. If unsure, cook them for longer at a lower temperature.

5) Serve warm.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose C’s

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

- The Sugary Food That Lowers Blood Sugars

- Honey vs Maple Syrup – Which is Healthier?

- A Tale Of Two Cinnamons ← this is important, about why we chose the sweet cinnamon

- Ginger Does A Lot More Than You Think

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: